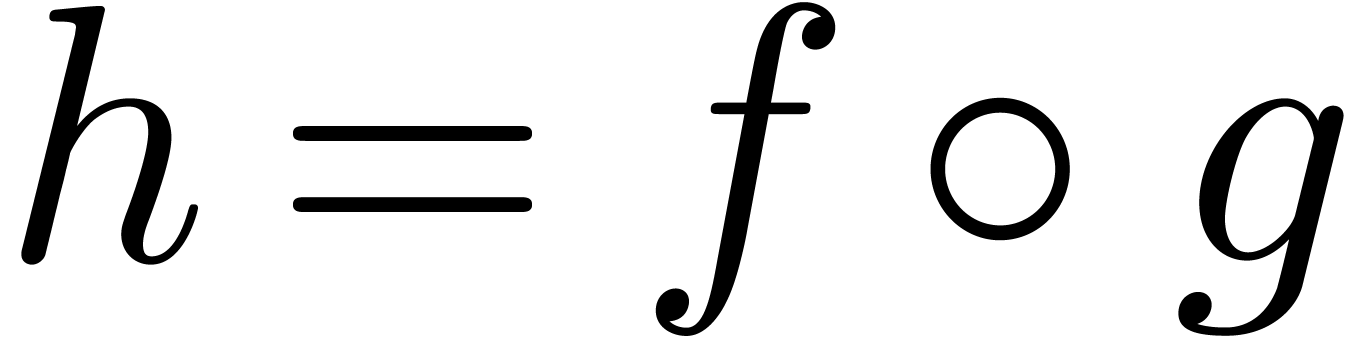

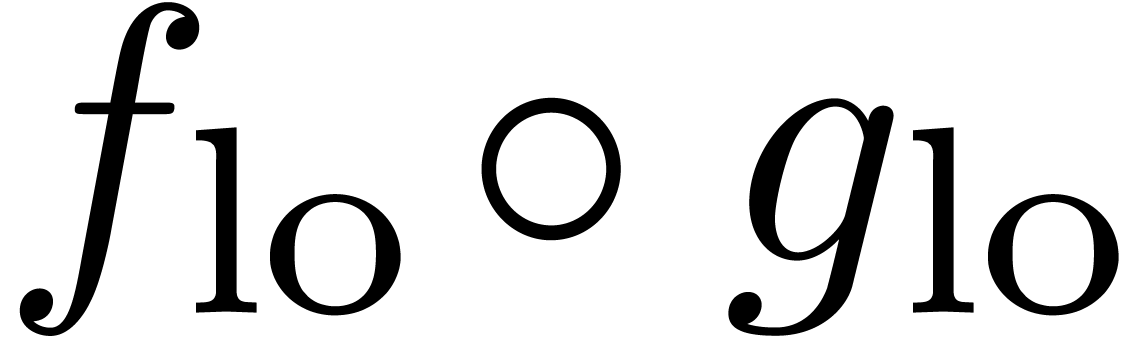

Fast composition of numeric power

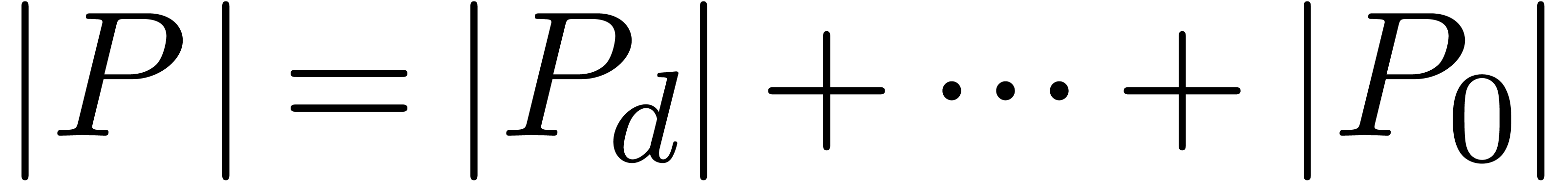

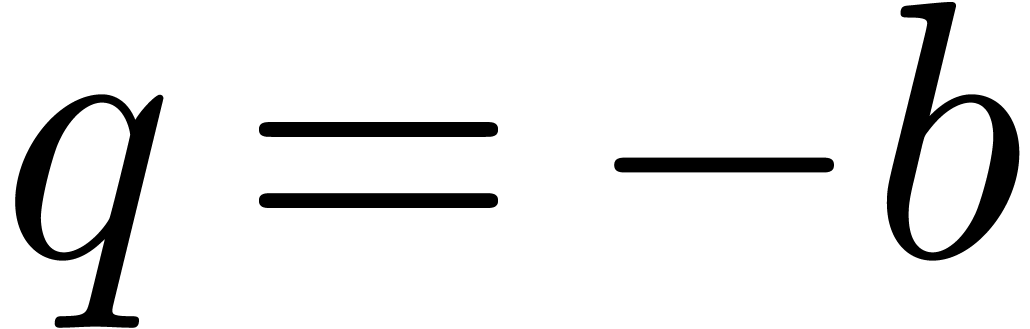

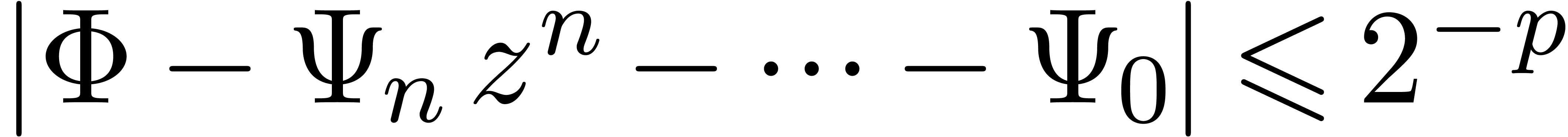

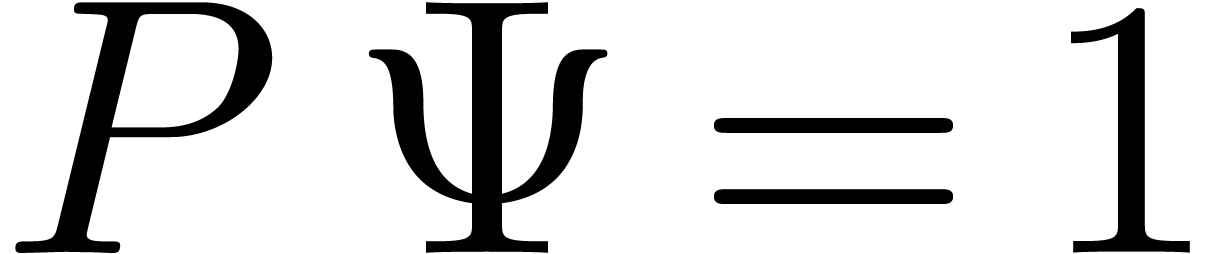

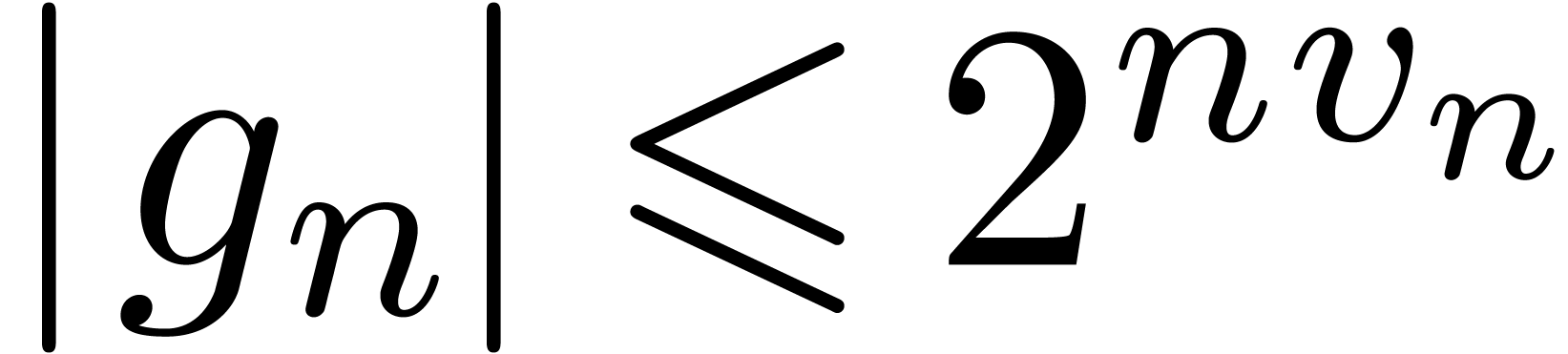

series |

|

| December 9, 2008 |

|

. This work was

partially supported by the ANR Gecko project.

. This work was

partially supported by the ANR Gecko project.

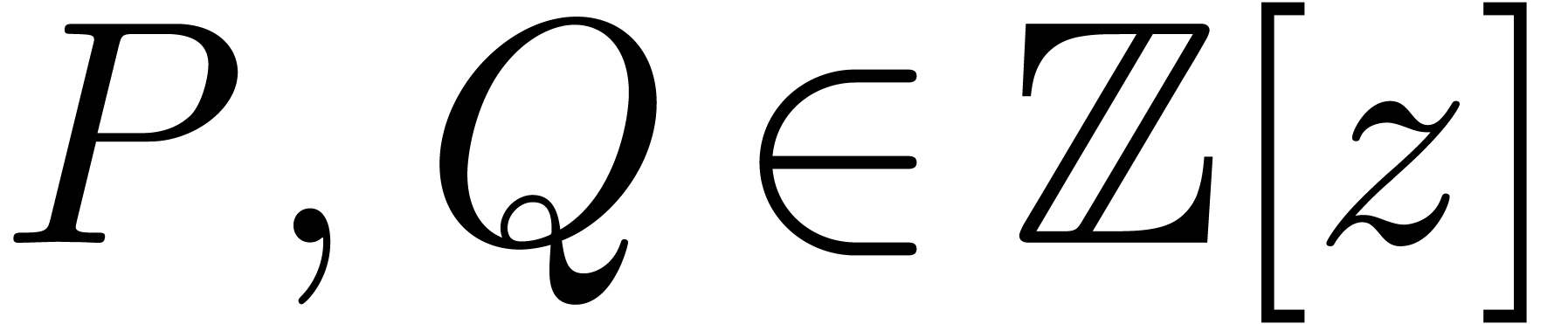

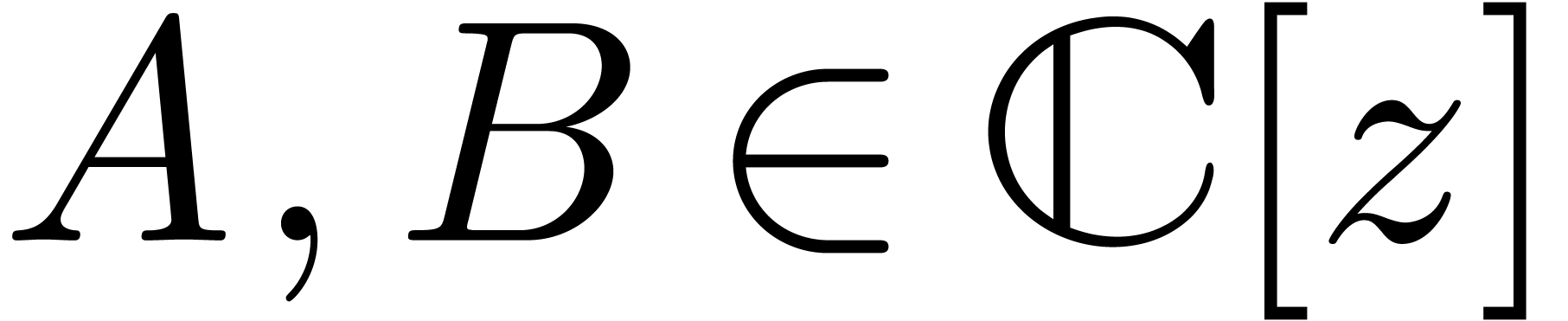

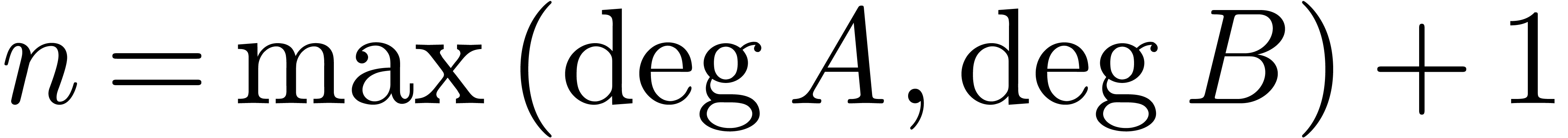

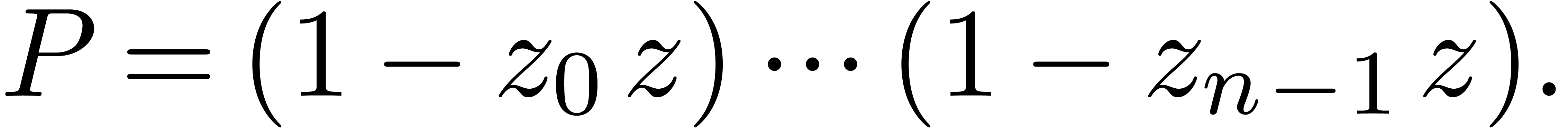

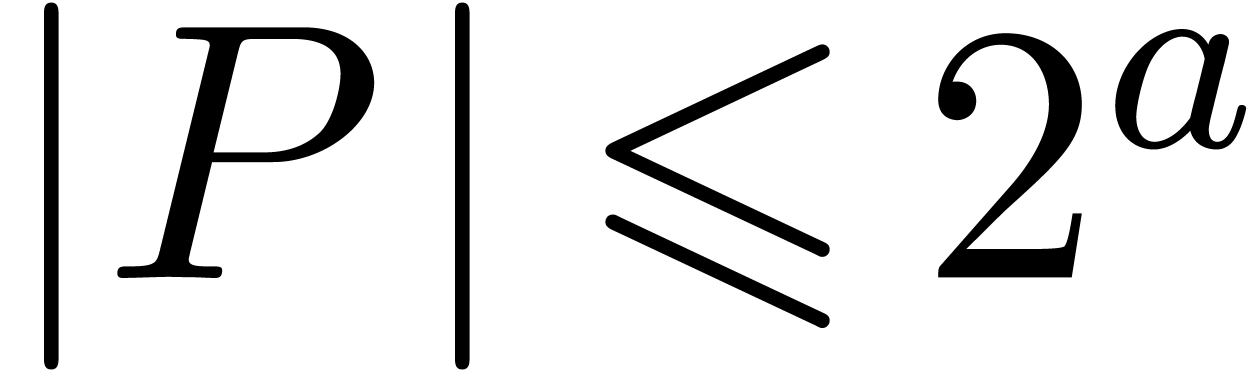

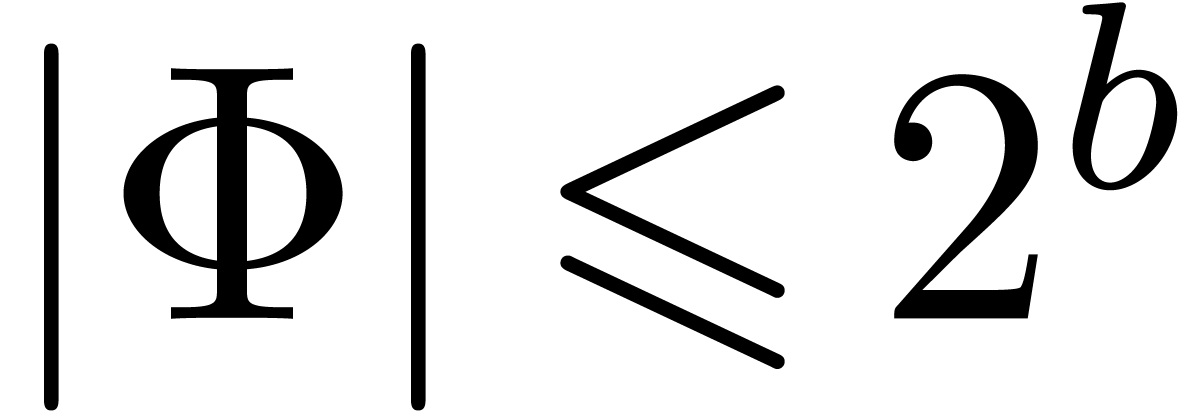

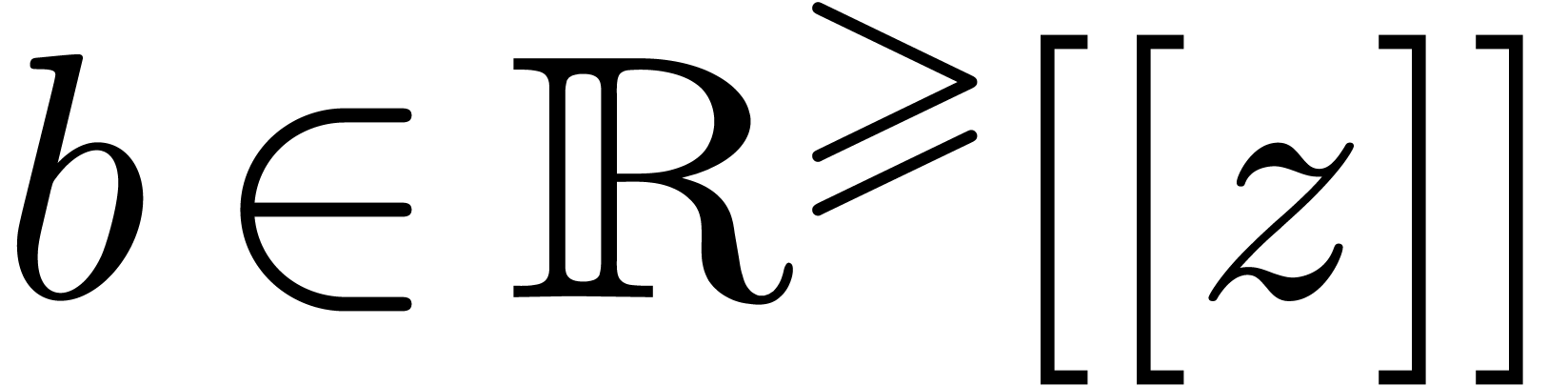

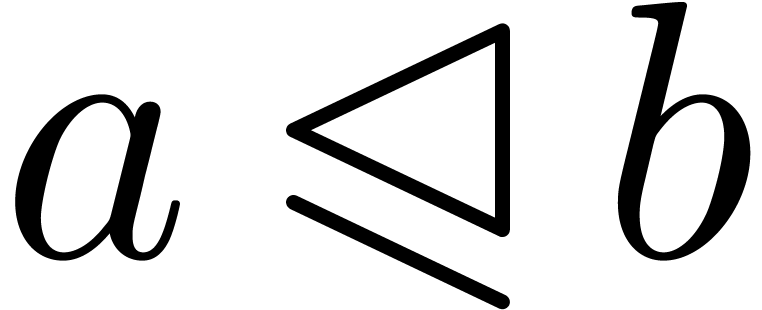

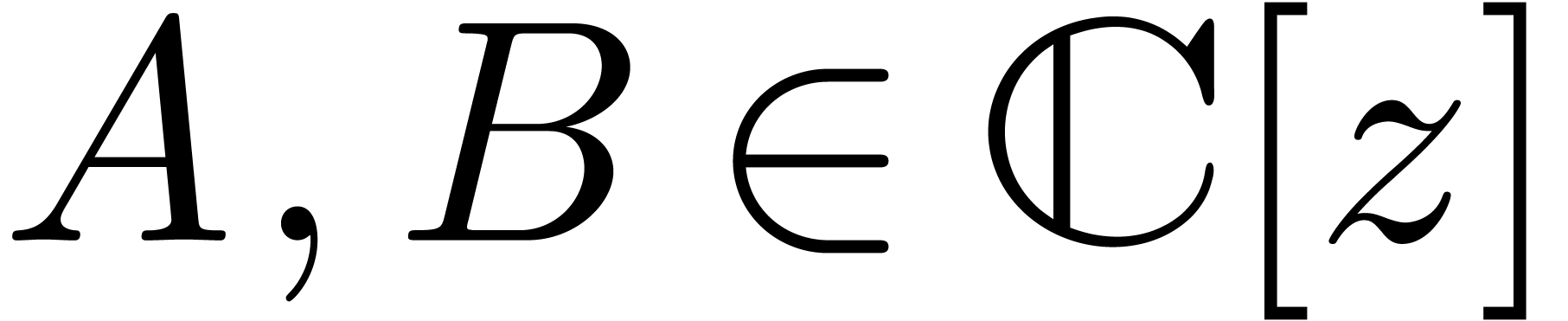

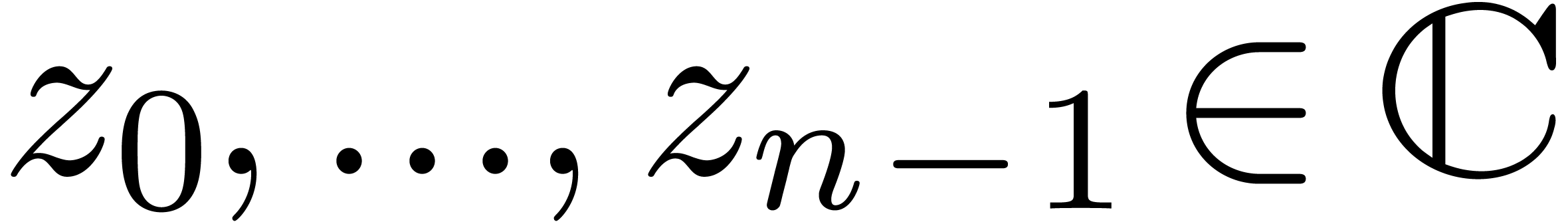

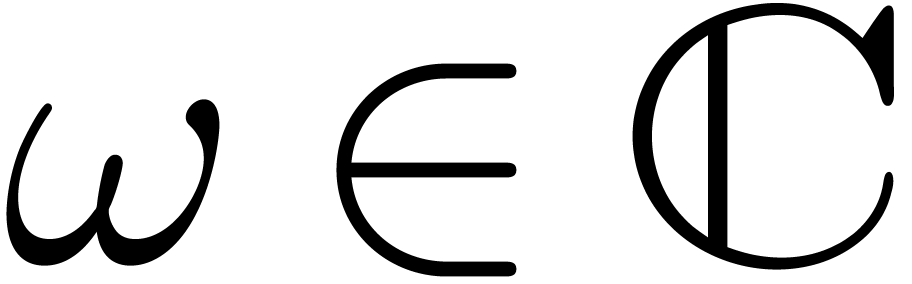

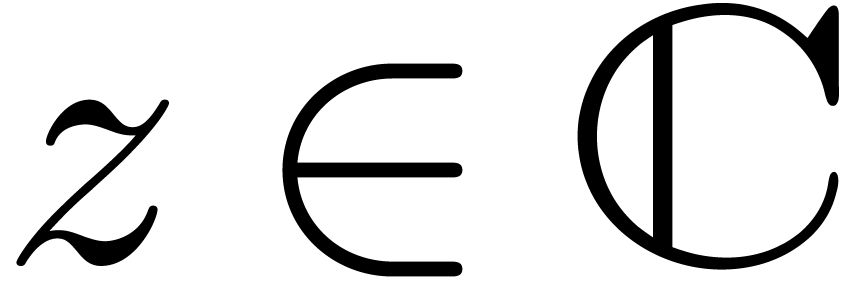

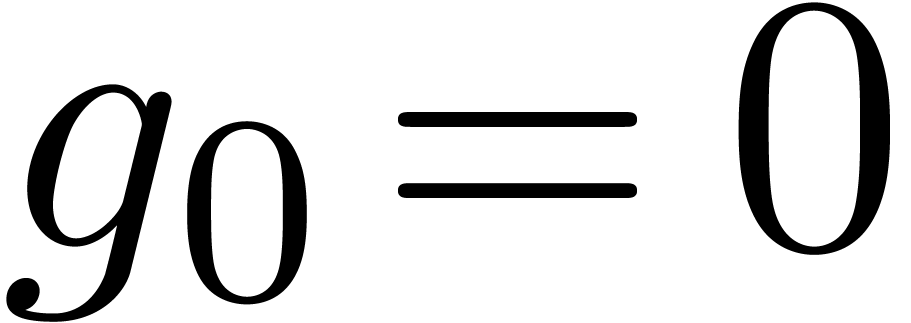

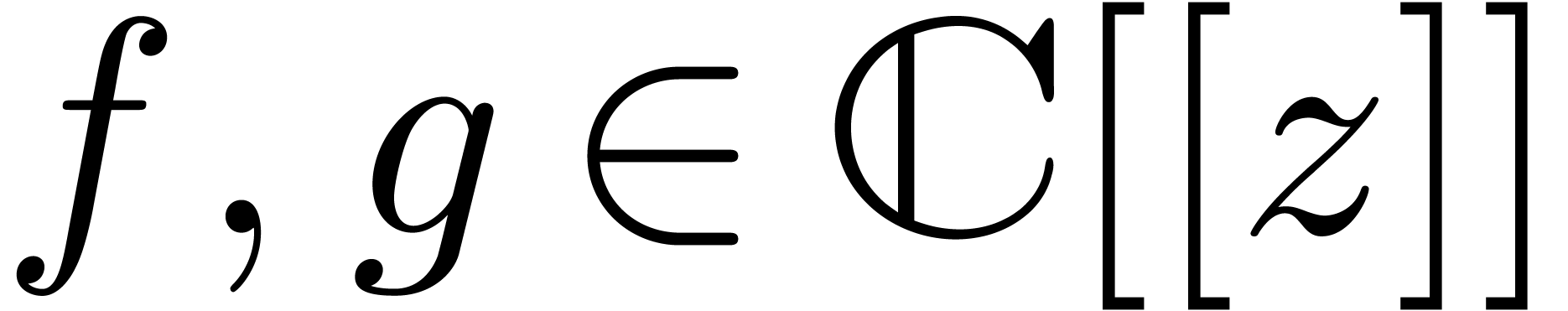

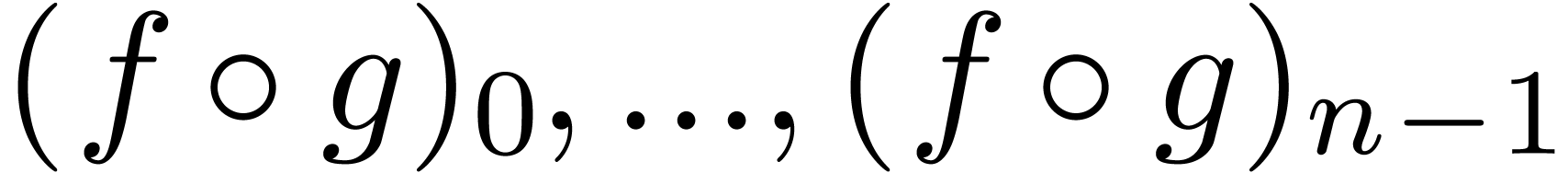

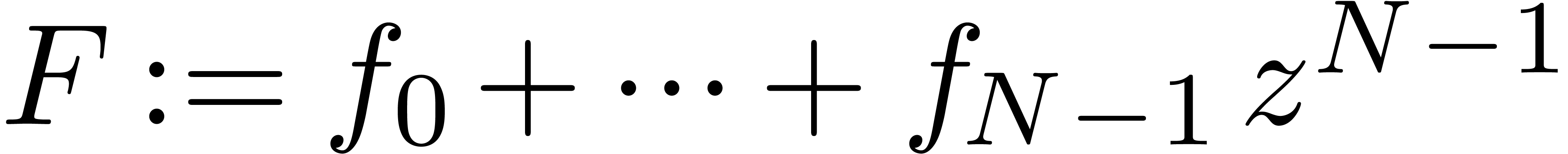

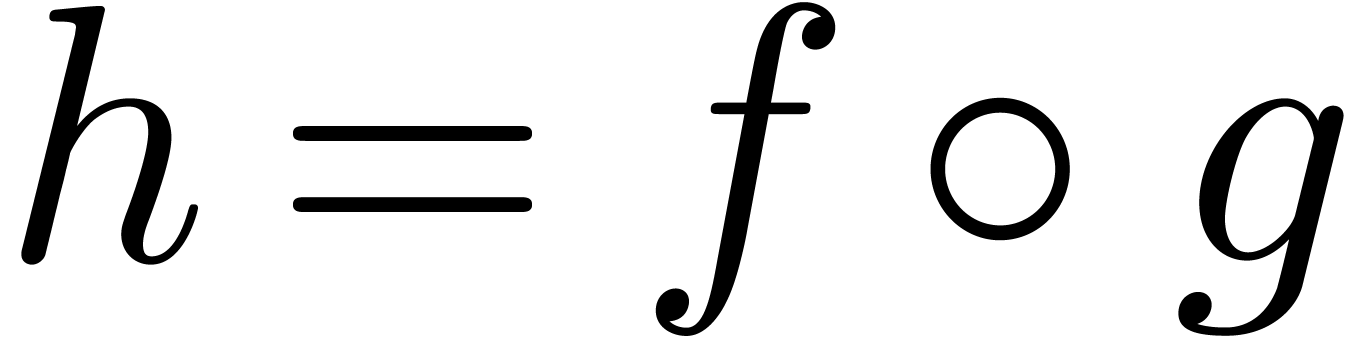

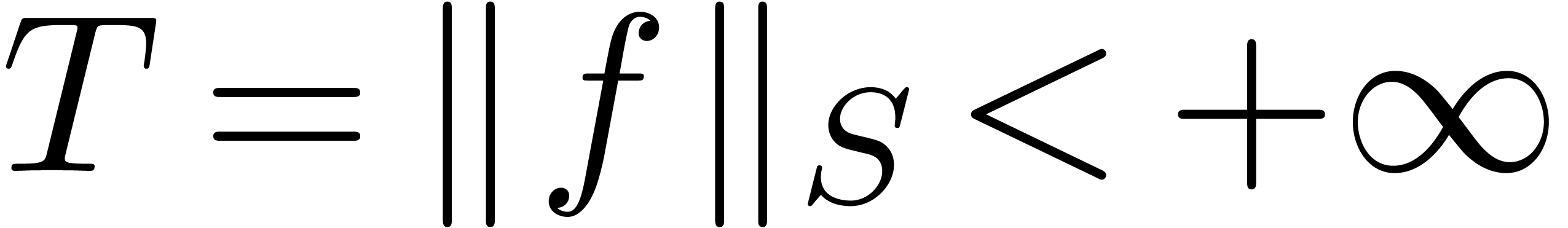

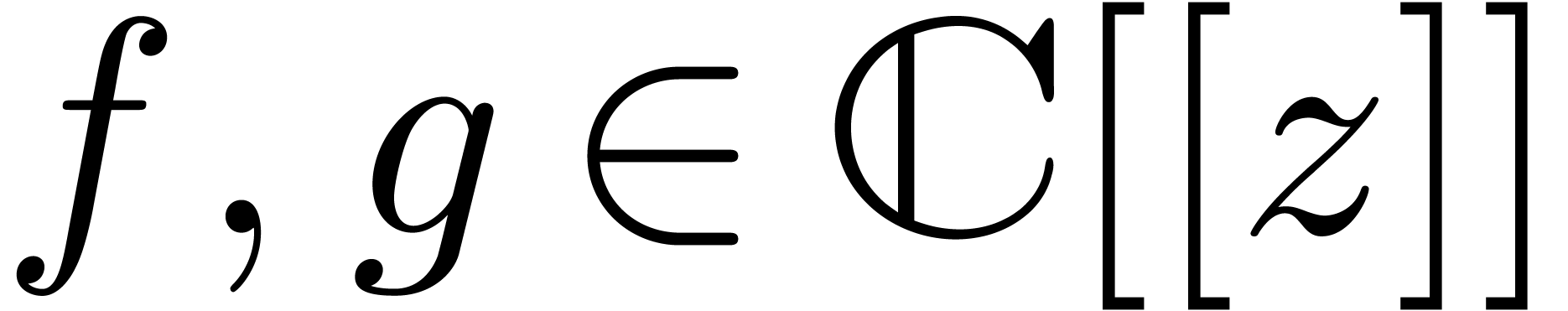

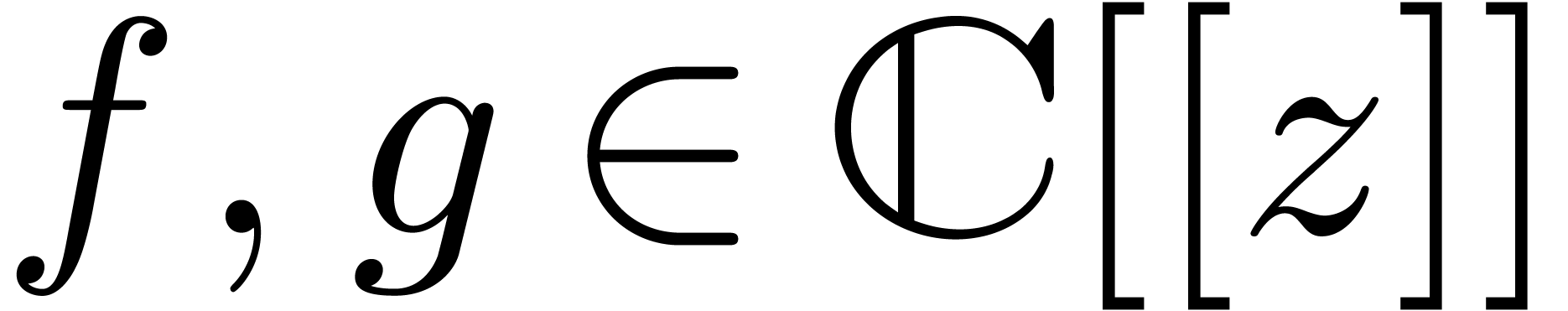

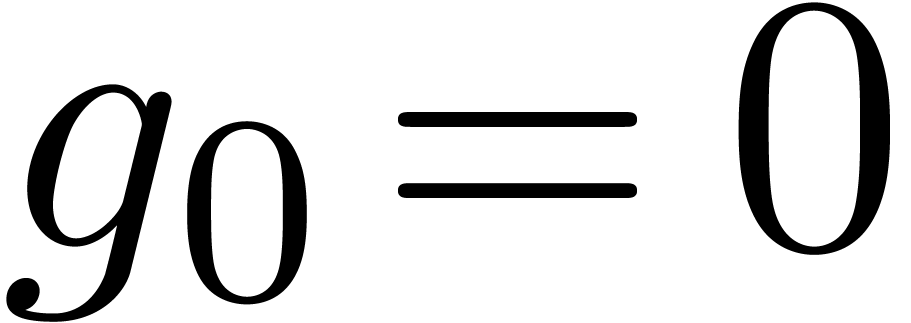

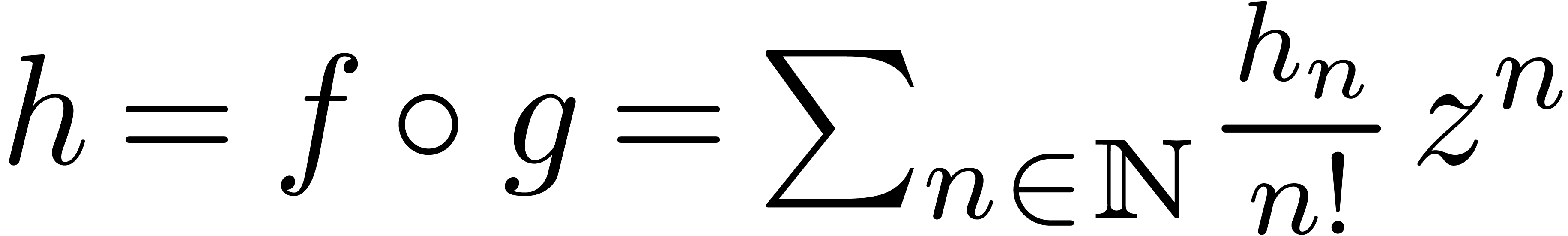

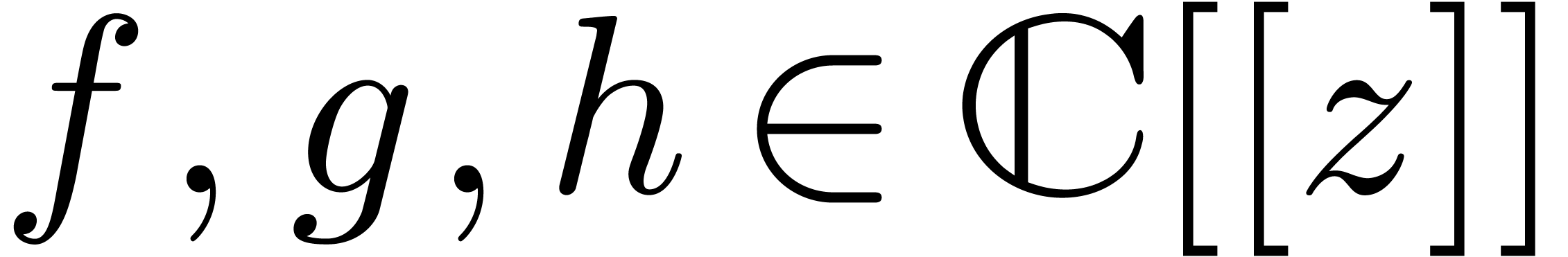

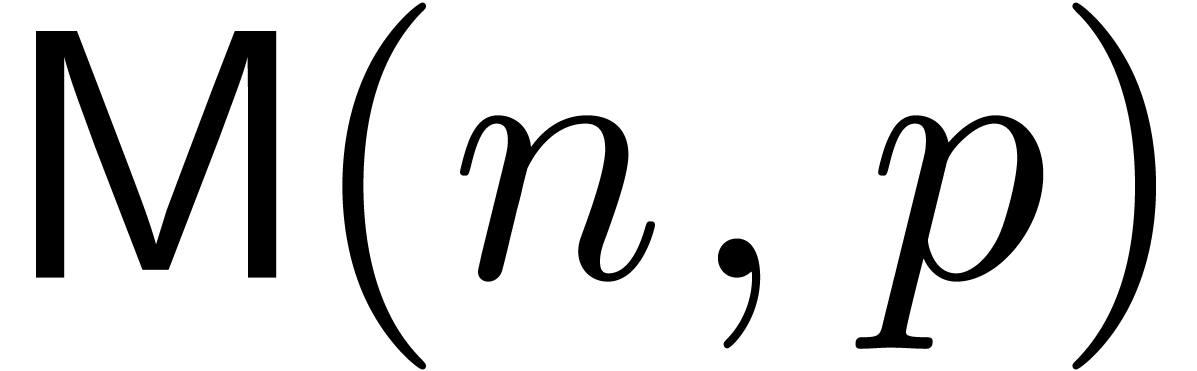

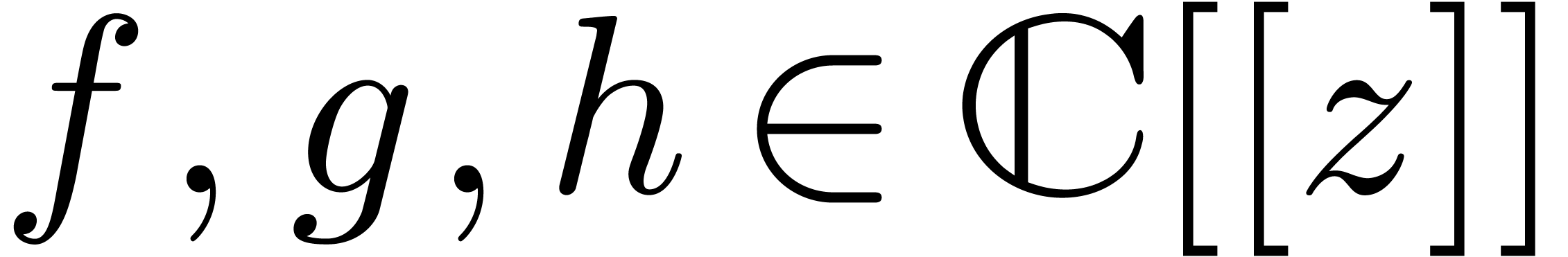

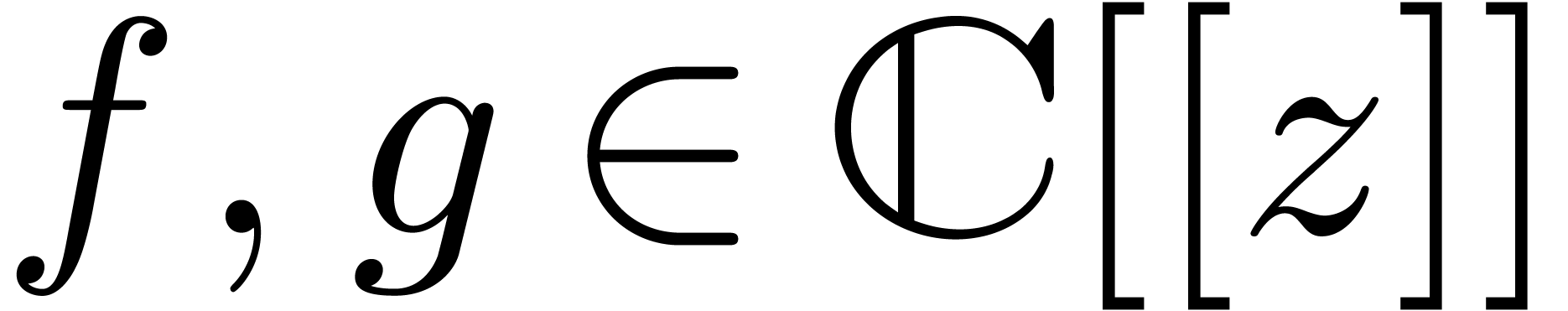

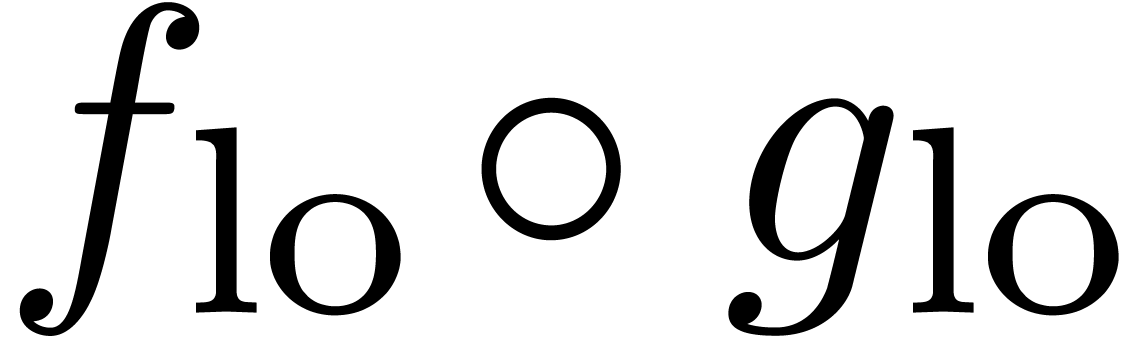

Let

|

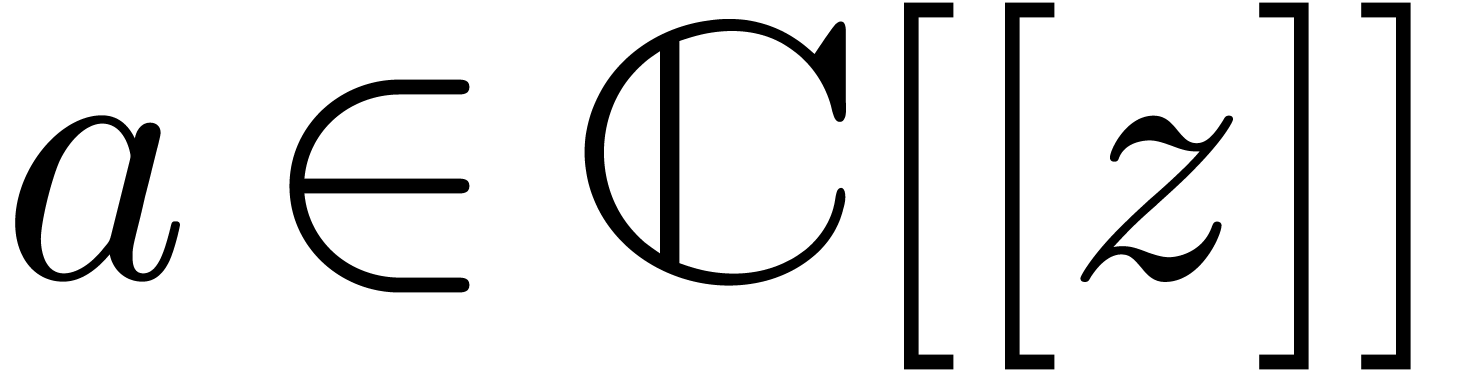

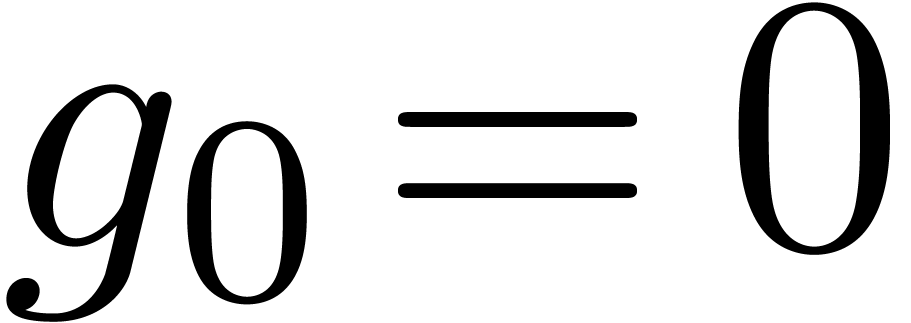

Let  be an effective ring of coefficients

(i.e. we have algorithms for performing the ring

operations). Let

be an effective ring of coefficients

(i.e. we have algorithms for performing the ring

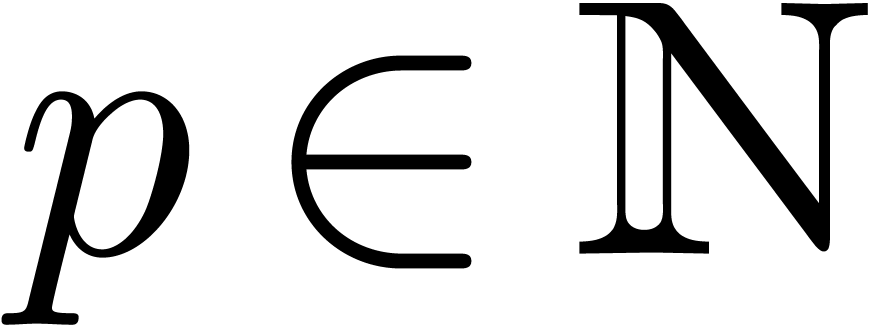

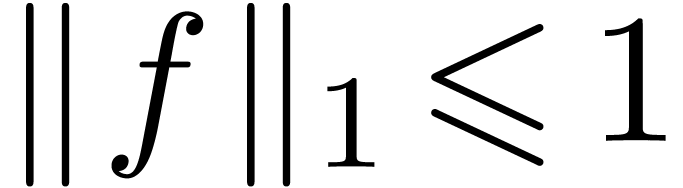

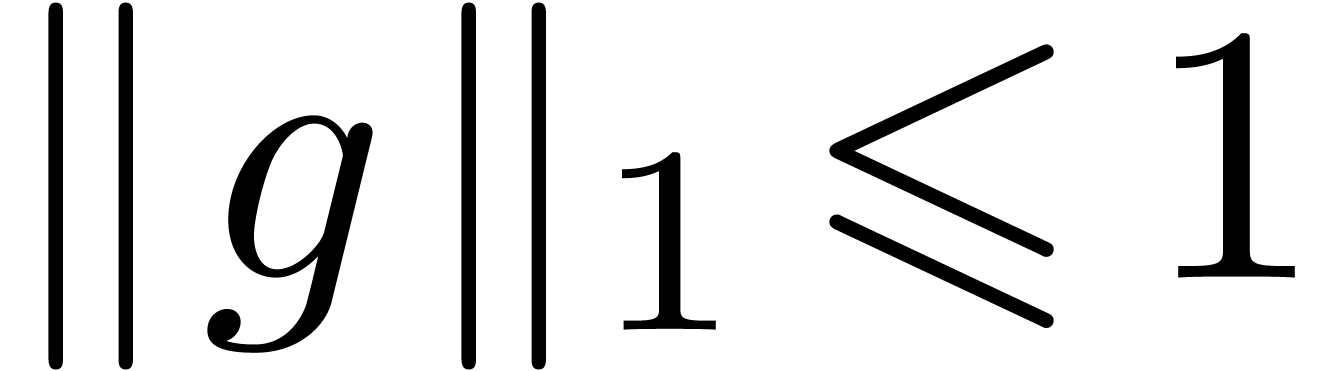

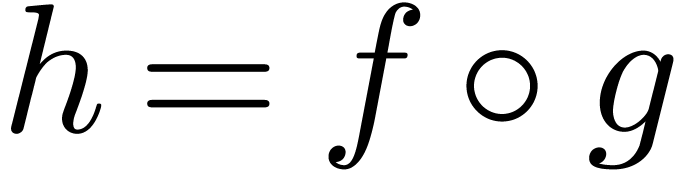

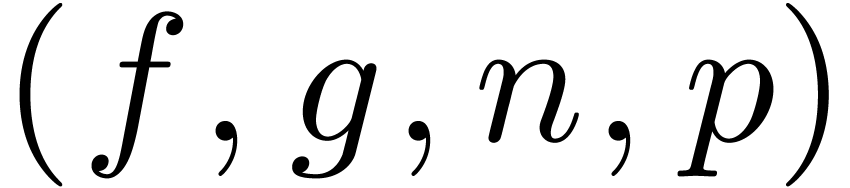

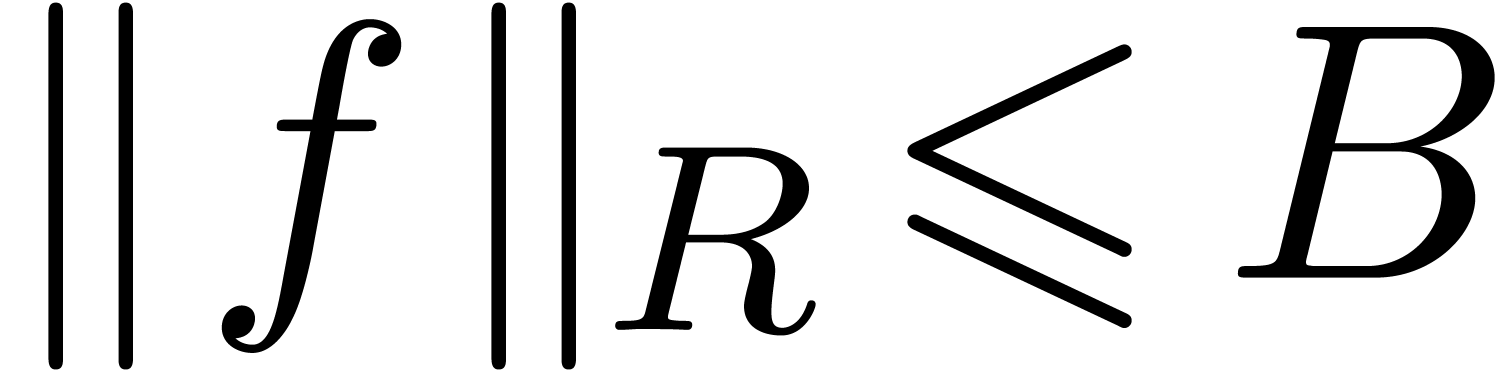

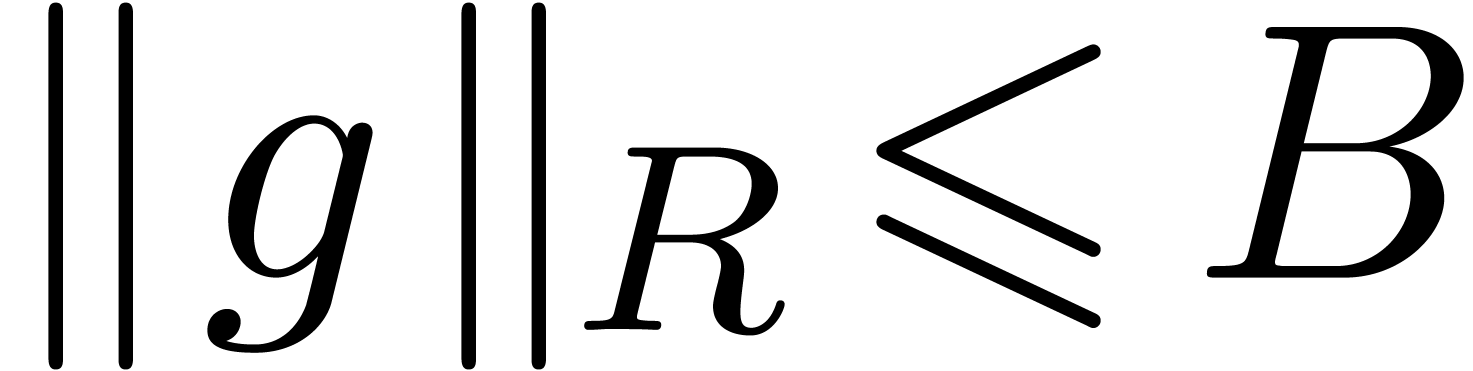

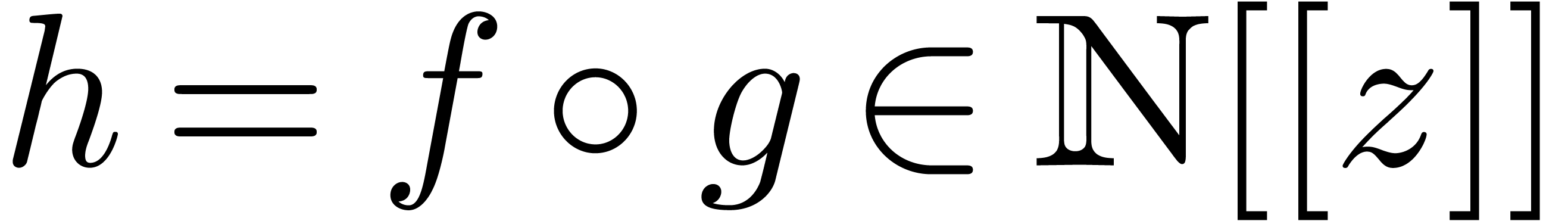

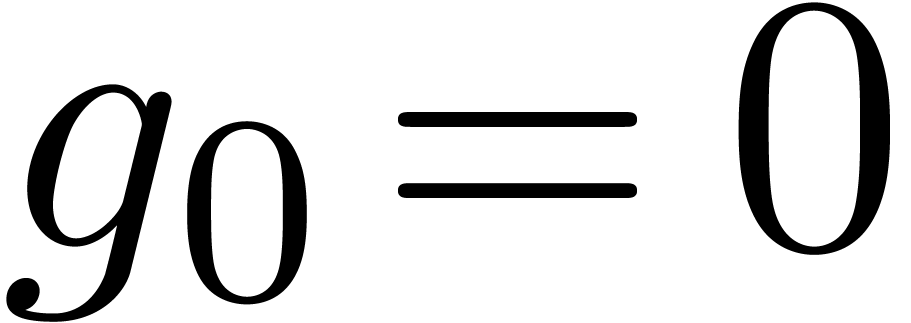

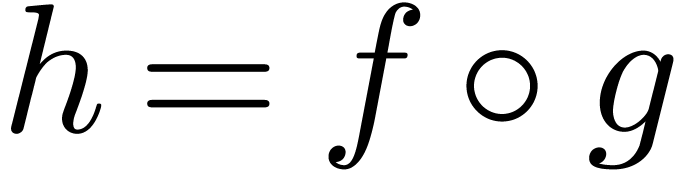

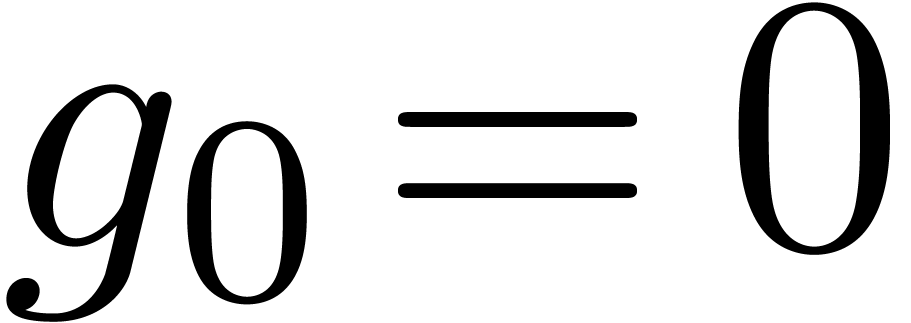

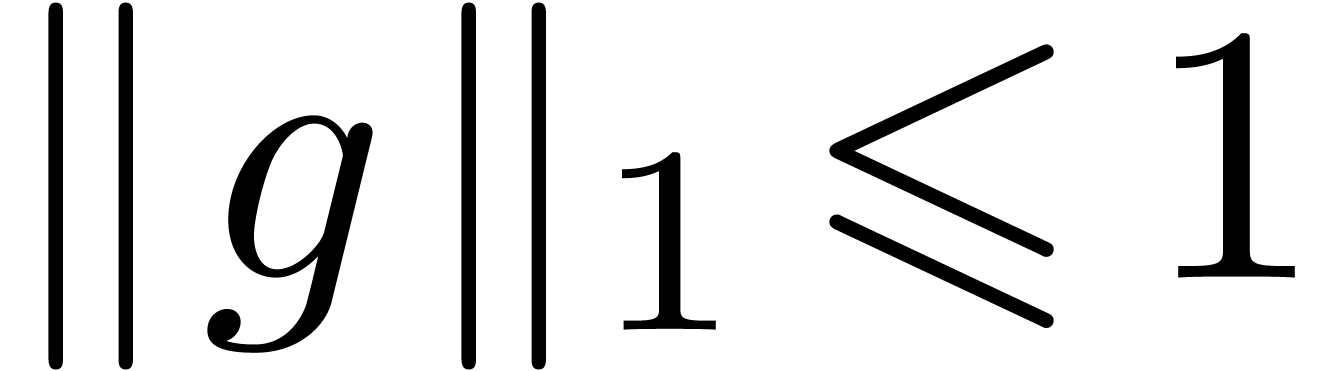

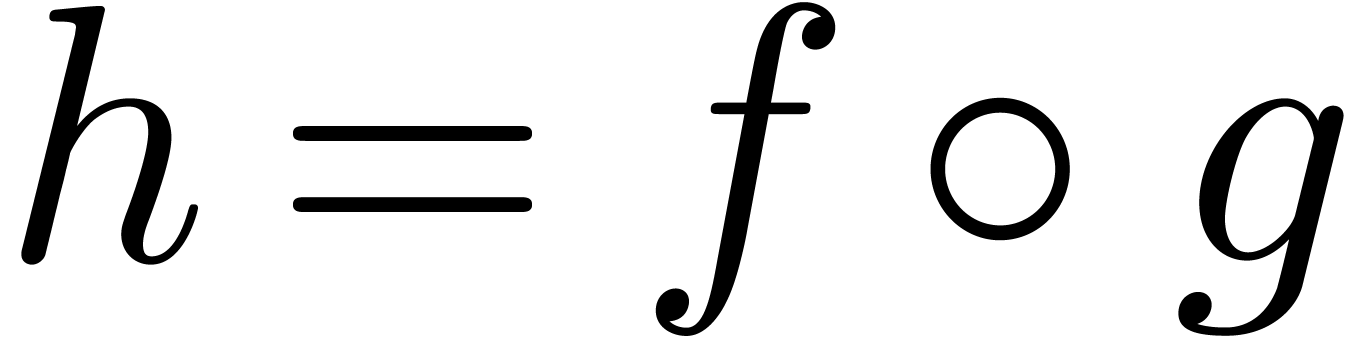

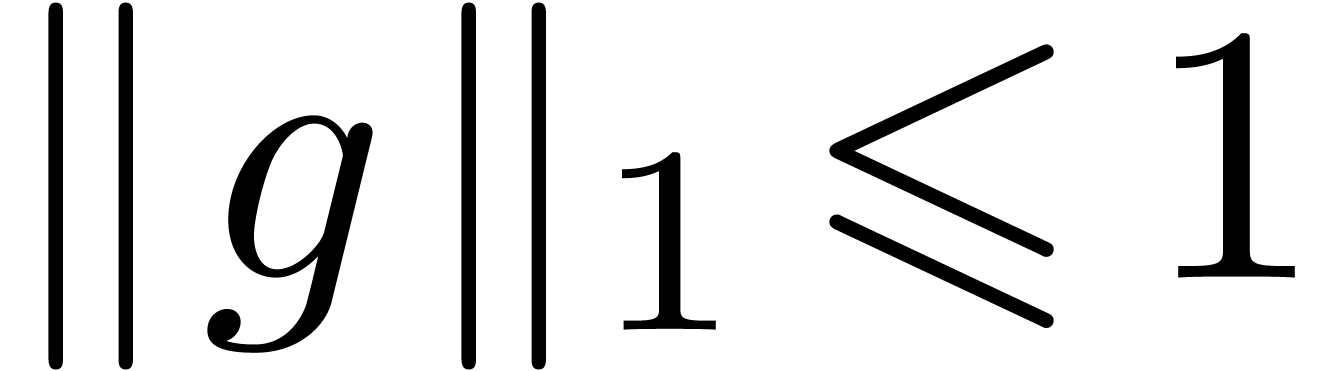

operations). Let  be two power series with

be two power series with  , so that the composition

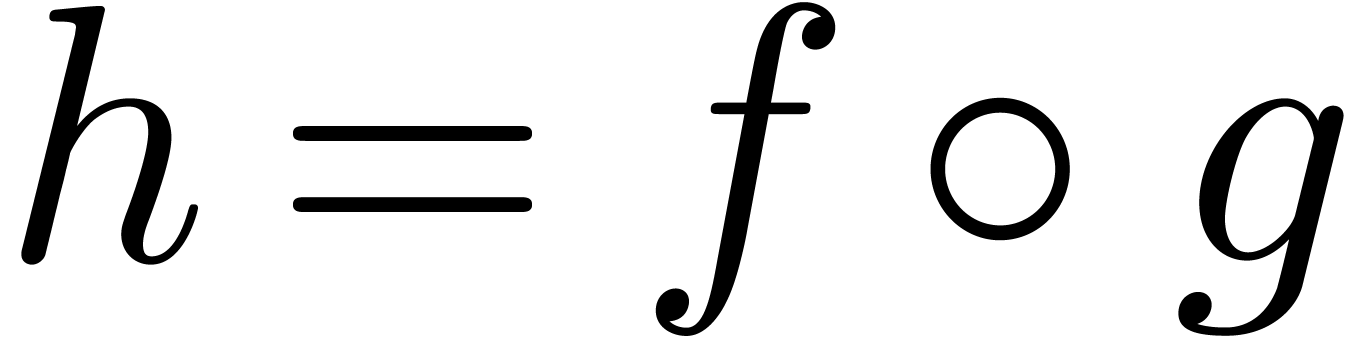

, so that the composition  is well-defined. We are interested in algorithms for fast

composition: given

is well-defined. We are interested in algorithms for fast

composition: given  and

and  , how much arithmetic operations in

, how much arithmetic operations in  are needed in order to compute

are needed in order to compute  ?

?

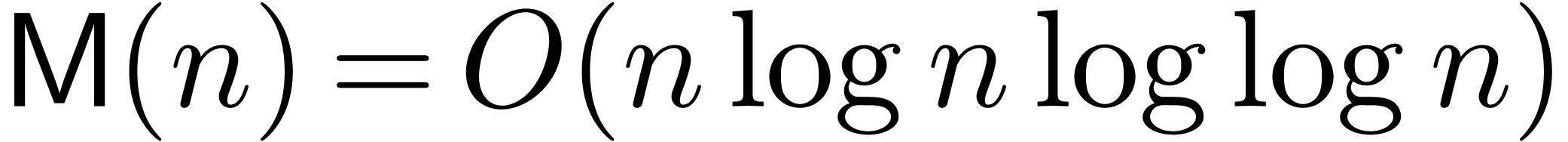

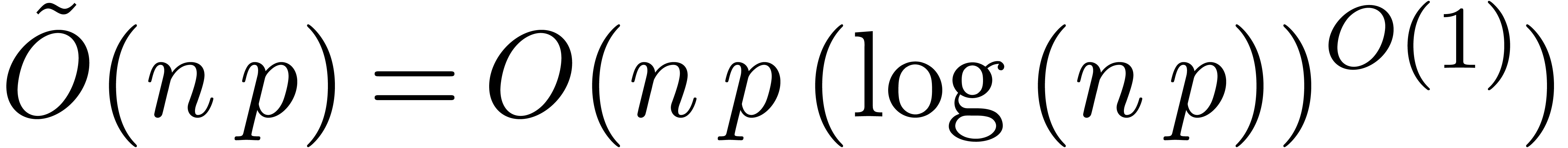

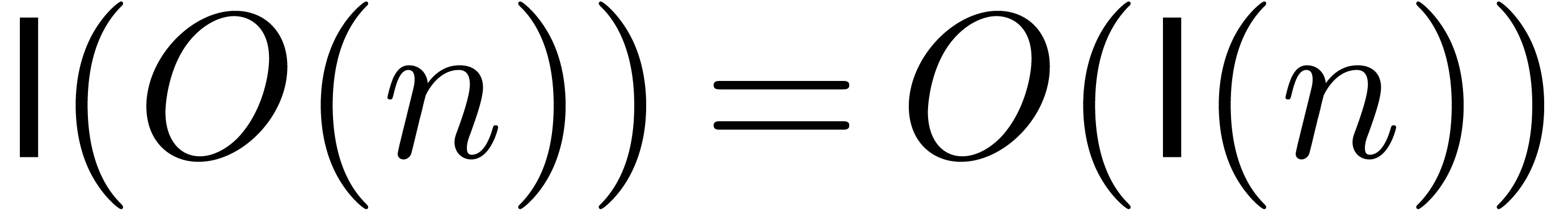

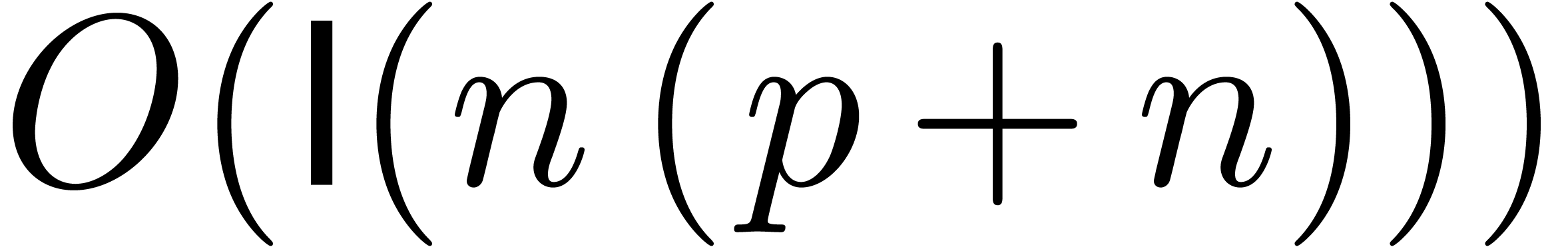

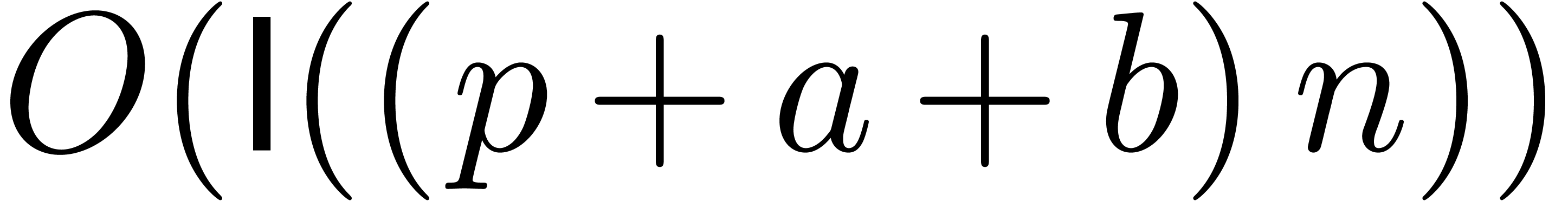

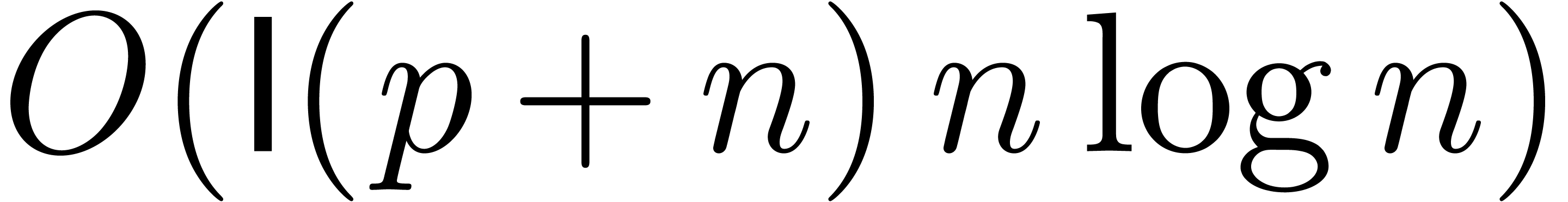

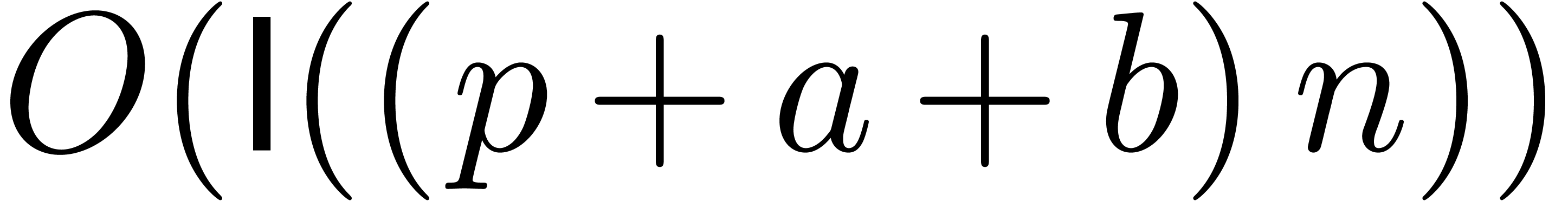

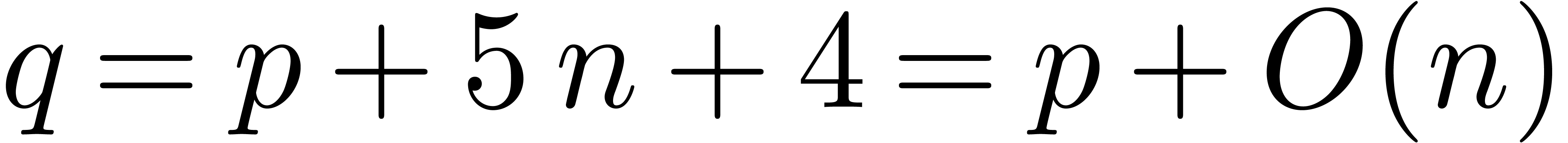

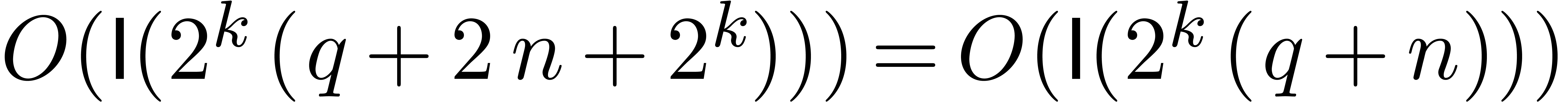

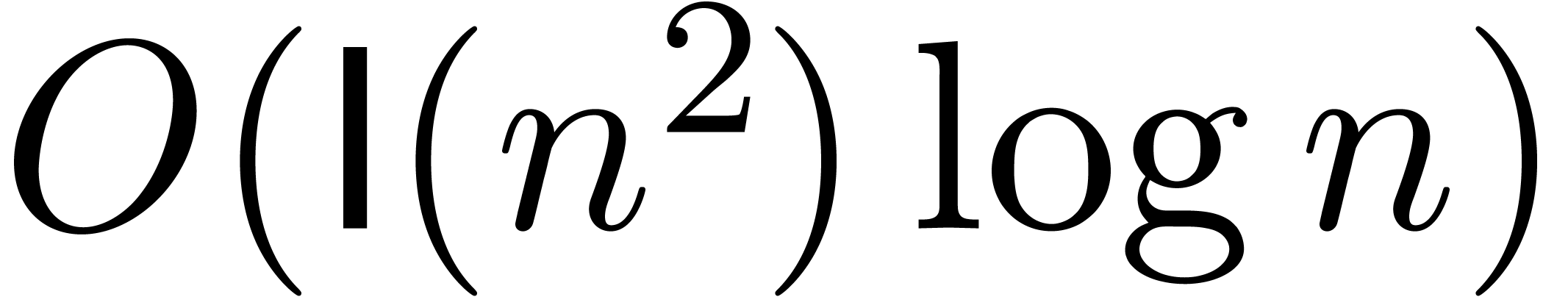

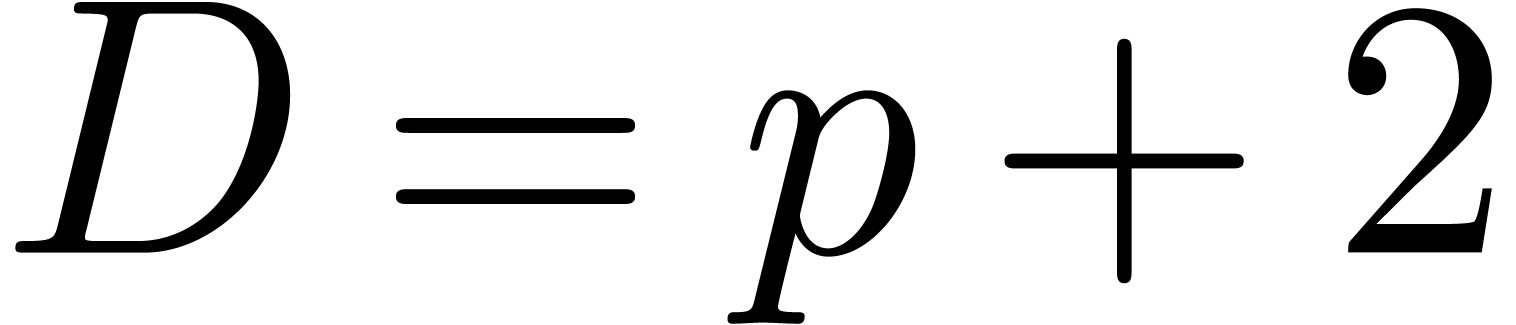

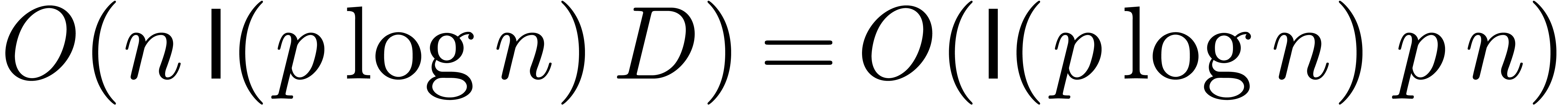

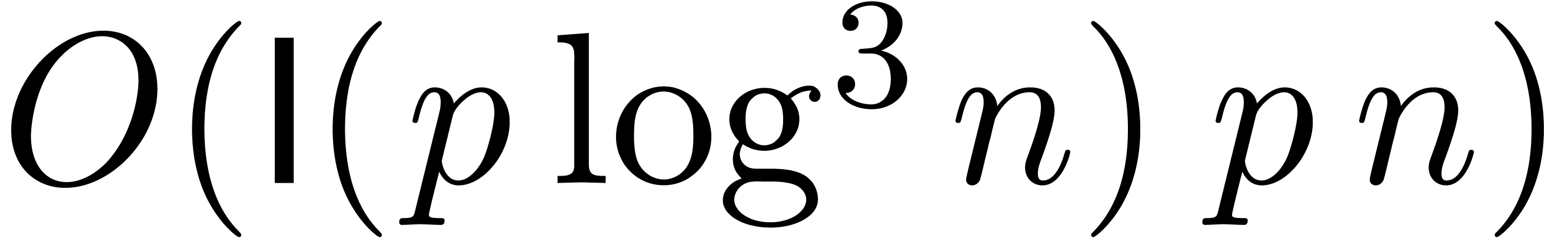

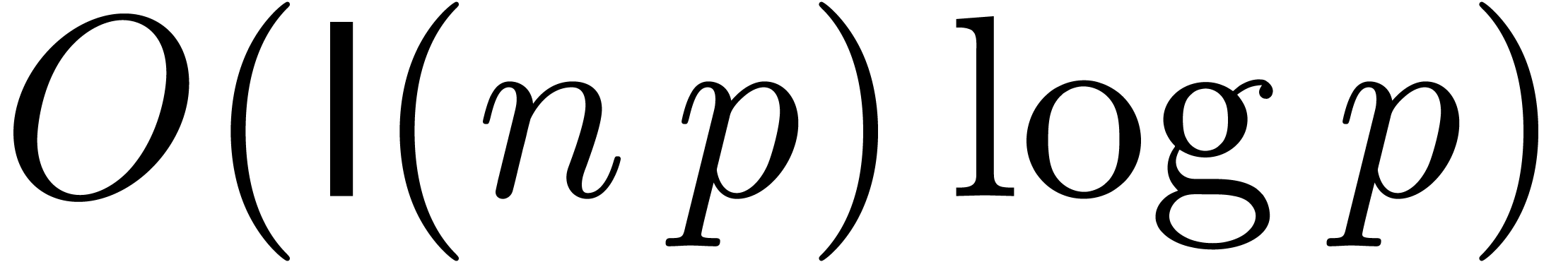

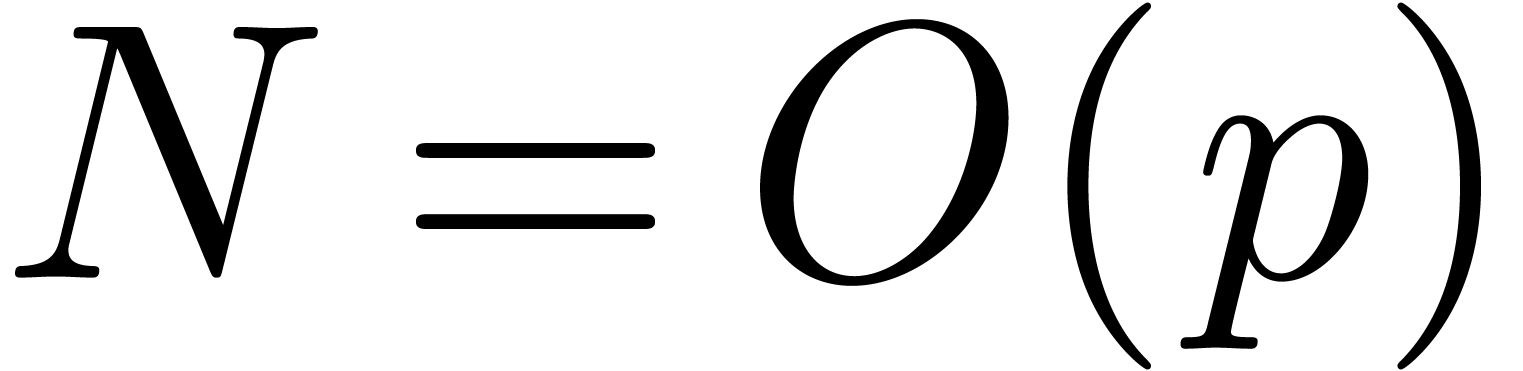

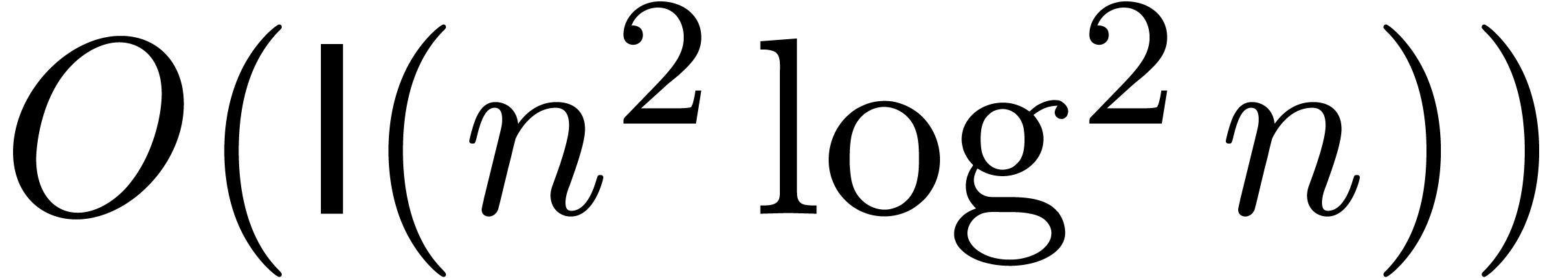

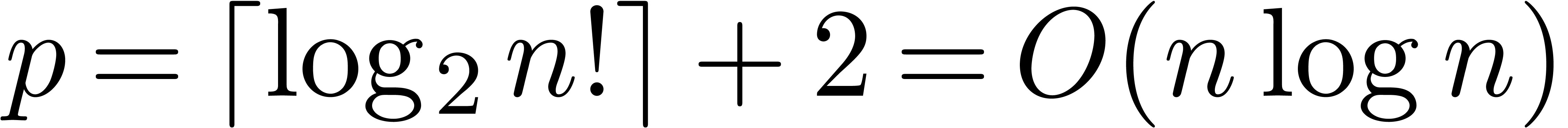

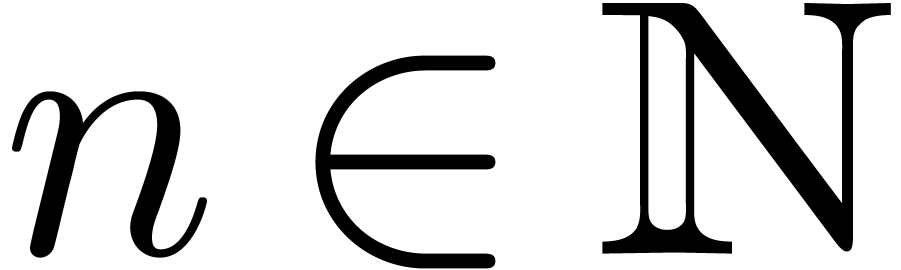

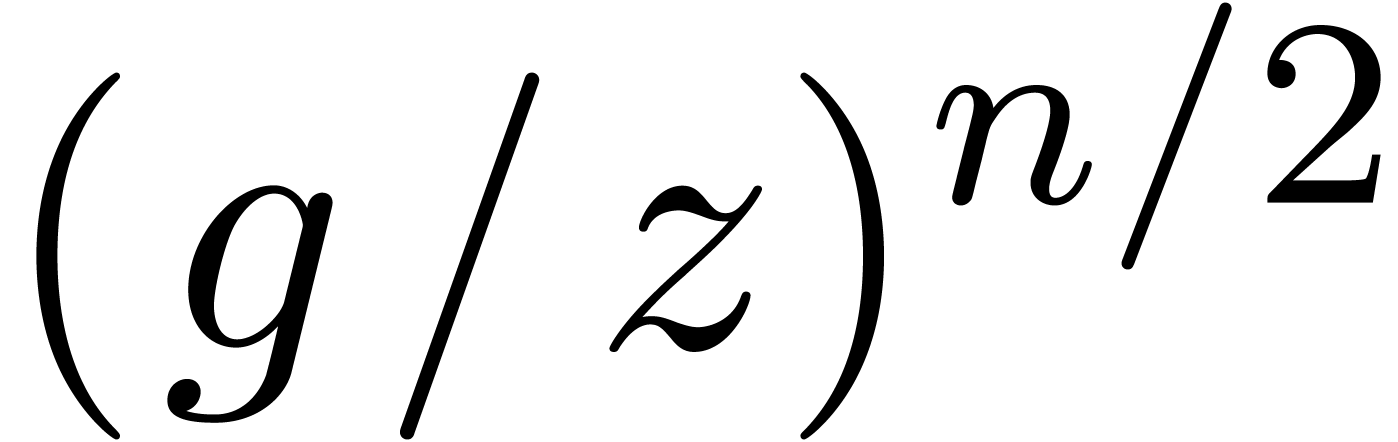

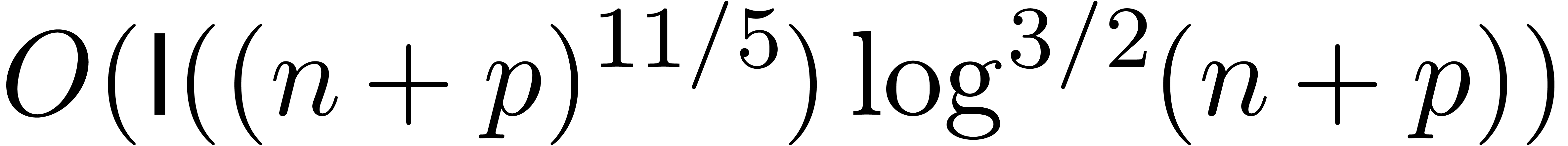

A first efficient general purpose algorithm of time complexity  was given in [BK78, CT65, SS71]. Here

was given in [BK78, CT65, SS71]. Here  denotes the complexity for

the multiplication of two polynomials of degrees

denotes the complexity for

the multiplication of two polynomials of degrees  and we have

and we have  [CK91]. In the case

when

[CK91]. In the case

when  is polynomial [BK78] or

algebraic [vdH02], then this complexity further reduces to

is polynomial [BK78] or

algebraic [vdH02], then this complexity further reduces to

. For some very special

series

. For some very special

series  , there even exist

, there even exist

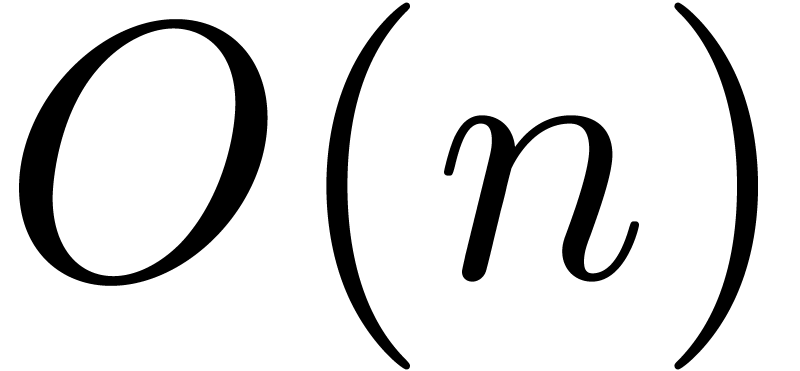

algorithms; see [BSS08] for an

overview. In positive characteristic

algorithms; see [BSS08] for an

overview. In positive characteristic  ,

right composition can also be performed in quasi-linear time

,

right composition can also be performed in quasi-linear time  [Ber98].

[Ber98].

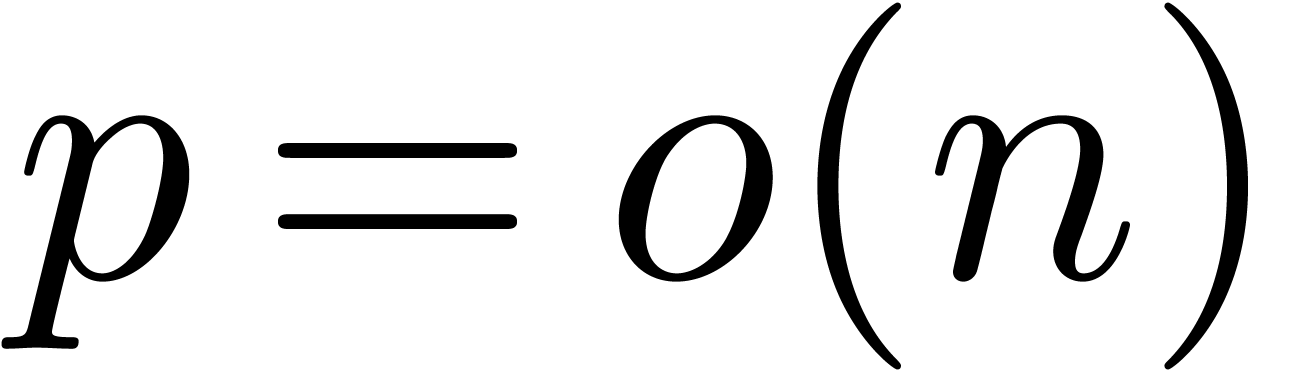

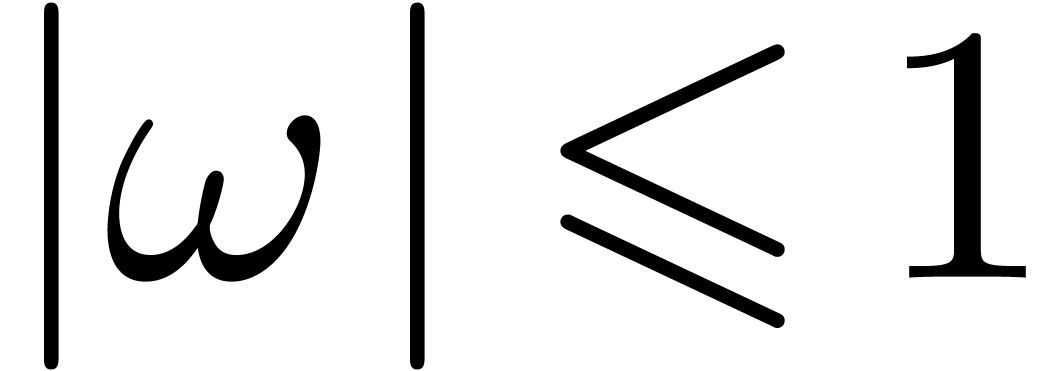

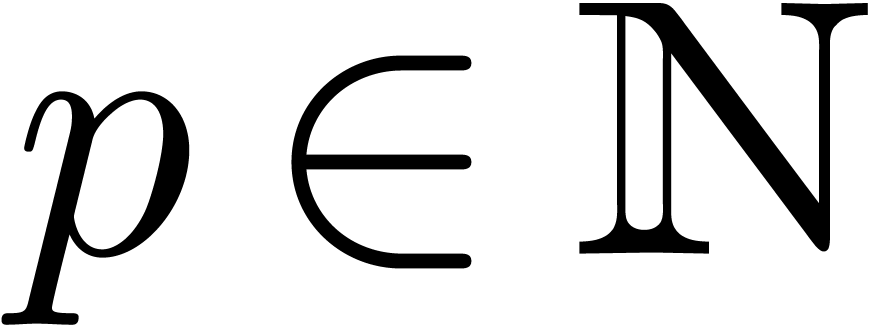

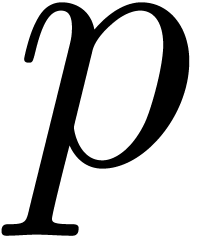

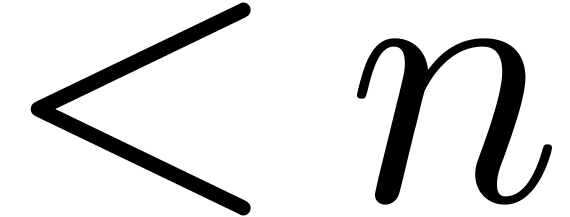

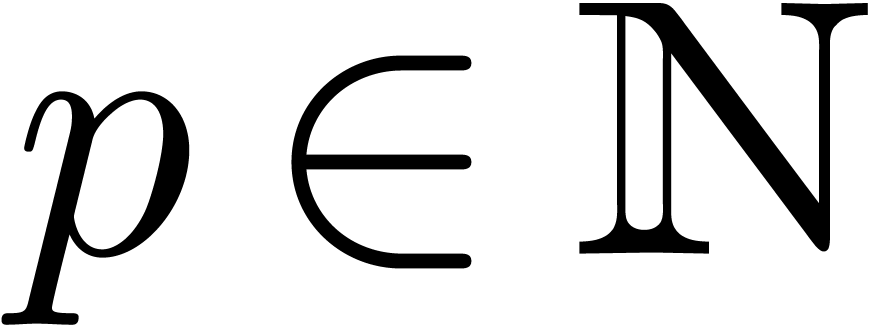

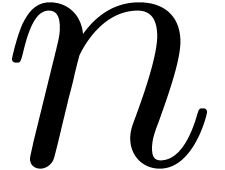

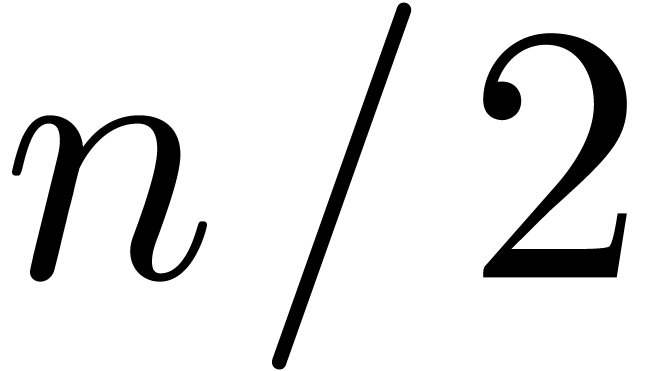

In this paper, we are interested in efficient algorithms when  is a ring of numbers, such as

is a ring of numbers, such as  ,

,  or a ring of floating

point numbers. In that case, we are interested in the bit complexity of

the composition, which means that we also have to take into account the

bit precision

or a ring of floating

point numbers. In that case, we are interested in the bit complexity of

the composition, which means that we also have to take into account the

bit precision  of the underlying integer

arithmetic. In particular, we will denote by

of the underlying integer

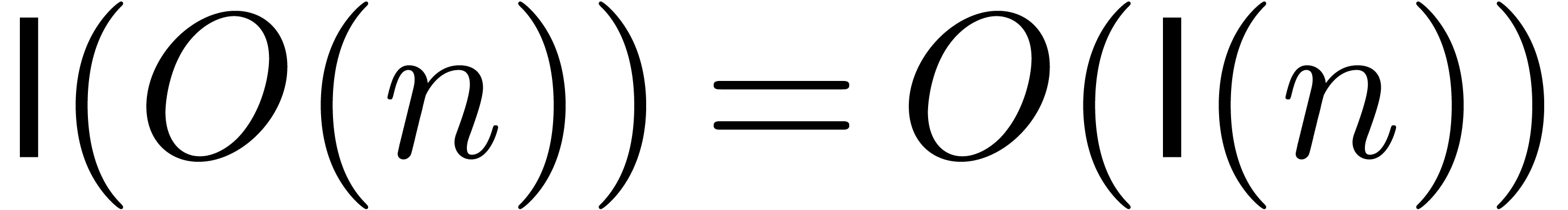

arithmetic. In particular, we will denote by  the

time needed for multiplying two

the

time needed for multiplying two  -bit

integers. We have

-bit

integers. We have  [SS71] and even

[SS71] and even

[Für07], where

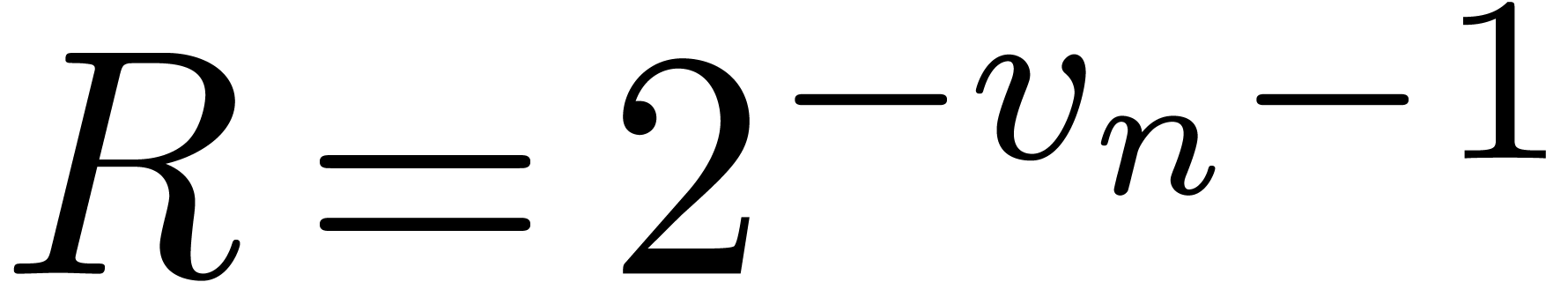

[Für07], where  satisfies

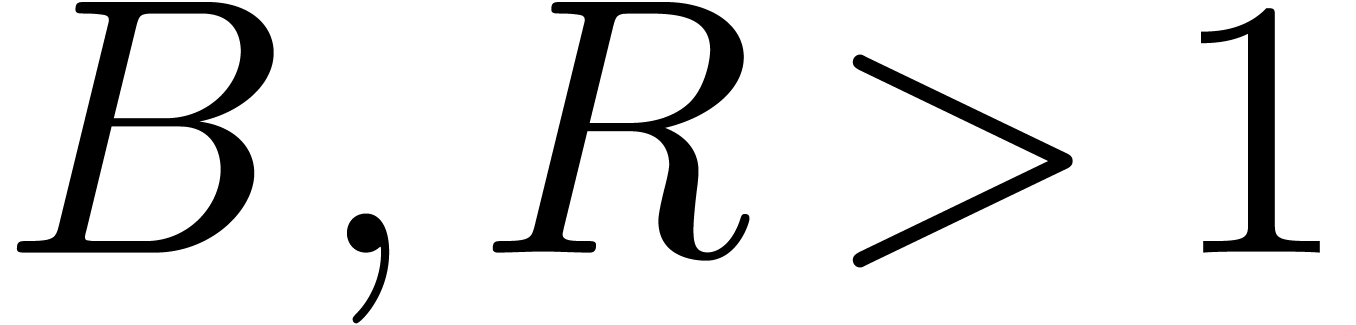

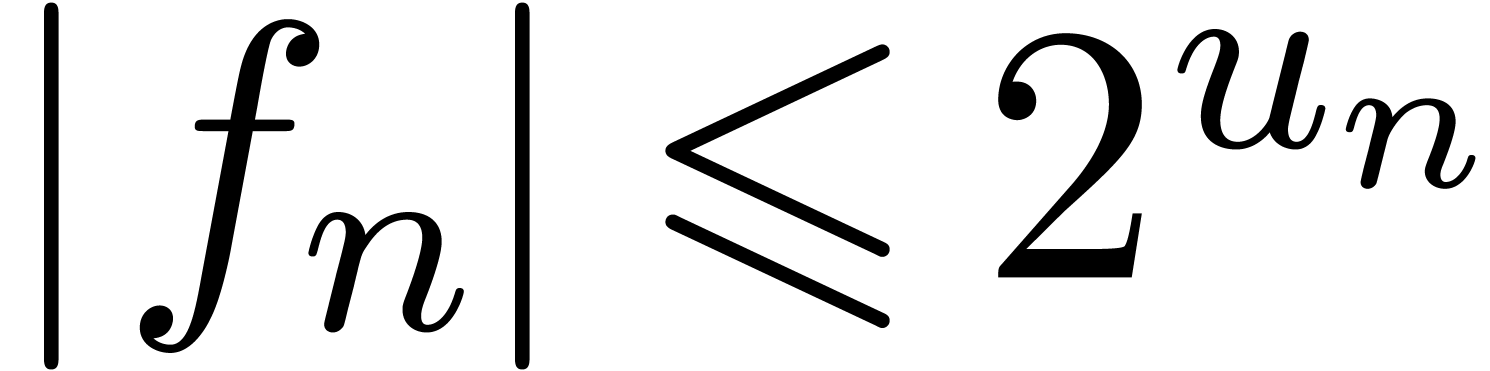

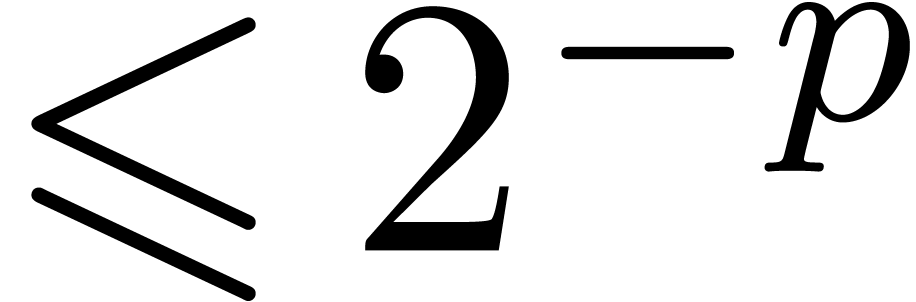

satisfies  . If

all coefficients

. If

all coefficients  ,

,  and

and  correspond to

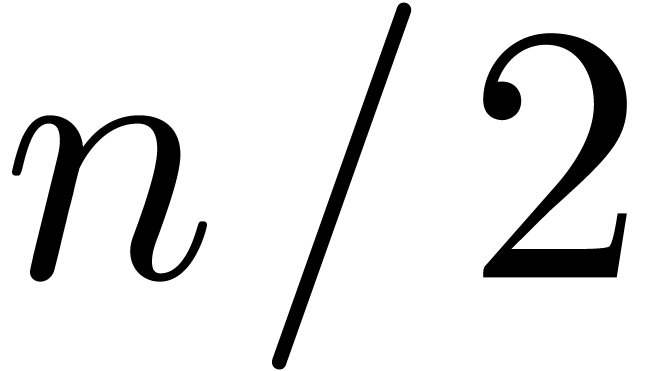

correspond to  -bit numbers, then we will search for a

composition algorithm which runs in quasi-linear time

-bit numbers, then we will search for a

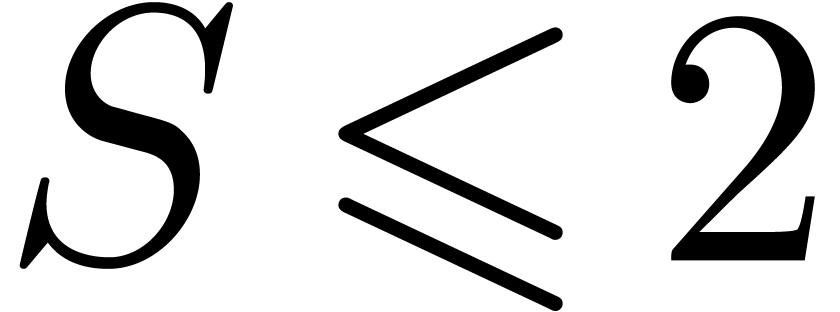

composition algorithm which runs in quasi-linear time  . Throughout the paper, we will assume that

. Throughout the paper, we will assume that

is increasing and

is increasing and  .

.

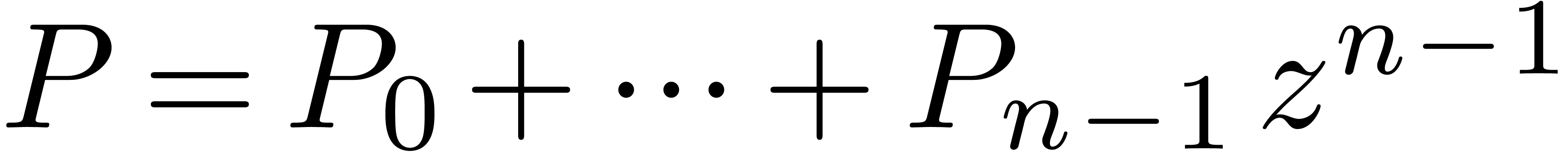

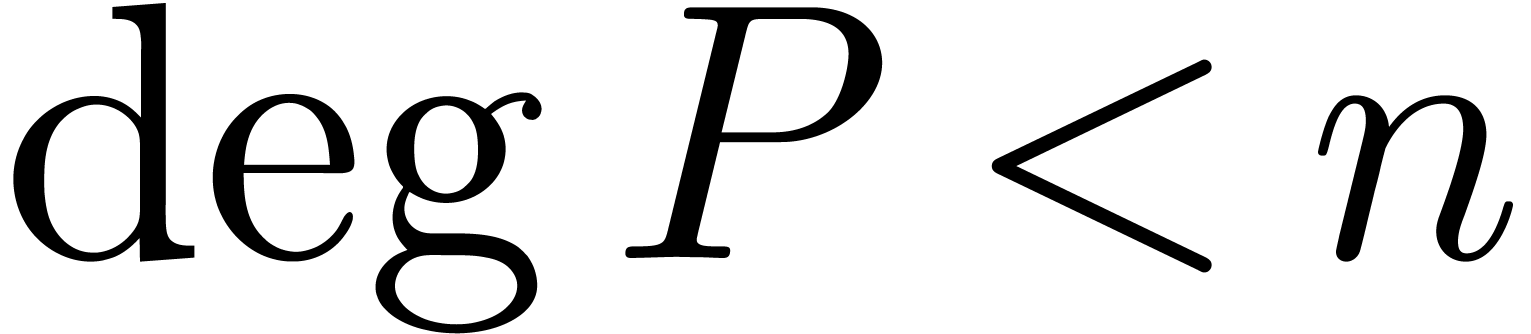

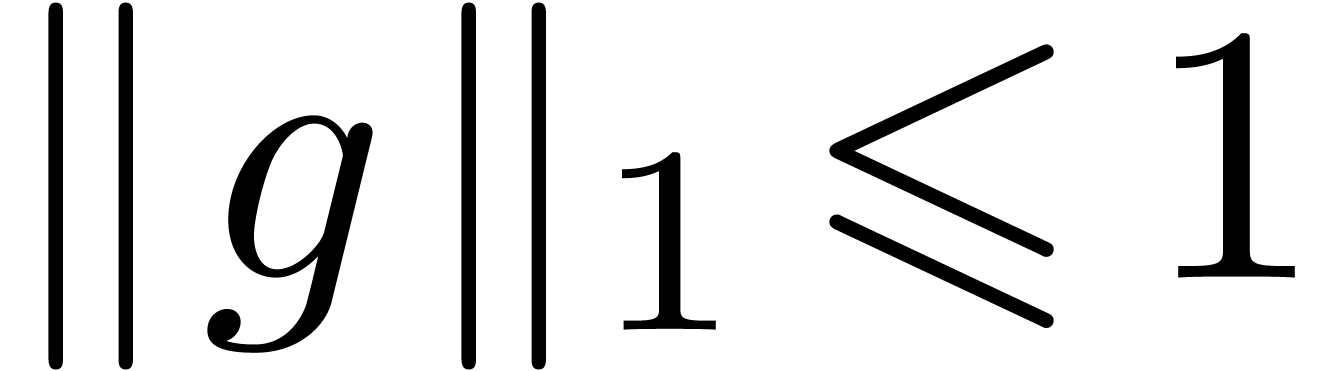

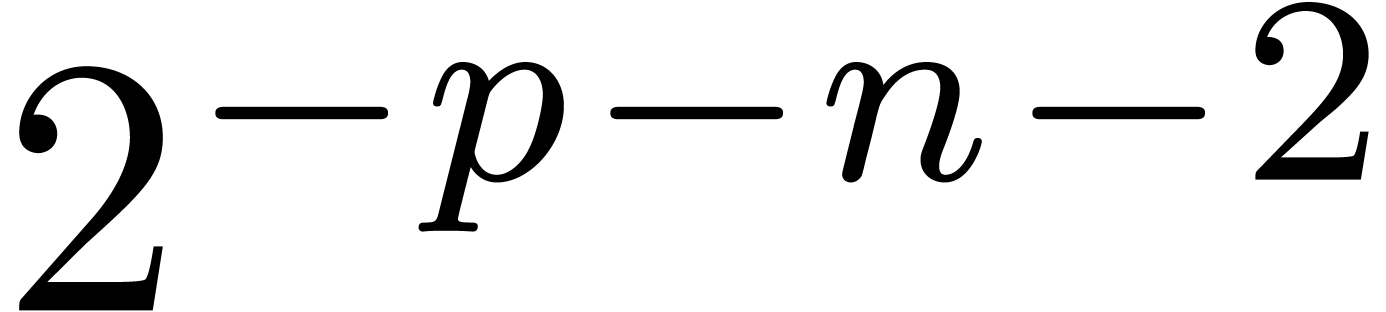

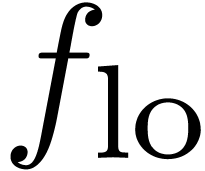

In section 2, we start by reviewing multiplication and

division of polynomials with numeric coefficients. Multiplication of two

polynomials of degrees  with

with  -bit coefficients can be done in time

-bit coefficients can be done in time  using Kronecker's substitution [Kro82].

Division essentially requires a higher complexity

using Kronecker's substitution [Kro82].

Division essentially requires a higher complexity  [Sch82], due to the fact that we may lose

[Sch82], due to the fact that we may lose  bits of precision when dividing by a polynomial of degree

bits of precision when dividing by a polynomial of degree  . Nevertheless, we will see that a best

possible complexity can be achieved in terms of the output precision.

. Nevertheless, we will see that a best

possible complexity can be achieved in terms of the output precision.

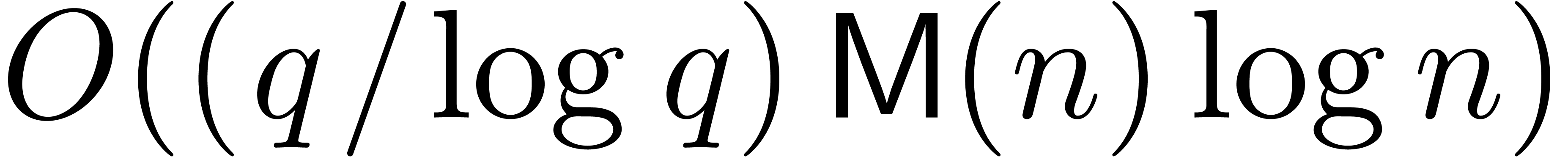

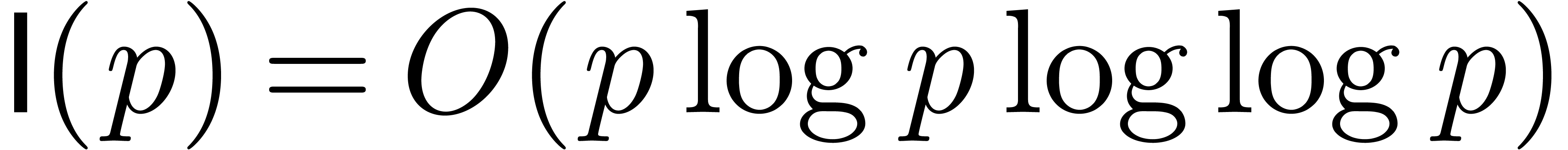

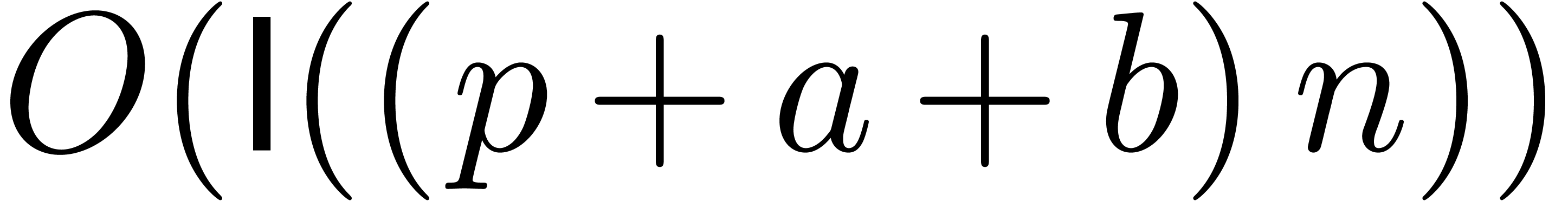

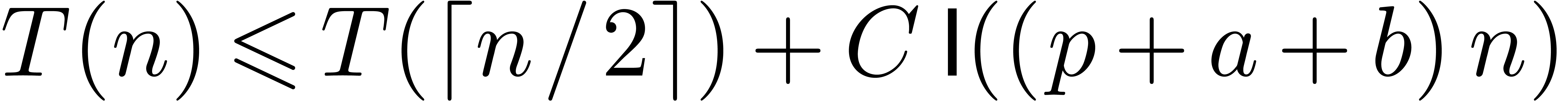

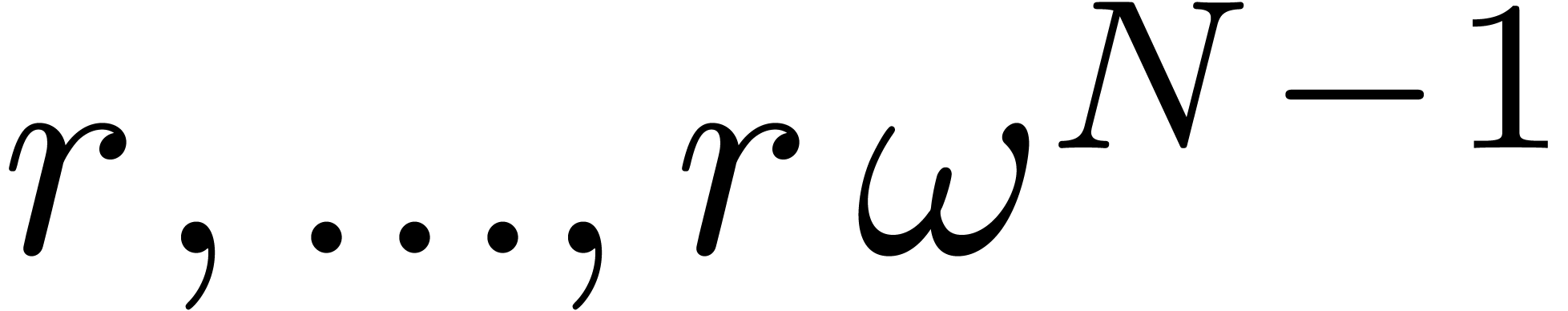

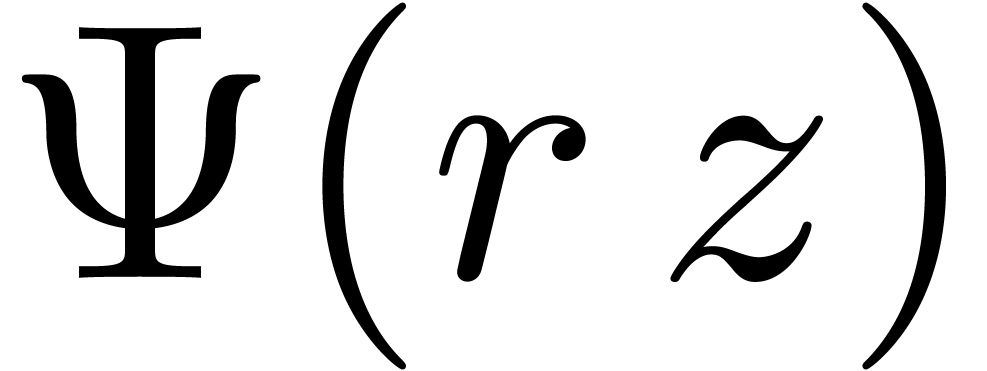

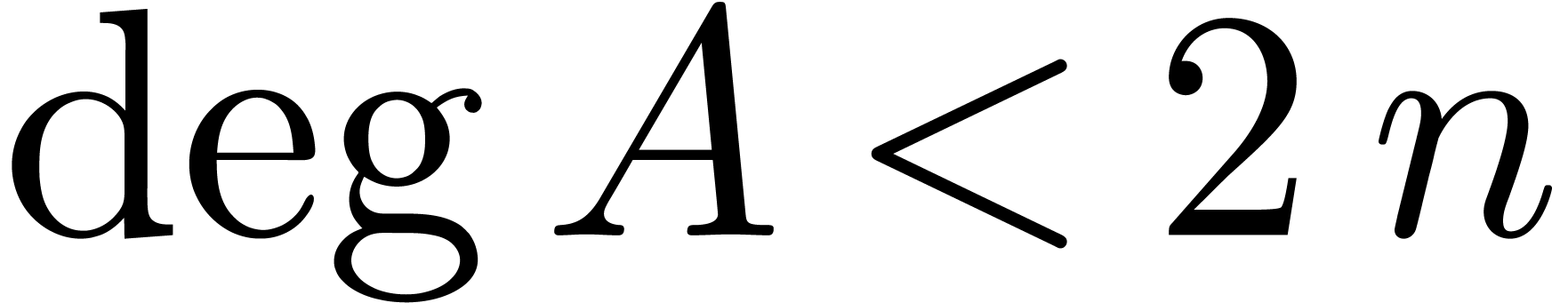

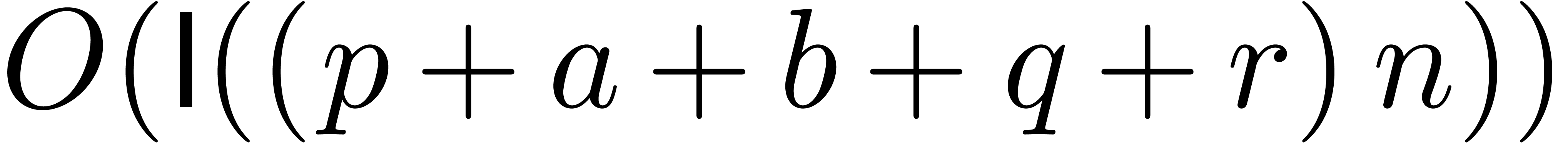

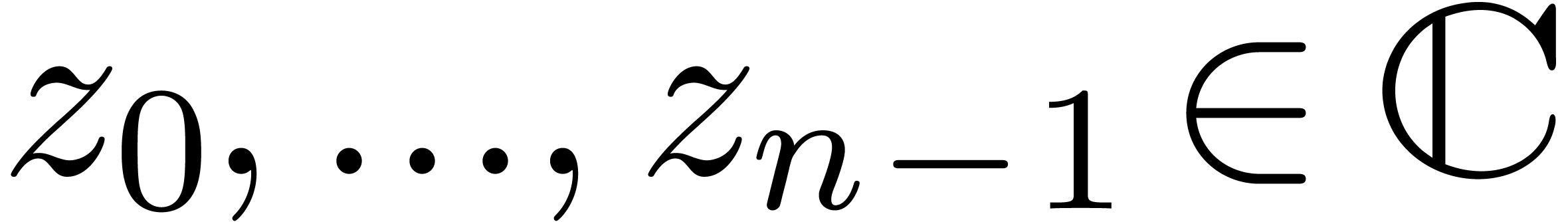

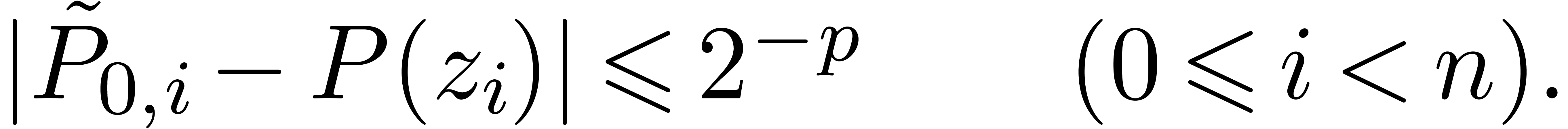

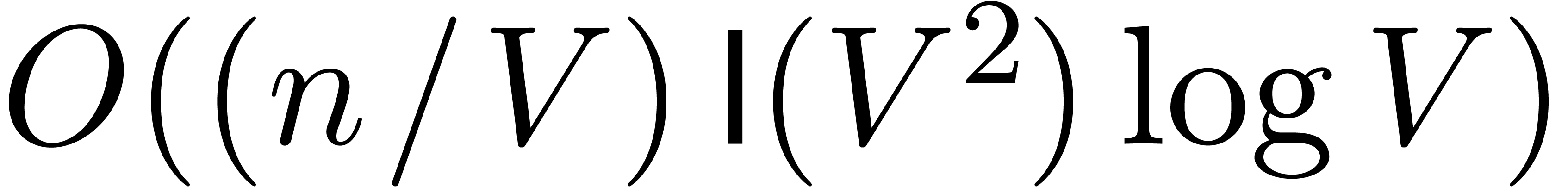

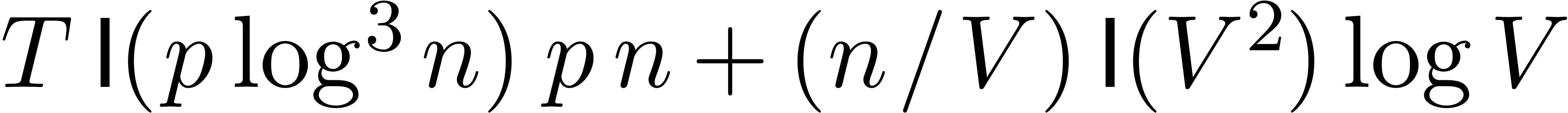

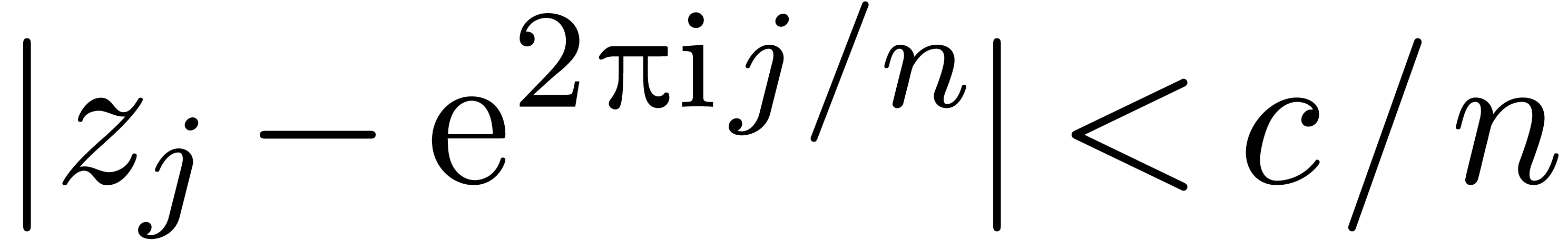

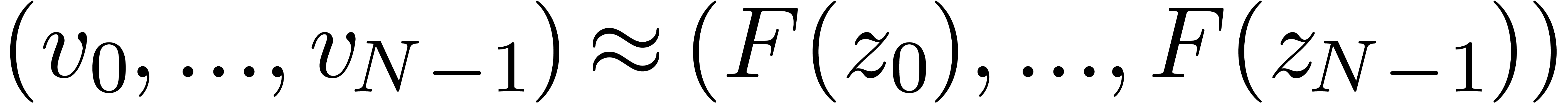

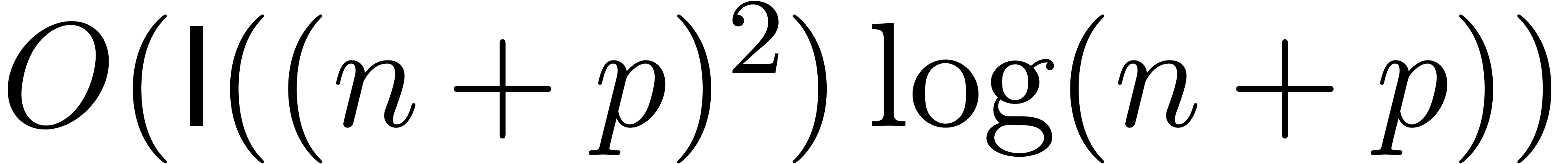

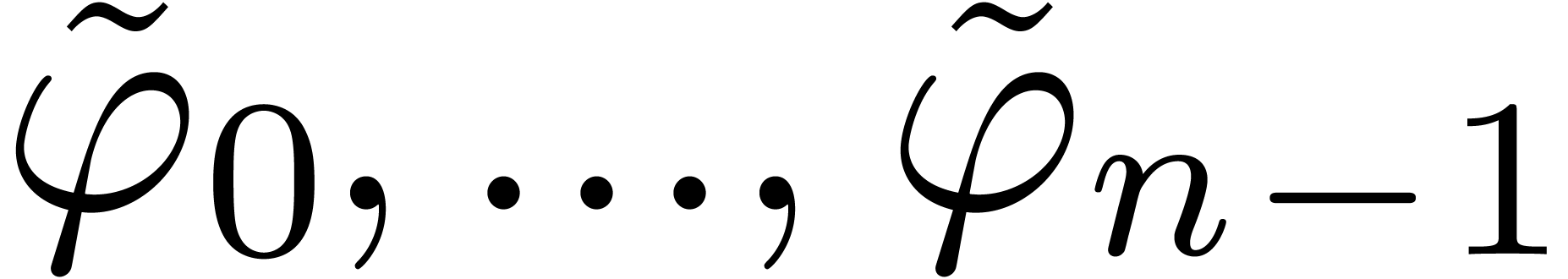

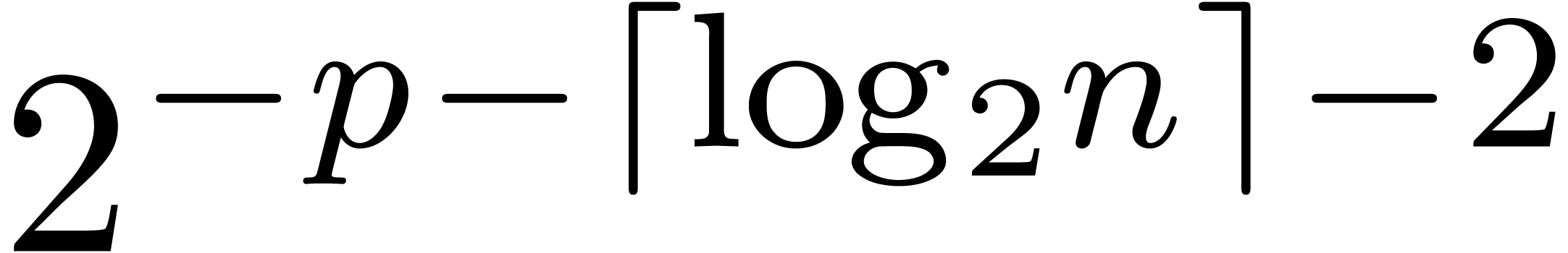

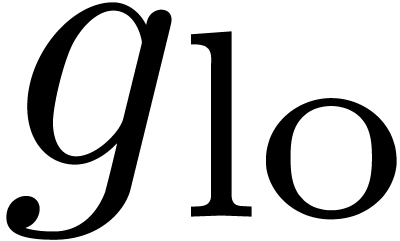

In section 3, we will study multi-point evaluation of a

polynomial  at

at  points

points

in the case of numeric coefficients. Adapting

the classical binary splitting algorithm [AHU74] of time

complexity

in the case of numeric coefficients. Adapting

the classical binary splitting algorithm [AHU74] of time

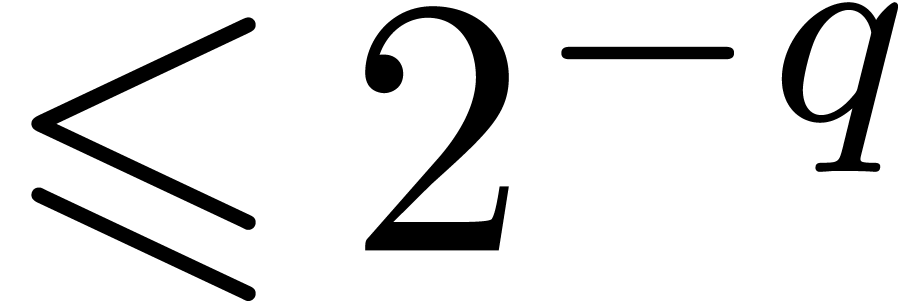

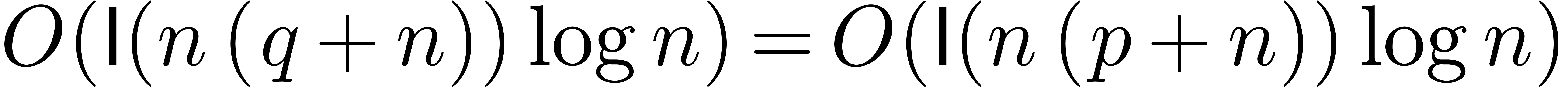

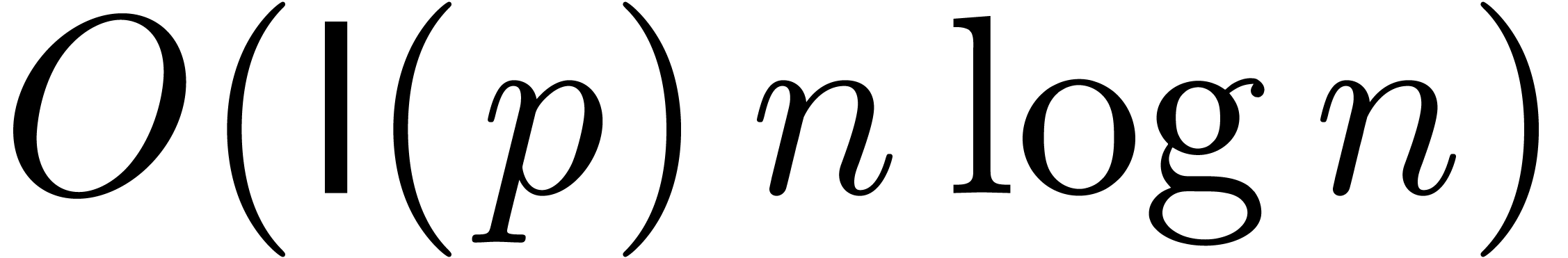

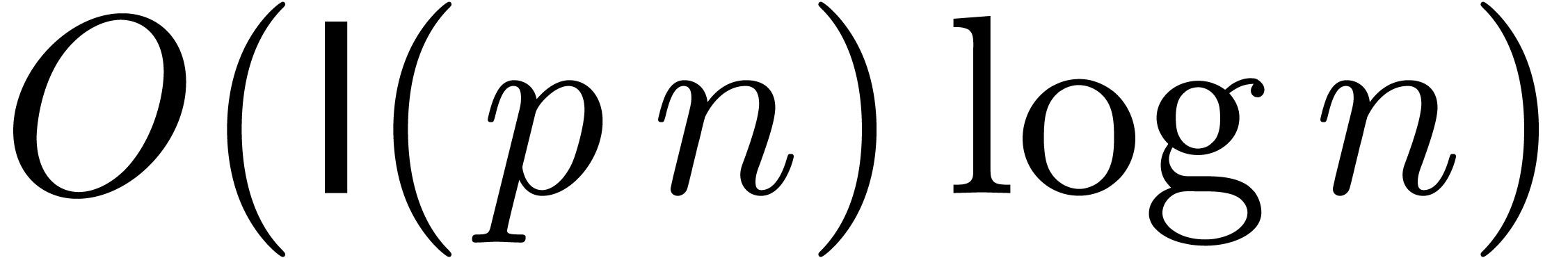

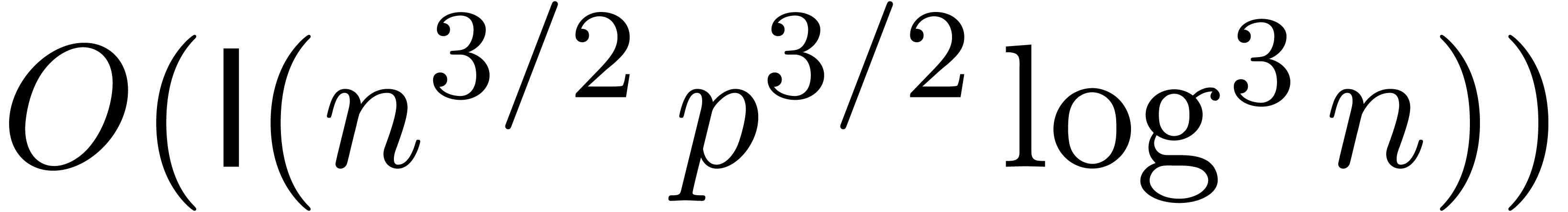

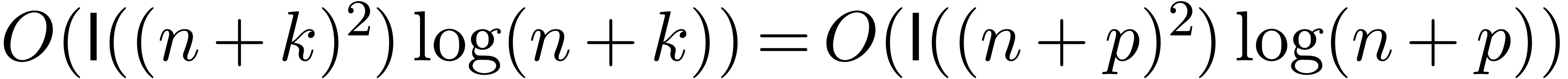

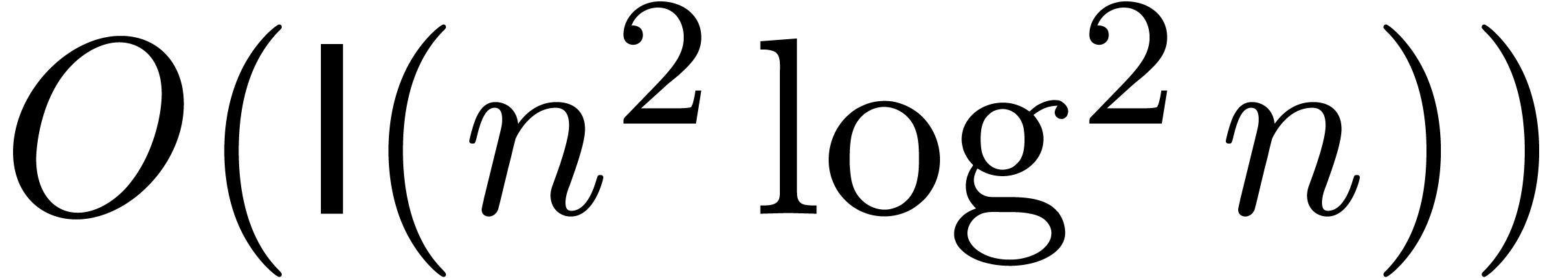

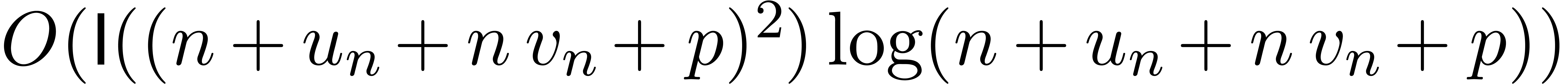

complexity  to the numeric context, we will prove

the complexity bound

to the numeric context, we will prove

the complexity bound  . In the

case when

. In the

case when  , this complexity

bound is again non-optimal in many cases. It would be nice if a bound of

the form

, this complexity

bound is again non-optimal in many cases. It would be nice if a bound of

the form  could be achieved and we will present

some ideas in this direction in section 3.2.

could be achieved and we will present

some ideas in this direction in section 3.2.

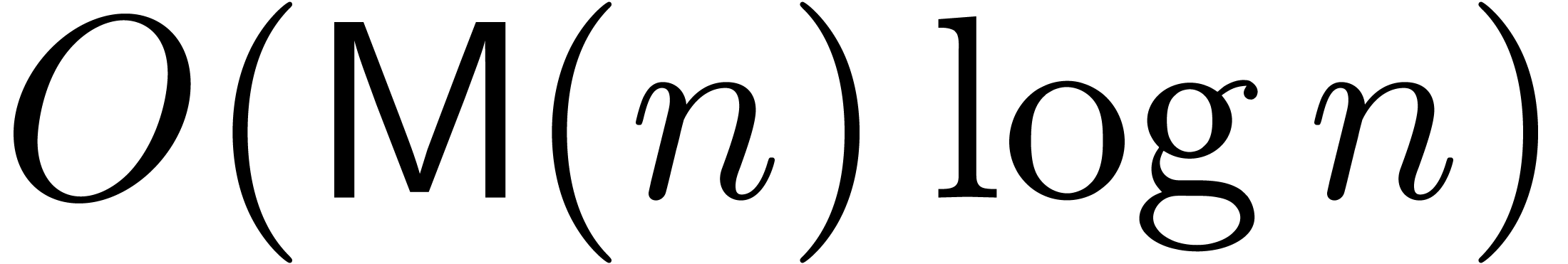

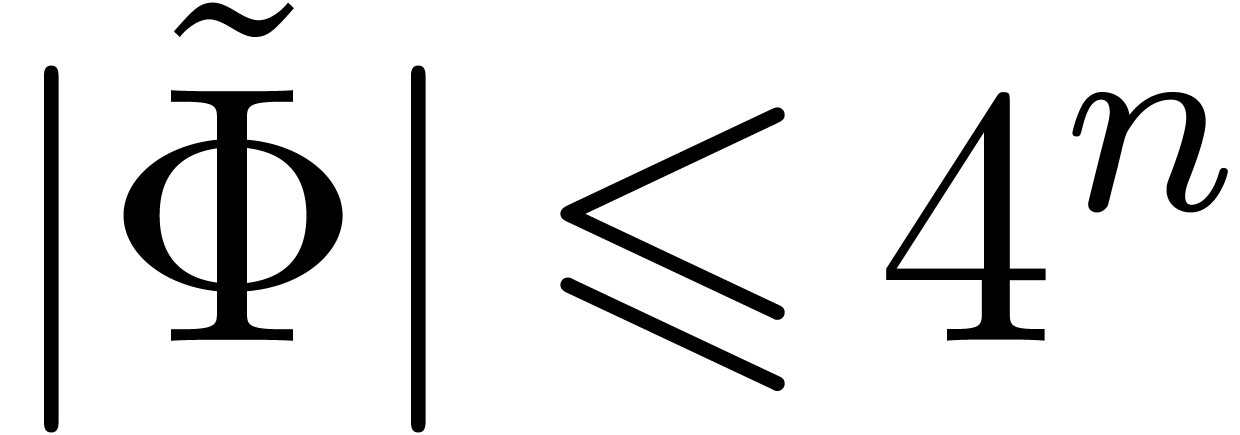

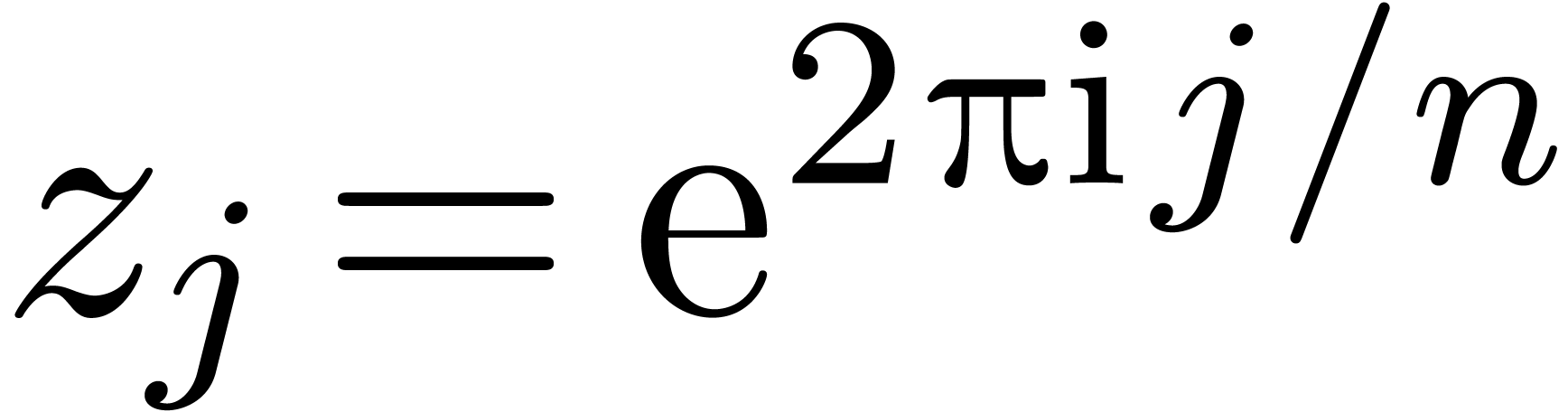

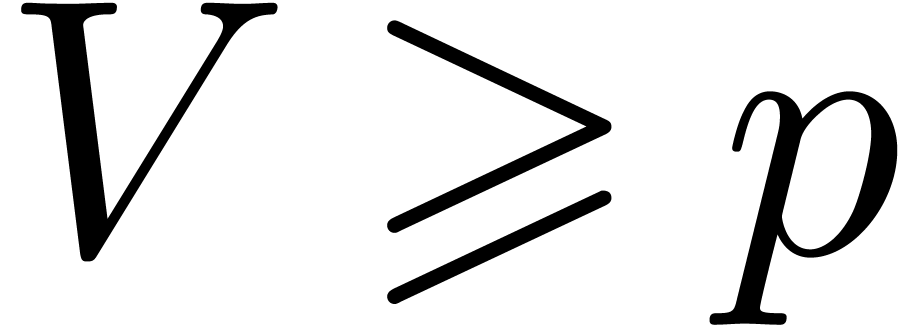

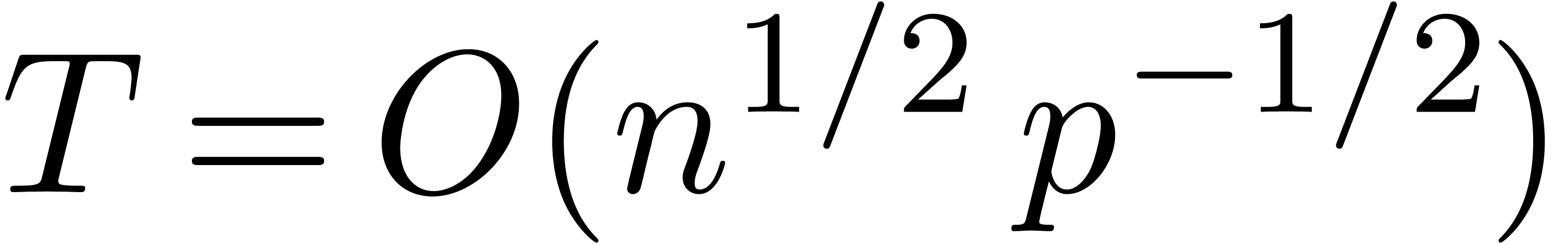

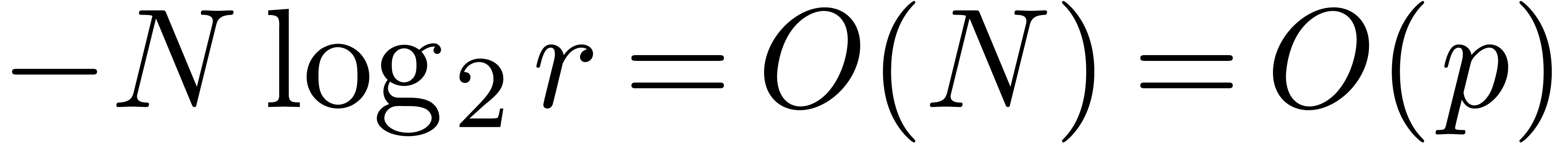

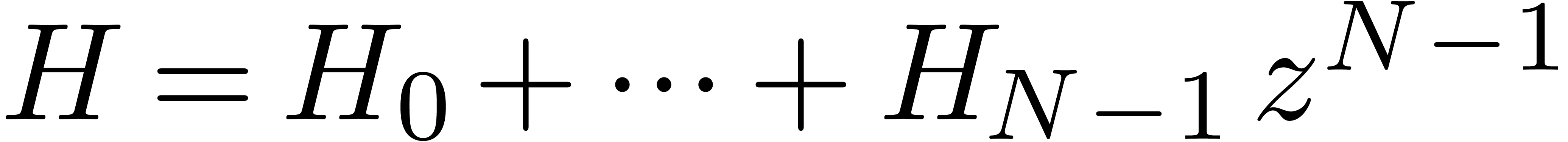

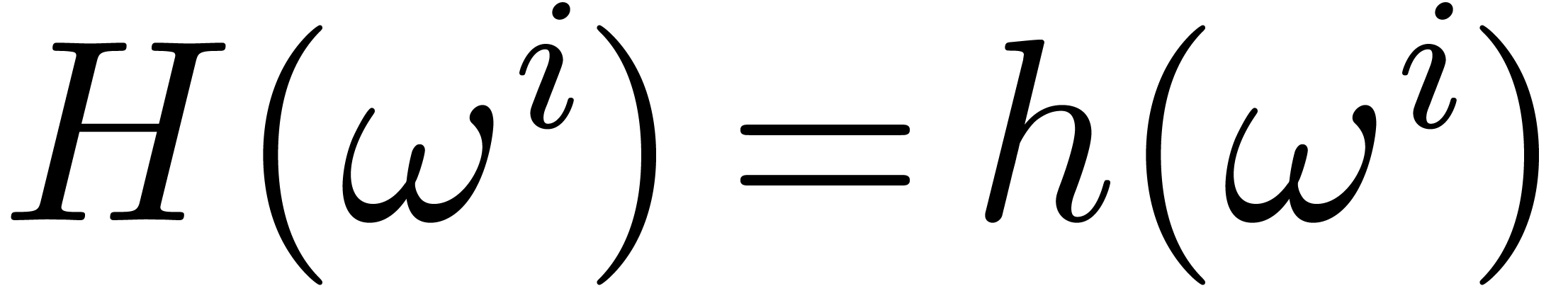

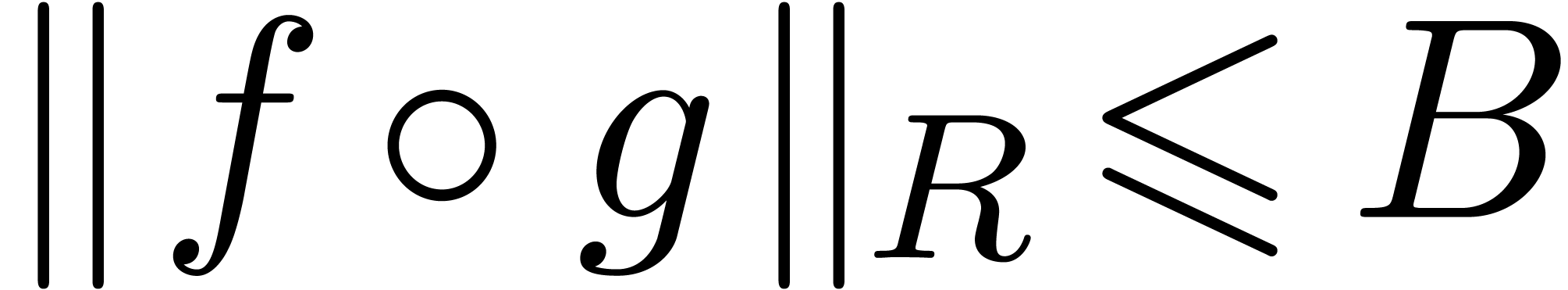

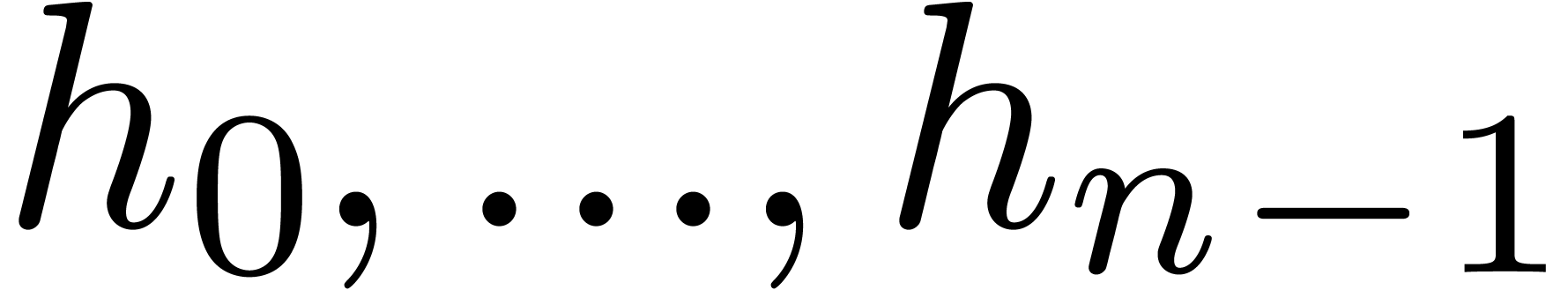

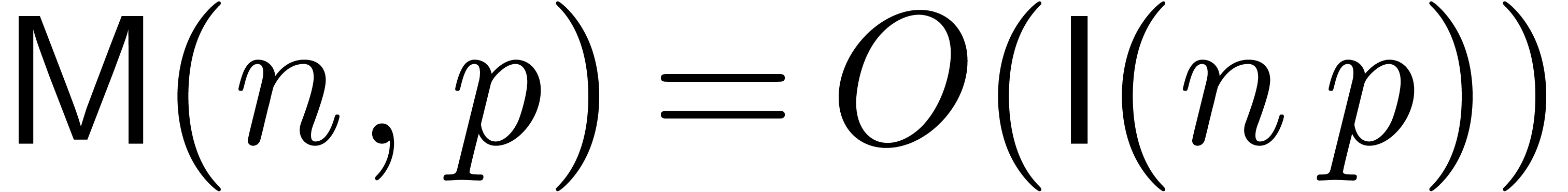

In section 4, we turn to the problem of numeric power

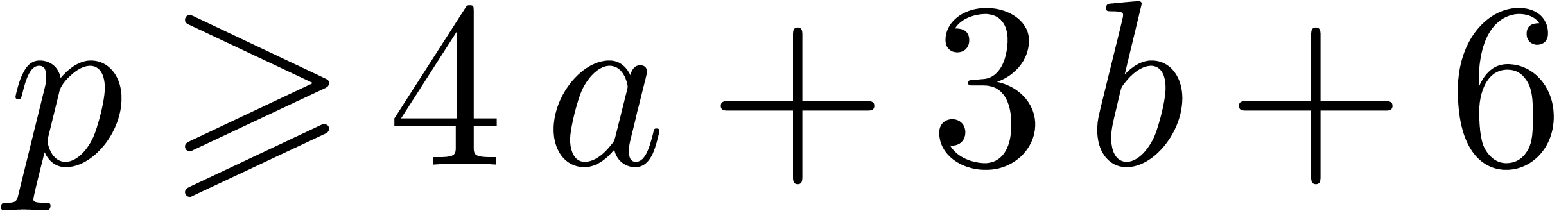

series composition. Under the assumptions  and

and

, we first show that the

computation of the first

, we first show that the

computation of the first  coefficients of a

convergent power series is essentially equivalent to its evaluation at

coefficients of a

convergent power series is essentially equivalent to its evaluation at

equally spaced points on a given circle (this

fact was already used in [Sch82], although not stated as

explicitly). The composition problem can therefore be reduced to one

fast Fourier transform, one multi-point evaluation and one inverse

Fourier transform, leading to a complexity

equally spaced points on a given circle (this

fact was already used in [Sch82], although not stated as

explicitly). The composition problem can therefore be reduced to one

fast Fourier transform, one multi-point evaluation and one inverse

Fourier transform, leading to a complexity  .

We first prove this result under certain normalization conditions for

floating point coefficients. We next extend the result to different

types of numeric coefficients (including integers and rationals) and

also consider non-convergent series. The good complexity of these

algorithms should not come as a full surprise: under the analogy

numbers

.

We first prove this result under certain normalization conditions for

floating point coefficients. We next extend the result to different

types of numeric coefficients (including integers and rationals) and

also consider non-convergent series. The good complexity of these

algorithms should not come as a full surprise: under the analogy

numbers series, it was already

known [BK77] how to compose multivariate power

series fast.

series, it was already

known [BK77] how to compose multivariate power

series fast.

In the last section, we conclude by giving relaxed versions [vdH02] of our composition algorithm. This allows for the resolution of functional equations for numeric power series, involving composition. Unfortunately, we did not yet achieve a quasi-linear bound, even though some progress has been made on the exponent. The special case of power series reversion may be reduced more directly to composition, using Newton's method [BK75].

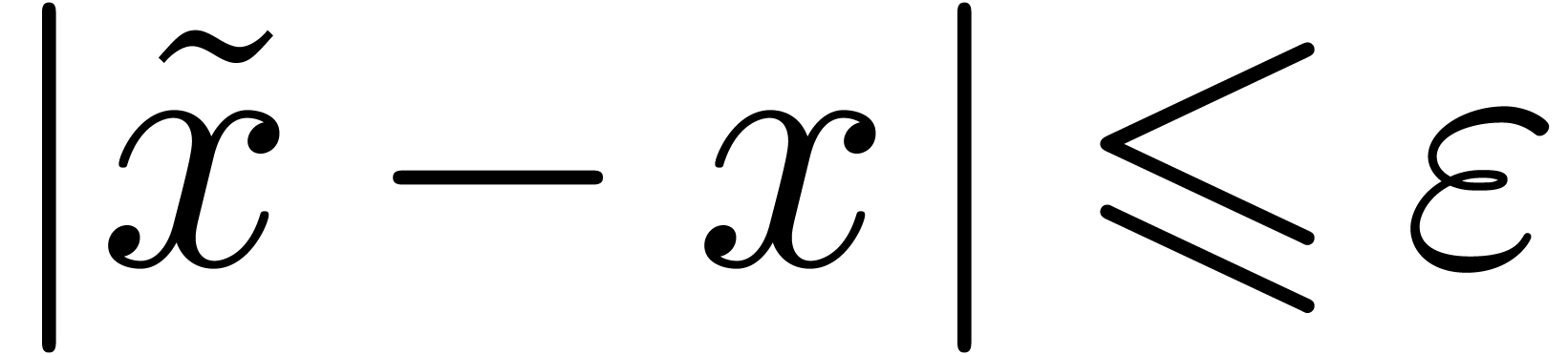

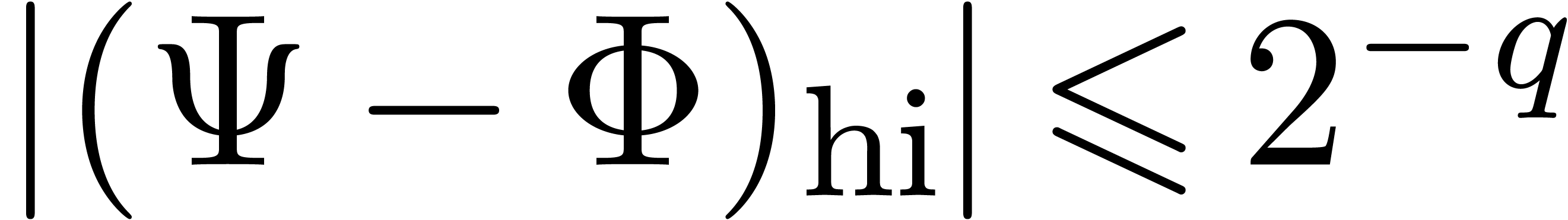

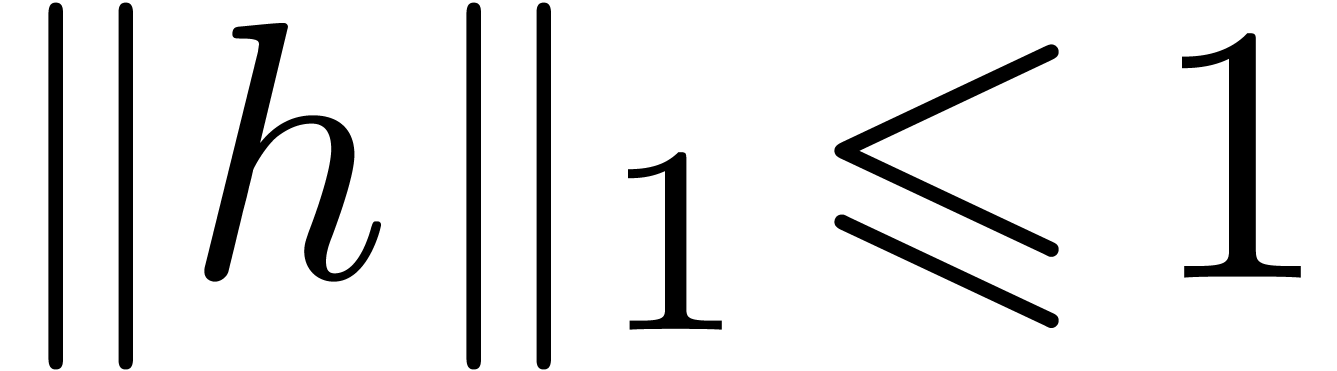

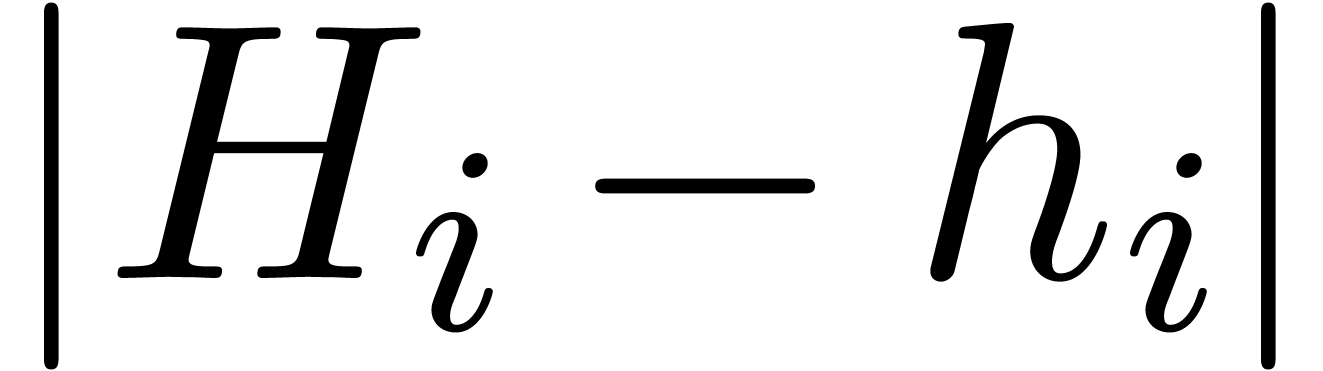

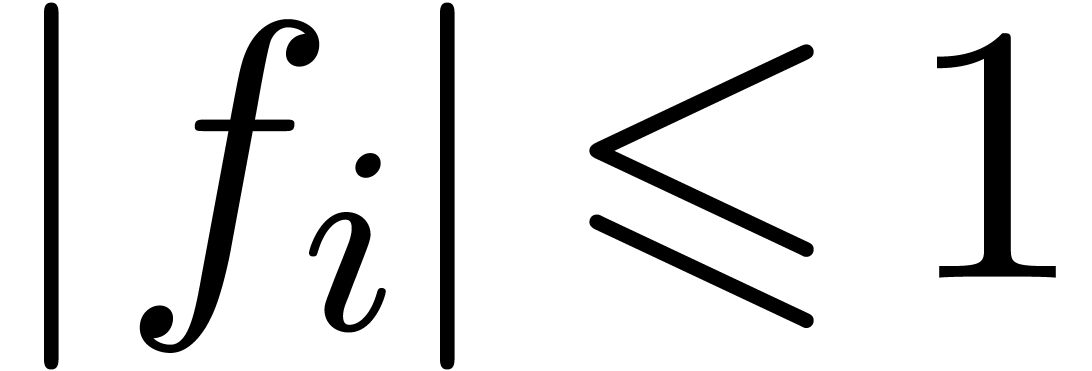

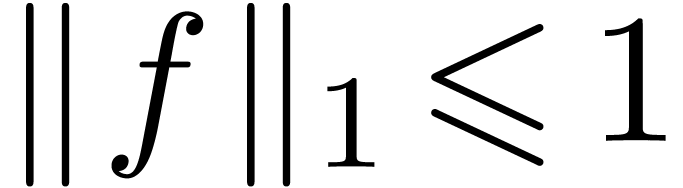

Let  be a normed vector space. Given

be a normed vector space. Given  and

and  , we say

that

, we say

that  is an

is an  -approximation

of

-approximation

of  if

if  .

We will also say that

.

We will also say that  is an approximation of

is an approximation of

with absolute error

with absolute error  or an absolute precision of

or an absolute precision of  bits. For

polynomials

bits. For

polynomials  , we will use the

norm

, we will use the

norm  , and notice that

, and notice that  . For vectors

. For vectors  , we will use the norm

, we will use the norm  .

.

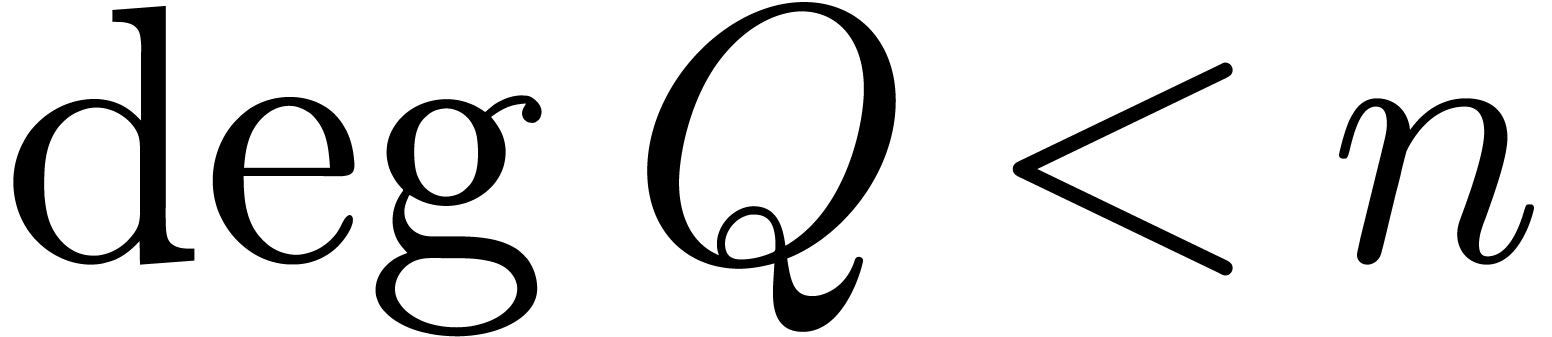

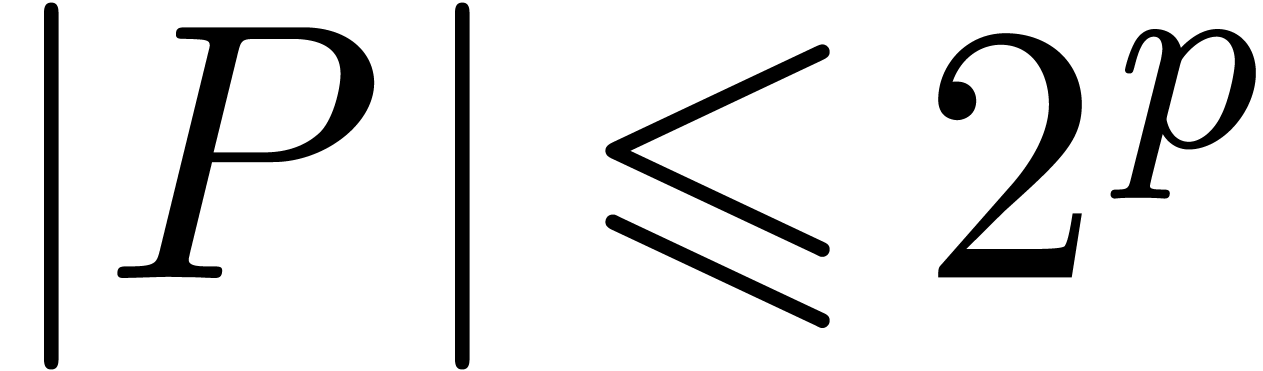

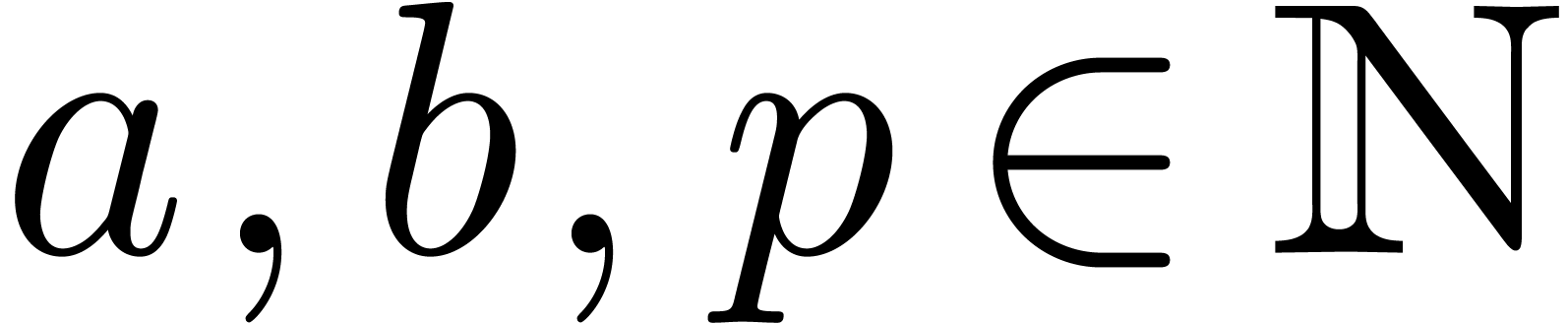

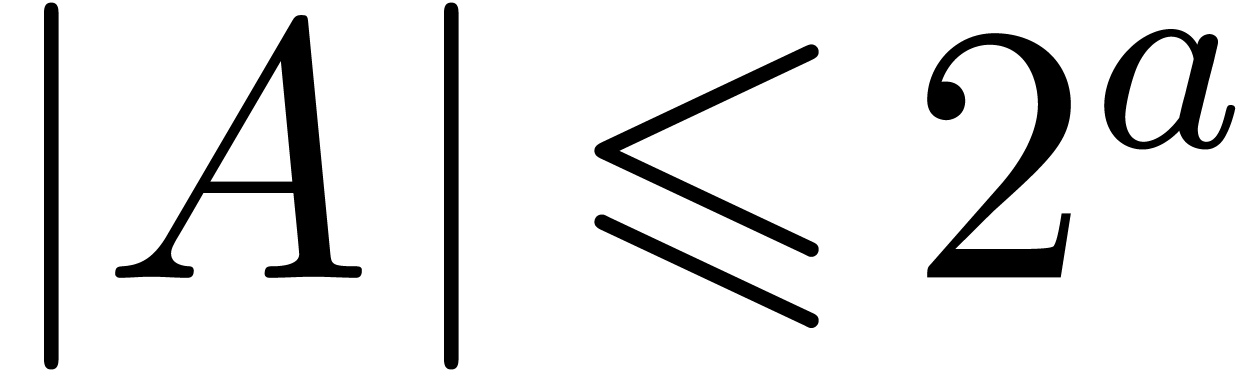

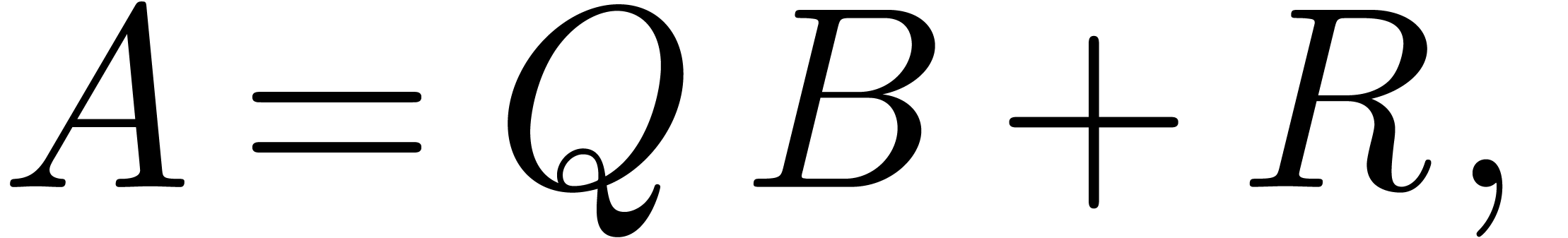

Given two polynomials  with

with  ,

,  ,

,

and

and  ,

take

,

take  . Then the product

. Then the product  can be read off from the integer product

can be read off from the integer product  , since the coefficients of the result all fit

into

, since the coefficients of the result all fit

into  bits. This method is called Kronecker

multiplication [Kro82] and its cost is bounded by

bits. This method is called Kronecker

multiplication [Kro82] and its cost is bounded by  . Clearly, the method generalizes

to the case when

. Clearly, the method generalizes

to the case when  or

or  . A direct consequence for the computation with

floating point polynomials is the following:

. A direct consequence for the computation with

floating point polynomials is the following:

be two polynomials with

be two polynomials with  . Given

. Given  with

with  and

and  , we may

compute a

, we may

compute a  -approximation of

-approximation of

in time

in time  .

.

Proof. Let  and consider

polynomials

and consider

polynomials  with

with

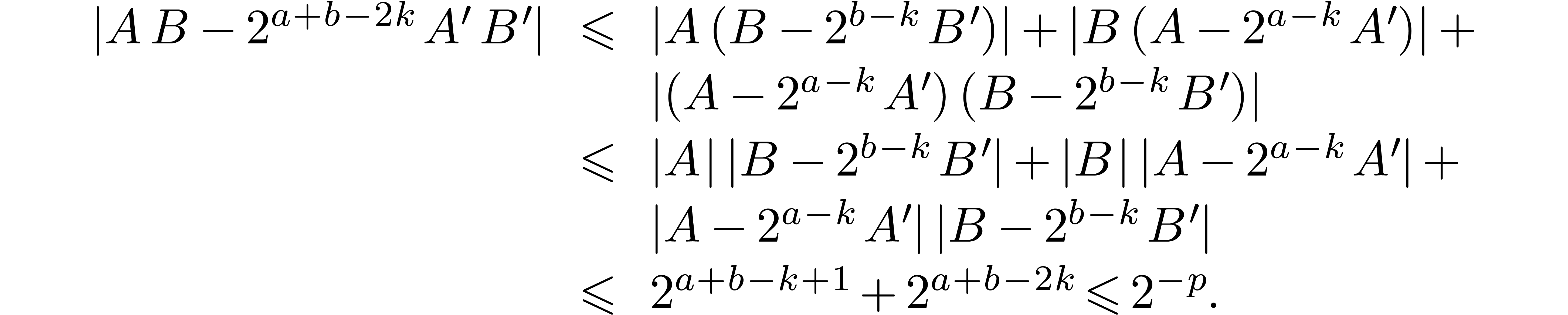

By assumption, the bit-sizes of the coefficients of  and

and  are bounded by

are bounded by  .

Therefore, we may compute the exact product

.

Therefore, we may compute the exact product  in

time

in

time  , using Kronecker

multiplication. We have

, using Kronecker

multiplication. We have

This proves that  is a

is a  -approximation of

-approximation of  .

One may optionally truncate the mantissas of the coefficients of

.

One may optionally truncate the mantissas of the coefficients of  so as to fit into

so as to fit into  bits.

bits.

Remark

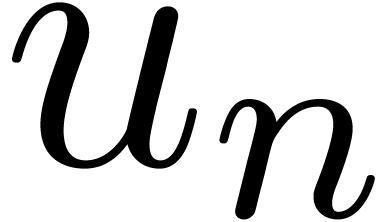

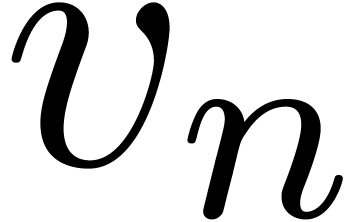

be such that

be such that  for all

for all

and

and

Let  and

and  .

Let

.

Let  be such that

be such that  and

and

. Given

. Given  , we may compute a

, we may compute a  -approximation of

-approximation of  in time

in time

.

.

Proof. Assume that we are given an approximation

of

of  .

Then we may compute a better approximation using the classical Newton

iteration

.

Then we may compute a better approximation using the classical Newton

iteration

|

(1) |

If  is “small”, then

is “small”, then

|

(2) |

is about twice as “small”. We will apply the Newton

iteration for a polynomial  whose first

whose first  coefficients are good approximations of

coefficients are good approximations of  and the remaining coefficients less good approximations.

and the remaining coefficients less good approximations.

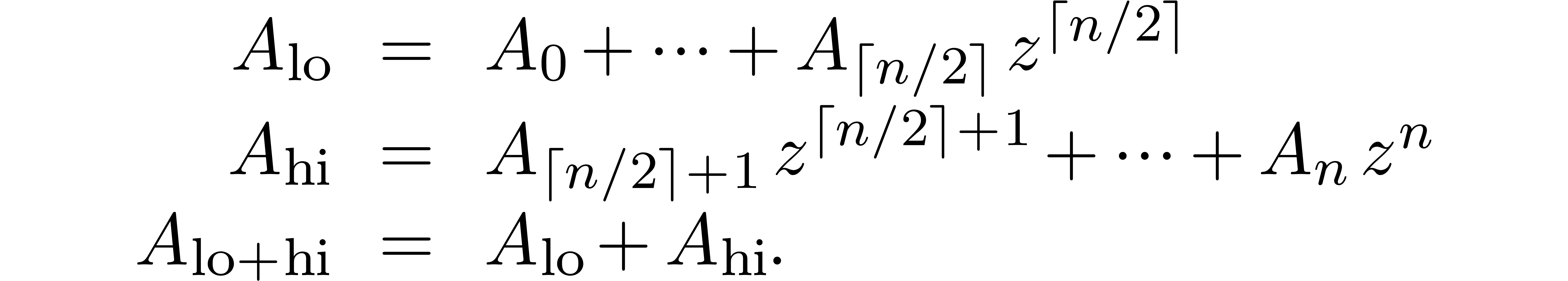

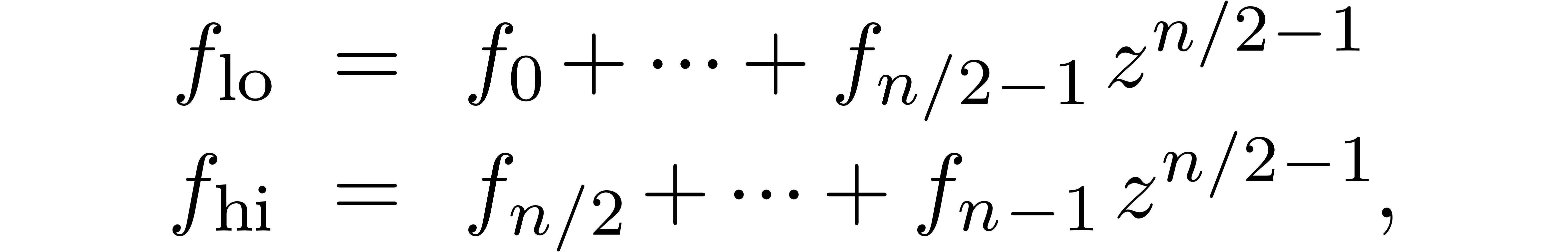

Given a polynomial  , we write

, we write

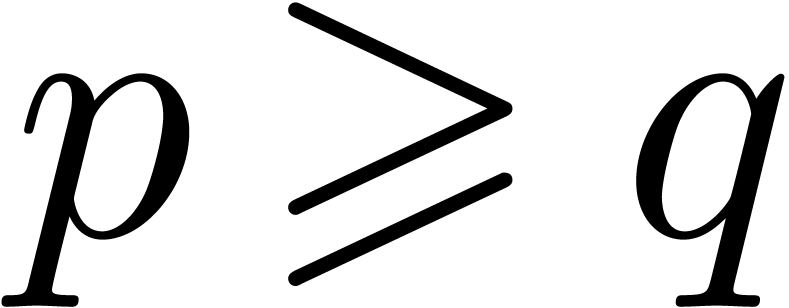

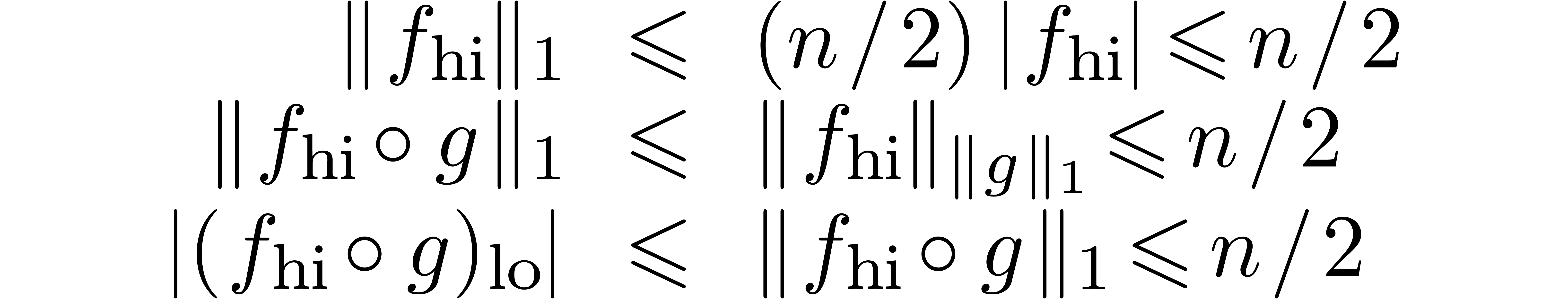

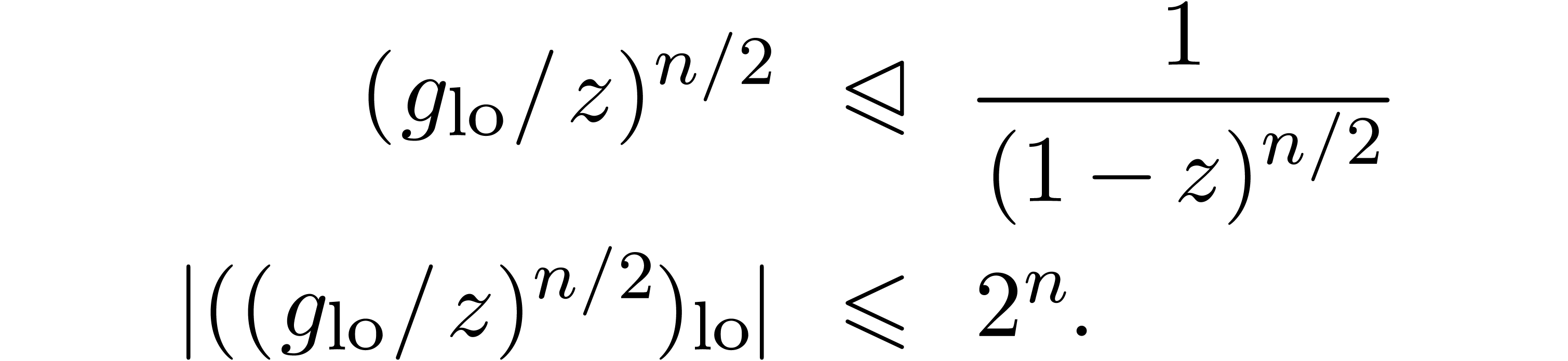

Assume that  and

and  ,

with

,

with  . Setting

. Setting  and

and  , we have

, we have

The relation (2) yields

whence

When starting with  , we may

take

, we may

take  . If

. If  is sufficiently large, then one Newton iteration yields

is sufficiently large, then one Newton iteration yields  . Applying the Newton iteration once more for

. Applying the Newton iteration once more for

, we obtain

, we obtain  . In view of lemma 1 and the

assumption

. In view of lemma 1 and the

assumption  , the cost of two

such Newton iterations is bounded by

, the cost of two

such Newton iterations is bounded by  for a

suitable constant

for a

suitable constant  .

.

We are now in a position to prove the lemma. Since an increase of  by

by  leaves the desired

complexity bound unaltered, we may assume without loss of generality

that

leaves the desired

complexity bound unaltered, we may assume without loss of generality

that  . Then the cost

. Then the cost  of the inversion at order

of the inversion at order  satisfies

satisfies  . We conclude that

. We conclude that

.

.

Remark  is given, then a constant

is given, then a constant  for

the bound

for

the bound  is not known a priori. Assume

that

is not known a priori. Assume

that  and write

and write  .

Then

.

Then  and

and

Assuming  , it follows that

, it follows that

We may thus take  . Inversely,

we have

. Inversely,

we have

In other words, our choice of  is at most a

factor two worse than the optimal value.

is at most a

factor two worse than the optimal value.

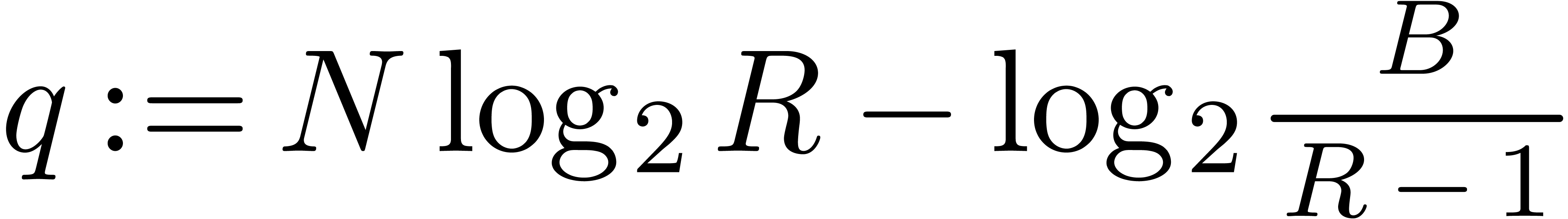

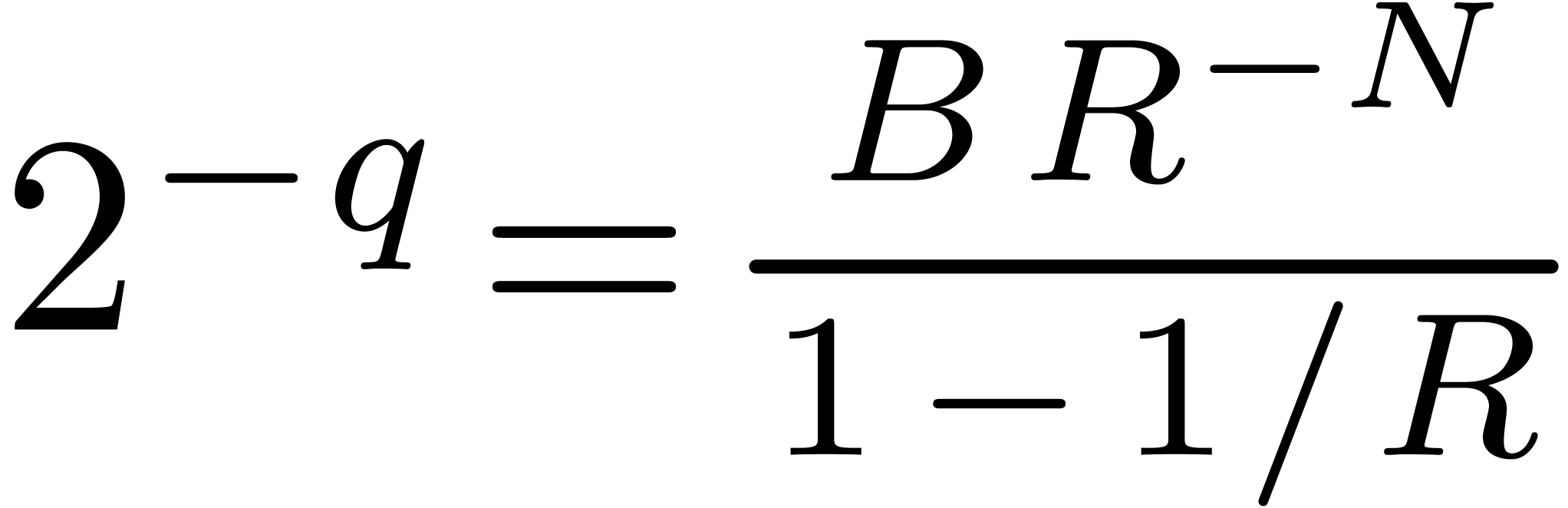

Remark  is a variant of the method described in [Sch82,

Section 4]:

is a variant of the method described in [Sch82,

Section 4]:

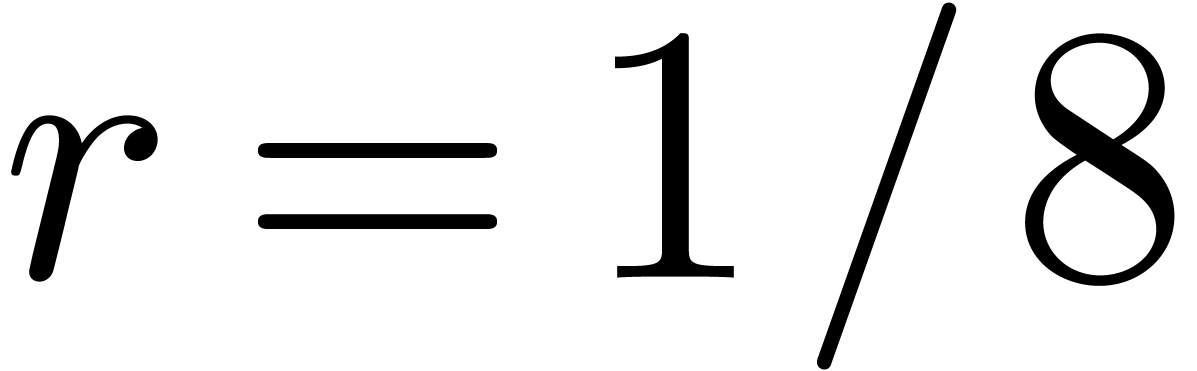

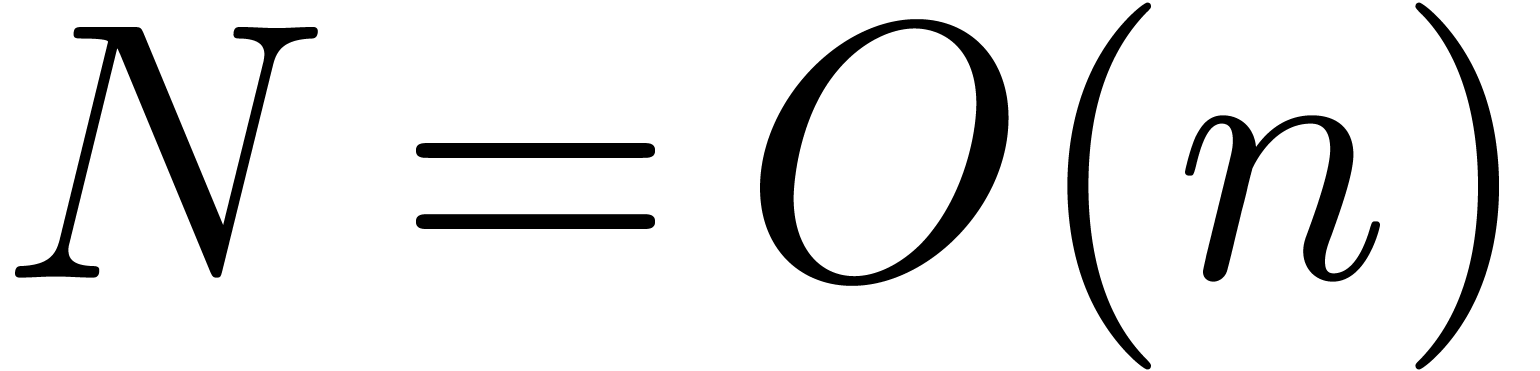

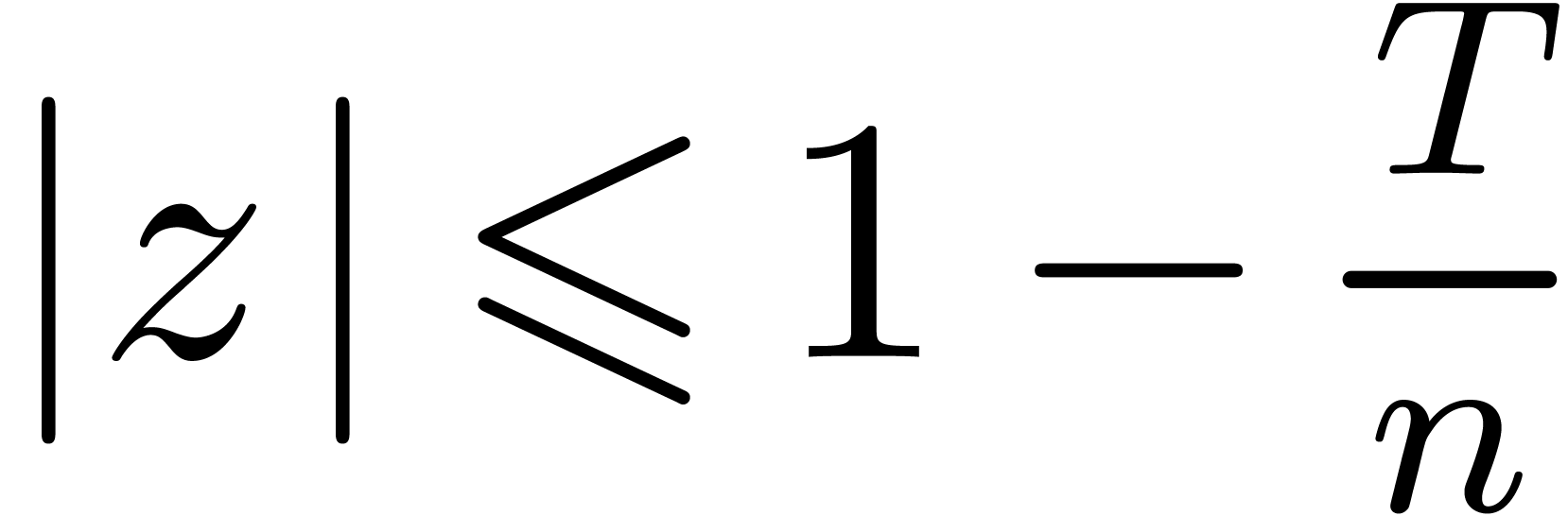

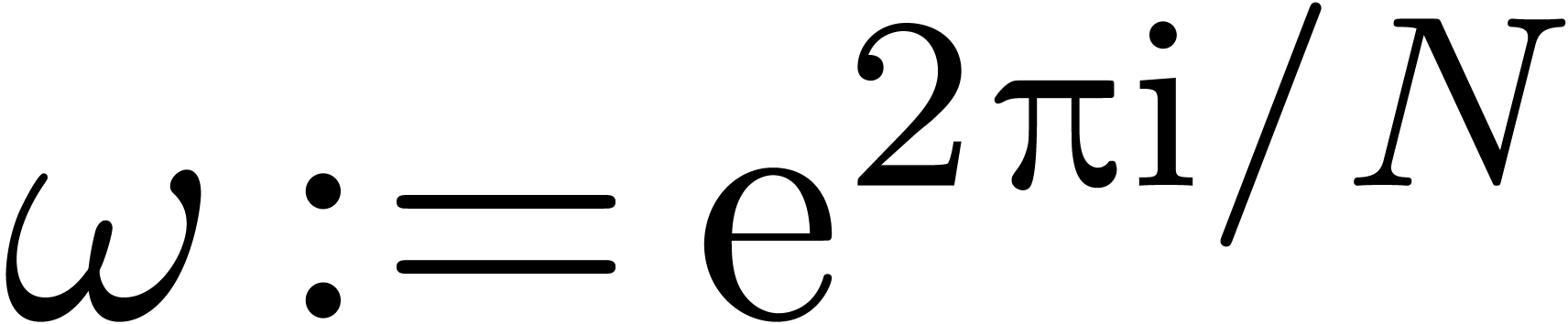

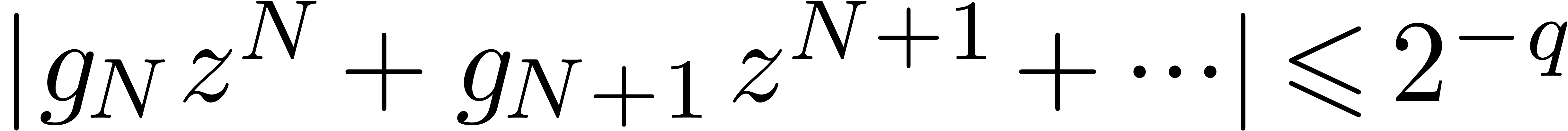

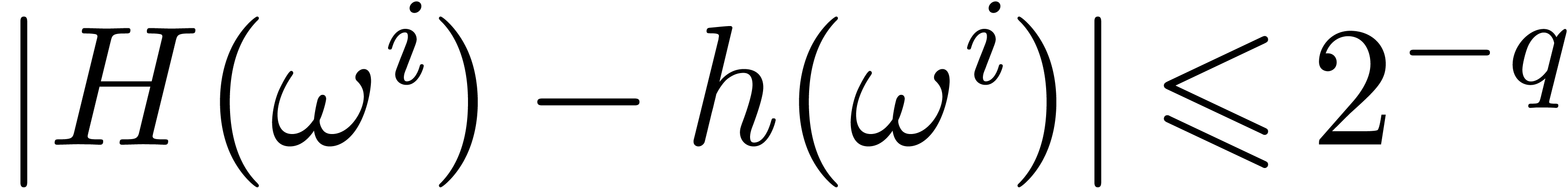

Choose  sufficiently small and

sufficiently small and  sufficiently large, such that

sufficiently large, such that

|

(3) |

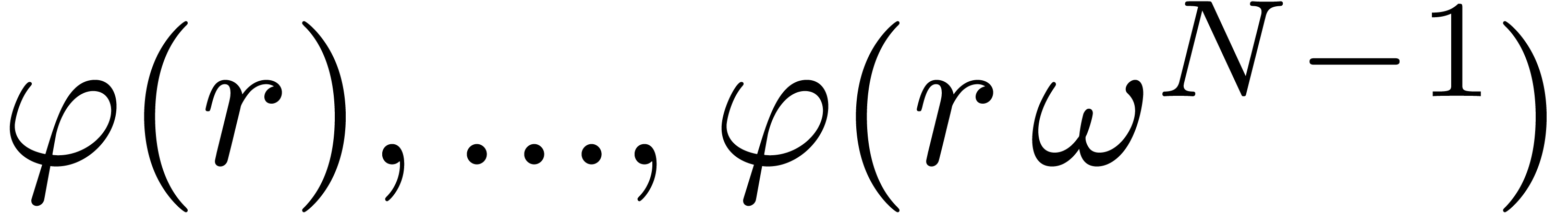

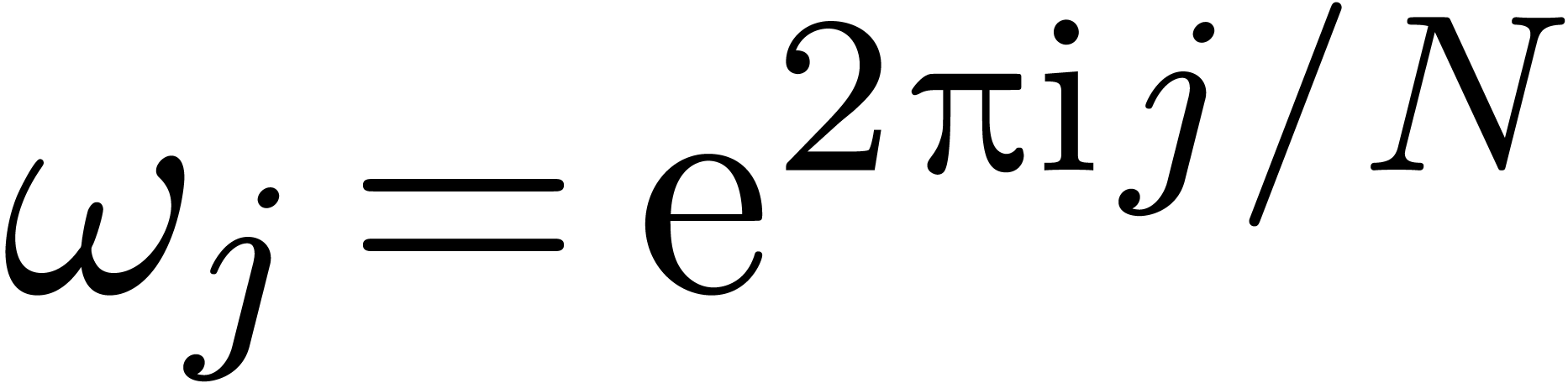

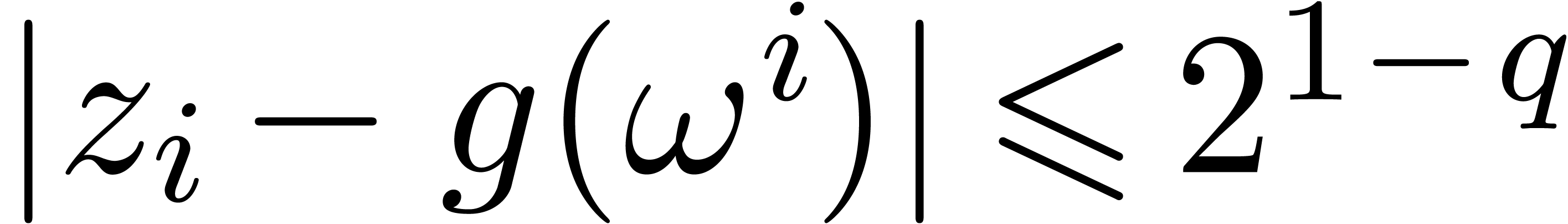

Evaluate  at

at  where

where

, using one direct FFT

for the polynomial

, using one direct FFT

for the polynomial  and

and  scalar inversions.

scalar inversions.

Let  be the polynomial of degree

be the polynomial of degree  we recover when applying the inverse FFT on

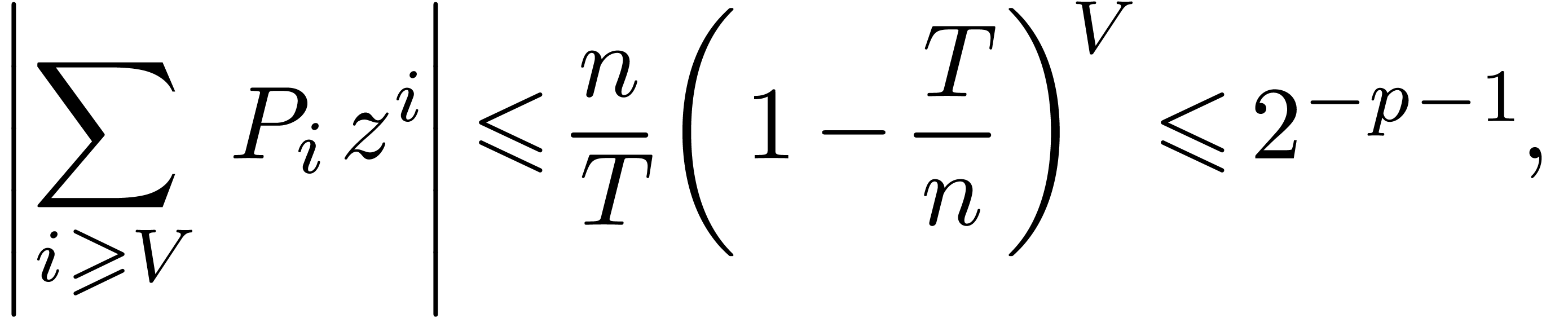

we recover when applying the inverse FFT on  . Then (3) implies

. Then (3) implies

. Consequently,

. Consequently,  .

.

Because of (5) below, we may always take  and

and  , which gives a

complexity bound of the form

, which gives a

complexity bound of the form  .

In fact the FFT of a numeric

.

In fact the FFT of a numeric  -bit

polynomial of degree

-bit

polynomial of degree  can be computed in time

can be computed in time

[Sch82, Section 3], which drops the

bound further down to

[Sch82, Section 3], which drops the

bound further down to  .

.

In practice, we may also start with  and double

and double

until the computed approximation

until the computed approximation  of

of  satisfies the equation

satisfies the equation  up to a sufficient precision. This leads to the same

complexity bound

up to a sufficient precision. This leads to the same

complexity bound  as in the lemma.

as in the lemma.

It is not clear which of the two methods is most efficient: Newton's

method performs a certain amount of recomputations, whereas the

alternative method requires us to work at a sufficiently large degree

for which (3) holds.

for which (3) holds.

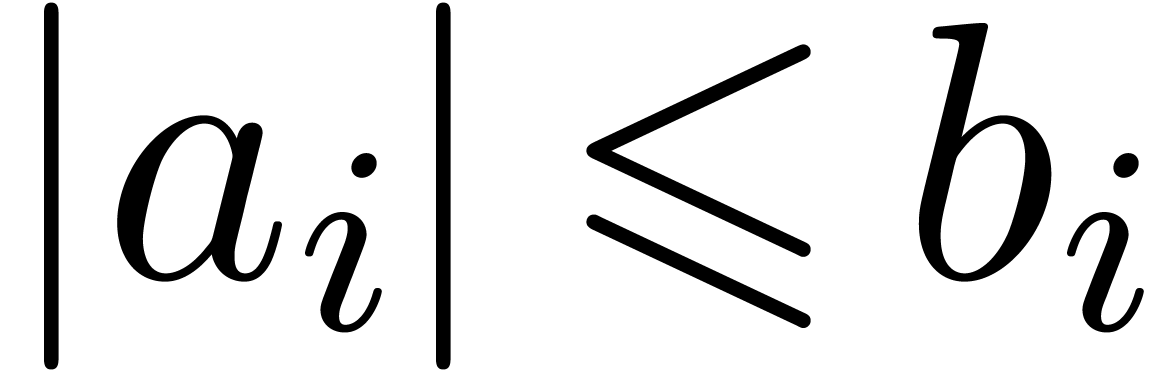

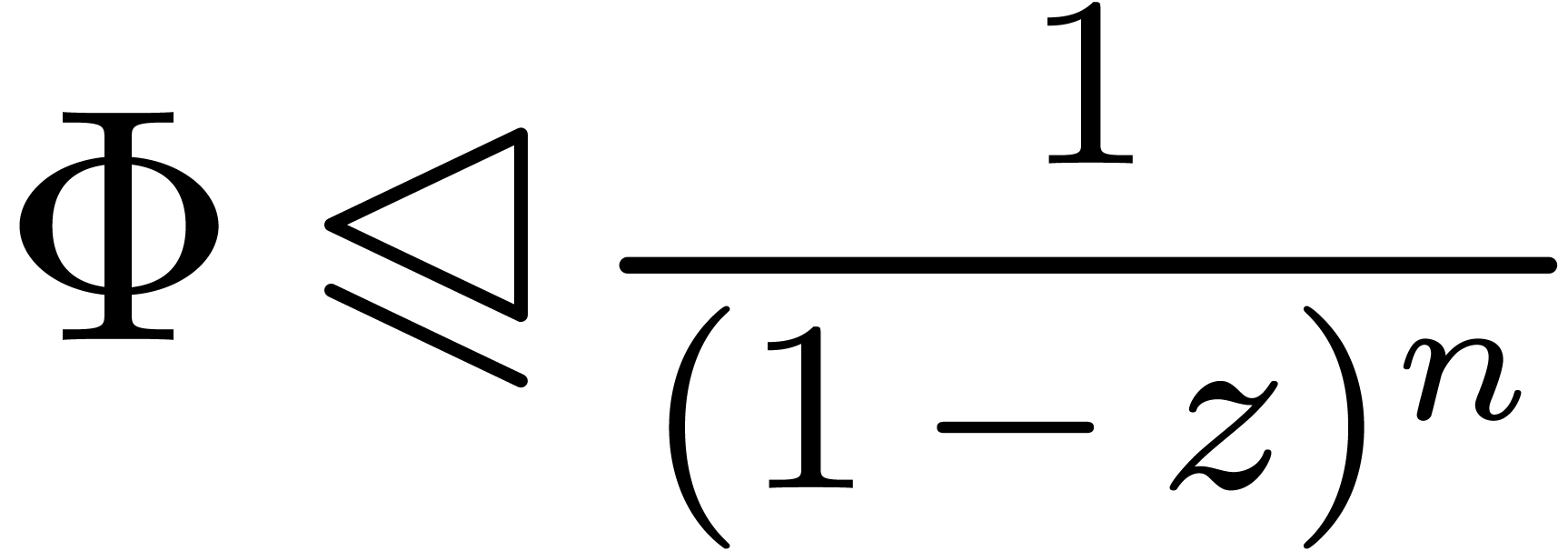

Given power series  and

and  , where

, where  ,

we will say that

,

we will say that  majorates

majorates  and write

and write  if

if  for all coefficients of

for all coefficients of  .

This notation applies in particular to polynomials.

.

This notation applies in particular to polynomials.

and

and  as in lemma 3, we may compute a

as in lemma 3, we may compute a  -approximation

of

-approximation

of  in time

in time  .

.

Proof. Then  and

and  , whence

, whence

We conclude by applying lemma 3 for  and

and  .

.

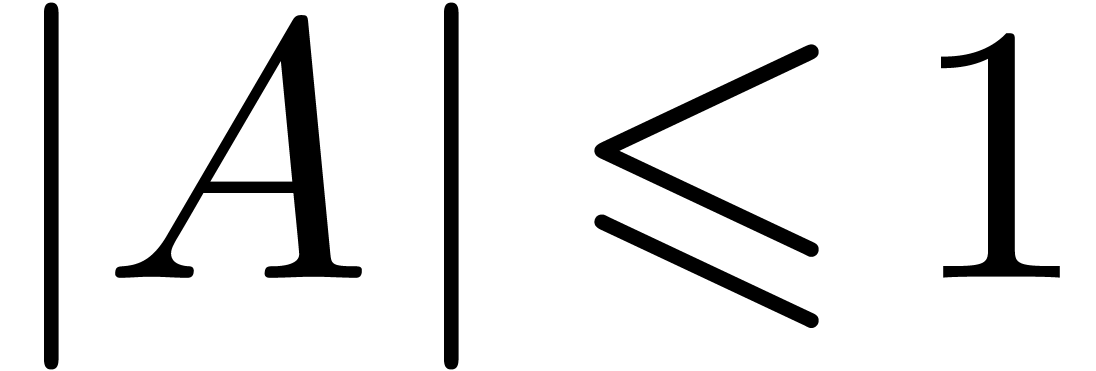

The following result was first proved in [Sch82, Section 4].

be polynomials with

be polynomials with  ,

,  and

and

for  with

with  for all

for all

. Consider the Euclidean

division

. Consider the Euclidean

division

with  . Given

. Given  , we may compute a

, we may compute a  -approximations of

-approximations of  and

and  in time

in time  .

.

Proof. Setting  and

and  , we may write

, we may write

Setting  , we then have

, we then have

Our lemma now follows from lemmas 6 and 1.

Remark  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  , it is again possible to prove the improved

estimate

, it is again possible to prove the improved

estimate  . However, the proof

relies on Schönhage's original method, using the same doubling

strategy as in remark 5. Indeed, when using Newton's method

for inverting

. However, the proof

relies on Schönhage's original method, using the same doubling

strategy as in remark 5. Indeed, when using Newton's method

for inverting  , nice bounds

, nice bounds

and

and  do not necessarily

imply a nice bound for

do not necessarily

imply a nice bound for  ,

where

,

where  is the truncated inverse of

is the truncated inverse of  . Using a relaxed division algorithm [vdH02]

for

. Using a relaxed division algorithm [vdH02]

for  , one may still achieve

the improved bound, up to an additional

, one may still achieve

the improved bound, up to an additional  overhead.

overhead.

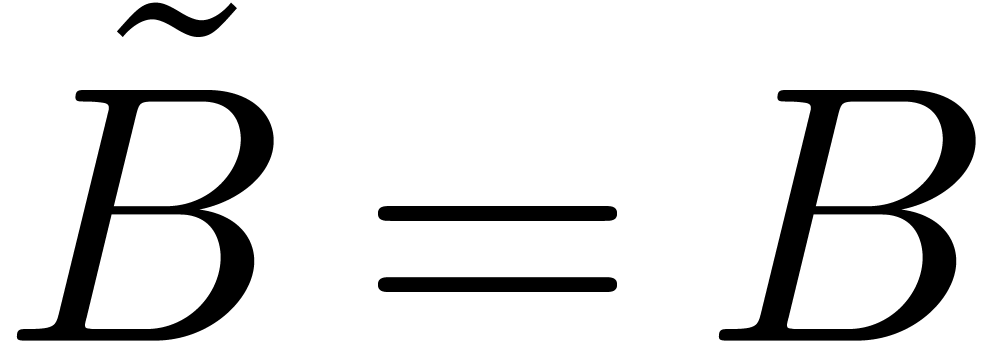

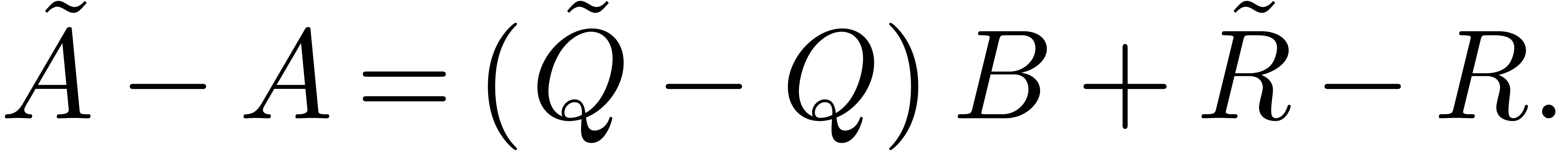

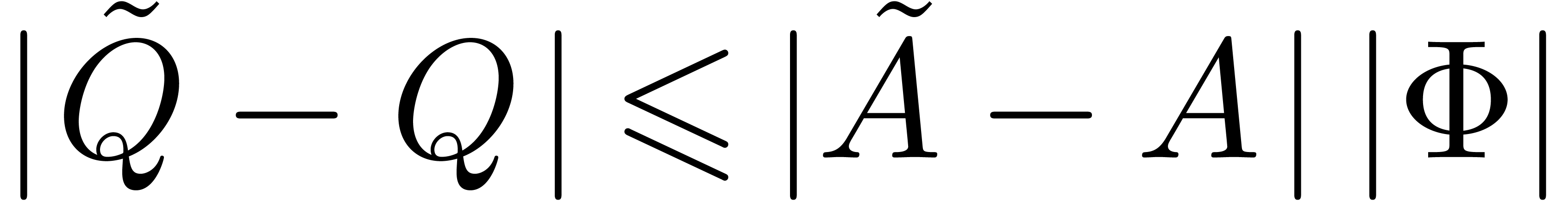

For applications where Euclidean division is used as a subalgorithm, it

is necessary to investigate the effect of small perturbations of the

inputs  and

and  on the

outputs

on the

outputs  and

and  .

.

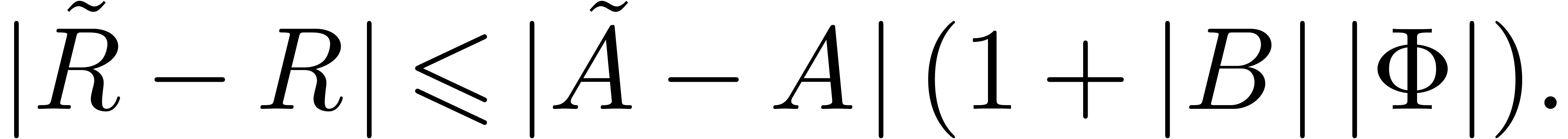

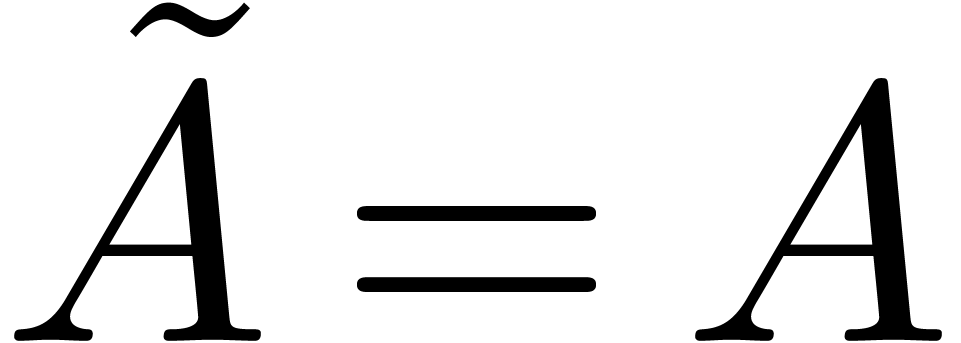

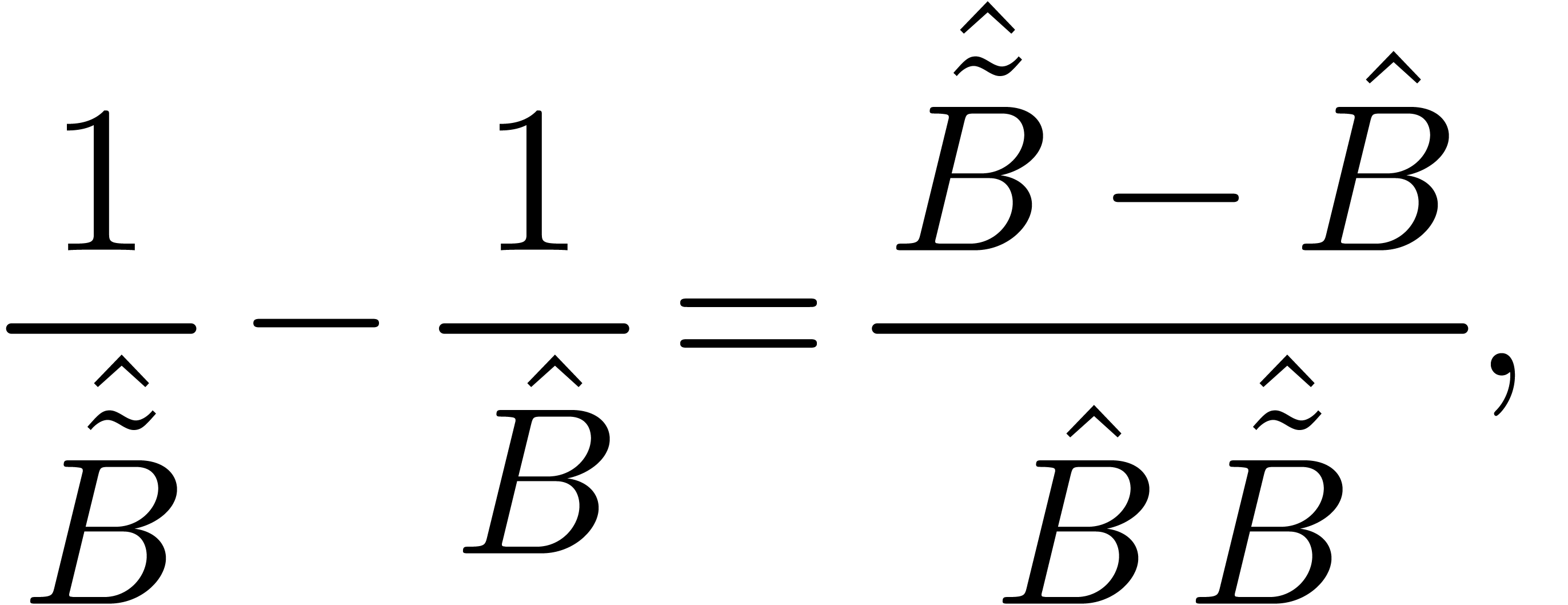

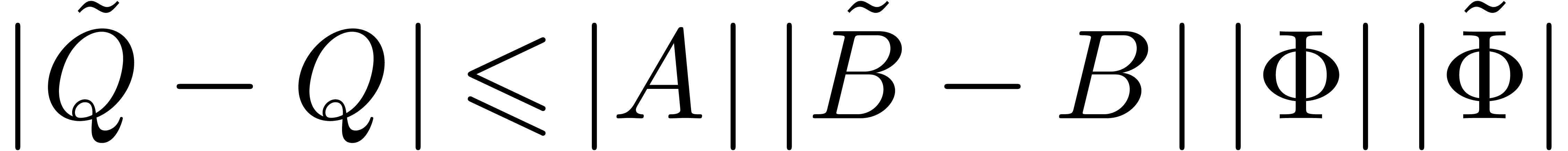

Proof. With the notations of the proof of lemma

7, let  and

and  be the truncations of the power series

be the truncations of the power series  and

and  at order

at order  .

Let us first consider the case when

.

Let us first consider the case when  ,

so that

,

so that

Then  and

and

Let us next consider the case when  .

Then

.

Then

whence  and

and

In general, the successive application of the second and the first case yield

We have also seen in the proof of lemma 6 that  ,

,  and

and  .

.

Proof. With the notations from the proof of lemma 7, we have

whence

and

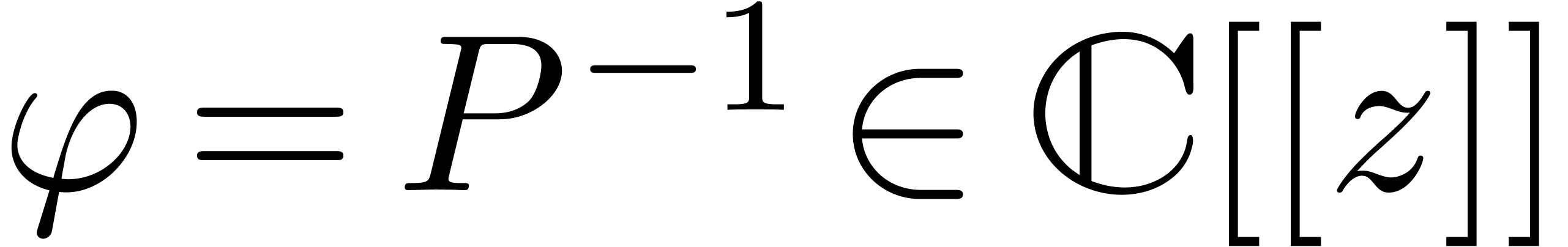

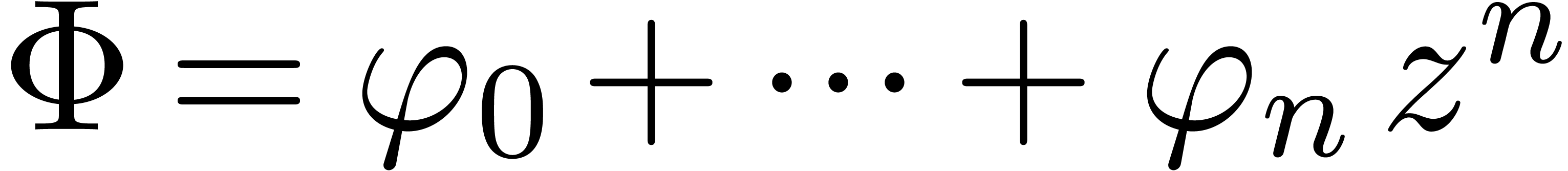

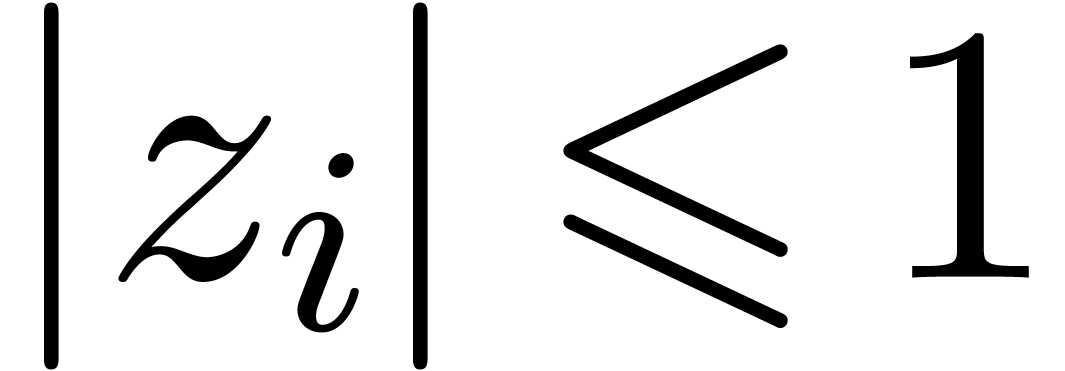

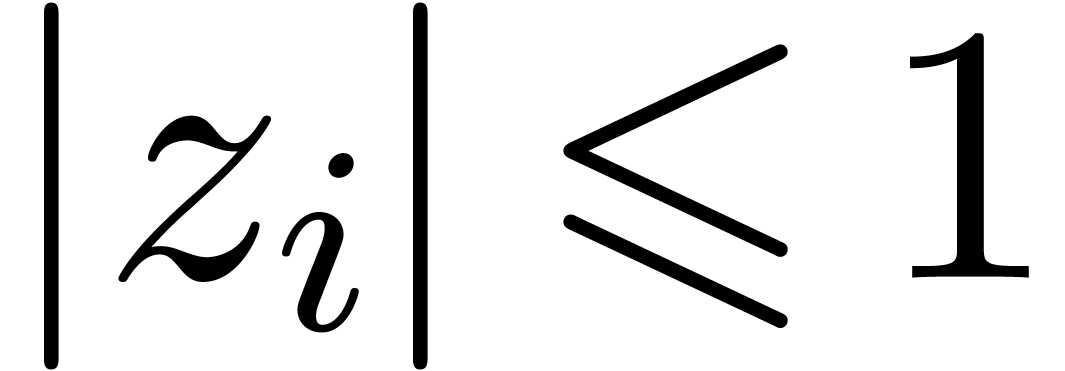

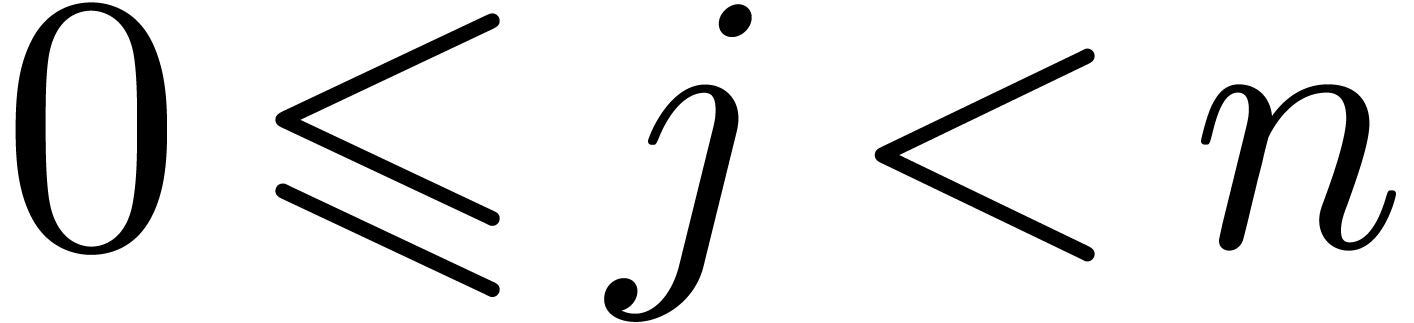

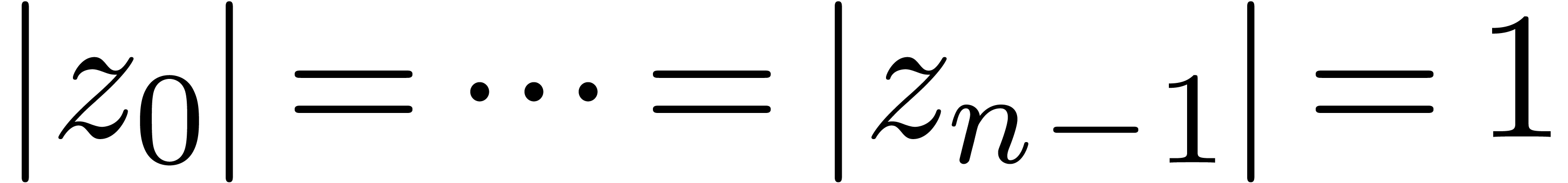

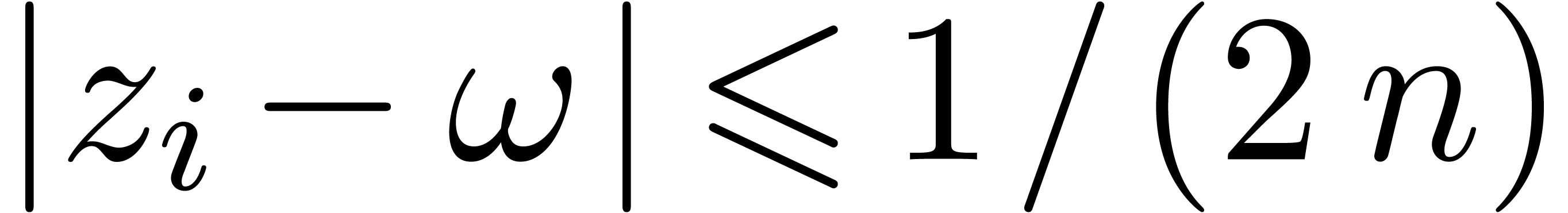

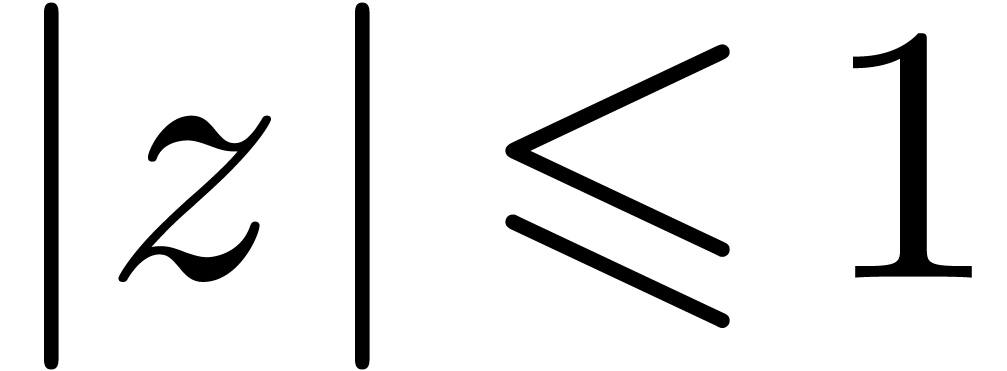

Consider a complex polynomial

which has been normalized so that  .

Let

.

Let

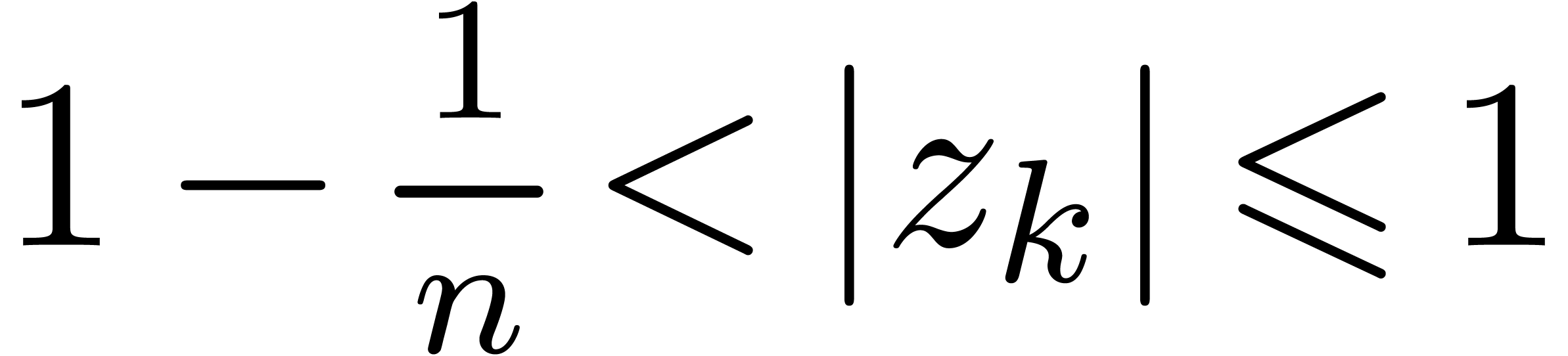

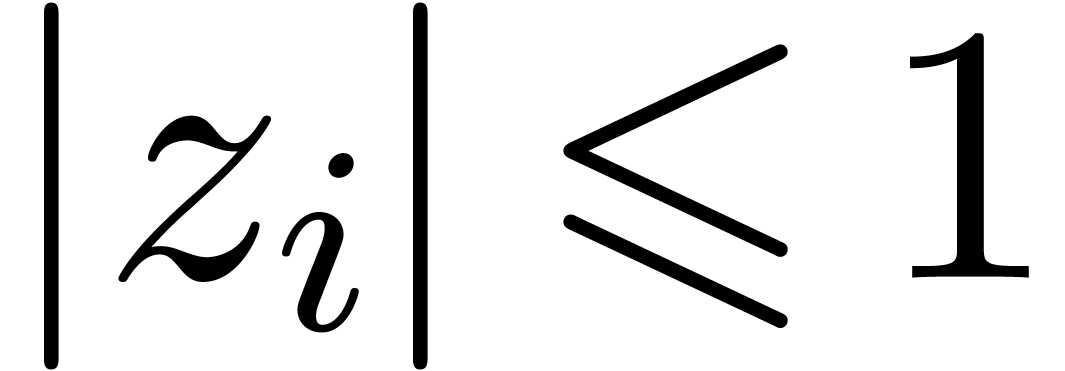

be pairwise distinct points with  for all

for all  . The problem of multi-point

evaluation is to find an efficient algorithm for the simultaneous

evaluations of

. The problem of multi-point

evaluation is to find an efficient algorithm for the simultaneous

evaluations of  at

at  .

A

.

A  -approximation of

-approximation of  will also be called a

will also be called a  -evaluation

of

-evaluation

of  at

at  .

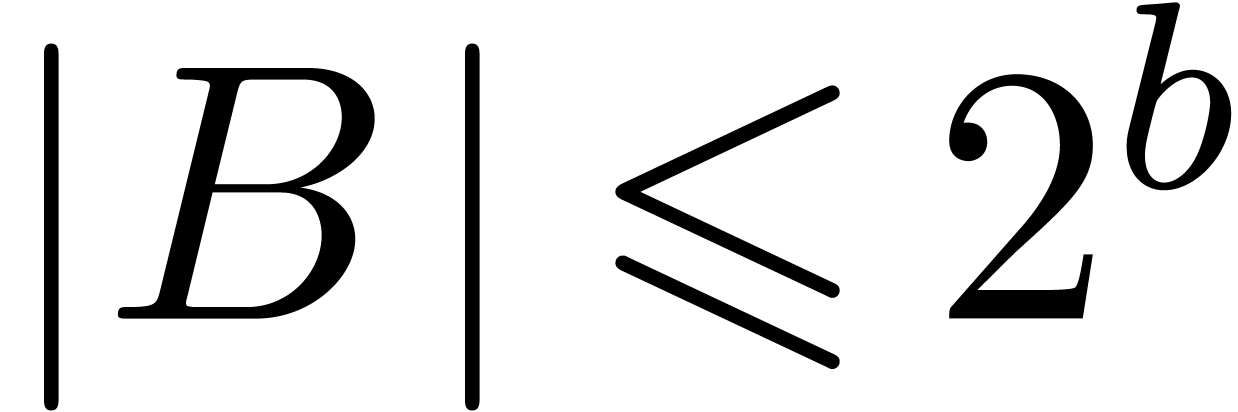

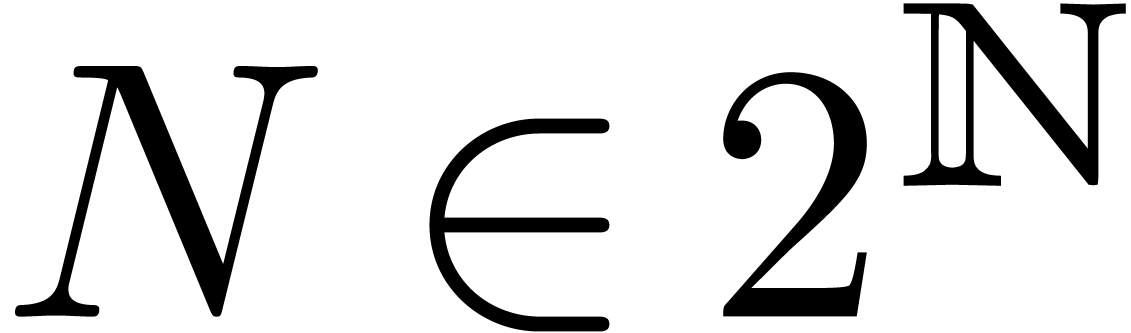

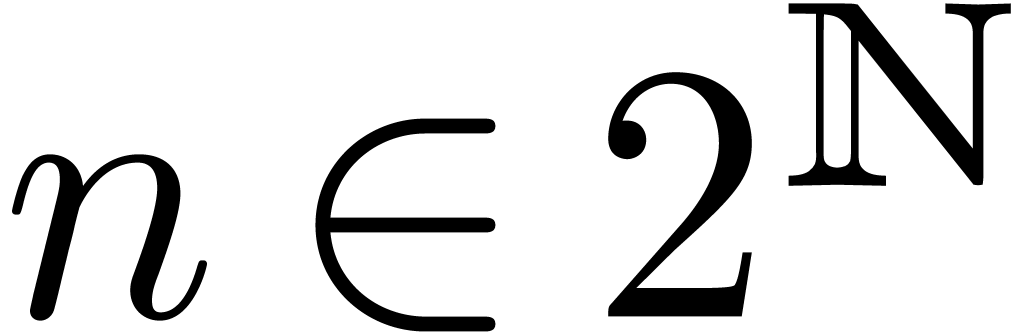

In order to simplify our exposition, we will assume that

.

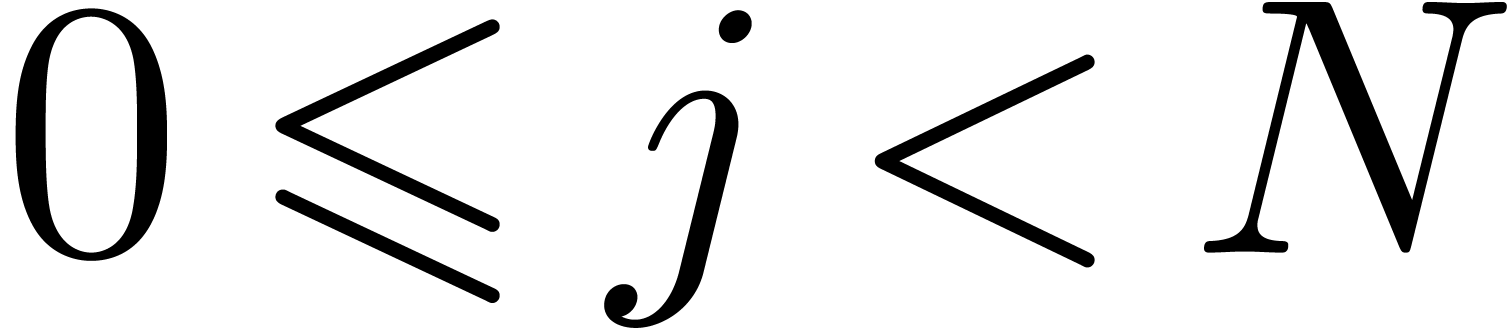

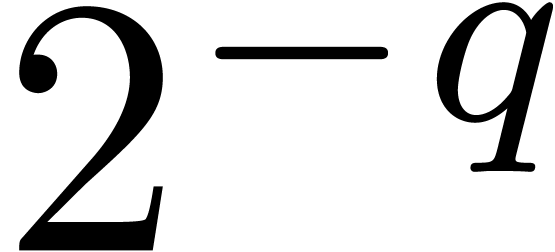

In order to simplify our exposition, we will assume that  is a power of two; this assumption only affects the

complexity analysis by a constant factor.

is a power of two; this assumption only affects the

complexity analysis by a constant factor.

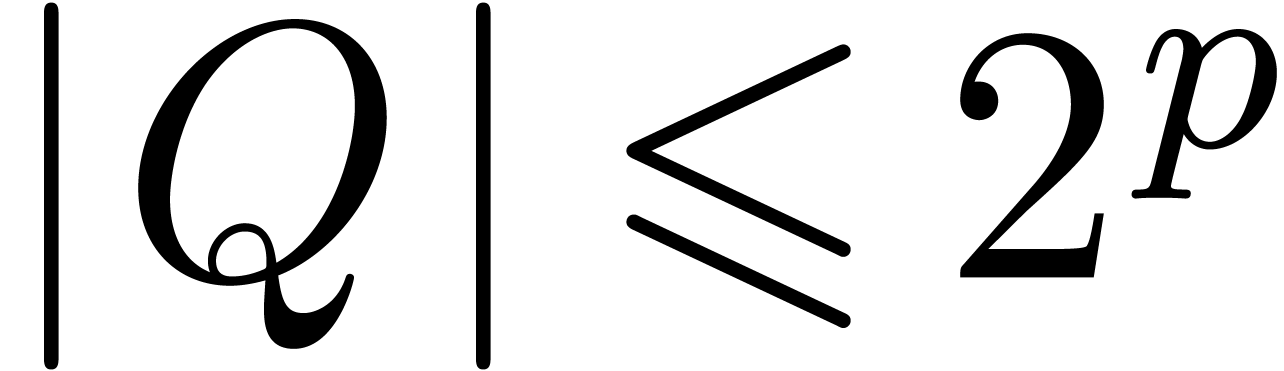

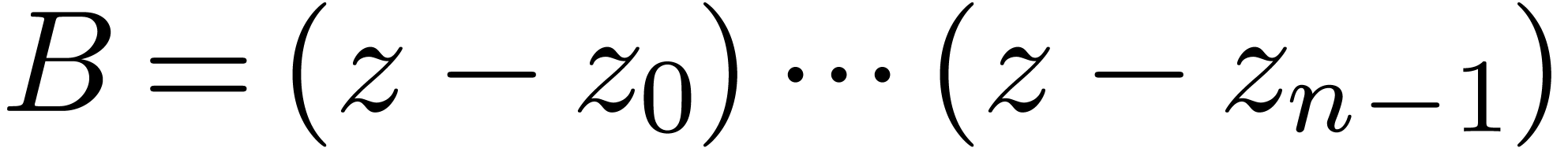

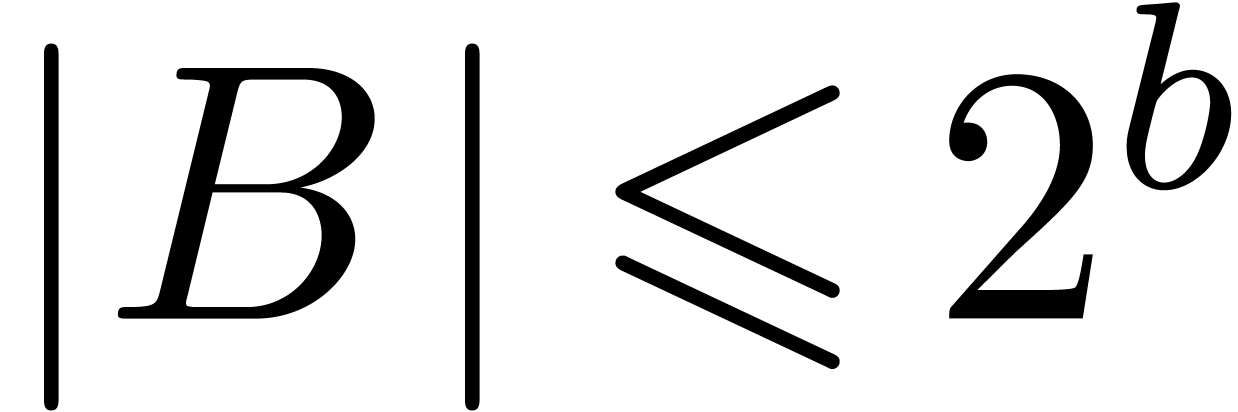

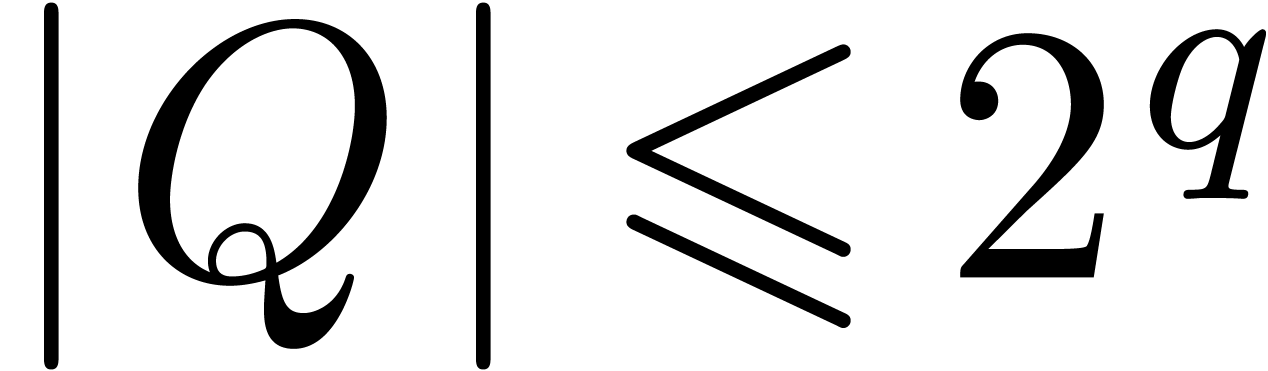

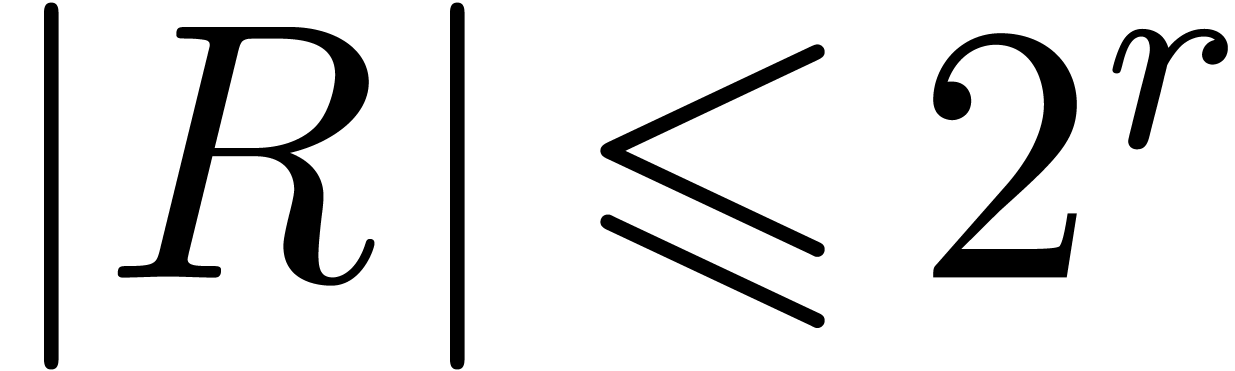

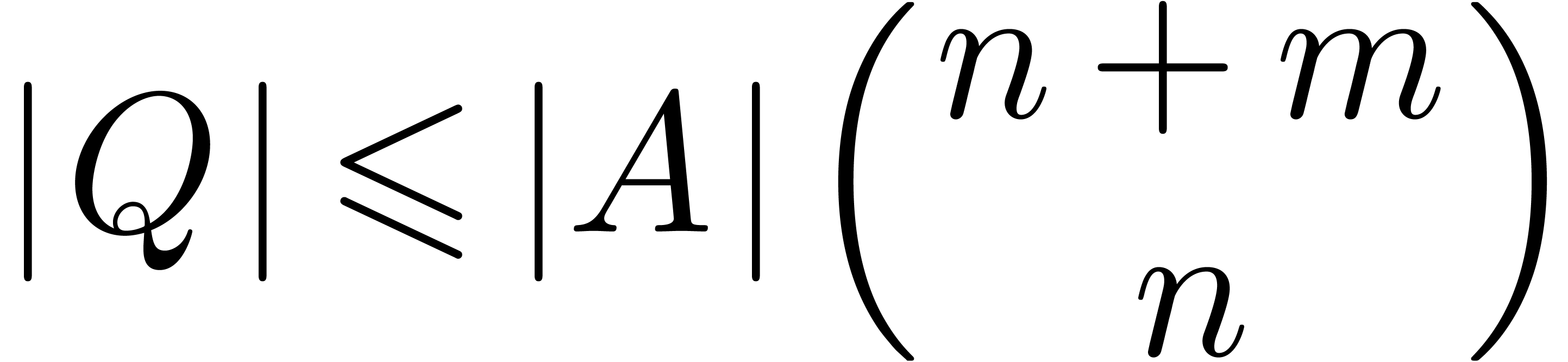

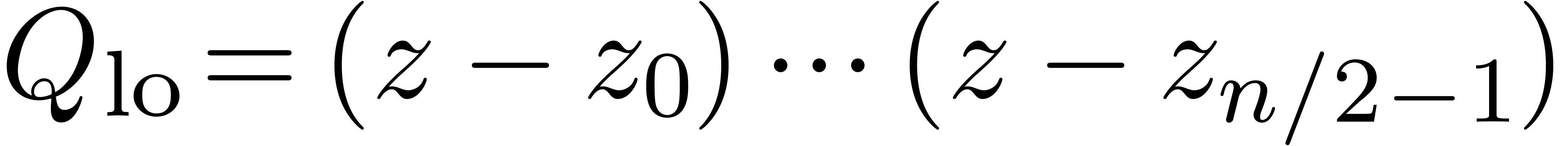

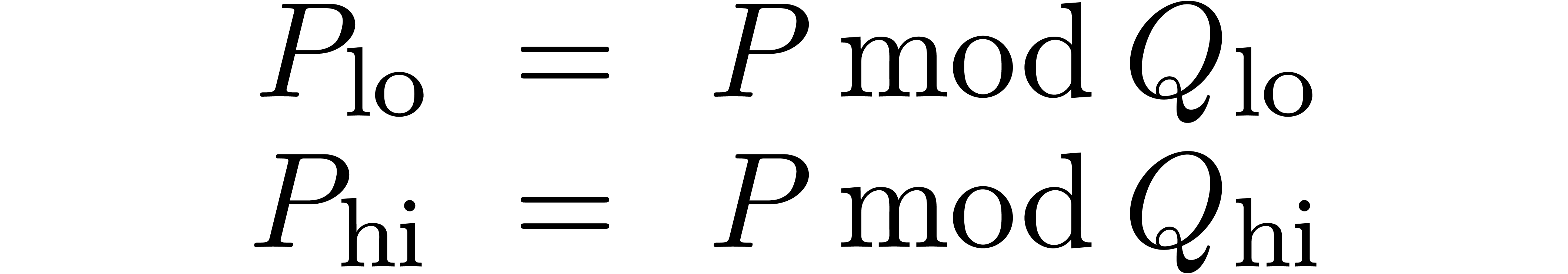

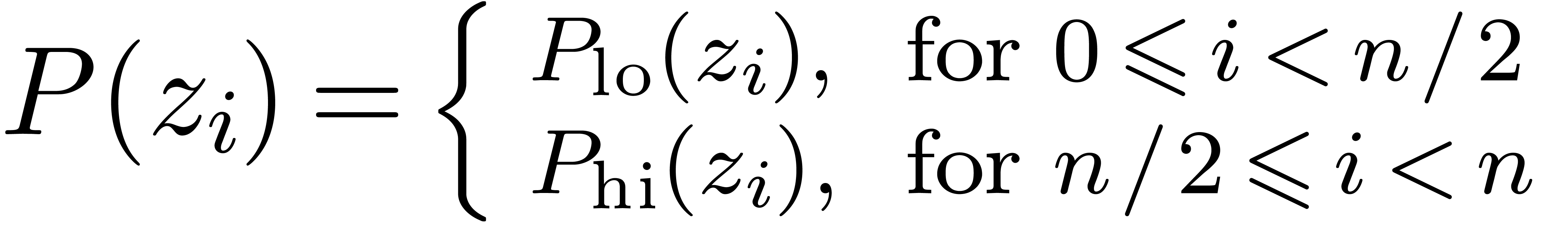

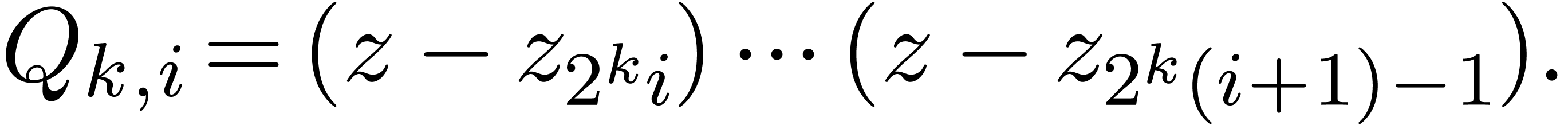

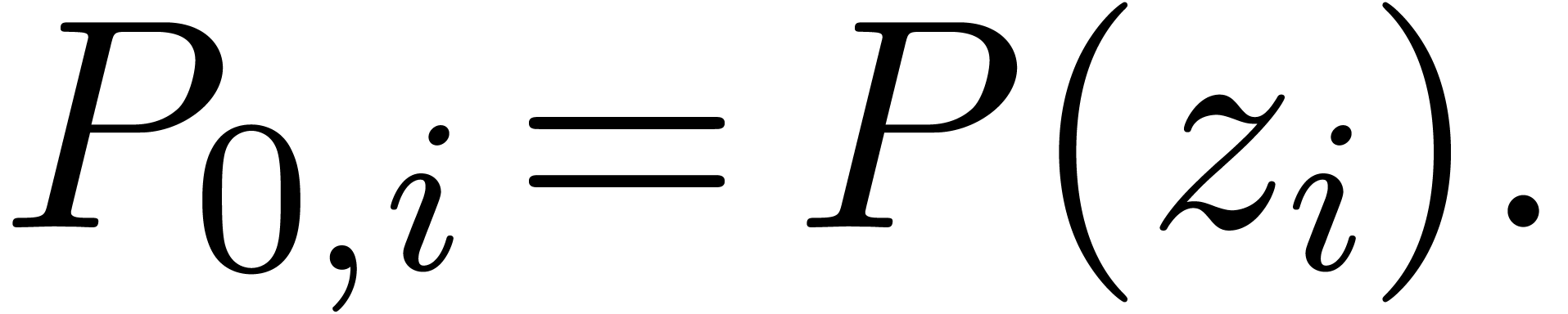

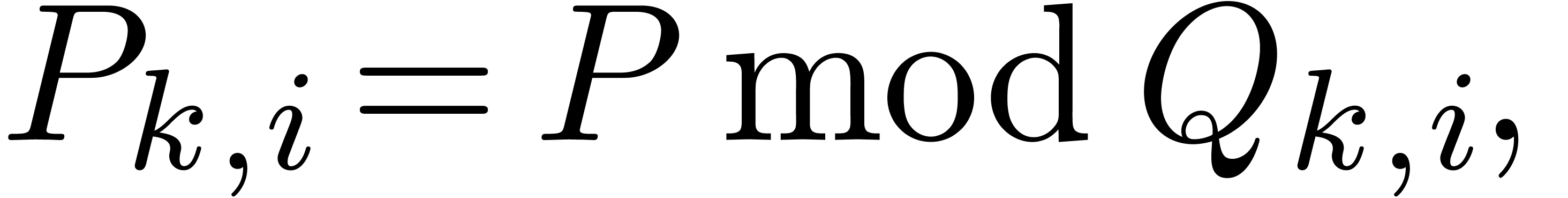

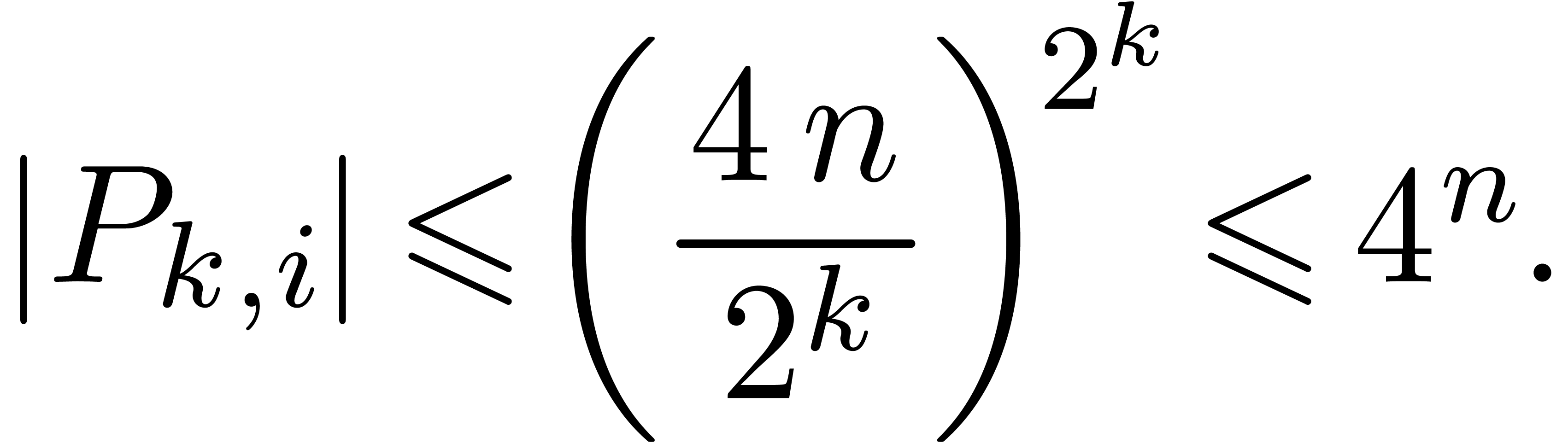

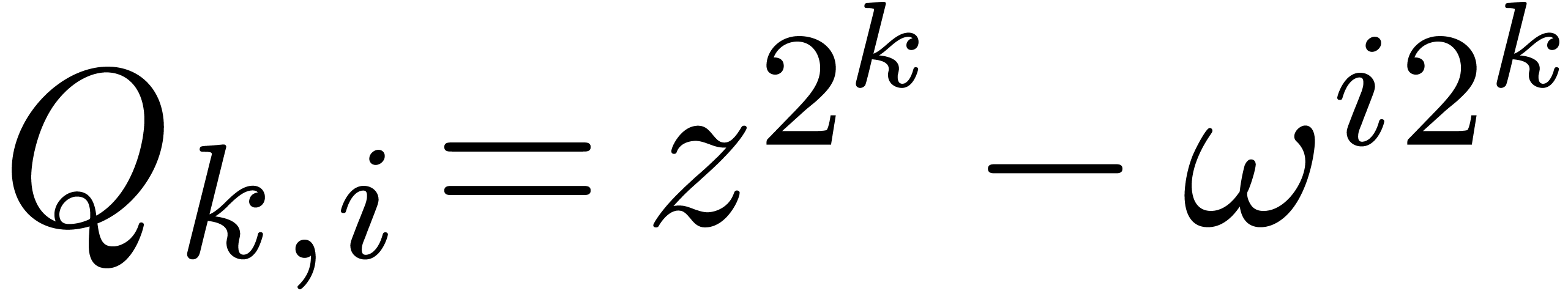

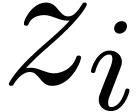

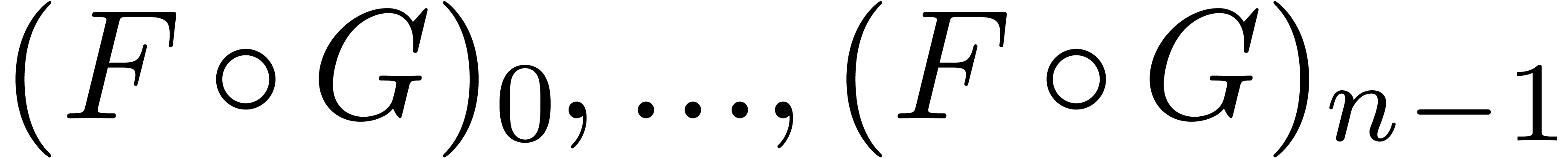

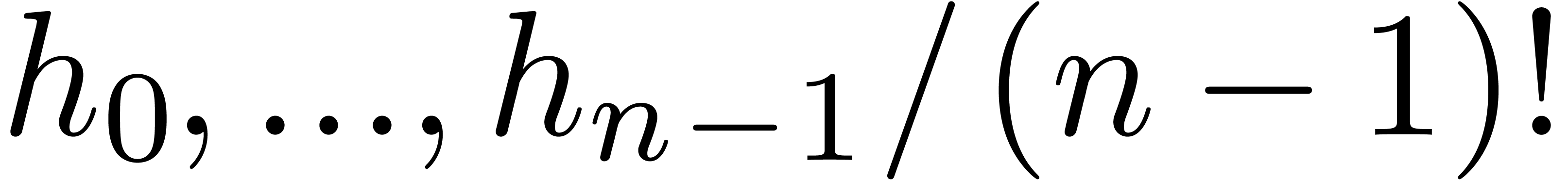

An efficient and classical algorithm for multi-point evaluation [AHU74] relies on binary splitting: let  ,

,  .

Denoting by

.

Denoting by  the remainder of the Euclidean

division of

the remainder of the Euclidean

division of  by

by  ,

we compute

,

we compute

Then

In other words, we have reduced the original problem to two problems of

the same type, but of size  .

.

For the above algorithm to be fast, the partial products  and

and  are also computed using binary

splitting, but in the opposite direction. In order to avoid

recomputations, the partial products are stored in a binary tree of

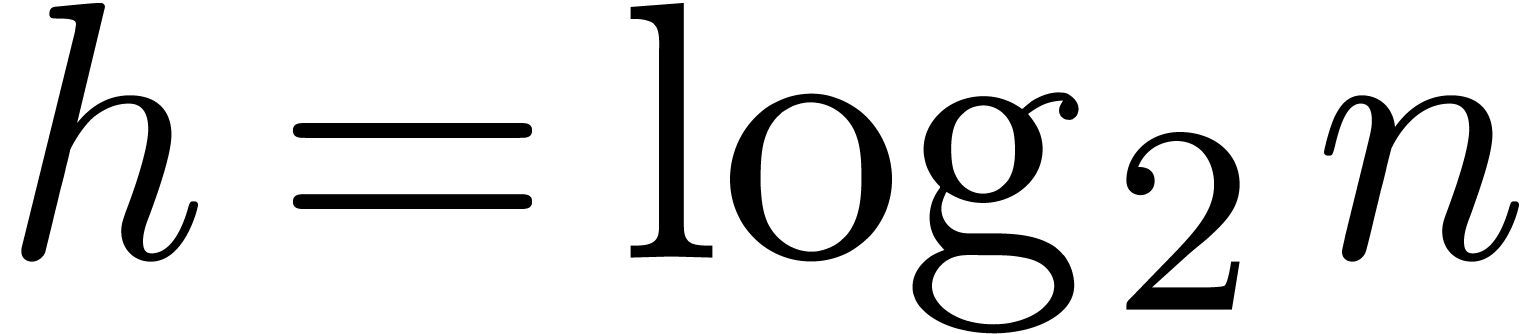

depth

are also computed using binary

splitting, but in the opposite direction. In order to avoid

recomputations, the partial products are stored in a binary tree of

depth  . At depth

. At depth  , we have

, we have  nodes,

labeled by polynomials

nodes,

labeled by polynomials  ,

where

,

where

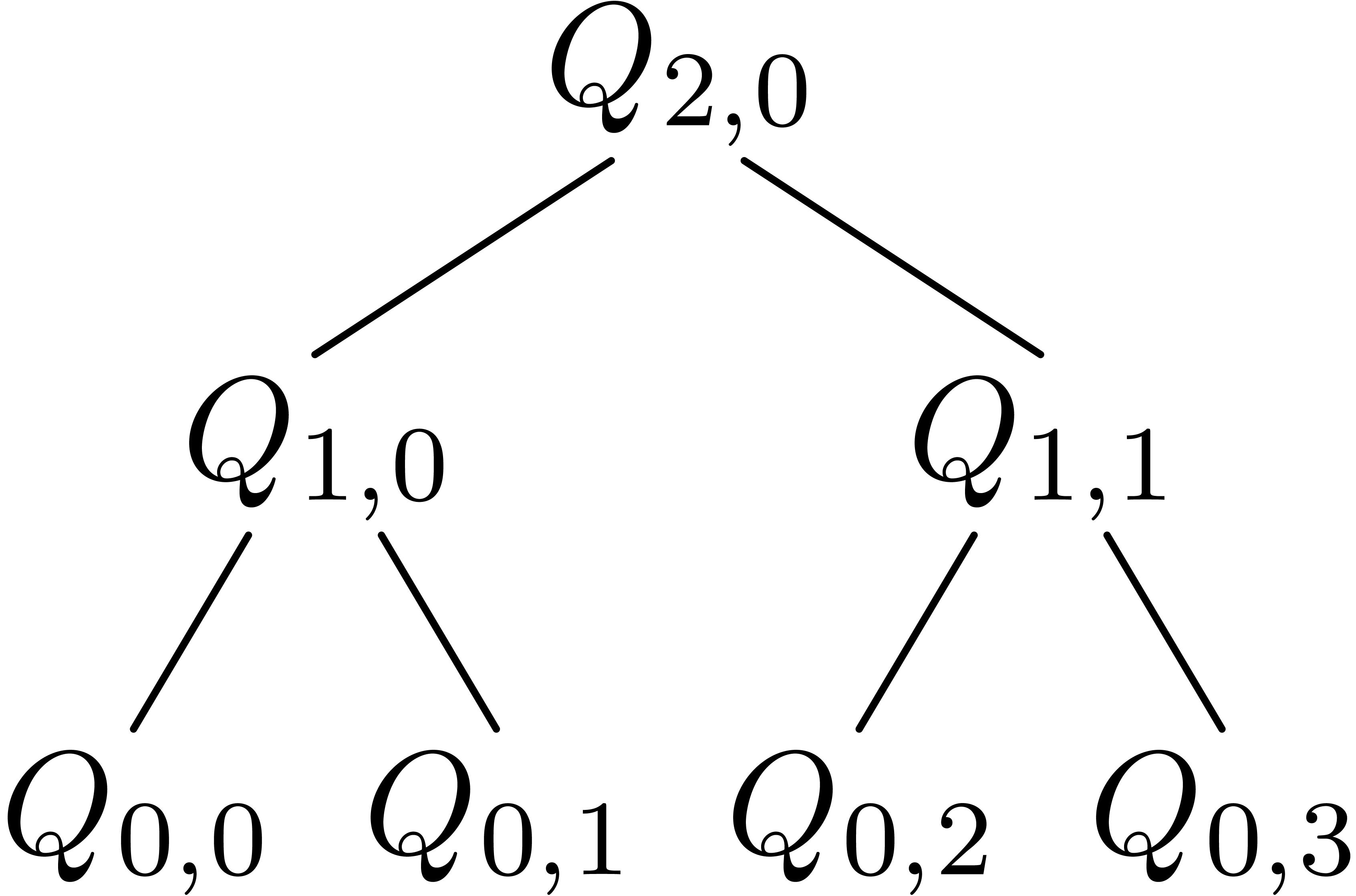

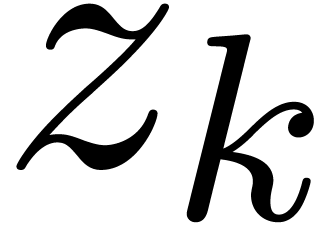

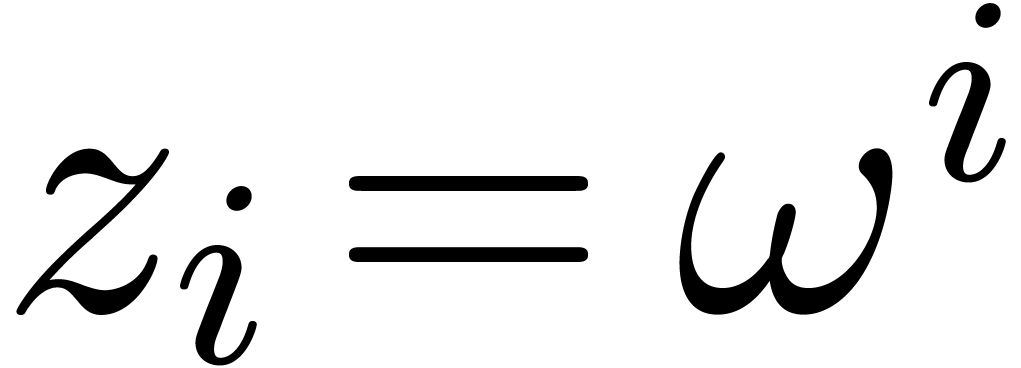

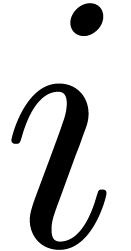

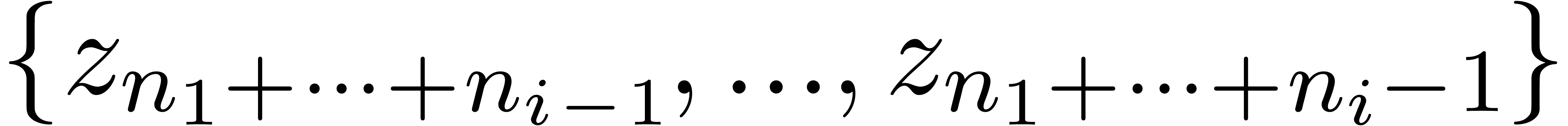

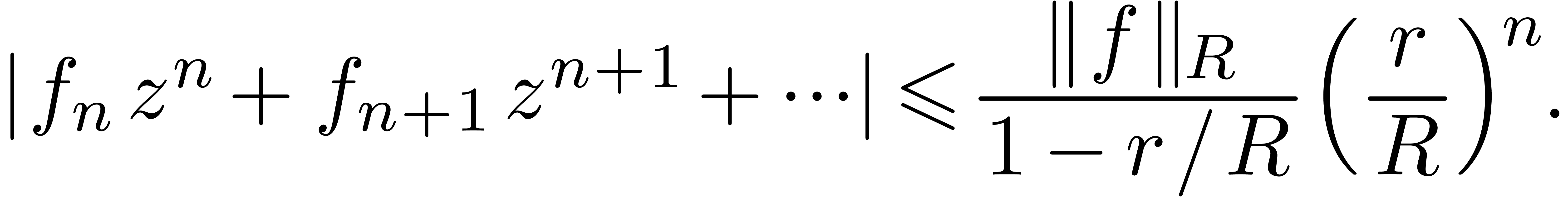

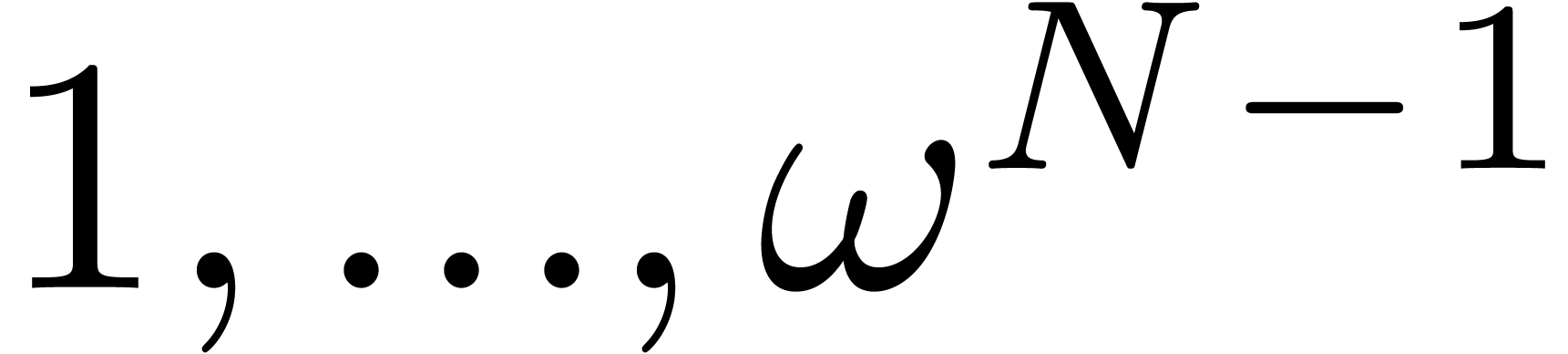

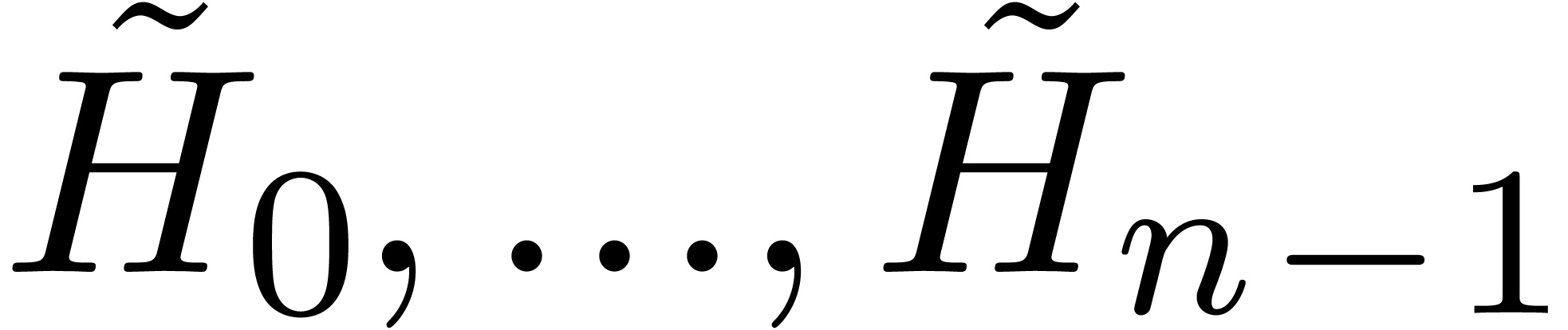

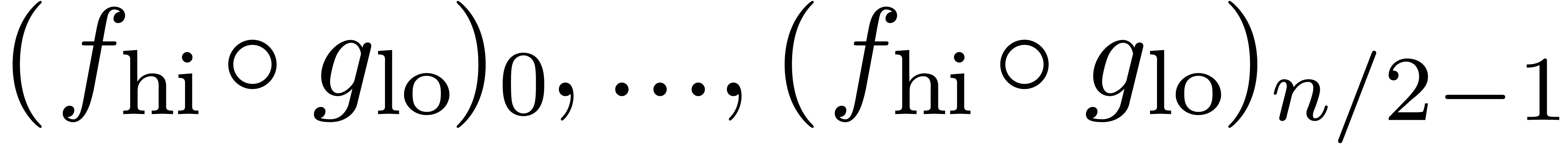

For instance, for  , the tree

is given by

, the tree

is given by

We have

For a given polynomial  of degree

of degree  we may now compute

we may now compute

This second computation can be carried out in place. At the last stage, we obtain

More generally,

|

(8) |

for all  and

and  .

.

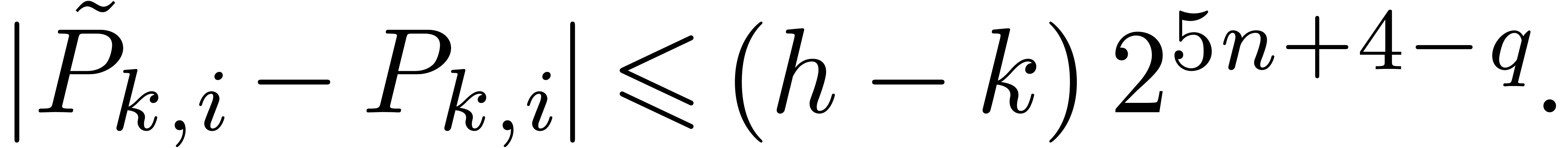

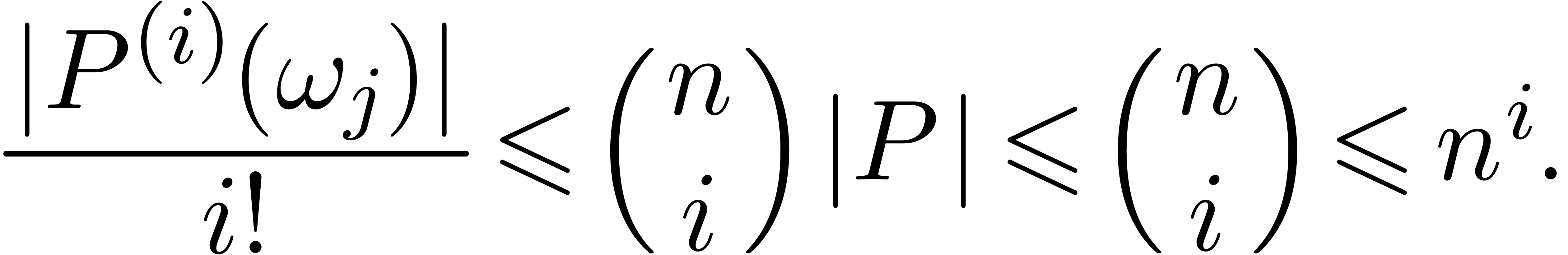

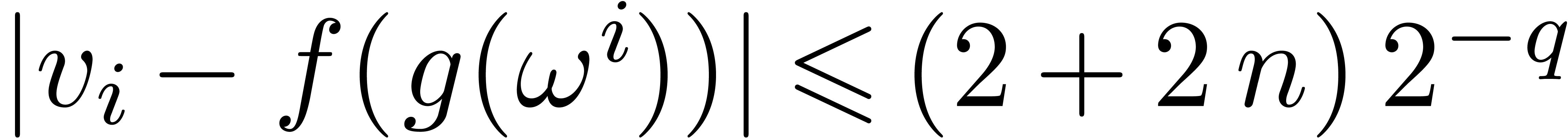

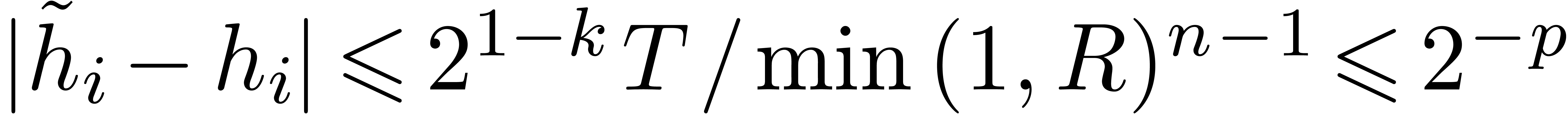

Proof. In the algorithm, let  and assume that all multiplications (6) and all euclidean

divisions (7) are computed up to an absolute error

and assume that all multiplications (6) and all euclidean

divisions (7) are computed up to an absolute error  . Let

. Let  and

and

denote the results of these approximate

computations. We have

denote the results of these approximate

computations. We have

It follows by induction that

From (8) and lemma 10, we have

|

(11) |

In view of (7) and lemma 9, we also have

By induction over  , we obtain

, we obtain

Using our choice of  , we

conclude that

, we

conclude that

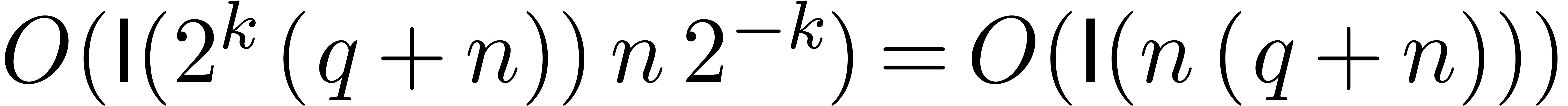

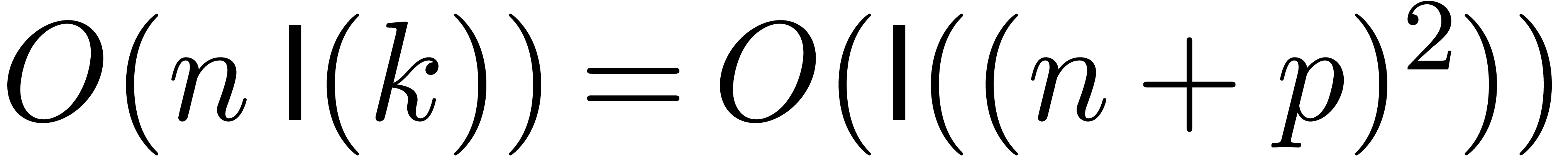

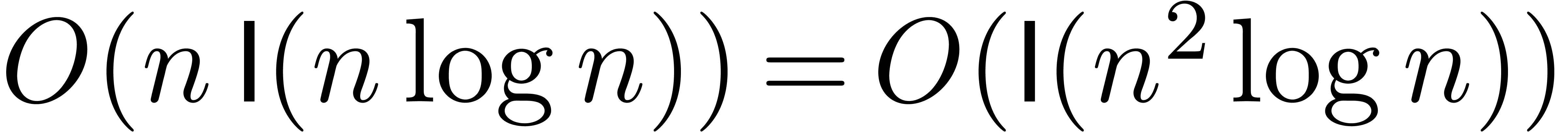

Let us now estimate the complexity of the algorithm. In view of (9) and lemma 1, we may compute  in time

in time  . In view of (11) and lemma 7, the computation of

. In view of (11) and lemma 7, the computation of  takes a time

takes a time  .

For fixed

.

For fixed  , the computation

of all

, the computation

of all  and

and  thus takes a

time

thus takes a

time  . Since there are

. Since there are  stages, the time complexity of the complete algorithm

is bounded by

stages, the time complexity of the complete algorithm

is bounded by  .

.

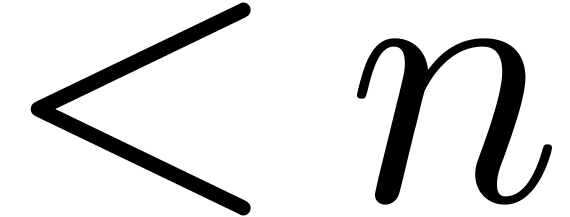

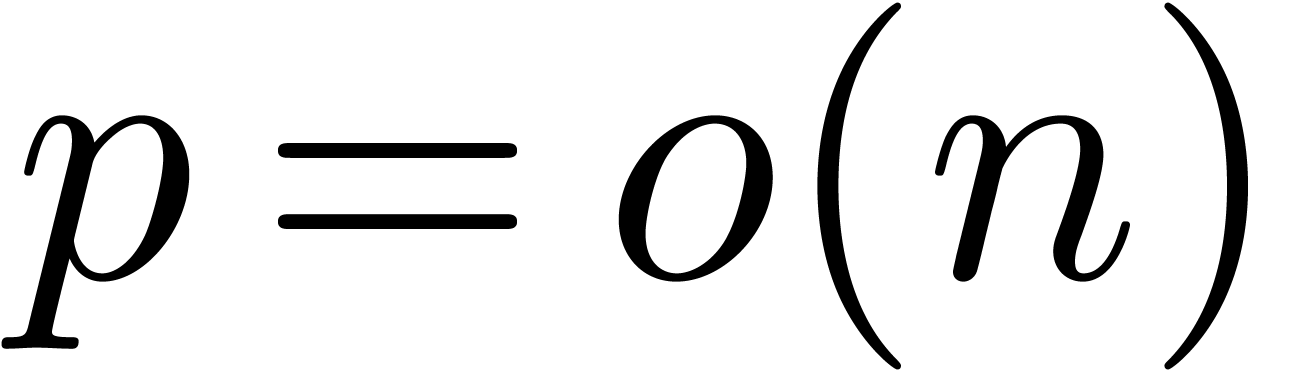

If  , then the bound from

lemma 11 reduces to

, then the bound from

lemma 11 reduces to  ,

which is not very satisfactory. Indeed, in the very special case when

,

which is not very satisfactory. Indeed, in the very special case when

for

for  ,

we may achieve the complexity

,

we may achieve the complexity  ,

by using the fast Fourier transform. In general, we may strive for a

bound of the form

,

by using the fast Fourier transform. In general, we may strive for a

bound of the form  . We have

not yet been able to obtain this complexity, but we will now describe

some partial results in this direction. Throughout the section, we

assume that

. We have

not yet been able to obtain this complexity, but we will now describe

some partial results in this direction. Throughout the section, we

assume that  .

.

. Then we may

. Then we may

-evaluate

-evaluate  at

at  in time

in time  .

.

Proof. Let  ,

,

and

and  for all

for all  . Each of the points

. Each of the points  is

at the distance of at most

is

at the distance of at most  to one of the points

to one of the points

. We will compute

. We will compute  using a Taylor series expansion of

using a Taylor series expansion of  at

at  . We first observe that

. We first observe that

|

(12) |

Using  fast Fourier transforms of size

fast Fourier transforms of size  , we first compute

, we first compute  -approximations of

-approximations of  for

all

for

all  and

and  .

This can be done in time

.

This can be done in time

From (12) it follows that

The  -evaluation of

-evaluation of  sums of the form

sums of the form  using Horner's

rule takes a time

using Horner's

rule takes a time  .

.

-evaluate

-evaluate  at

at  in time

in time  .

.

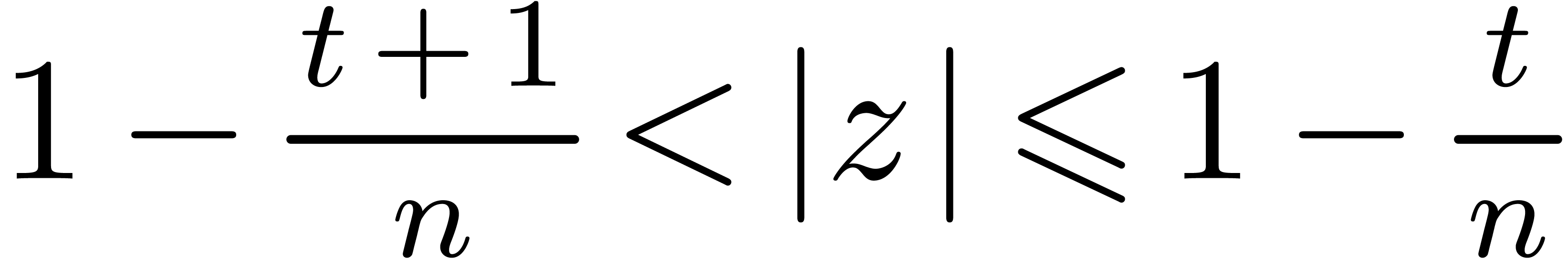

Proof. The proof of the above proposition adapts

to the case when  for all

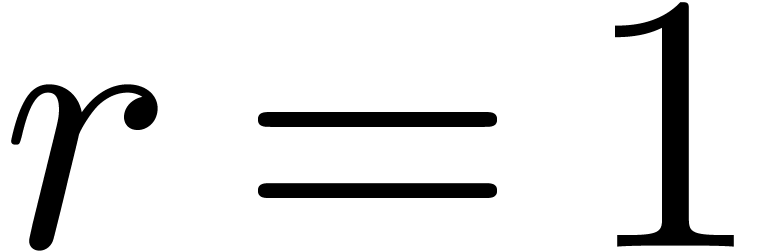

for all  . Let us now subdivide the unit disk into

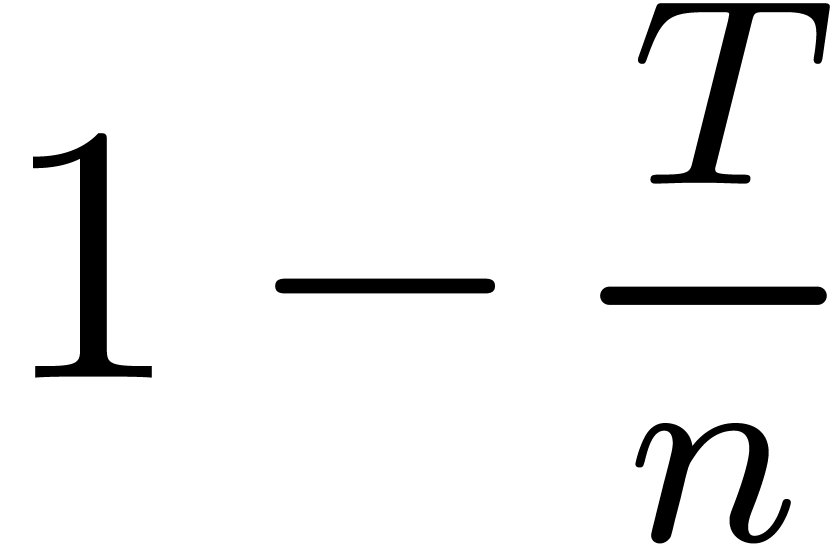

. Let us now subdivide the unit disk into  annuli

annuli  and the disk of radius

and the disk of radius

. For a fixed annulus, we may

evaluate

. For a fixed annulus, we may

evaluate  at each of the

at each of the  inside the annulus in time

inside the annulus in time  .

For

.

For  , we have

, we have

provided that  . Consequently,

taking

. Consequently,

taking  , we may evaluate

, we may evaluate  at the remaining points in time

at the remaining points in time  . Under the condition

. Under the condition  , and up to logarithmic terms, the sum

, and up to logarithmic terms, the sum

becomes minimal for  and

and  .

.

with

with  and

and  for all

for all  .

Then we may

.

Then we may  -evaluate

-evaluate  at

at  in time

in time  .

.

Proof. We will only provide a sketch of the

proof. As in the proof of proposition 12, we first compute

the Taylor series expansion of  at

at  up to order

up to order  .

This task can be performed in time

.

This task can be performed in time  via a

division of

via a

division of  by

by  followed

by a Taylor shift. We next evaluate this expansion at

followed

by a Taylor shift. We next evaluate this expansion at  for all

for all  . According to

proposition 16, this can be done in time

. According to

proposition 16, this can be done in time  .

.

be a fixed constant. With the

notations of proposition 11, assume that

be a fixed constant. With the

notations of proposition 11, assume that  for all

for all  . Then we may

. Then we may  -evaluate

-evaluate  at

at  in time

in time  .

.

Proof. Again, we will only provide a sketch of

the proof. The main idea is to use the binary splitting algorithm from

the previous subsection. Let  .

If

.

If  for all

for all  ,

then we obtain

,

then we obtain  and the algorithm reduces to a

fast Fourier transform. If each

and the algorithm reduces to a

fast Fourier transform. If each  is a slight

perturbation of

is a slight

perturbation of  , then

, then  becomes a slight perturbation of

becomes a slight perturbation of  . In particular, the Taylor coefficients

. In particular, the Taylor coefficients  of

of  only have a polynomial

growth

only have a polynomial

growth  in

in  .

Consequently, the Euclidean division by

.

Consequently, the Euclidean division by  accounts

for a loss of at most

accounts

for a loss of at most  instead of

instead of  bits of precision. The binary splitting algorithm can

therefore be carried out using a fixed precision of

bits of precision. The binary splitting algorithm can

therefore be carried out using a fixed precision of  bits.

bits.

Sometimes, it is possible to decompose  ,

such that a fast multi-point evaluation algorithm is available for each

set of points

,

such that a fast multi-point evaluation algorithm is available for each

set of points  . This leads to

the question of evaluating

. This leads to

the question of evaluating  at

at  points.

points.

and

and  be such that

be such that  ,

,  and

and  for all

for all  . Let

. Let  be the time

needed in order to compute

be the time

needed in order to compute  -evaluations

of polynomials

-evaluations

of polynomials  with

with  at

at

. Then

. Then  -evaluations of

-evaluations of  at

at

can be computed in time

can be computed in time  .

.

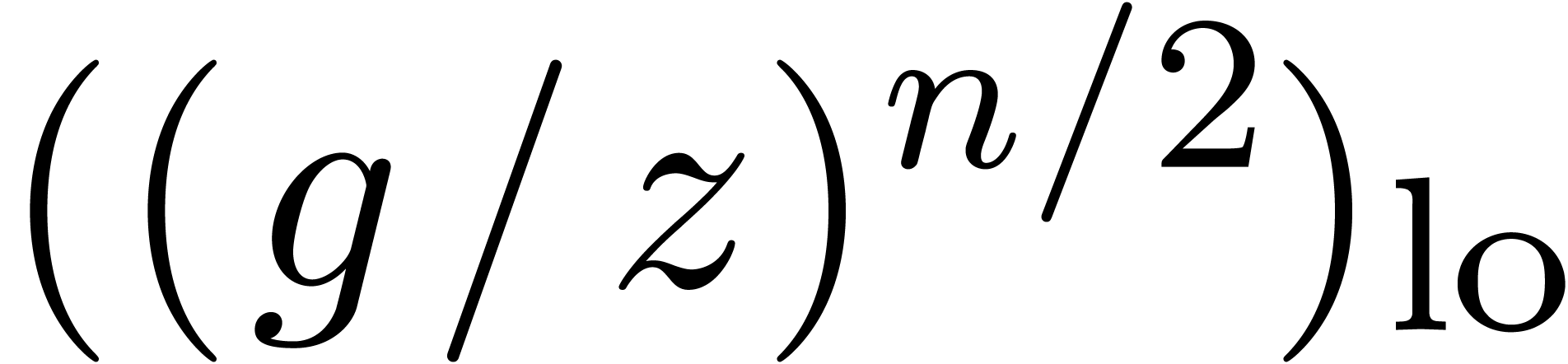

Proof. Without loss of generality, we may assume

that  and

and  are powers of

two. We decompose

are powers of

two. We decompose  as follows:

as follows:

We may compute  -evaluations

of the

-evaluations

of the  at

at  in time

in time  . We may also

. We may also  -approximate

-approximate  in time

in time

, using binary powering.

Using Horner's rule, we may finally

, using binary powering.

Using Horner's rule, we may finally  -evaluate

-evaluate

for  in time

in time  .

.

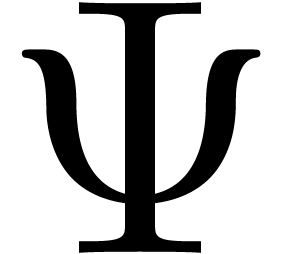

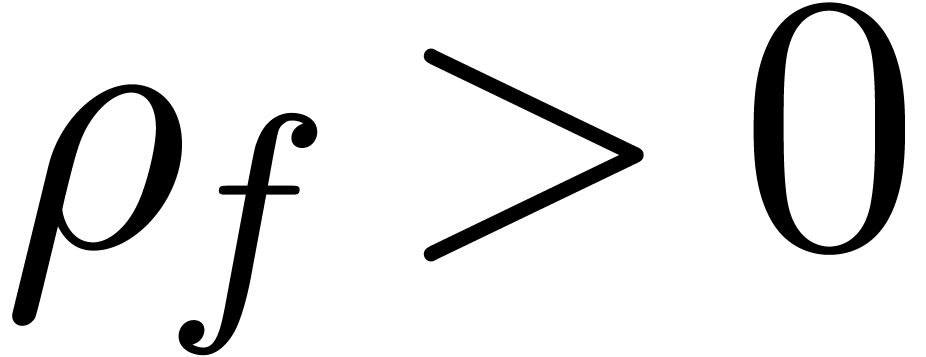

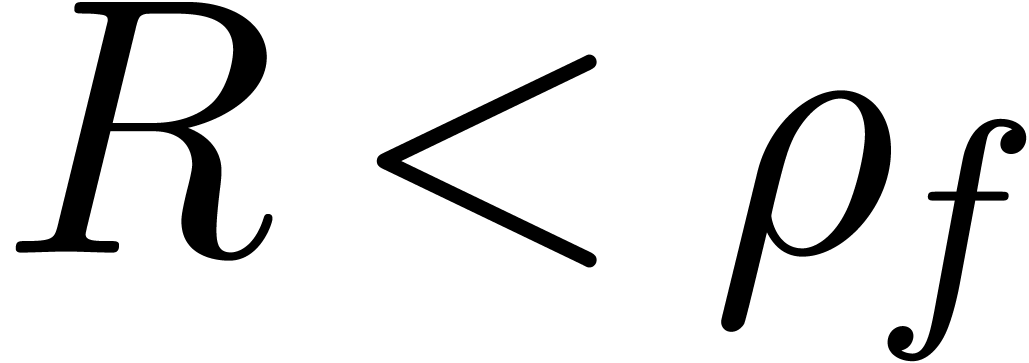

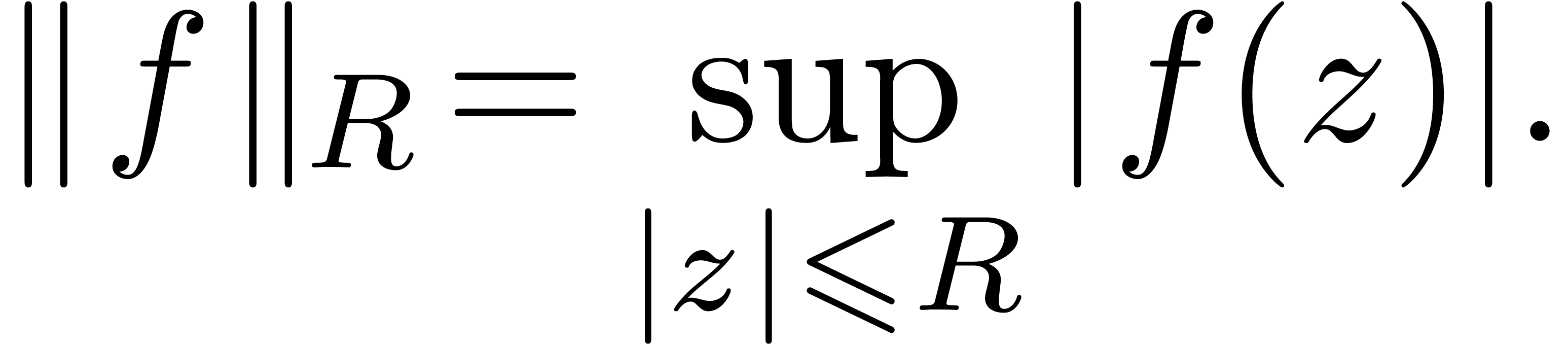

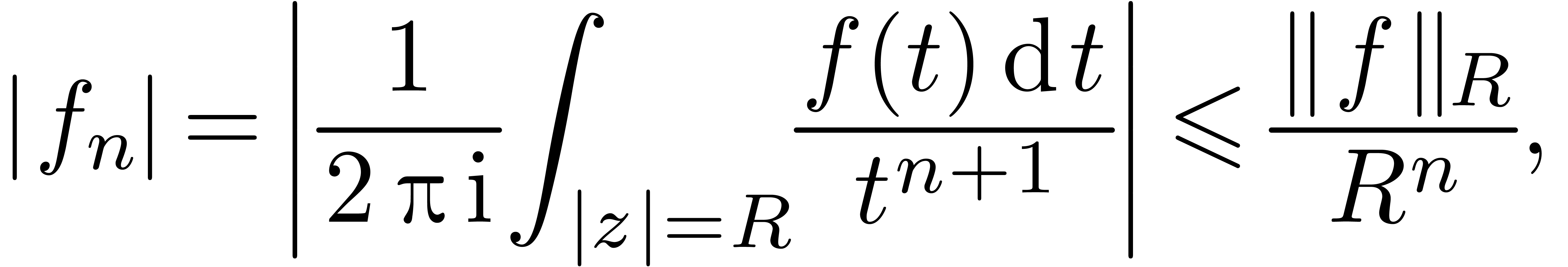

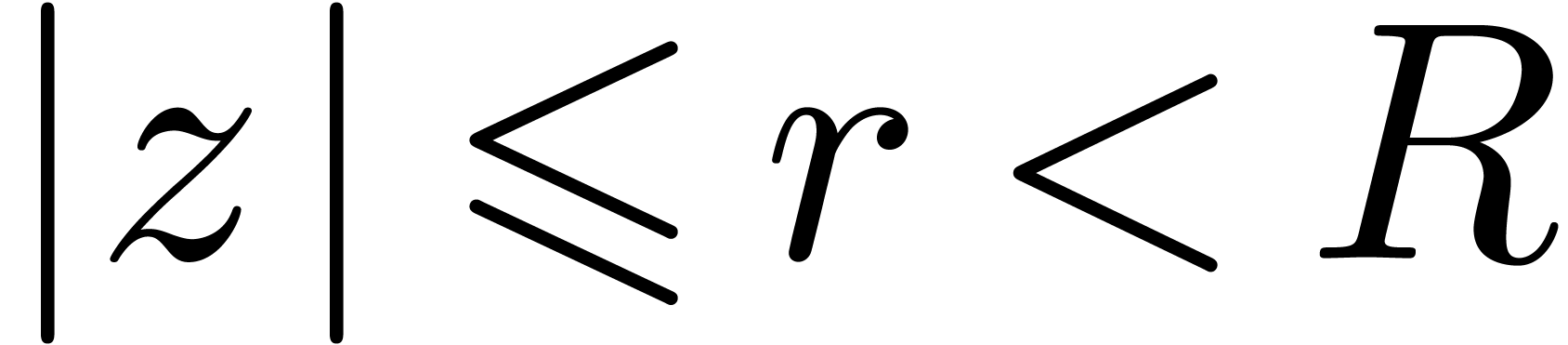

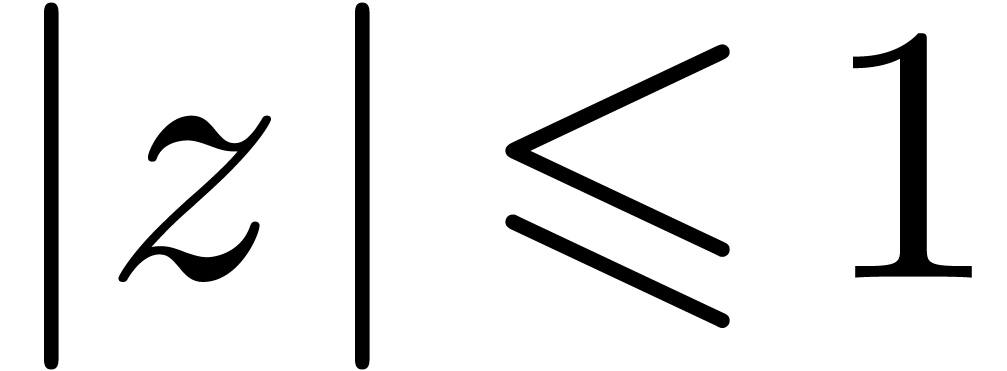

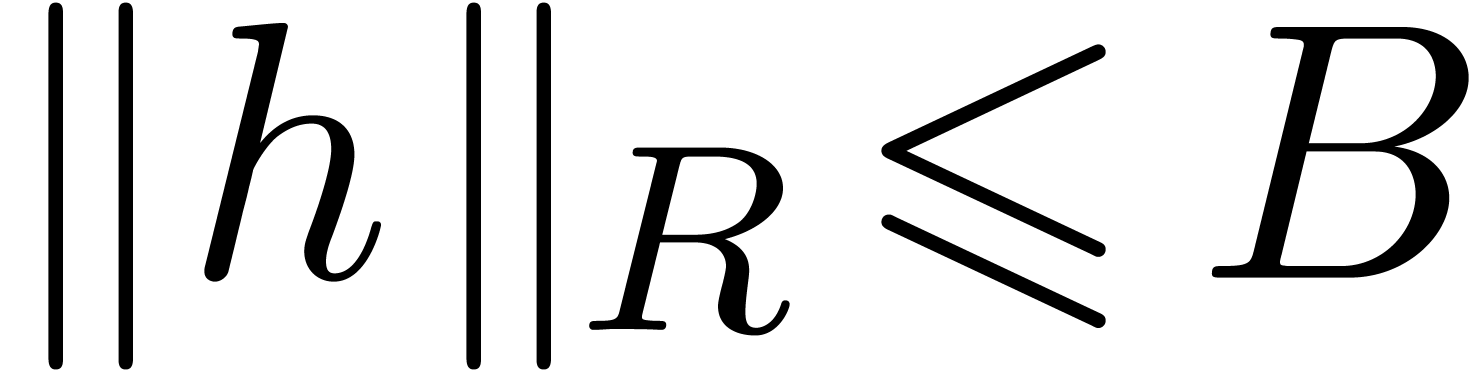

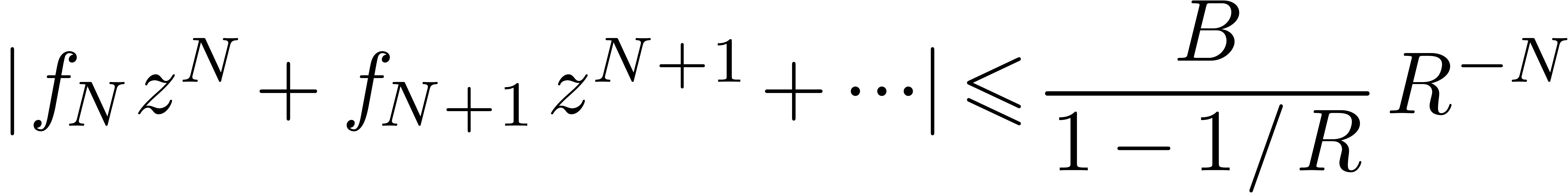

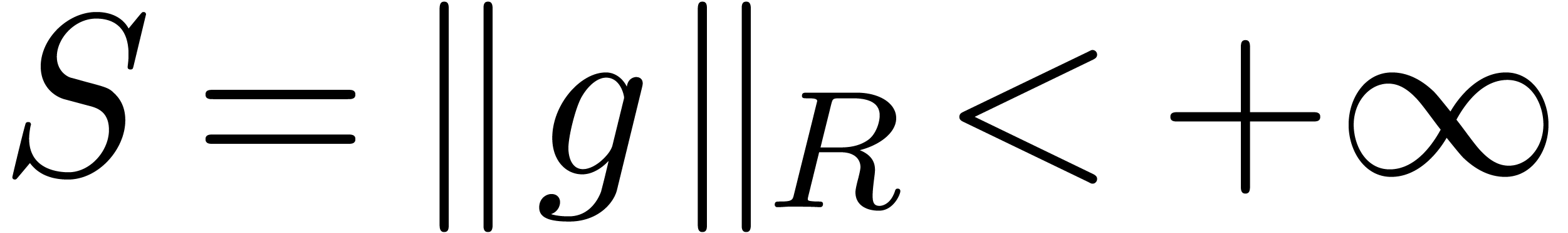

Let  be a convergent power series with radius of

convergence

be a convergent power series with radius of

convergence  . Given

. Given  , we denote

, we denote

Using Cauchy's formula, we have

|

(13) |

For  with

with  ,

it follows that

,

it follows that

|

(14) |

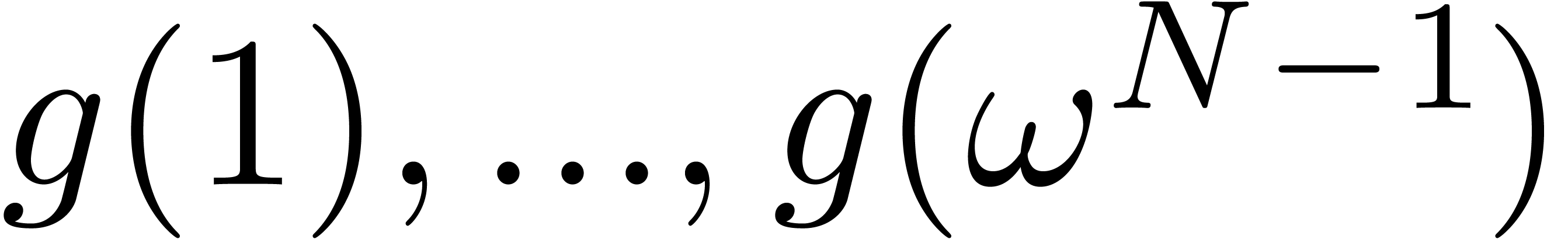

Let  be the time needed to compute

be the time needed to compute  -approximations of

-approximations of  . Given

. Given  ,

let

,

let  be the time needed to

be the time needed to  -evaluate

-evaluate  at

at  for

for  .

.

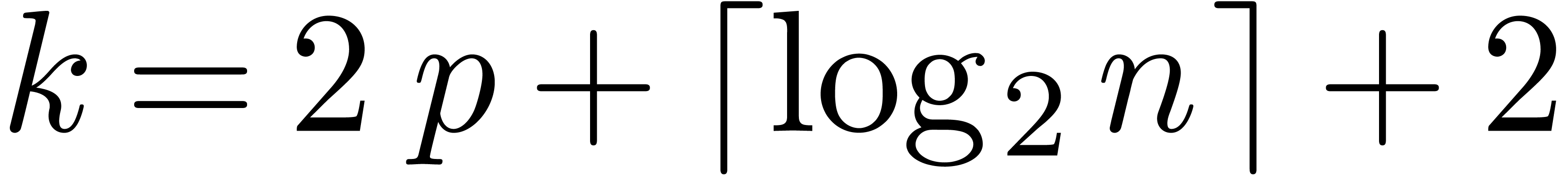

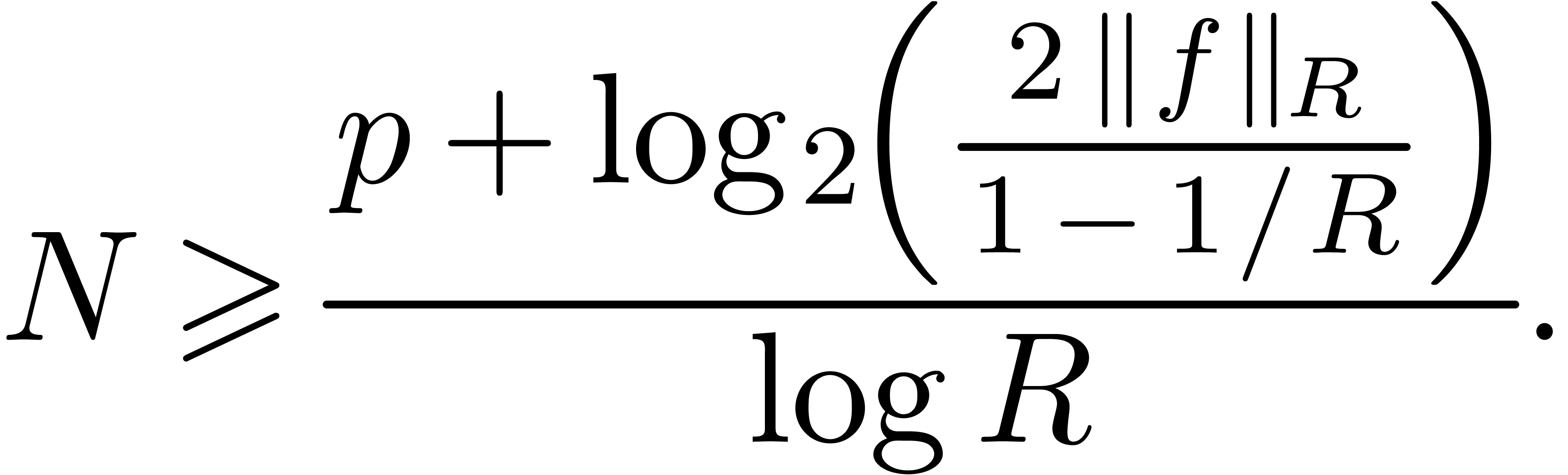

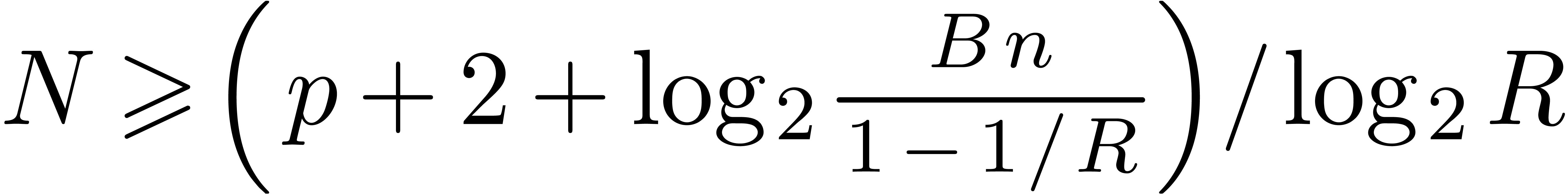

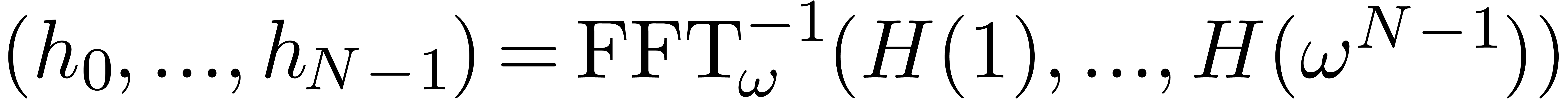

Proof. We first consider the case when  . Let

. Let  be

the smallest power of two with

be

the smallest power of two with

|

(15) |

For all  , the bound (14)

implies

, the bound (14)

implies

|

(16) |

The computation of  -approximations

of

-approximations

of  takes a time

takes a time  .

The

.

The  -evaluation of

-evaluation of  at

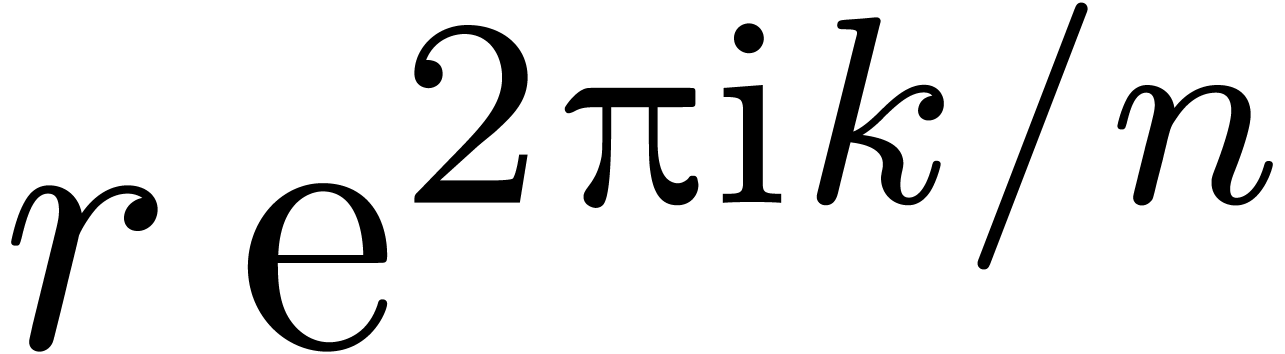

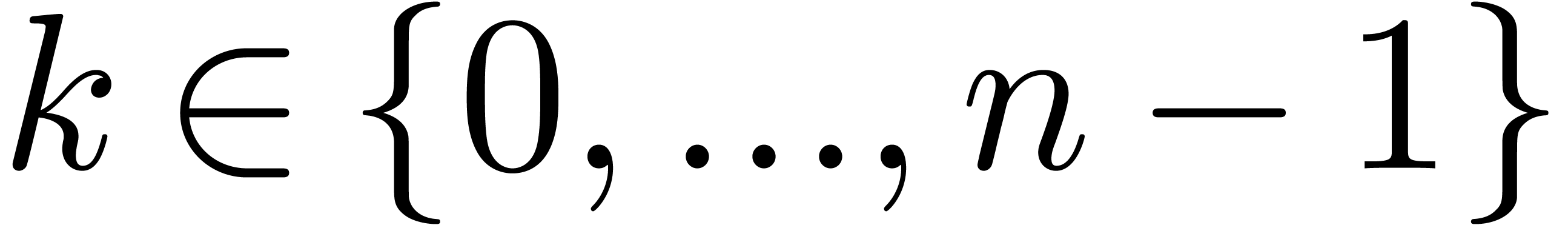

at  primitive roots of unity can be

done using

primitive roots of unity can be

done using  fast Fourier transforms of size

fast Fourier transforms of size  . This requires a time

. This requires a time  . If

. If  ,

we thus obtain the bound

,

we thus obtain the bound

The general case is reduced to the case  via a

change of variables

via a

change of variables  . This

requires computations to be carried out with an additional precision of

. This

requires computations to be carried out with an additional precision of

bits, leading to the complexity bound in

(a).

bits, leading to the complexity bound in

(a).

As to (b), we again start with the case when  . Taking

. Taking  to be the

smallest power of two with (15), we again obtain (16)

for all

to be the

smallest power of two with (15), we again obtain (16)

for all  . If

. If  , then we also notice that

, then we also notice that  for all

for all  . We may

. We may  -evaluate

-evaluate  at the

primitive

at the

primitive  -th roots of unity

in time

-th roots of unity

in time  . We next retrieve

the coefficients of the polynomial

. We next retrieve

the coefficients of the polynomial up to

precision

up to

precision  using one inverse fast Fourier

transform of size

using one inverse fast Fourier

transform of size  . In the

case when

. In the

case when  , we thus obtain

, we thus obtain

In general, replacing  by

by  yields the bound in (b).

yields the bound in (b).

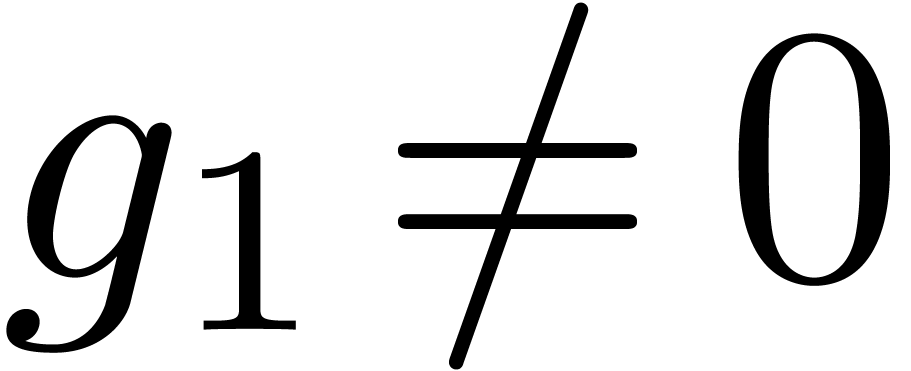

Let us now consider two convergent power series  with

with  ,

,  and

and  . Then

. Then  is well-defined and

is well-defined and  . In

fact, the series

. In

fact, the series  ,

,  and

and  still converge on a compact

disc of radius

still converge on a compact

disc of radius  . Let

. Let  be such that

be such that  ,

,

and

and  .

Then (14) becomes

.

Then (14) becomes

|

(17) |

and similarly for  and

and  . In view of lemma 17, it is natural to

use an evaluation-interpolation scheme for the computation of

. In view of lemma 17, it is natural to

use an evaluation-interpolation scheme for the computation of  -approximations of

-approximations of  .

.

For a sufficiently large  and

and  , we evaluate

, we evaluate  on the

on the

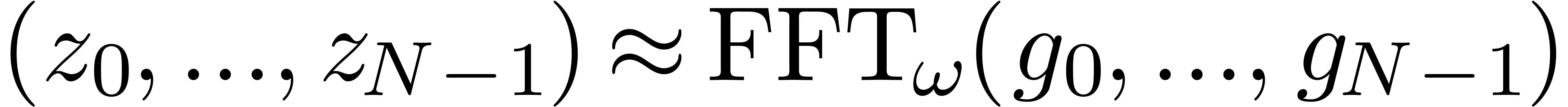

-th roots of unity

-th roots of unity  using one direct FFT on

using one direct FFT on  .

Using the fact that

.

Using the fact that  for all

for all  and the algorithm for multi-point evaluation from the previous section,

we next compute

and the algorithm for multi-point evaluation from the previous section,

we next compute  . Using one

inverse FFT, we finally recover the coefficients of the polynomial

. Using one

inverse FFT, we finally recover the coefficients of the polynomial  with

with  for all

for all  . Using the tail bound (17) for

. Using the tail bound (17) for

,

,  ,

,  and a sufficiently large

and a sufficiently large

, the differences

, the differences  can be made as small as needed. More precisely, the

algorithm goes as follows:

can be made as small as needed. More precisely, the

algorithm goes as follows:

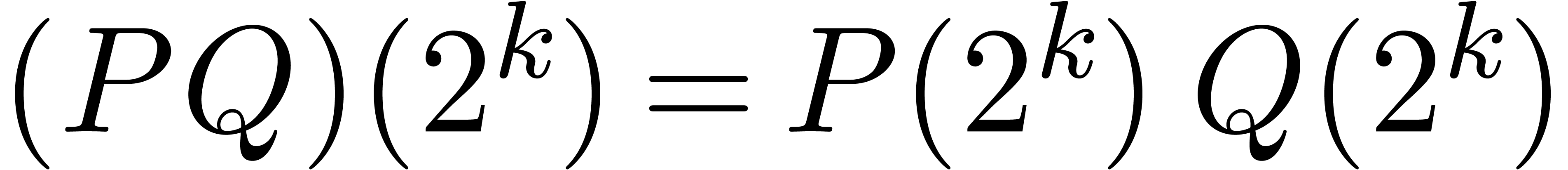

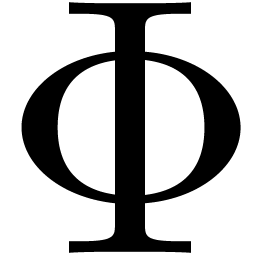

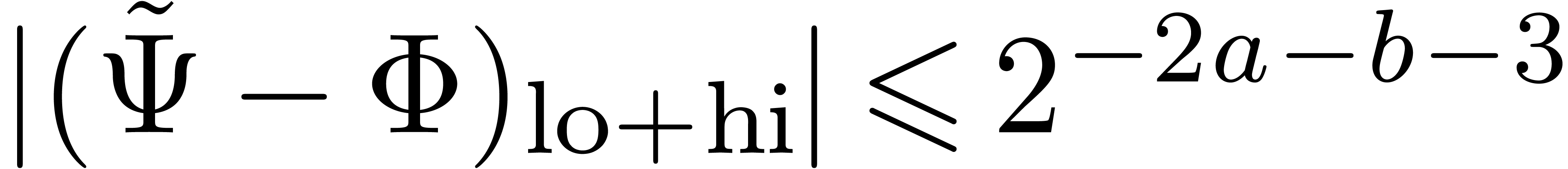

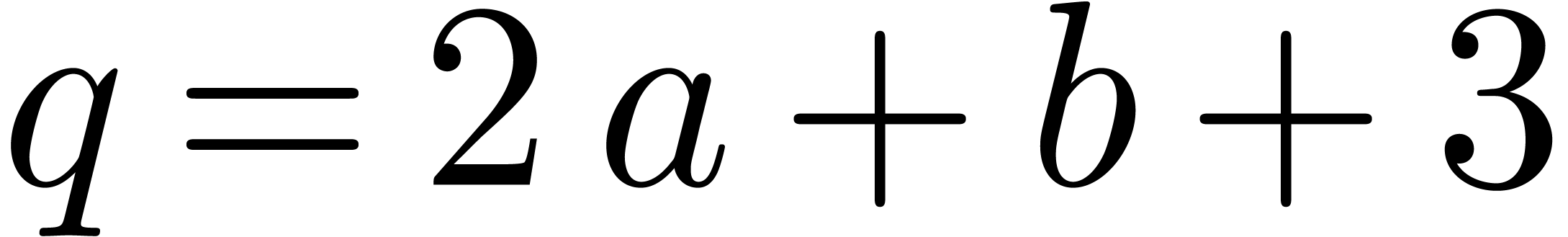

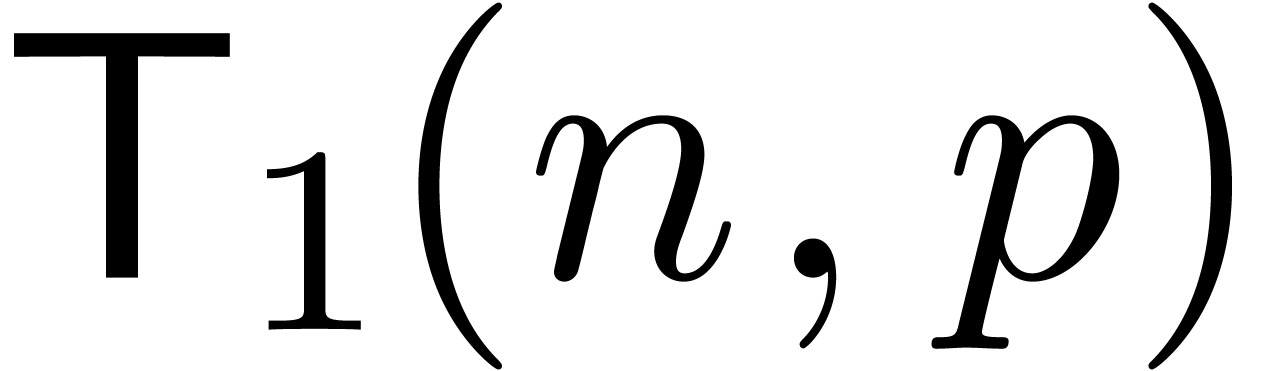

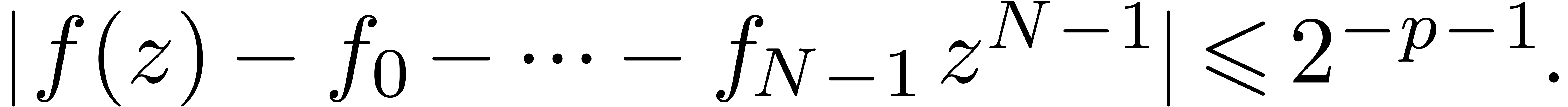

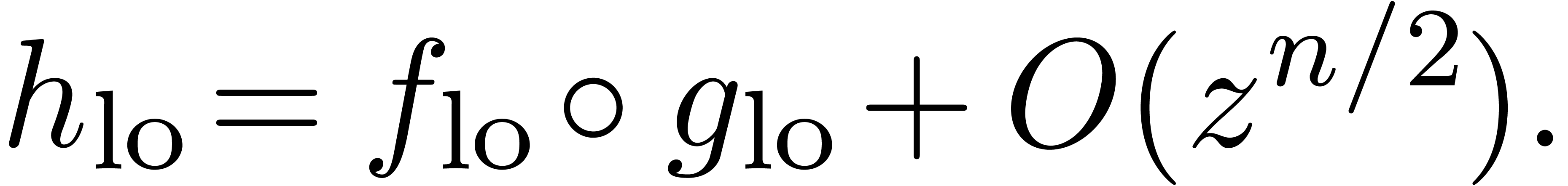

Algorithm compose

with

with  and

and  ,

,

such that we have bounds  ,

,

and

and

,

,  and

and  for certain

for certain

-approximations

for

-approximations

for

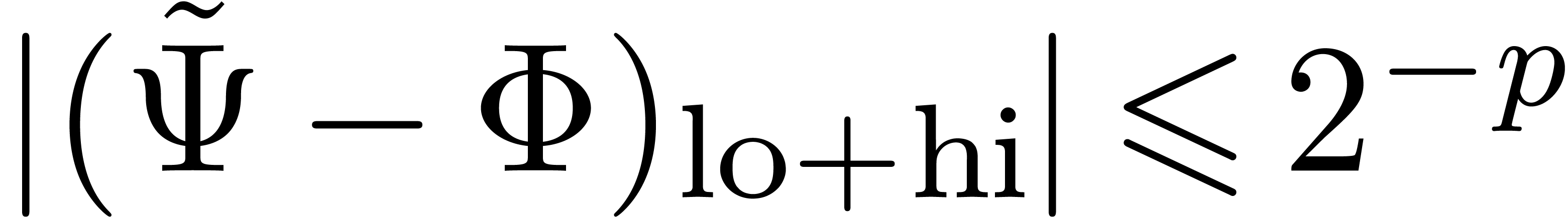

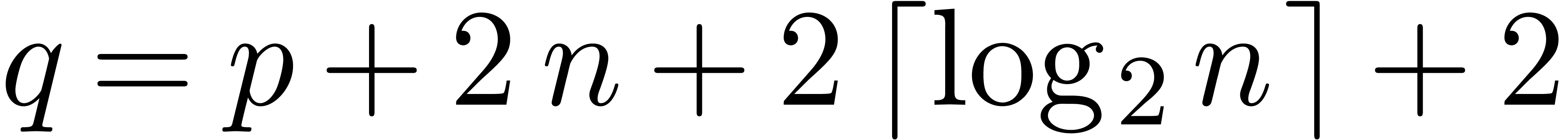

Step 1. [Determine auxiliary degree and precision]

Let  be smallest with

be smallest with  and

and

Let  , so that

, so that

Step 2. [Evaluate  on roots of

unity

on roots of

unity  ]

]

Let

Compute a  -approximation

-approximation

with

with

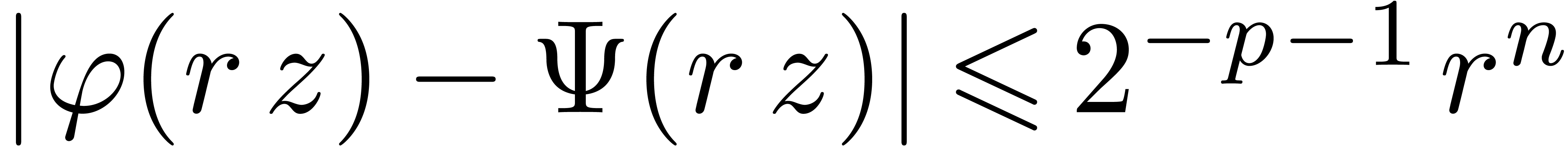

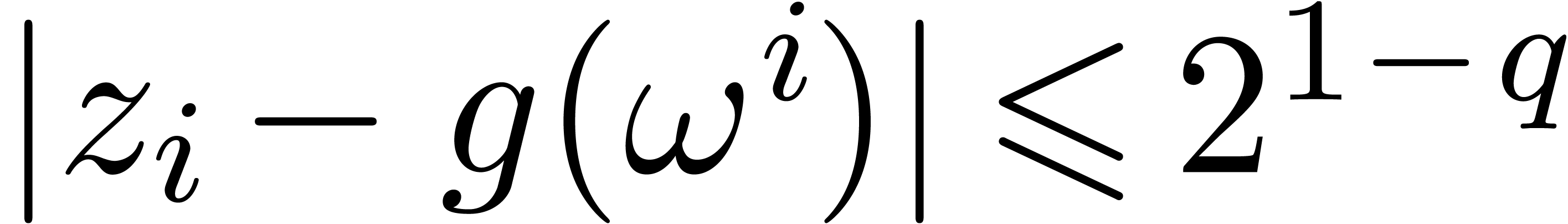

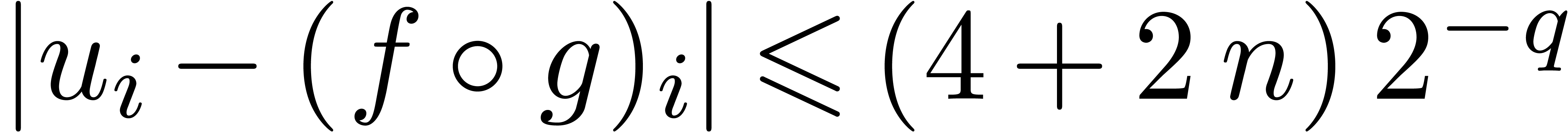

We will show that  for all

for all

Step 3. [Evaluate  on

on  ]

]

Let

Compute a  -approximation

-approximation

We will show that  for all

for all

Step 4. [Interpolate]

Compute a  -approximation

-approximation

We will show that  for all

for all

Return

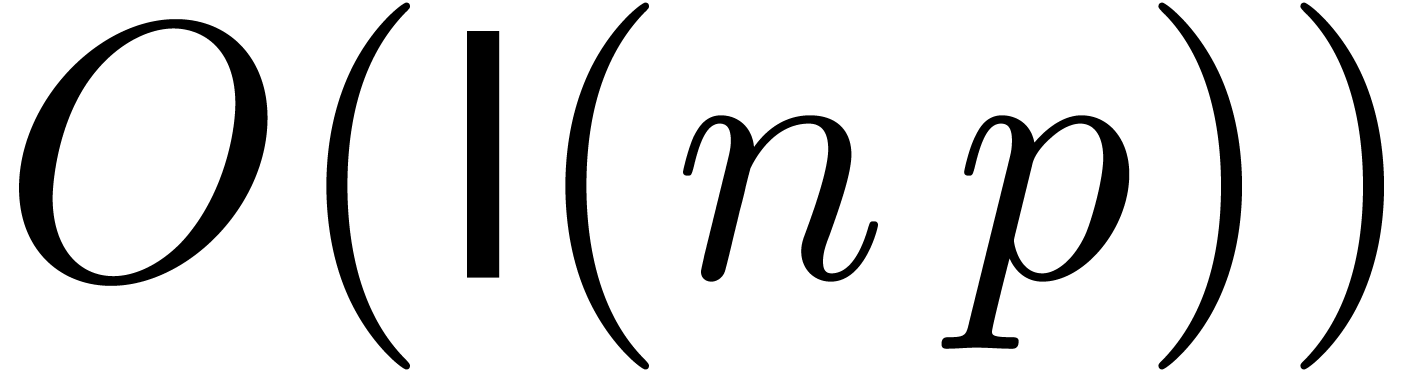

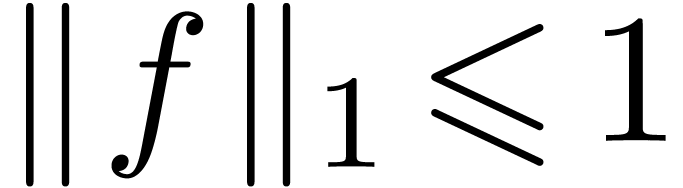

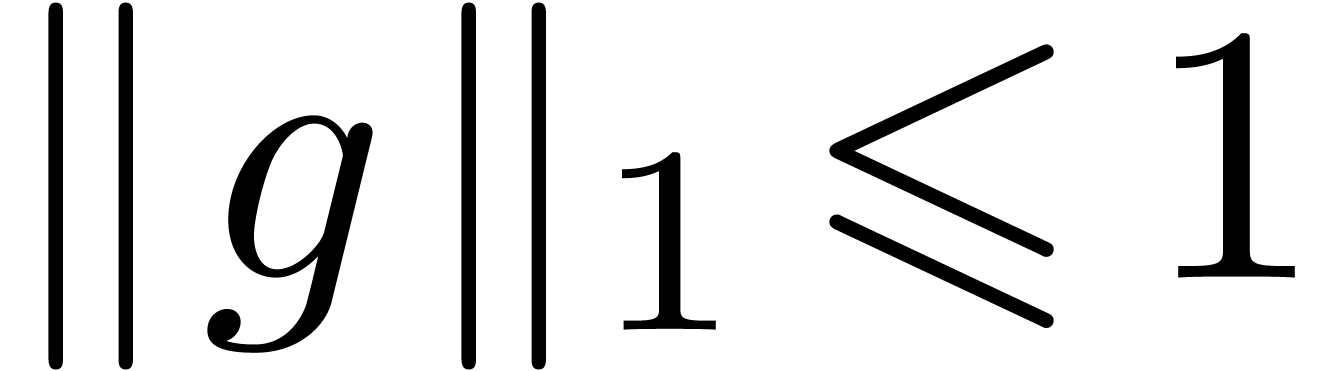

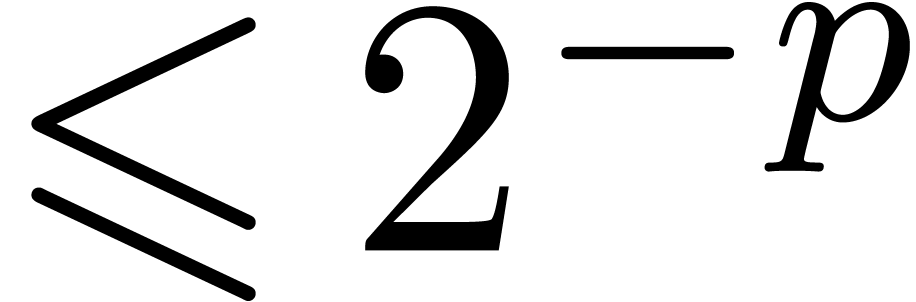

be power series with

be power series with  and

and  . Assume

that

. Assume

that  and

and  .

Given

.

Given  , we may compute

, we may compute

-approximations for

-approximations for  (as a function of

(as a function of  and

and  ) in time

) in time  .

.

Proof. Let us first prove the correctness of the

algorithm. The choice of  and the tail bound (17) for

and the tail bound (17) for  imply

imply  . This ensures that we indeed have

. This ensures that we indeed have  for all

for all  at the end of step 2. For

at the end of step 2. For  , we also have

, we also have

This proves the bound stated at the end of step 3. As to the last bound,

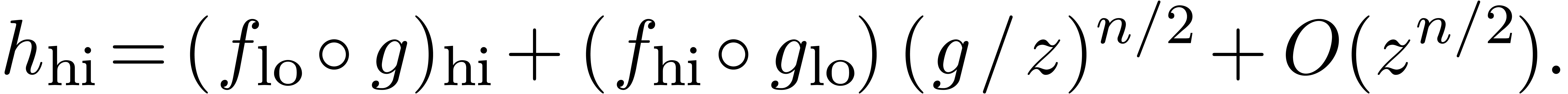

let  . Then

. Then  and

and  . Using the fact that

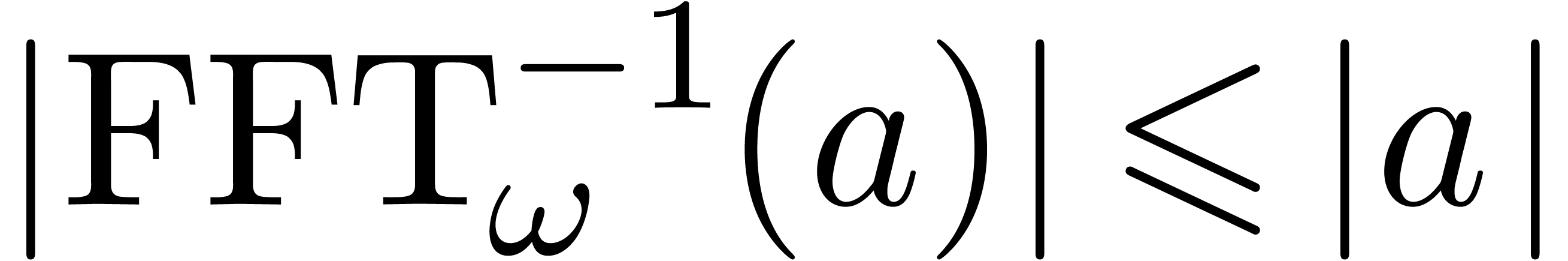

. Using the fact that

for all vectors

for all vectors  of

length

of

length  , we obtain

, we obtain

This proves the second bound. Our choice of  implies the correctness of the algorithm.

implies the correctness of the algorithm.

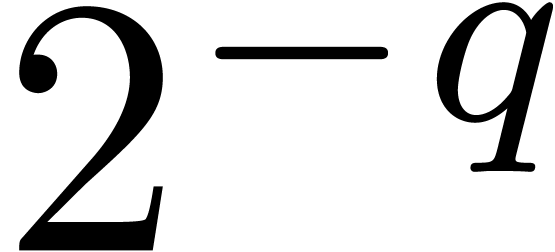

As to the complexity bound, the FFT transform in step 2 can be done in time

By lemma 11, the multi-point evaluation in step 3 can be performed in time

The inverse FFT transform in step 4 can be performed within the same time as a direct FFT transform. This leads to the overall complexity bound

since  .

.

be convergent power series with

be convergent power series with

and

and  .

Given

.

Given  , we may compute

, we may compute

-approximations for

-approximations for  (as a function of

(as a function of  and

and  ) in time

) in time

.

.

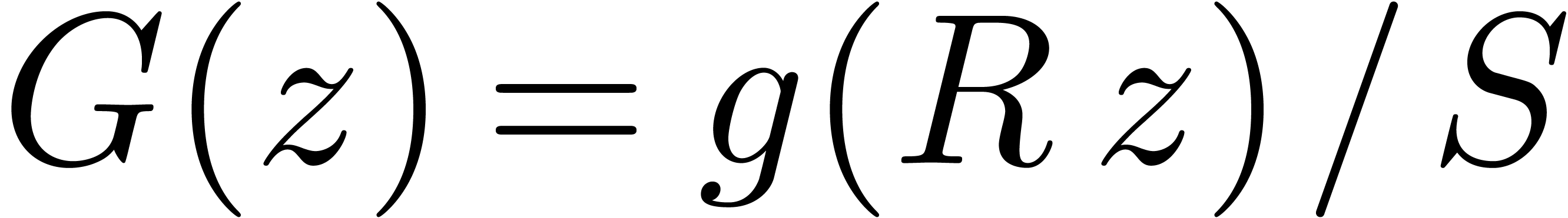

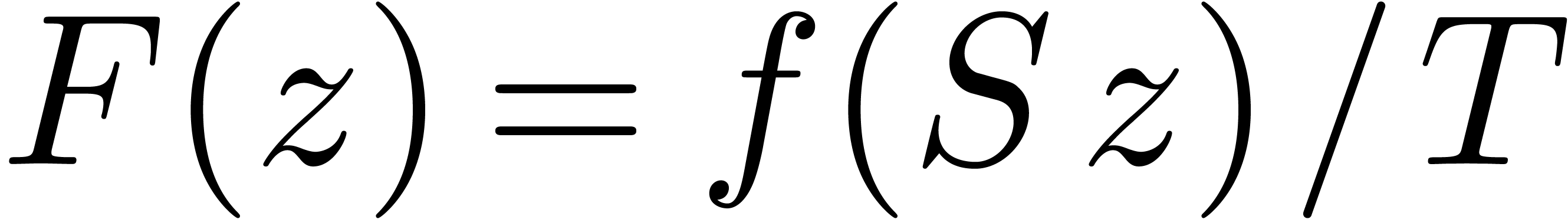

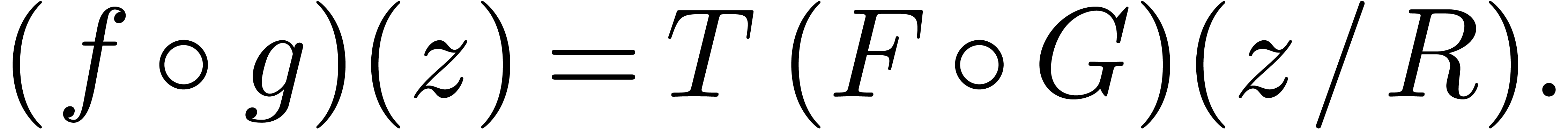

Proof. Let  be

sufficiently small such that

be

sufficiently small such that  and

and  . Consider the series

. Consider the series  and

and  , so that

, so that

Let  . By the theorem, we may

compute

. By the theorem, we may

compute  -approximations

-approximations  of

of  in time

in time  . Using

. Using  additional

additional

-bit multiplications, we may

compute

-bit multiplications, we may

compute

with  for all

for all  .

This can again be done in time

.

This can again be done in time  .

.

be convergent power series with

be convergent power series with

, such that

, such that  is an ordinary generating function. Then we may compute

is an ordinary generating function. Then we may compute

(as a function of

(as a function of  and

and

) in time

) in time  .

.

Proof. It suffices to take  in corollary 19 and round the results.

in corollary 19 and round the results.

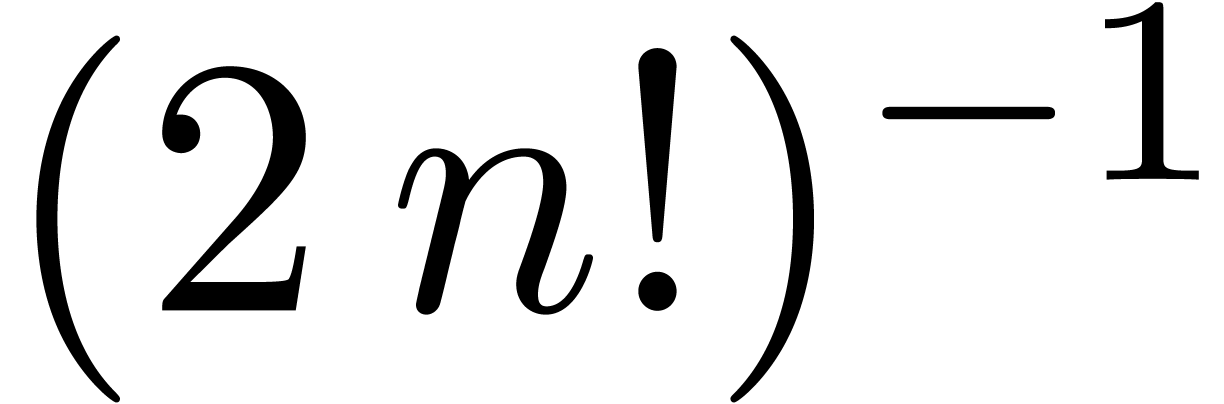

be convergent power series with

be convergent power series with

such that

such that  is an

exponential generating function. Then we may compute

is an

exponential generating function. Then we may compute  (as a function of

(as a function of  and

and  ) in time

) in time  .

.

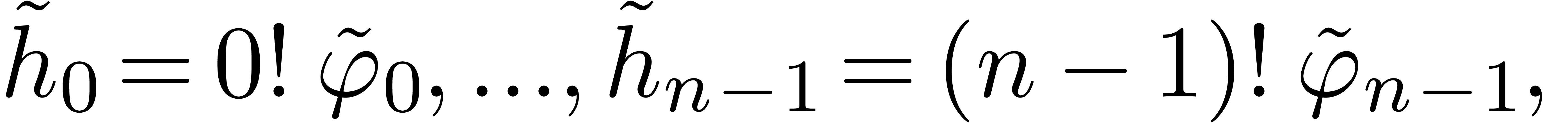

Proof. Applying corollary 19 for

, we obtain

, we obtain  -approximations

-approximations  of

of  in time

in time  .

Using

.

Using  additional

additional  -bit

multiplications of total cost

-bit

multiplications of total cost  ,

we may compute

,

we may compute

with  for all

for all  .

The

.

The  are obtained by rounding the

are obtained by rounding the  to the nearest integers.

to the nearest integers.

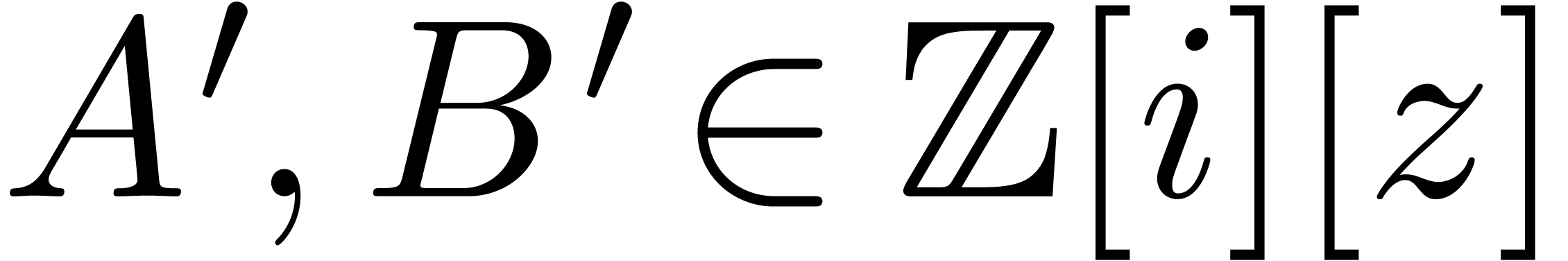

be power series with

be power series with  and

and  . Let

. Let

and

and  be positive

increasing functions with

be positive

increasing functions with  and

and  . Given

. Given  ,

we may compute

,

we may compute  -approximations

for

-approximations

for  (as a function of

(as a function of  and

and  ) in time

) in time  .

.

Proof. Without loss of generality, we may assume

that  for

for  .

In the proof of corollary 19, we may therefore choose

.

In the proof of corollary 19, we may therefore choose  , which yields

, which yields  and

and  . It follows that

. It follows that  and we conclude in a similar way as in the proof of

corollary 19.

and we conclude in a similar way as in the proof of

corollary 19.

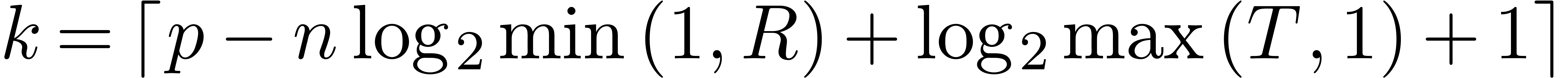

Let  be such that

be such that  and

and

. Given an order

. Given an order  , we have shown in the previous section how to

compute

, we have shown in the previous section how to

compute  efficiently, as a function of

efficiently, as a function of  and

and  . Since

. Since

only depends on

only depends on  and

and

, we may consider the

relaxed composition problem in which

, we may consider the

relaxed composition problem in which  and

and  are given progressively, and where we

require each coefficient

are given progressively, and where we

require each coefficient  to be output as soon as

to be output as soon as

and

and  are known.

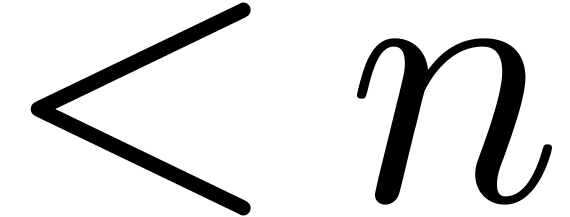

Similarly, in the semi-relaxed composition problem, the

coefficients

are known.

Similarly, in the semi-relaxed composition problem, the

coefficients  are known beforehand, but

are known beforehand, but  are given progressively. In that case, we require

are given progressively. In that case, we require  to be output as soon as

to be output as soon as  are

known. The relaxed and semi-relaxed settings are particularly useful for

the resolution of implicit equations involving functional composition.

We refer to [vdH02, vdH07] for more details

about relaxed computations with power series.

are

known. The relaxed and semi-relaxed settings are particularly useful for

the resolution of implicit equations involving functional composition.

We refer to [vdH02, vdH07] for more details

about relaxed computations with power series.

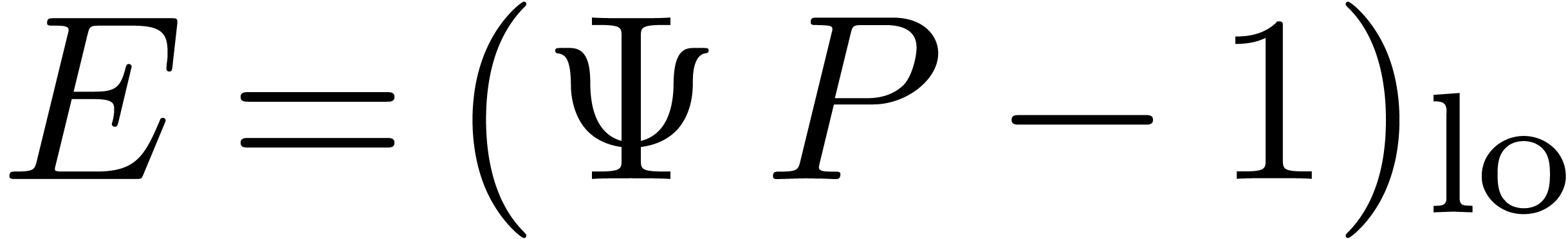

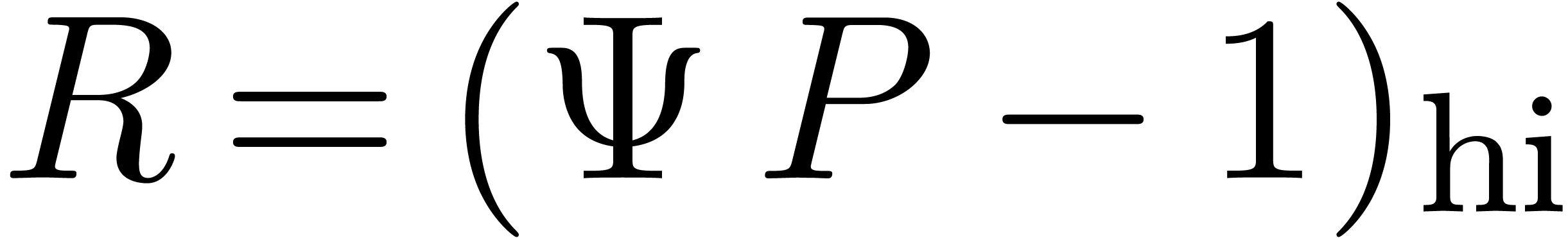

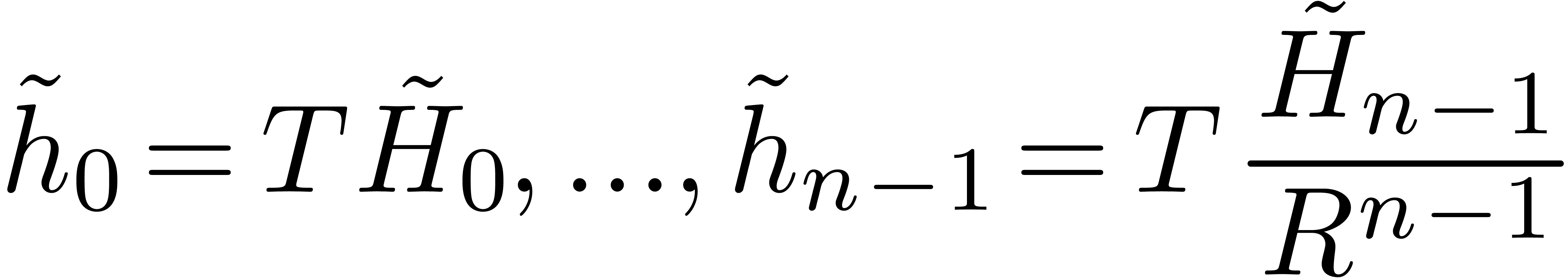

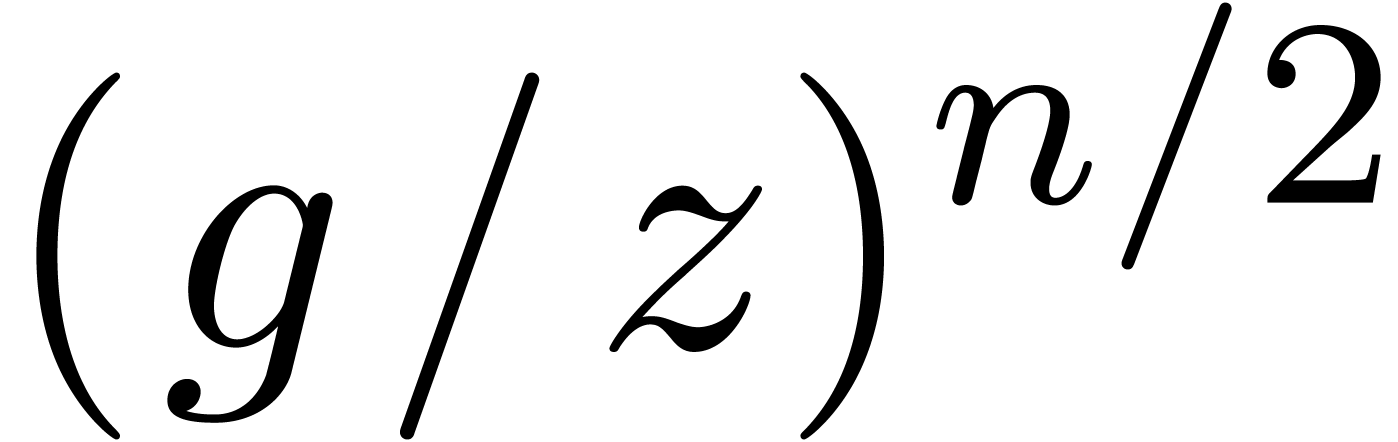

Let  . In this section, we

consider the problem of computing the semi-relaxed composition

. In this section, we

consider the problem of computing the semi-relaxed composition  up to order

up to order  .

If

.

If  , then we simply have

, then we simply have

. For

. For  , we denote

, we denote

and similarly for  and

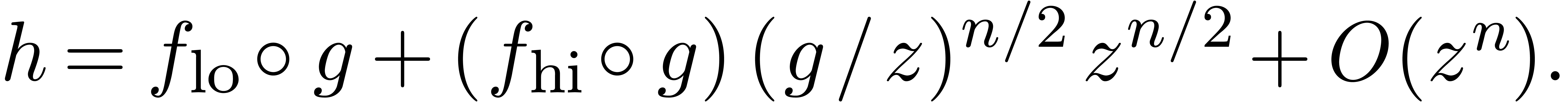

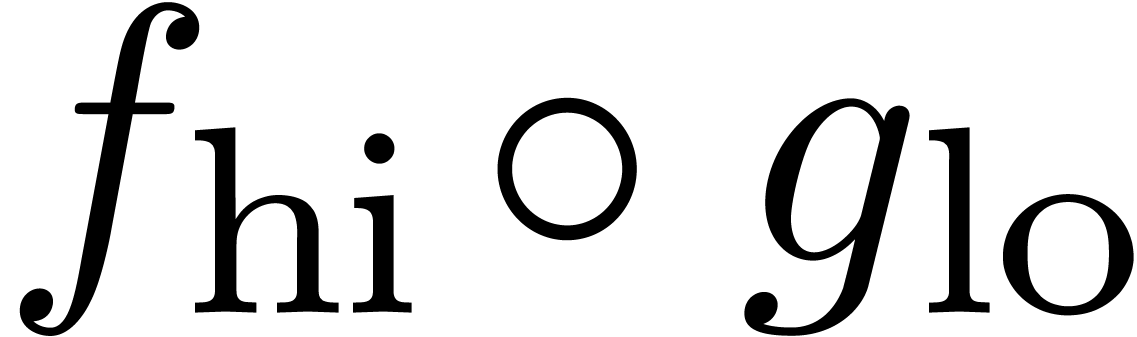

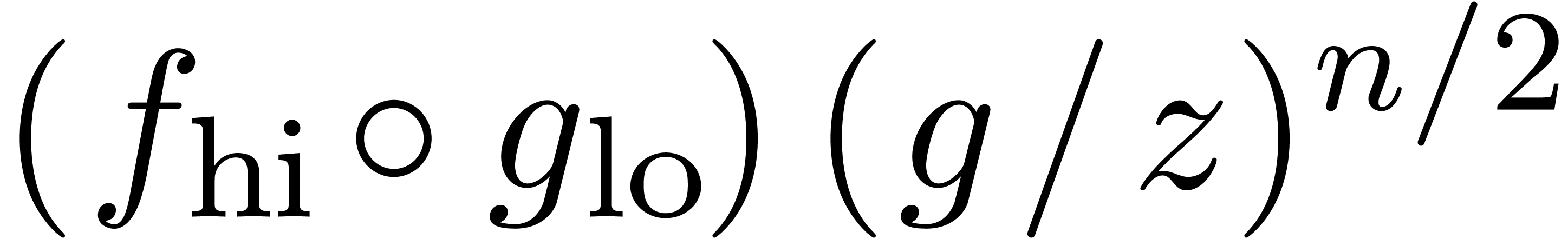

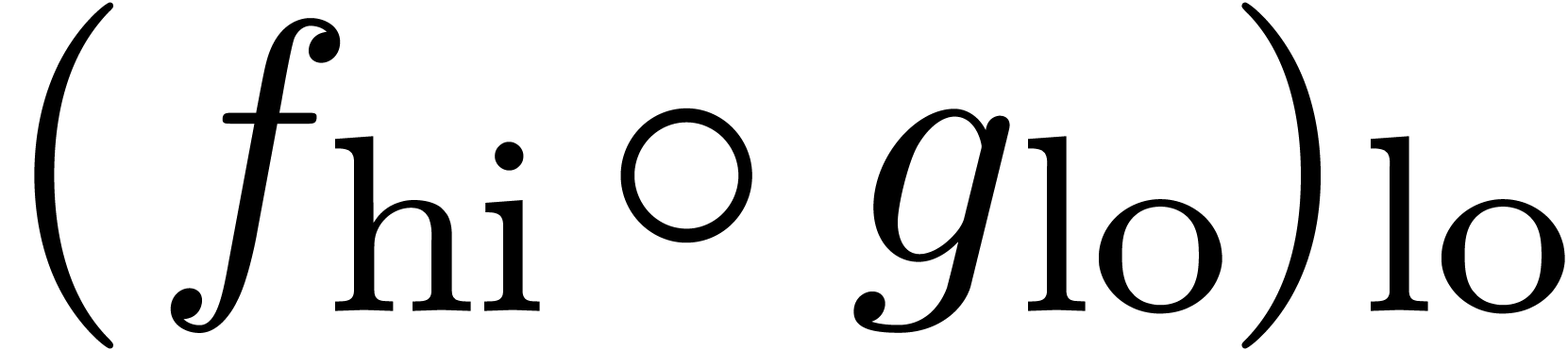

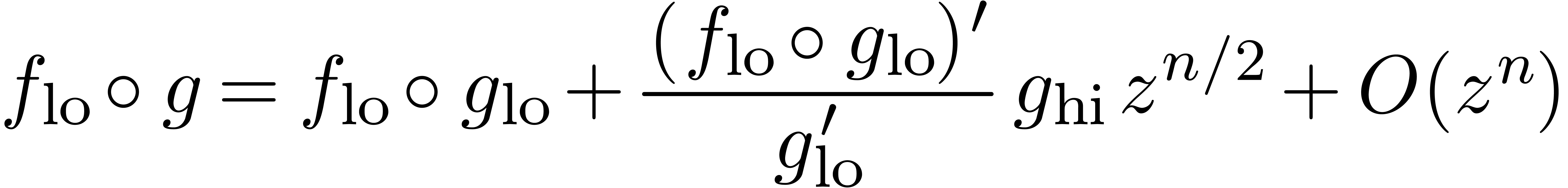

and  . Our algorithm relies on the identity

. Our algorithm relies on the identity

|

(18) |

The first part  of

of  is

computed recursively, using one semi-relaxed composition at order

is

computed recursively, using one semi-relaxed composition at order  :

:

As soon as  is completely known, we compute

is completely known, we compute  at order

at order  ,

using one of the algorithms for composition from the previous section.

We also compute

,

using one of the algorithms for composition from the previous section.

We also compute  at order

at order  using binary powering. We are now allowed to recursively compute the

second part

using binary powering. We are now allowed to recursively compute the

second part  of

of  ,

using

,

using

This involves one semi-relaxed composition  at

order

at

order  and one semi-relaxed multiplication

and one semi-relaxed multiplication  at order

at order  .

.

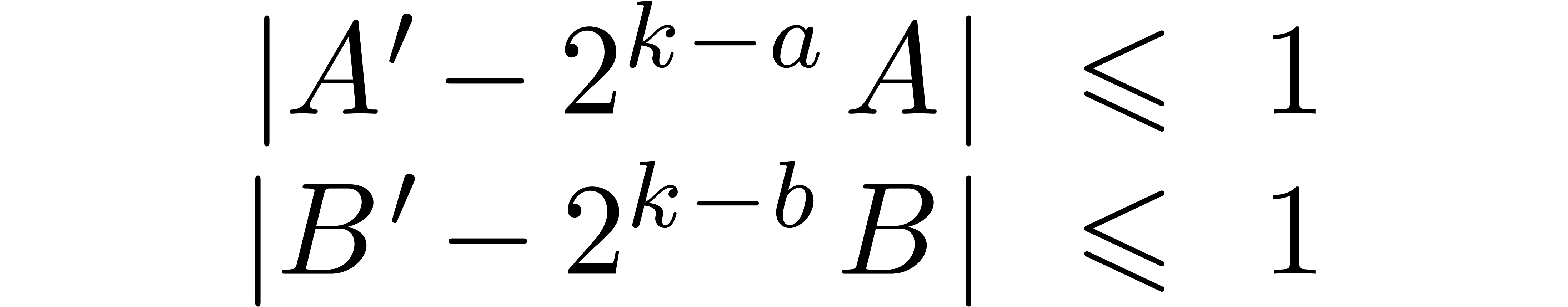

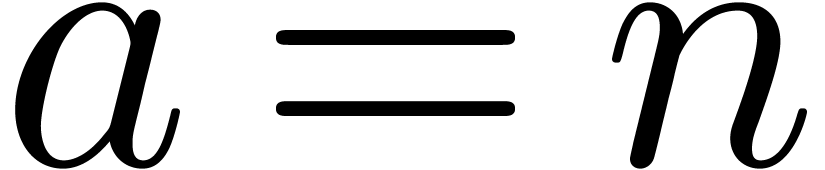

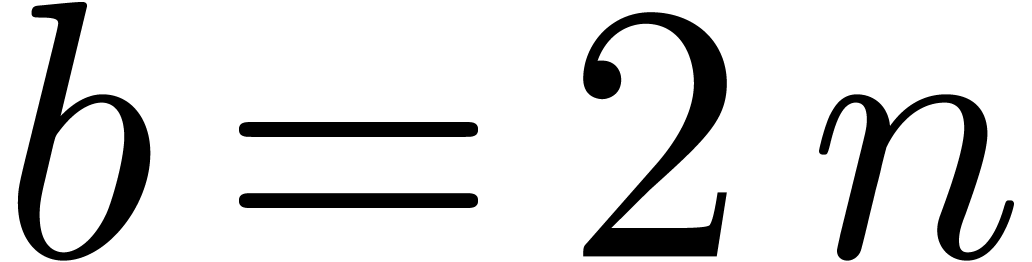

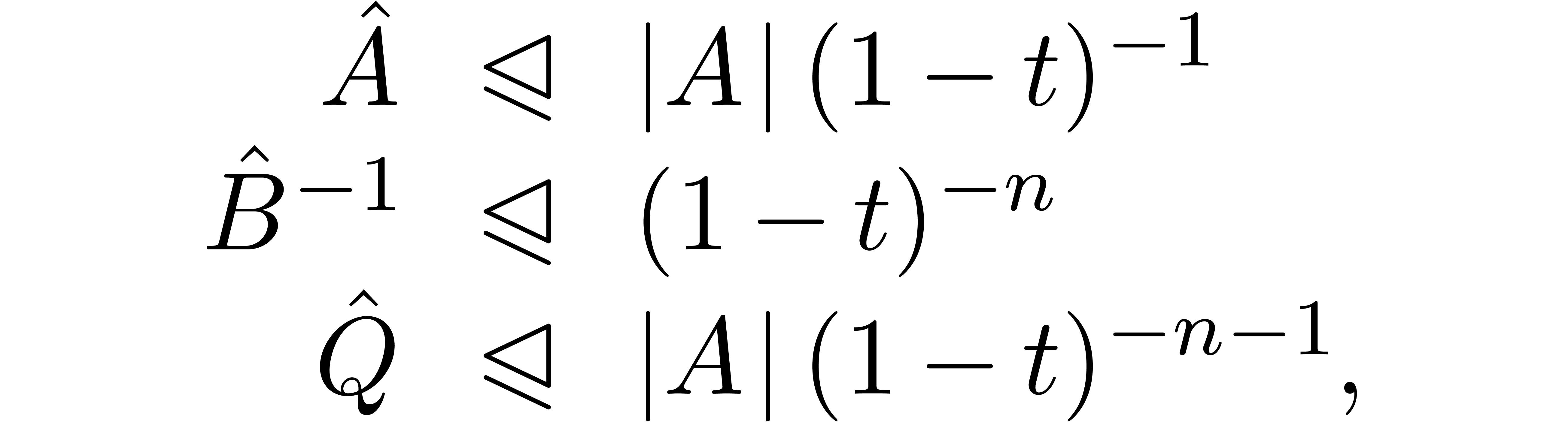

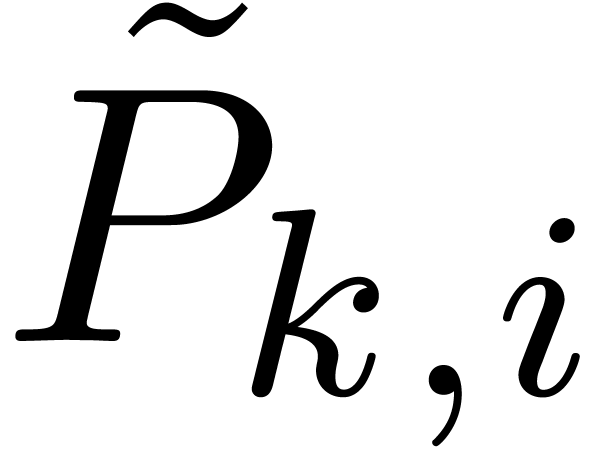

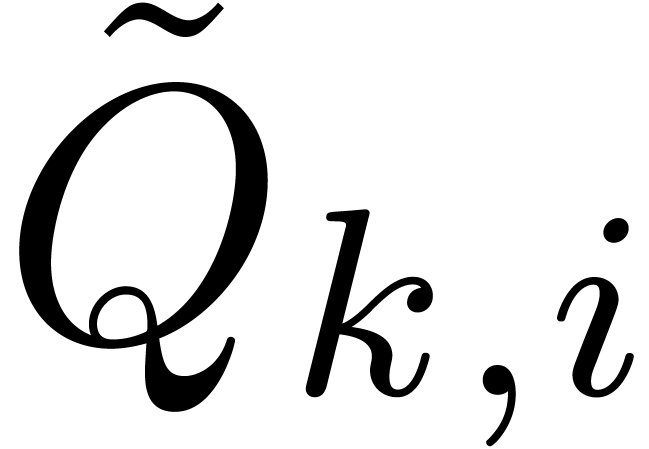

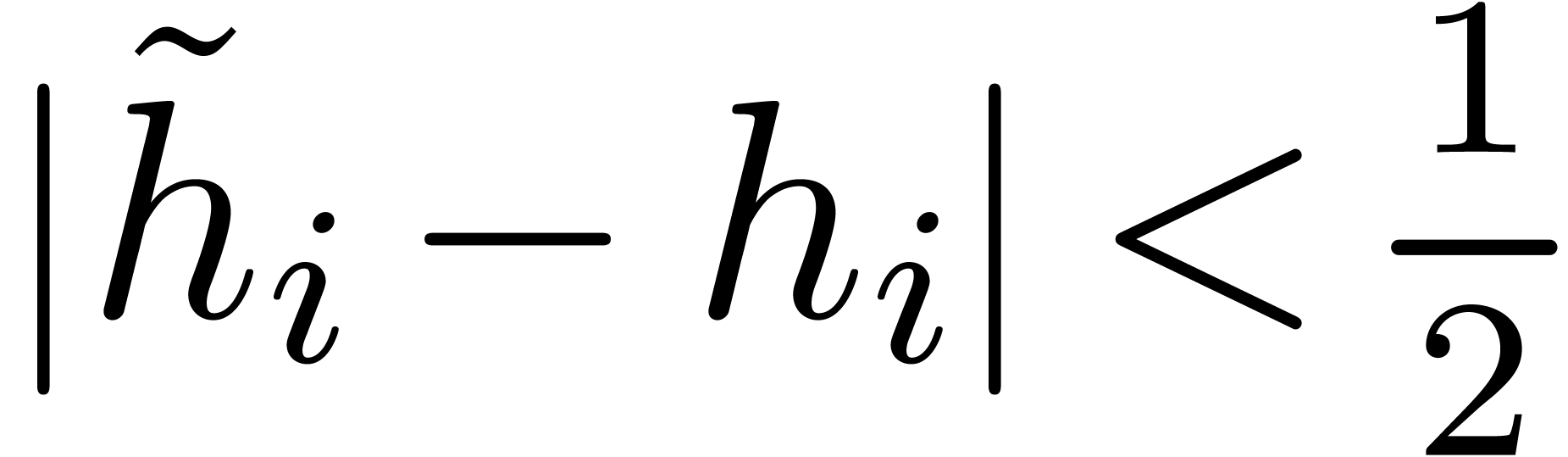

Assume now that  for all

for all  and

and  . Consider the problem of

computing

. Consider the problem of

computing  -approximations of

-approximations of

. In our algorithm, it will

suffice to conduct the various computations with the following

precisions:

. In our algorithm, it will

suffice to conduct the various computations with the following

precisions:

We recursively compute  -approximations

of

-approximations

of  .

.

We compute  -approximations

of

-approximations

of  .

.

We recursively compute  -approximations

of

-approximations

of  .

.

We compute  -approximations

of the coefficients of

-approximations

of the coefficients of  .

.

We compute  -approximations

of the coefficients of

-approximations

of the coefficients of  .

.

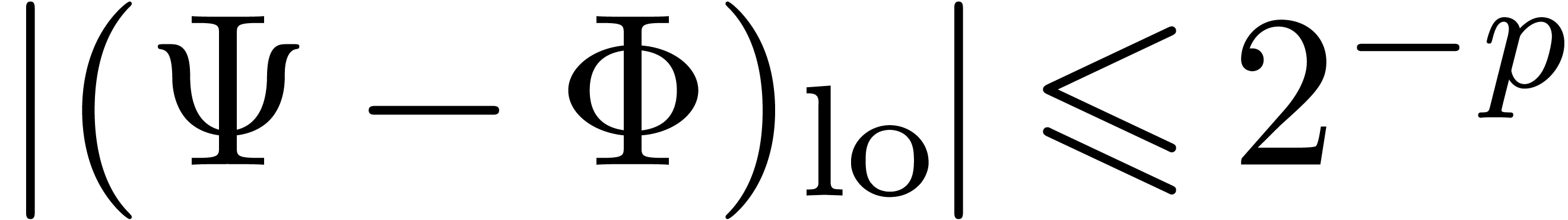

Let us show that this indeed enables us to obtain the desired  -approximations for

-approximations for  . This is clear for the coefficients of

. This is clear for the coefficients of  . As to the second half, we have

the bounds

. As to the second half, we have

the bounds

and

These bounds justify the extra number of bits needed in the computations

of  and

and  respectively.

respectively.

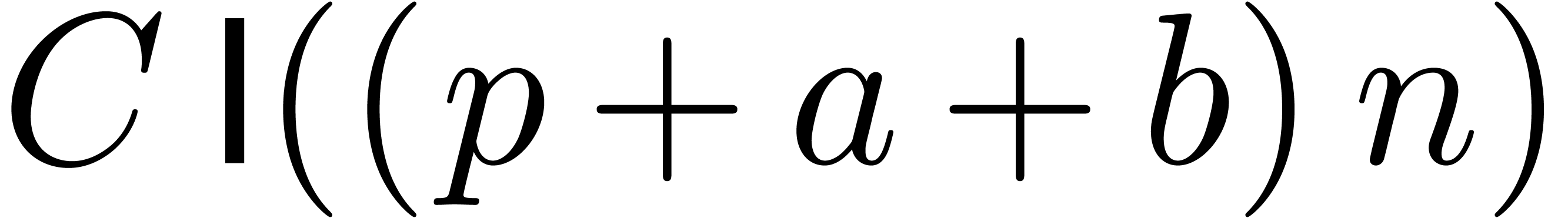

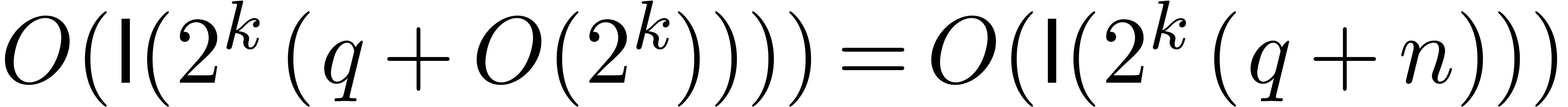

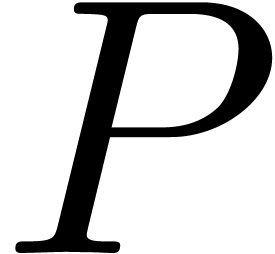

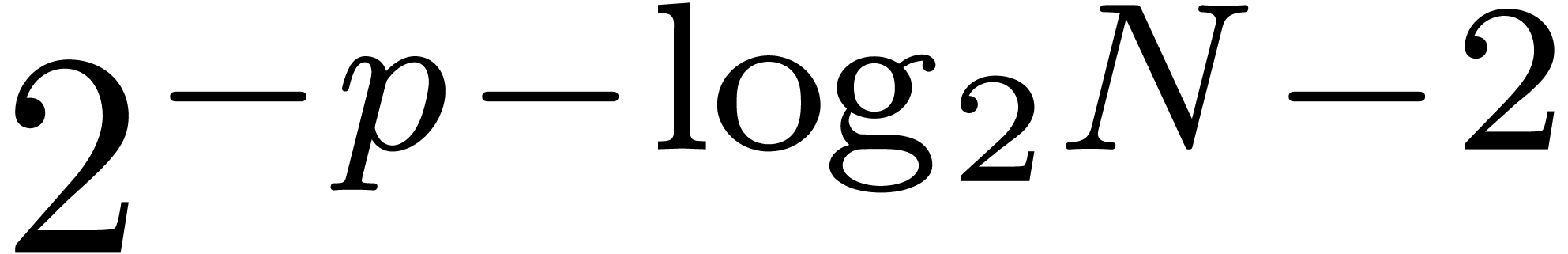

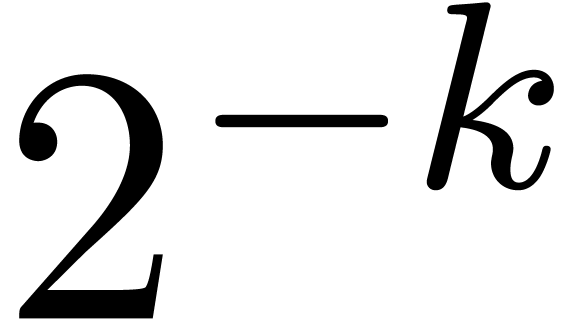

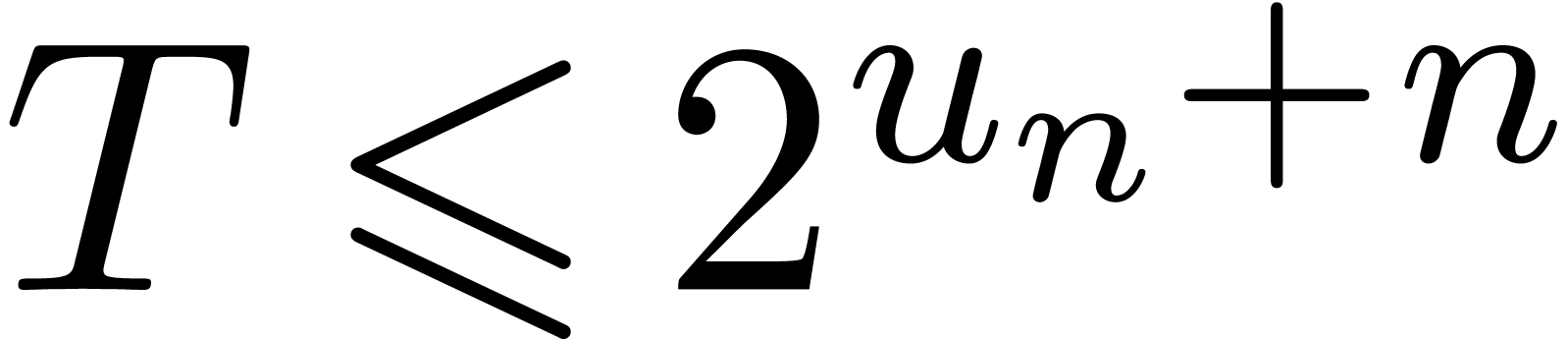

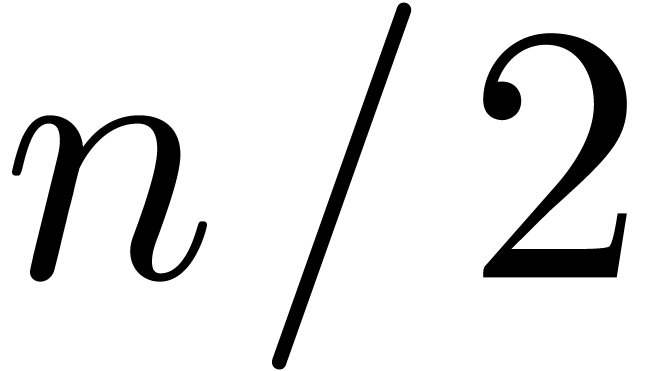

Let us finally analyze the complexity of the above algorithm. We will

denote by  the complexity of multiplying two

the complexity of multiplying two

-bit integer polynomials of

degrees

-bit integer polynomials of

degrees  . Using Kronecker

multiplication, we have

. Using Kronecker

multiplication, we have  . We

denote by

. We

denote by  the cost of a semi-relaxed

multiplication of two

the cost of a semi-relaxed

multiplication of two  -bit

integer polynomials of degrees

-bit

integer polynomials of degrees  .

Using the fast relaxed multiplication algorithm from [vdH02],

we have

.

Using the fast relaxed multiplication algorithm from [vdH02],

we have  . We will denote by

. We will denote by

and

and  the cost of

classical and semi-relaxed composition for

the cost of

classical and semi-relaxed composition for  ,

,

and

and  as described above.

By theorem 18, we have

as described above.

By theorem 18, we have  .

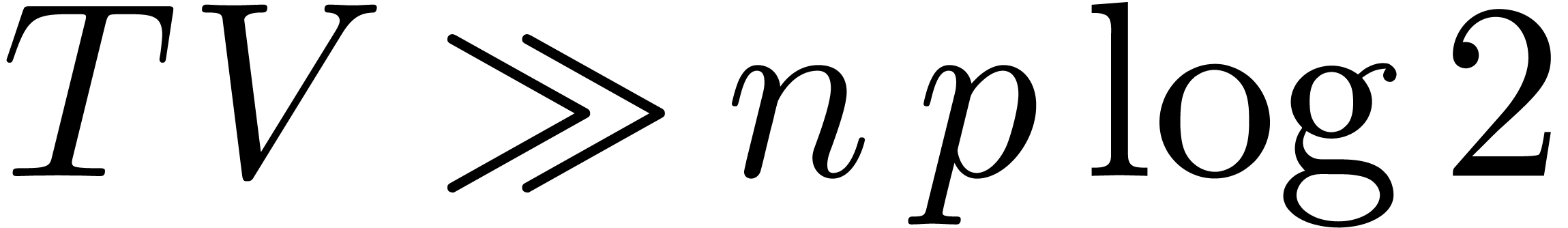

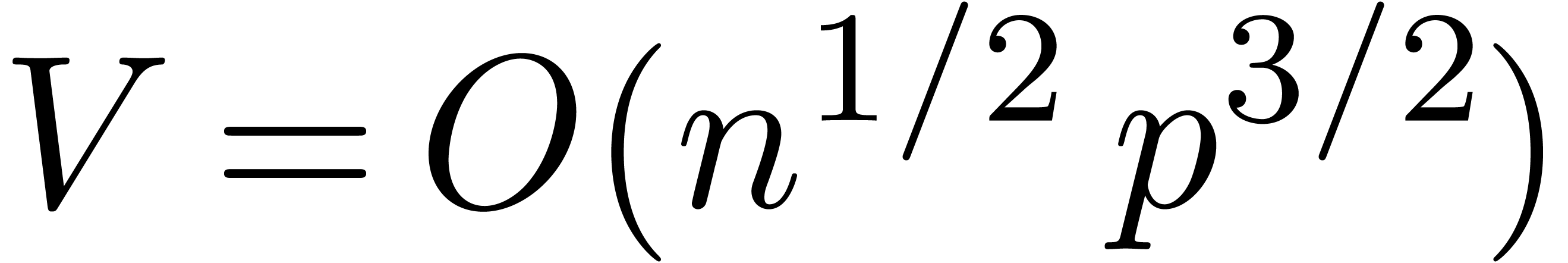

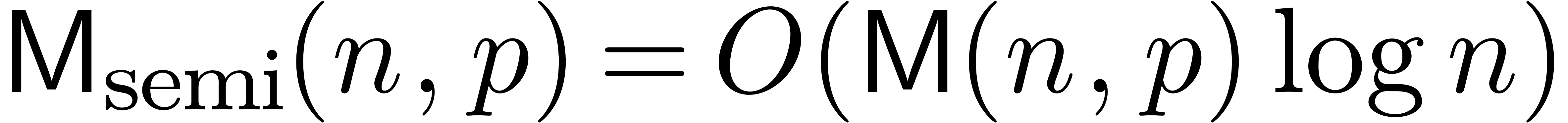

The complexity of the semi-relaxed composition satisfies the following

recursive bound:

.

The complexity of the semi-relaxed composition satisfies the following

recursive bound:

Using theorem 18, it follows by induction that

|

(19) |

From [BK75, vdH02], we also have

|

(20) |

Applying (19) for  and (20)

on

and (20)

on  , we obtain

, we obtain

We have proved the following theorem:

be power series with

be power series with  and

and  . Assume that

. Assume that  and

and  . The

computation of the semi-relaxed composition

. The

computation of the semi-relaxed composition  at

order

at

order  and up to an absolute error

and up to an absolute error  can be done in time

can be done in time  .

.

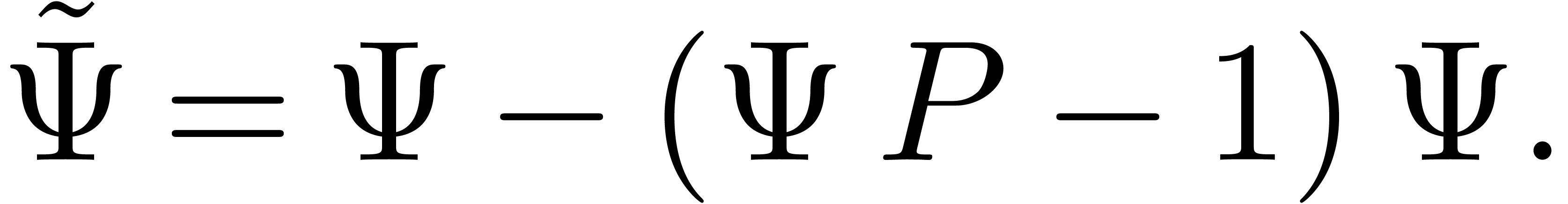

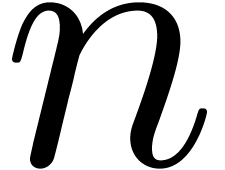

Let  be as in the previous section and

be as in the previous section and  . Assume also that

. Assume also that  . In order to compute the relaxed composition

. In order to compute the relaxed composition

, we again use the formula

(18), in combination with

, we again use the formula

(18), in combination with

The first  coefficients of

coefficients of  are still computed recursively, by performing a relaxed composition

are still computed recursively, by performing a relaxed composition  at order

at order  .

As soon as

.

As soon as  and

and  are

completely known, we may compute the composition

are

completely known, we may compute the composition  at order

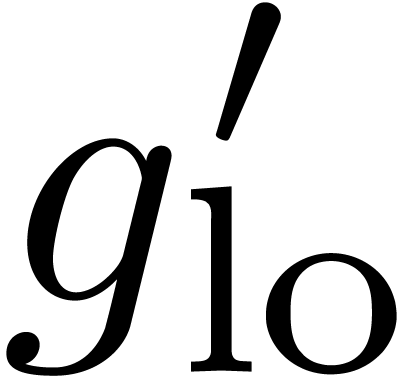

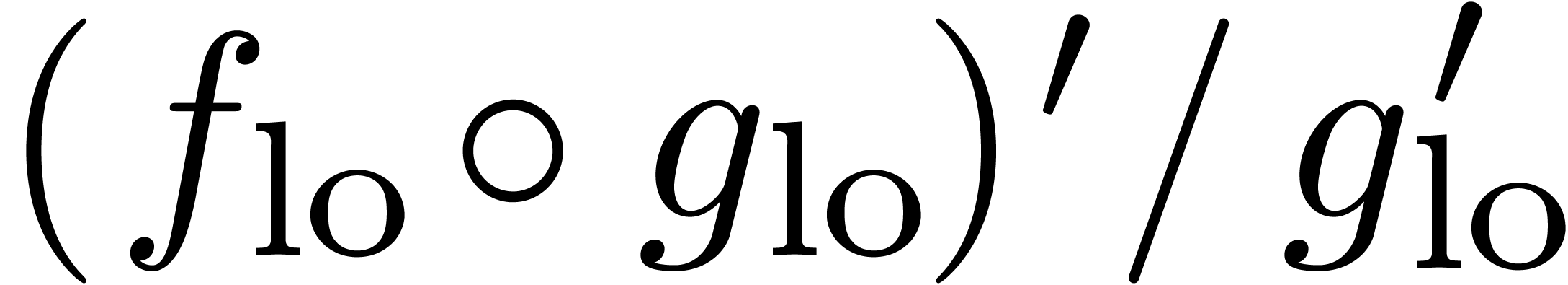

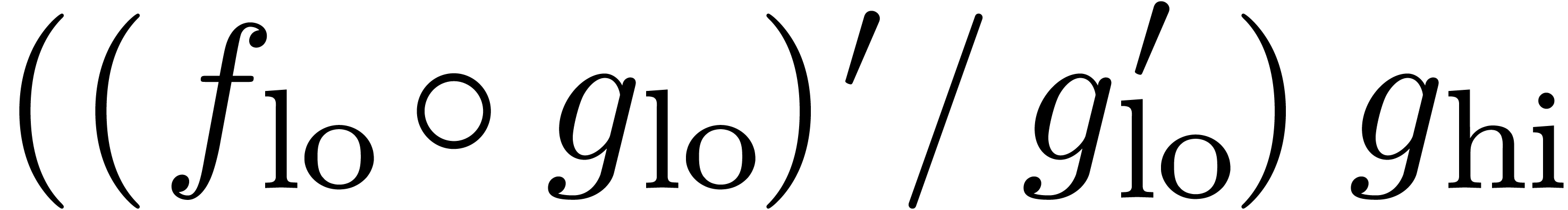

at order  using the algorithm from section 4. Differentiation and division by

using the algorithm from section 4. Differentiation and division by  also yields

also yields  at order

at order  . The product

. The product  can therefore

be computed using one semi-relaxed multiplication.

can therefore

be computed using one semi-relaxed multiplication.

Let  . This time, the

intermediate computations should be conducted with the following

precisions:

. This time, the

intermediate computations should be conducted with the following

precisions:

We recursively compute  -approximations

of the coefficients of

-approximations

of the coefficients of  .

.

We compute  -approximations

of the coefficients of

-approximations

of the coefficients of  .

.

We compute  -approximations

of the coefficients of

-approximations

of the coefficients of  .

.

We compute  -approximations

of the coefficients of

-approximations

of the coefficients of  .

.

Indeed, we have

Denoting by  the complexity of relaxed

composition, we obtain

the complexity of relaxed

composition, we obtain

It follows that

be power series with

be power series with  ,

,  and

and  . Assume that

. Assume that  and

and

. The computation of the

relaxed composition

. The computation of the

relaxed composition  at order

at order  and up to an absolute error

and up to an absolute error  can be done in

time

can be done in

time  .

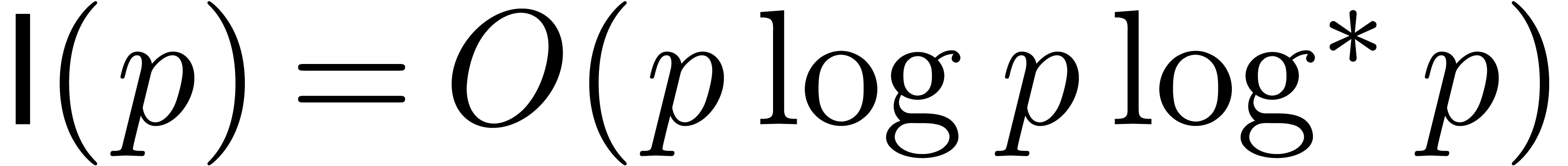

.

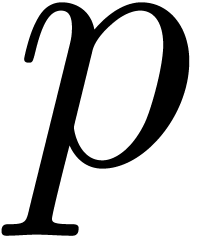

Remark

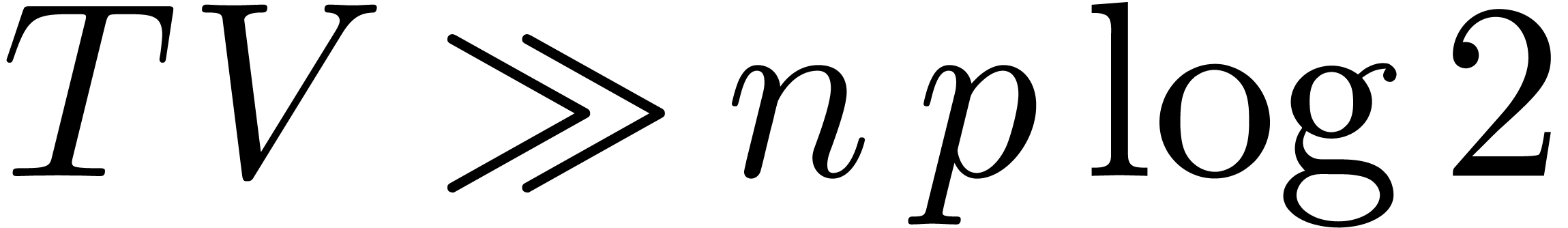

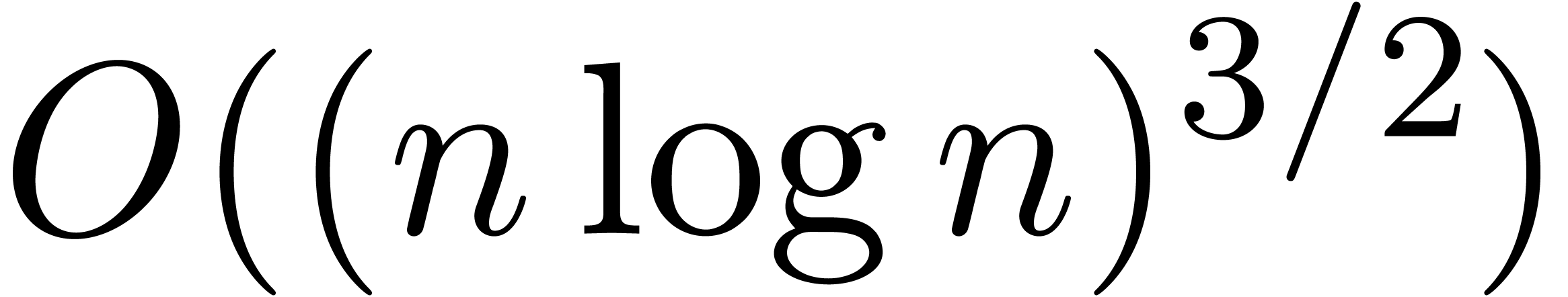

Theorem 24 improves on this bound in the frequent case when

. Unfortunately, we have not

yet been able to prove a quasi-linear bound

. Unfortunately, we have not

yet been able to prove a quasi-linear bound  .

.

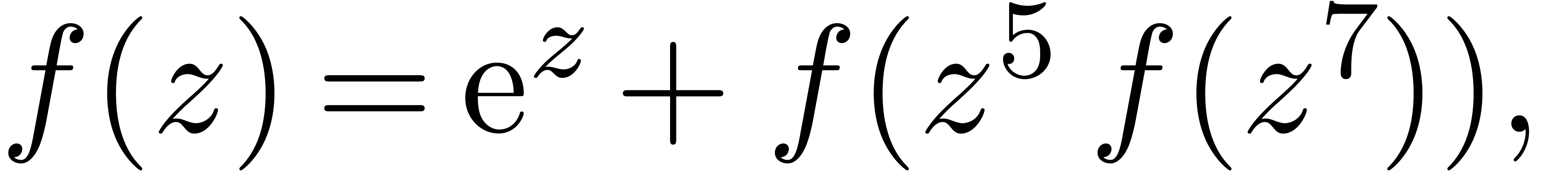

Remark

can be evaluated efficiently on small disks. Consequently, the Taylor

coefficients of  can be computed efficiently

using lemma 17.

can be computed efficiently

using lemma 17.

A. Aho, J. Hopcroft, and J. Ullman. The Design and Analysis of Computer Algorithms. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Massachusetts, 1974.

D.J. Bernstein. Composing power series over a finite ring in essentially linear time. JSC, 26(3):339–341, 1998.

R.P. Brent and H.T. Kung.  algorithms for composition and reversion of power series. In

J.F. Traub, editor, Analytic Computational Complexity,

Pittsburg, 1975. Proc. of a symposium on analytic computational

complexity held by Carnegie-Mellon University.

algorithms for composition and reversion of power series. In

J.F. Traub, editor, Analytic Computational Complexity,

Pittsburg, 1975. Proc. of a symposium on analytic computational

complexity held by Carnegie-Mellon University.

R.P. Brent and H.T. Kung. Fast algorithms for composition and reversion of multivariate power series. In Proc. Conf. Th. Comp. Sc., pages 149–158, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, August 1977. University of Waterloo.

R.P. Brent and H.T. Kung. Fast algorithms for manipulating formal power series. Journal of the ACM, 25:581–595, 1978.

Alin Bostan, Bruno Salvy, and Éric Schost. Power series composition and change of basis. In J. Rafael Sendra and Laureano González-Vega, editors, ISSAC, pages 269–276, Linz/Hagenberg, Austria, July 2008. ACM.

D.G. Cantor and E. Kaltofen. On fast multiplication of polynomials over arbitrary algebras. Acta Informatica, 28:693–701, 1991.

J.W. Cooley and J.W. Tukey. An algorithm for the machine calculation of complex Fourier series. Math. Computat., 19:297–301, 1965.

M. Fürer. Faster integer multiplication. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC 2007), pages 57–66, San Diego, California, 2007.

L. Kronecker. Grundzüge einer arithmetischen Theorie der algebraischen Grössen. Jour. für die reine und ang. Math., 92:1–122, 1882.

A. Schönhage. Asymptotically fast algorithms for the numerical multiplication and division of polynomials with complex coefficients. In J. Calmet, editor, EUROCAM '82: European Computer Algebra Conference, volume 144 of Lect. Notes Comp. Sci., pages 3–15, Marseille, France, April 1982. Springer.

A. Schönhage and V. Strassen. Schnelle Multiplikation grosser Zahlen. Computing, 7:281–292, 1971.

J. van der Hoeven. Relax, but don't be too lazy. JSC, 34:479–542, 2002.

Joris van der Hoeven. New algorithms for relaxed multiplication. JSC, 42(8):792–802, 2007.