Fast modular composition using

spiroids  |

|

| Preliminary version of December 5, 2025 |

|

. Grégoire

Lecerf has been supported by the French ANR-22-CE48-0016

NODE project. Joris van der Hoeven has been supported by an

ERC-2023-ADG grant for the ODELIX project (number 101142171).

. Grégoire

Lecerf has been supported by the French ANR-22-CE48-0016

NODE project. Joris van der Hoeven has been supported by an

ERC-2023-ADG grant for the ODELIX project (number 101142171).

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. |

|

. This article has

been written using GNU TeXmacs [8].

. This article has

been written using GNU TeXmacs [8].

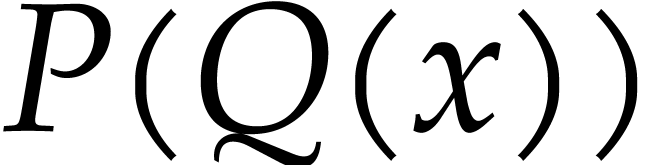

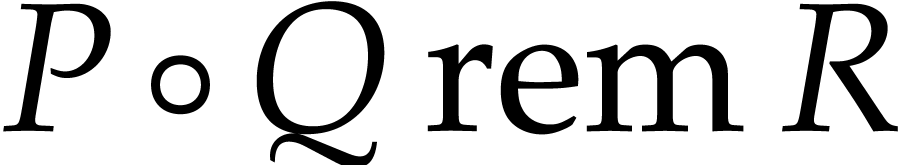

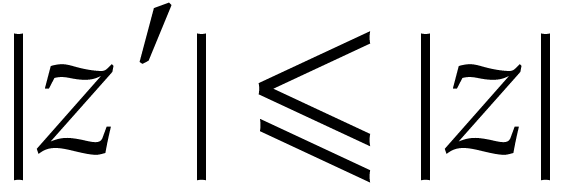

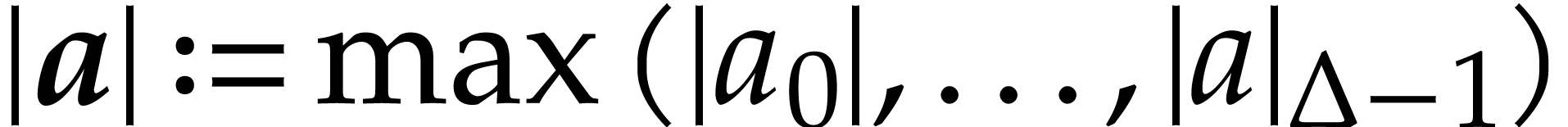

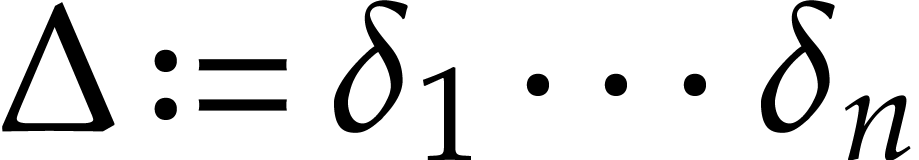

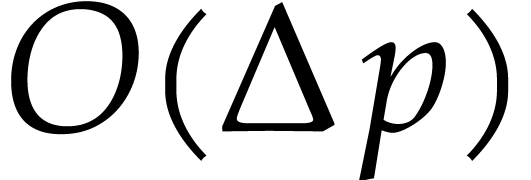

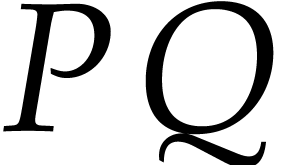

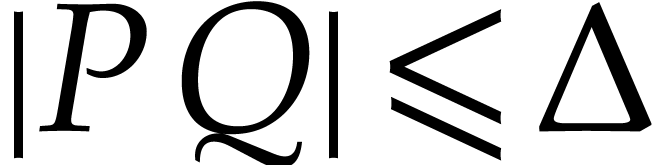

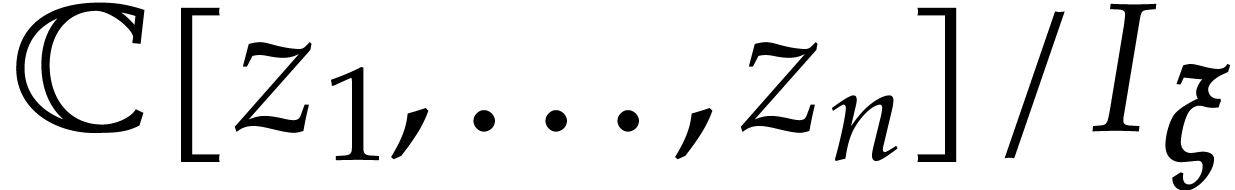

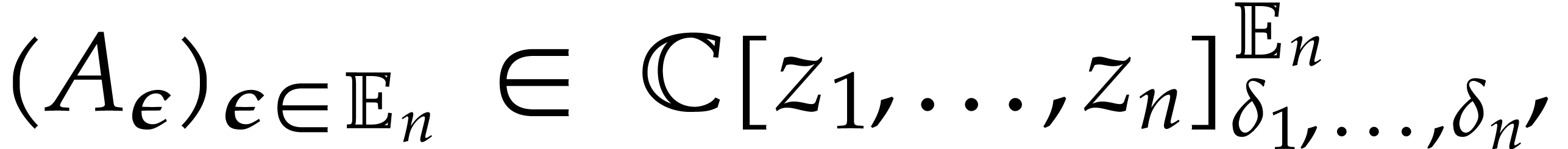

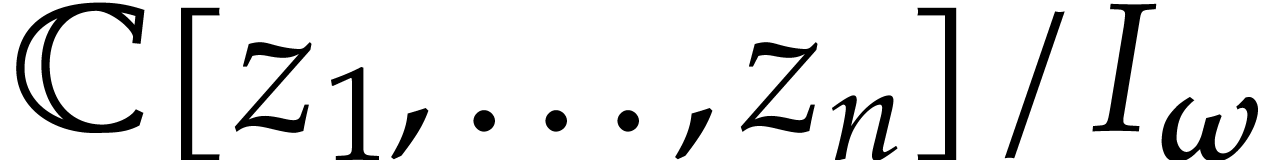

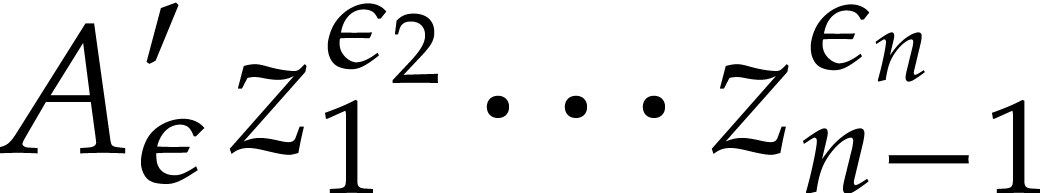

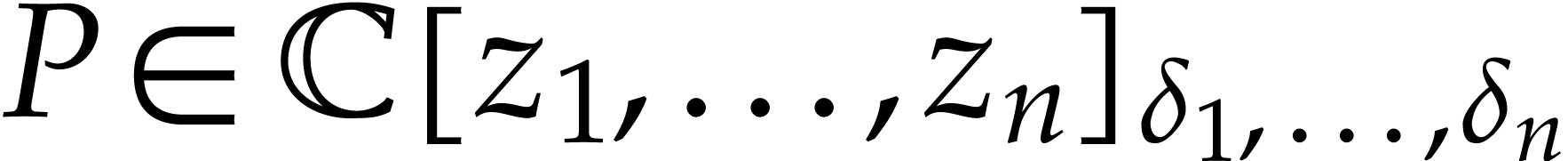

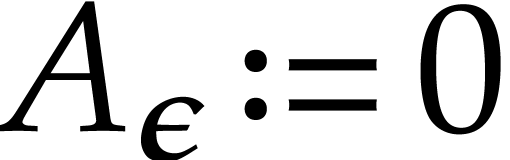

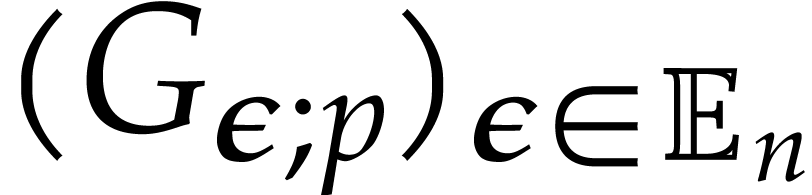

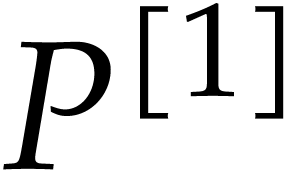

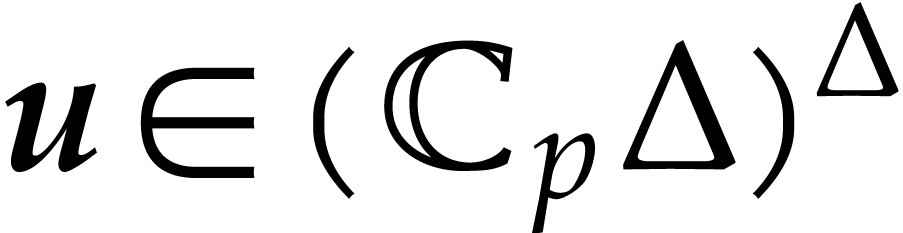

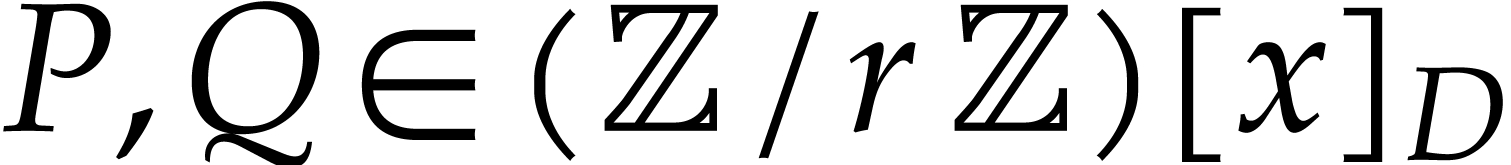

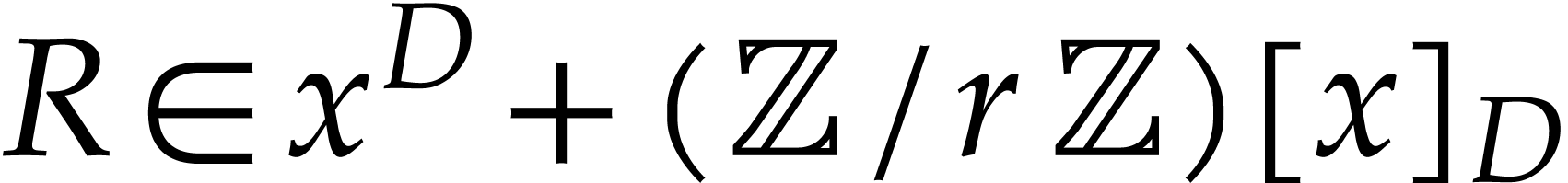

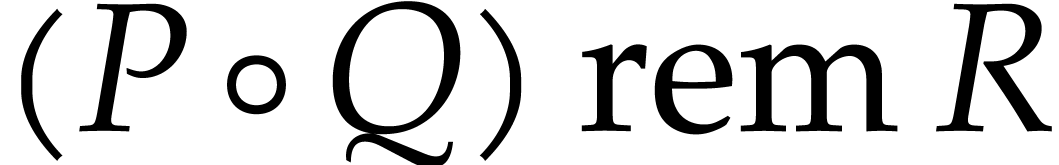

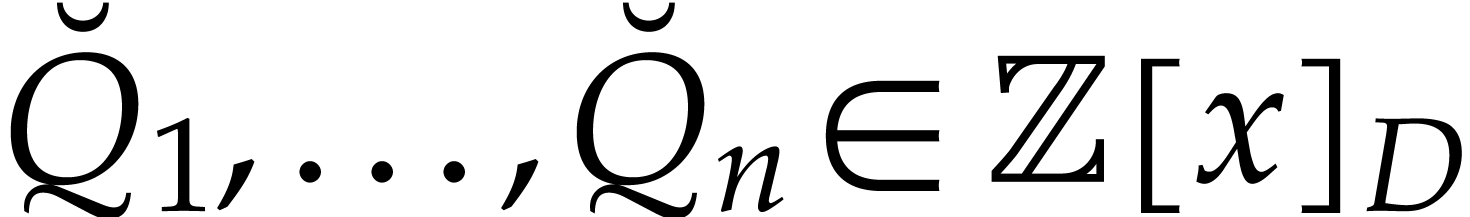

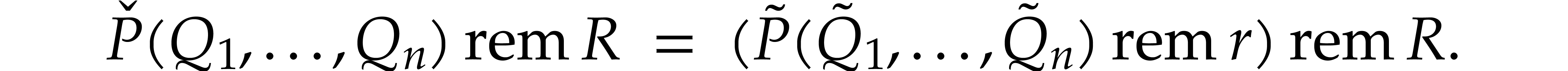

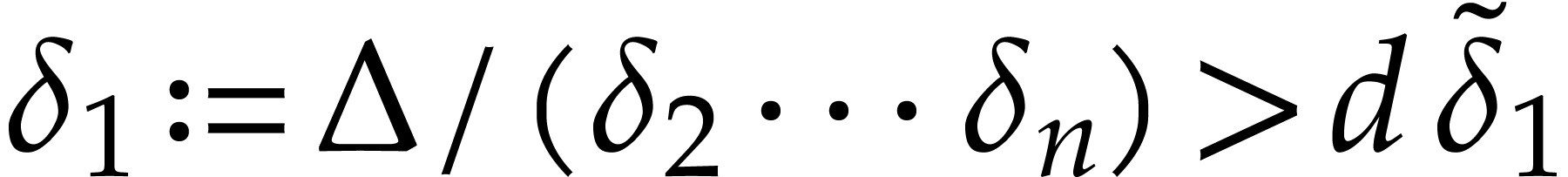

Given three univariate polynomials |

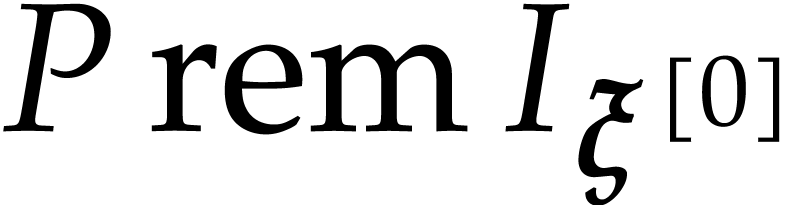

Let  be an effective commutative ring, so that we

have algorithms for the ring operations. Given a monic polynomial

be an effective commutative ring, so that we

have algorithms for the ring operations. Given a monic polynomial  of degree

of degree  and polynomials

and polynomials

and

and  in

in  of degree

of degree  the computation of the remainder of

the computation of the remainder of

in the division by

in the division by  ,

written

,

written  , is called the

problem of modular composition. Modular composition is a

central operation in computer algebra, especially for irreducible

polynomial factorization; see [12] for instance. It is

still unknown whether modular composition can be achieved in time nearly

linear in

, is called the

problem of modular composition. Modular composition is a

central operation in computer algebra, especially for irreducible

polynomial factorization; see [12] for instance. It is

still unknown whether modular composition can be achieved in time nearly

linear in  or not for any ground ring

or not for any ground ring  .

.

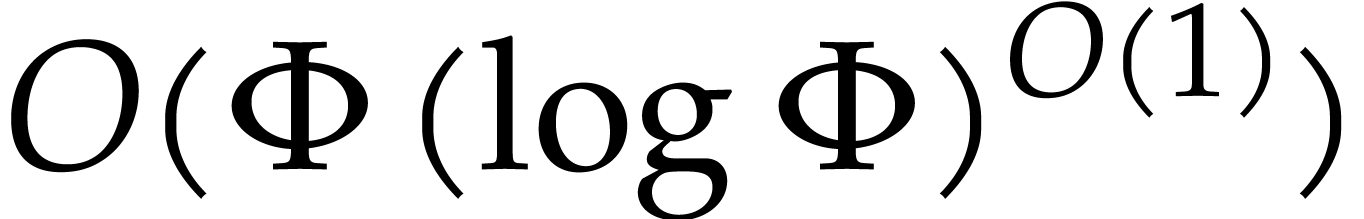

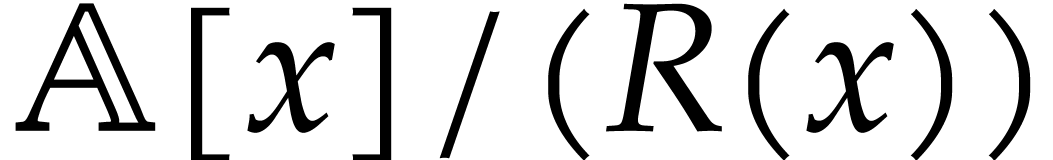

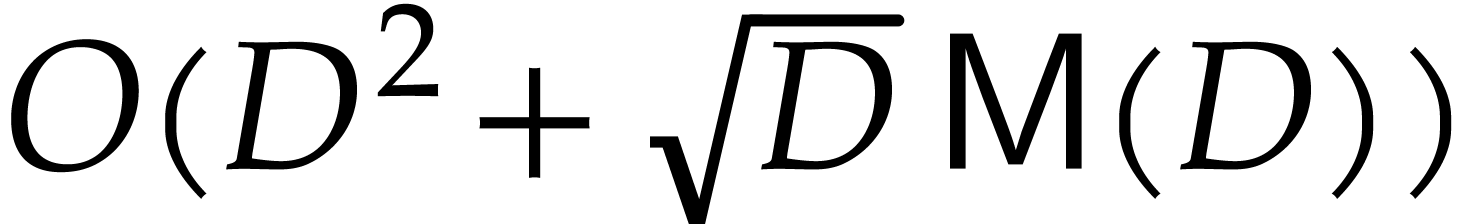

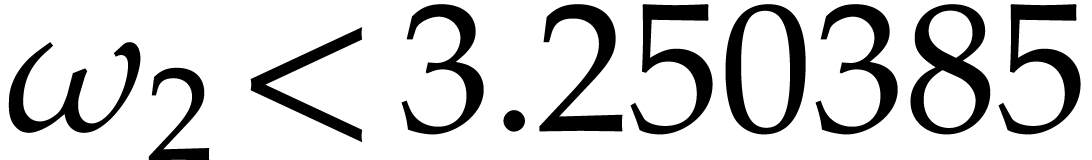

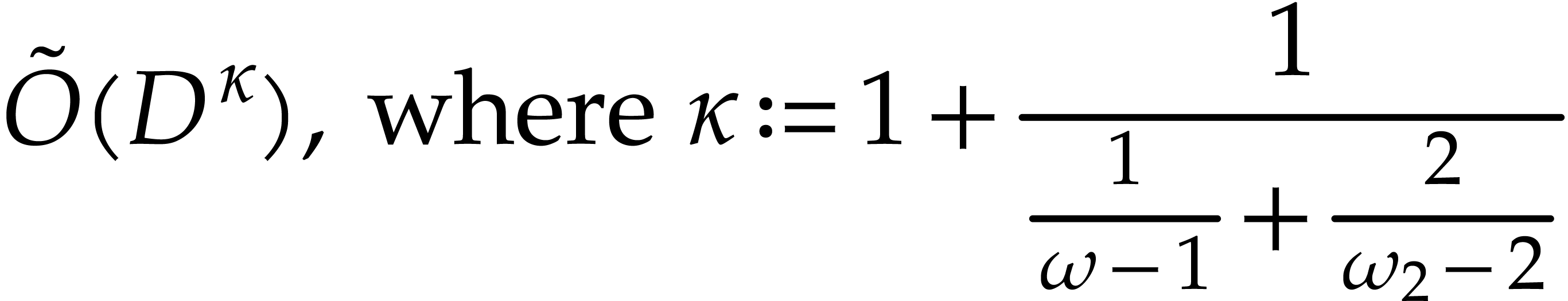

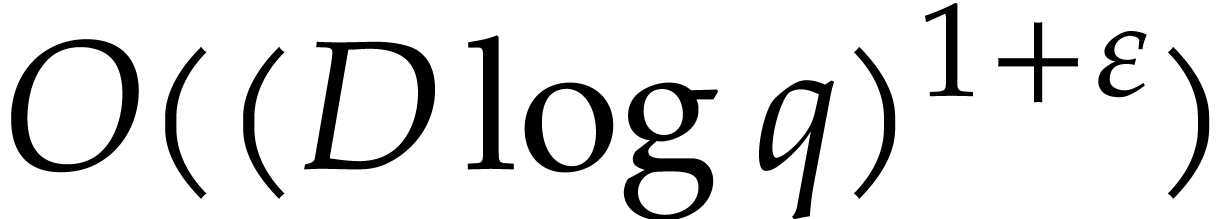

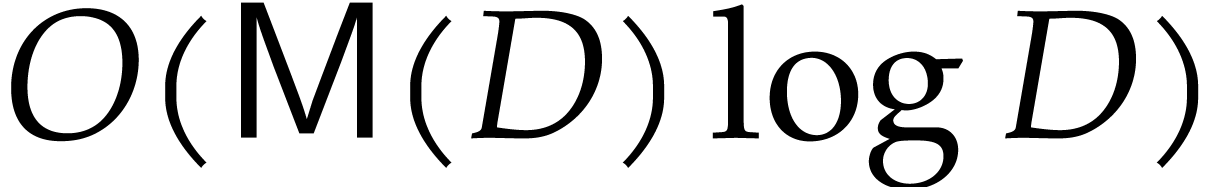

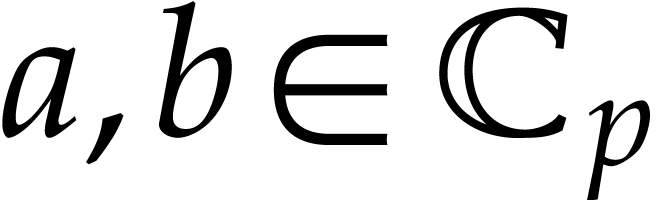

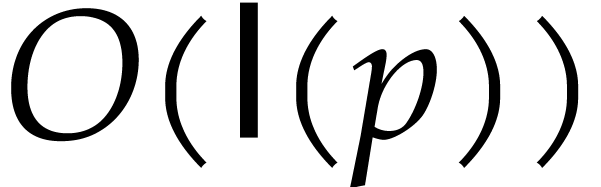

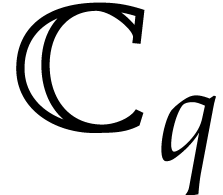

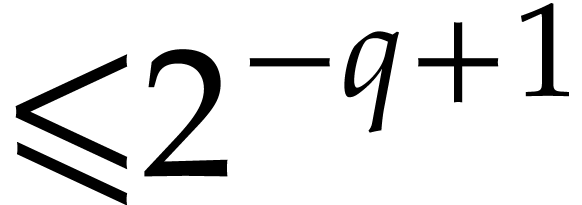

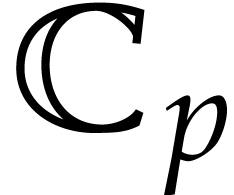

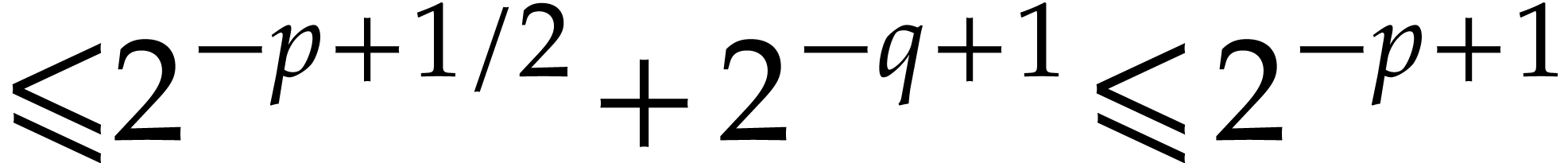

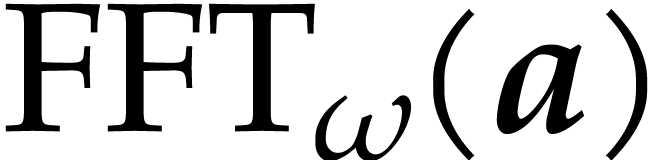

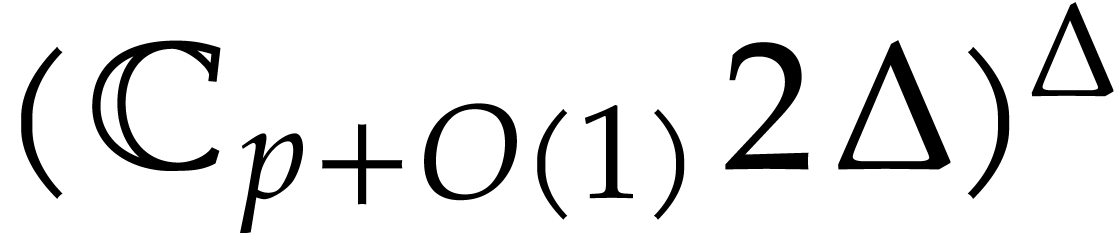

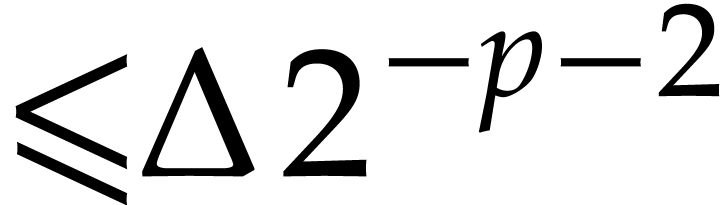

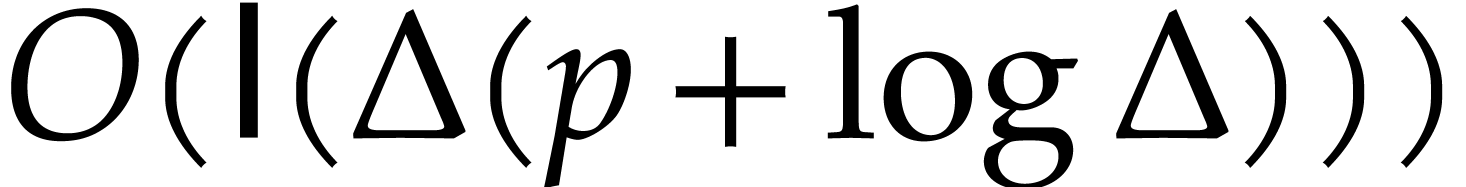

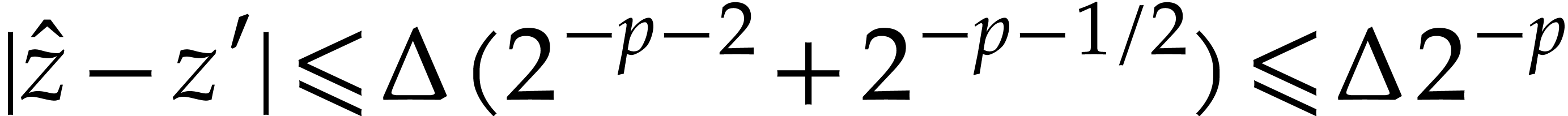

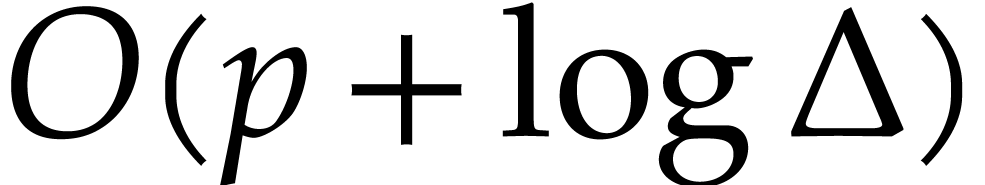

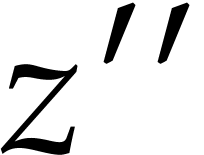

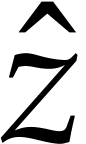

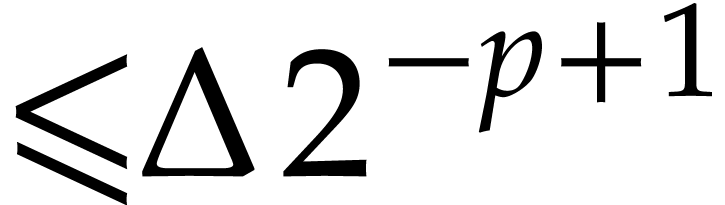

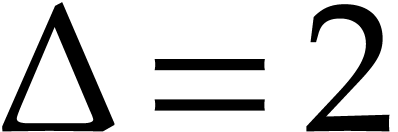

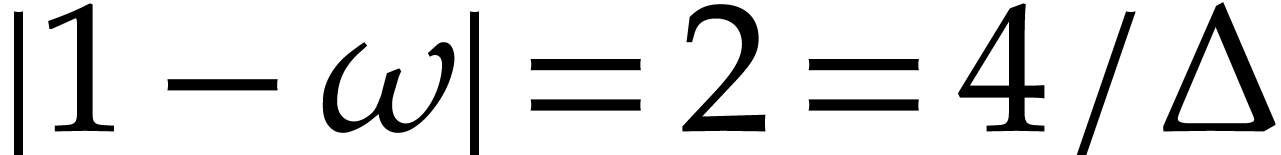

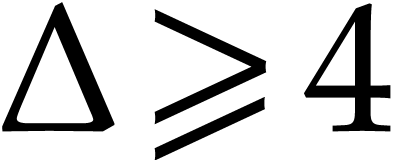

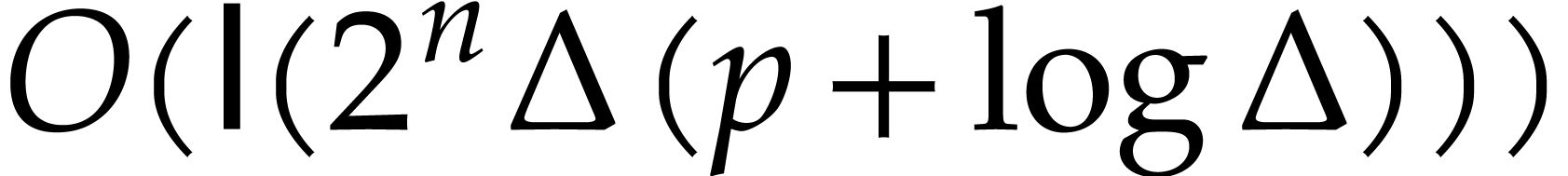

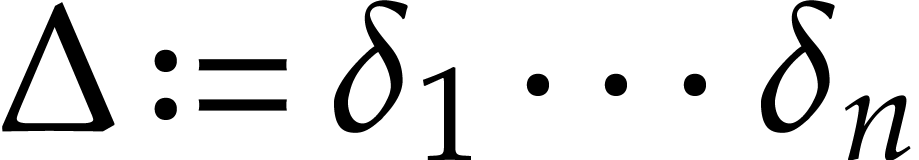

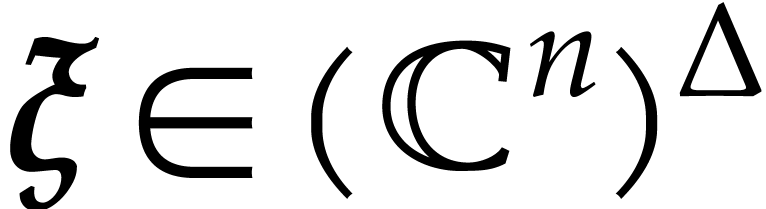

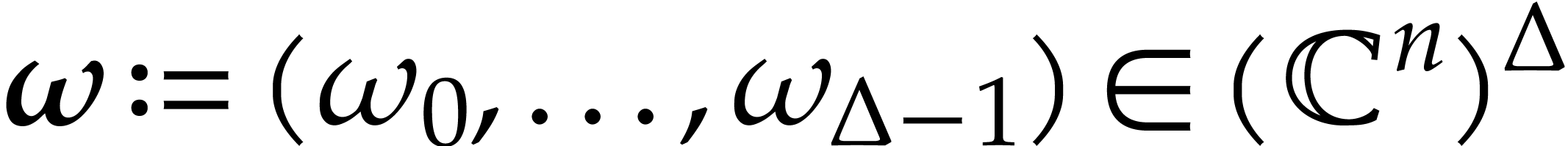

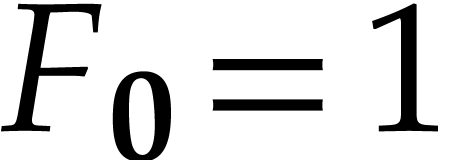

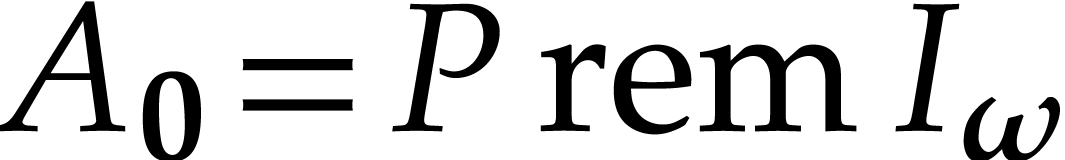

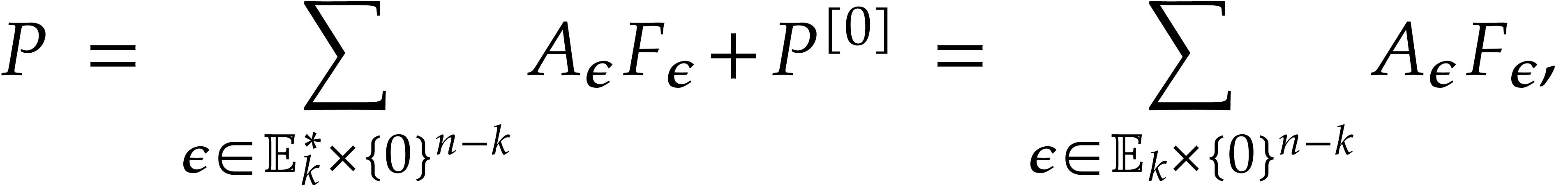

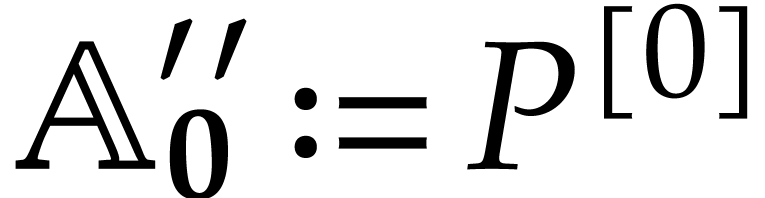

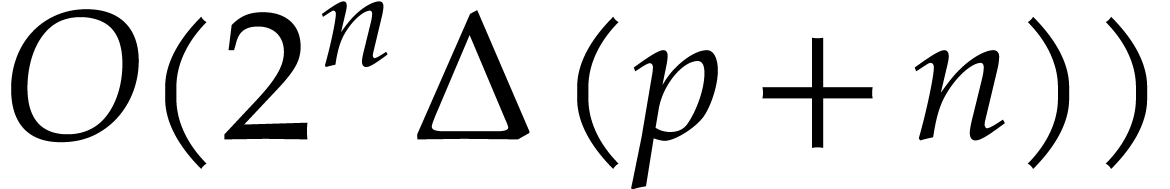

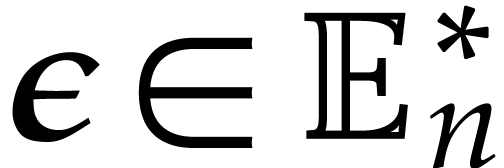

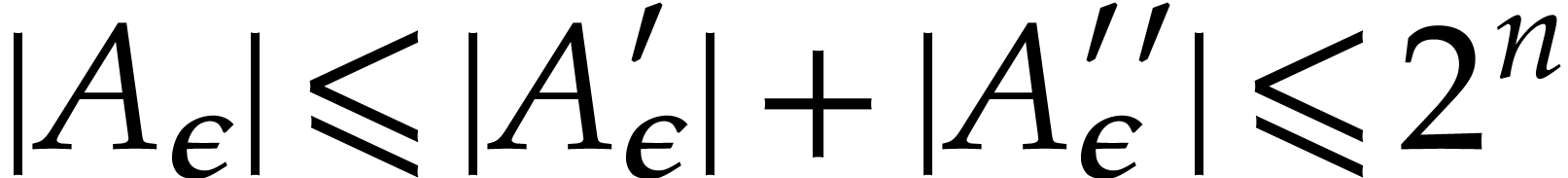

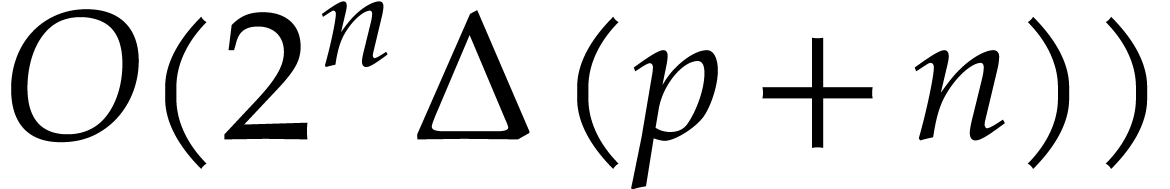

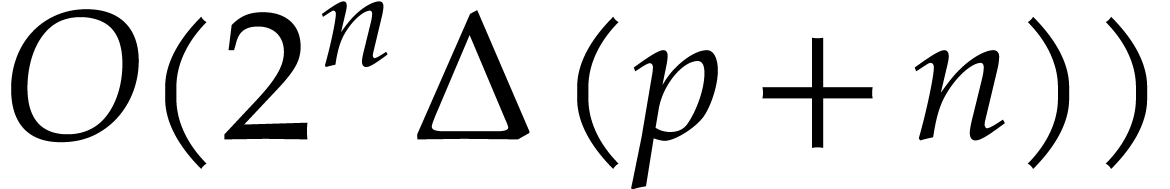

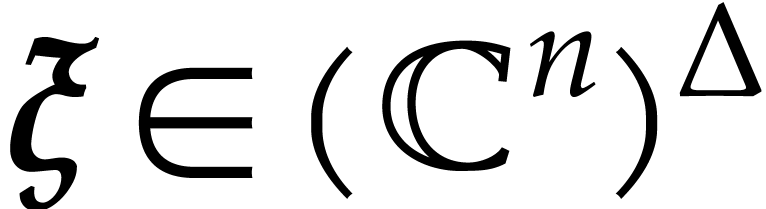

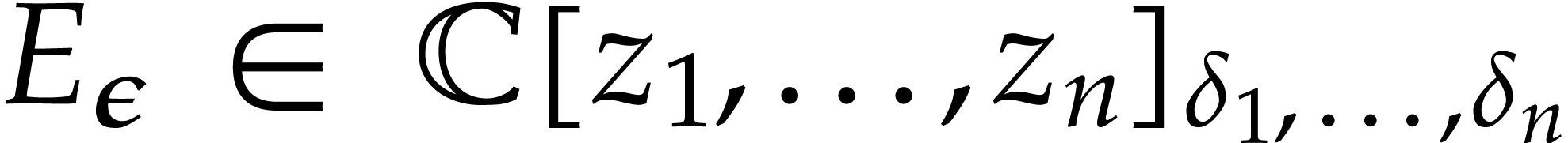

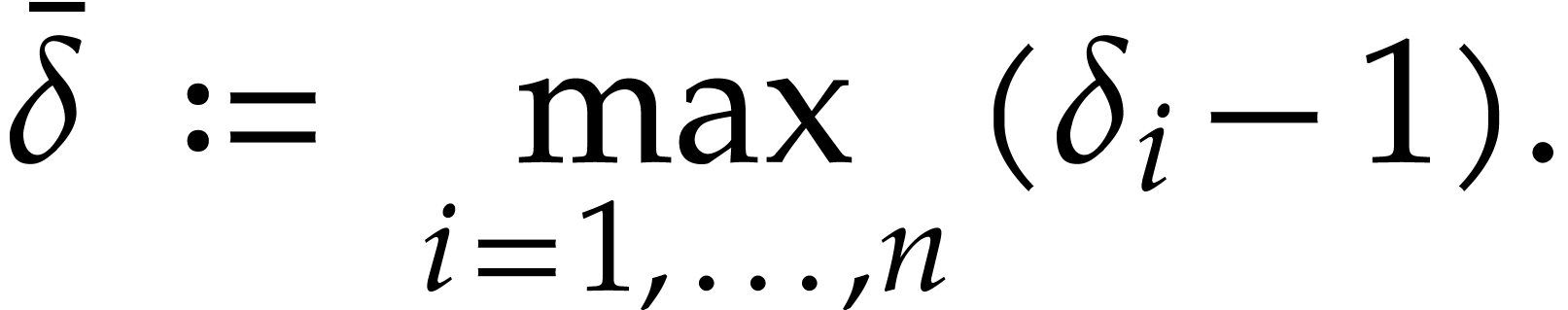

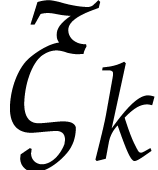

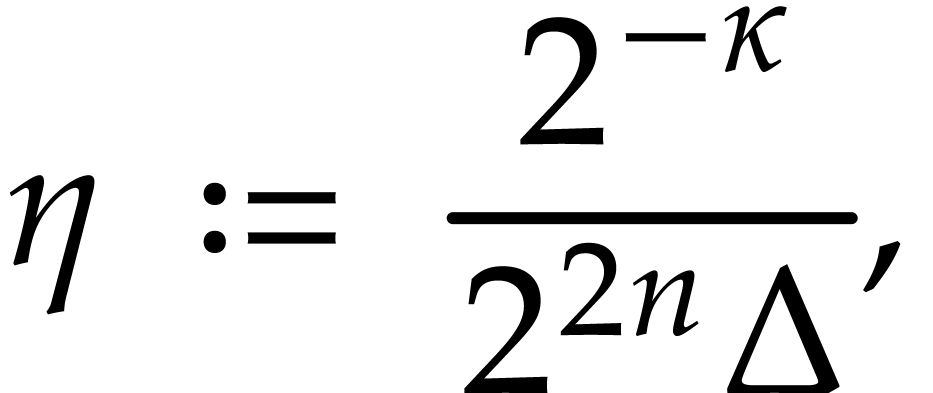

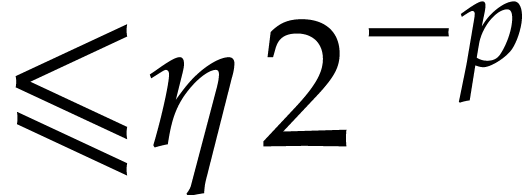

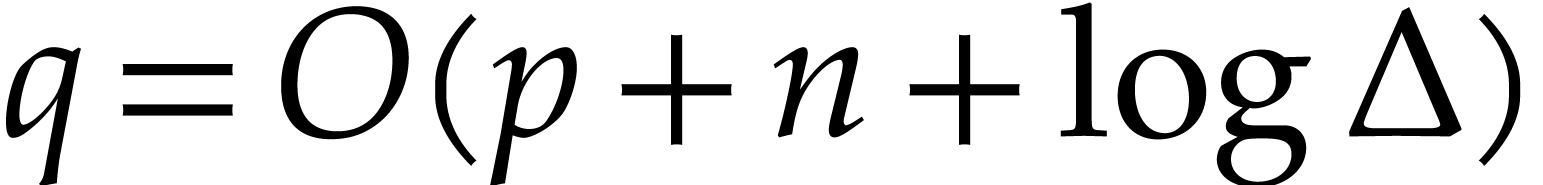

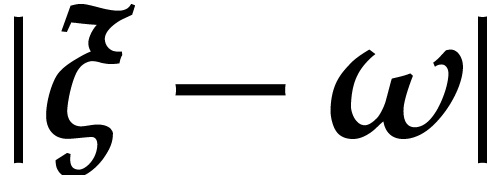

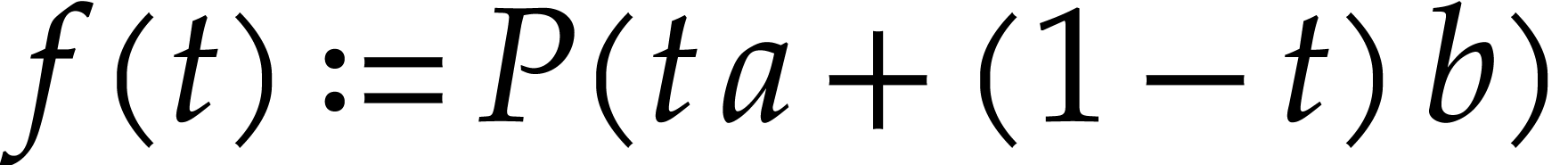

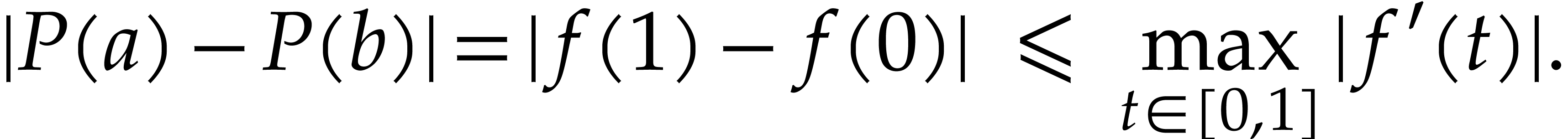

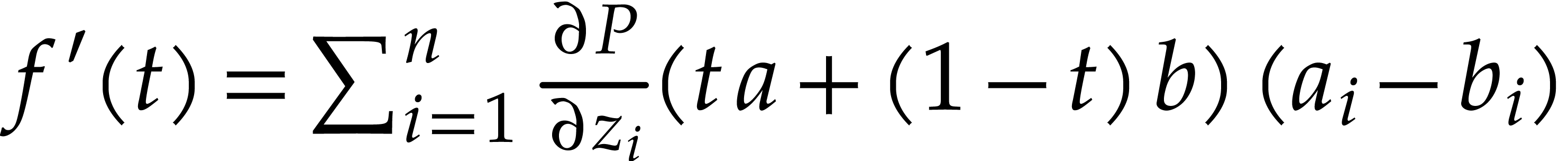

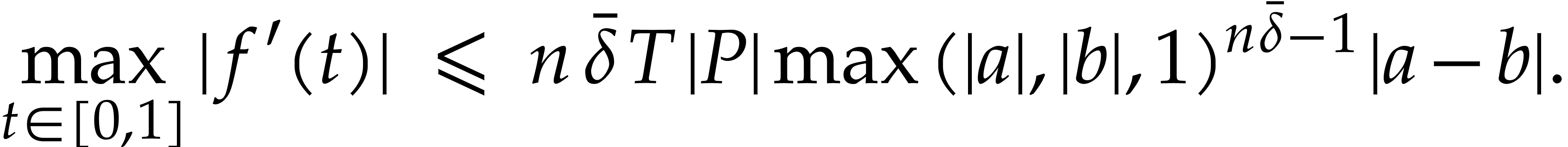

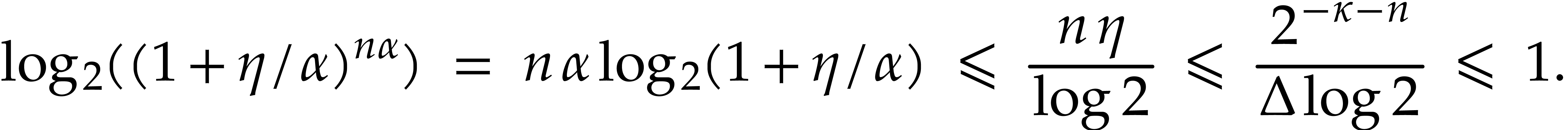

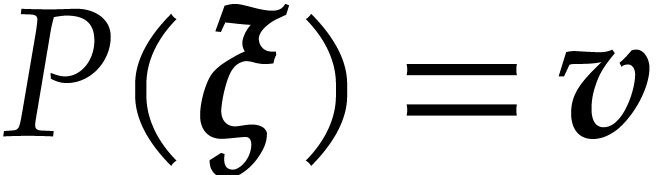

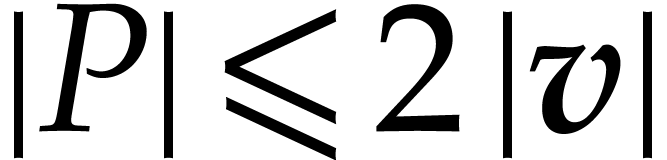

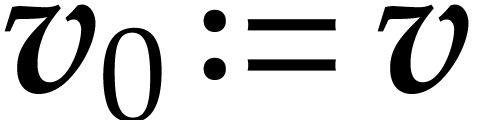

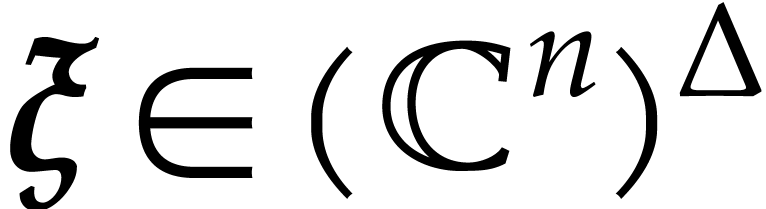

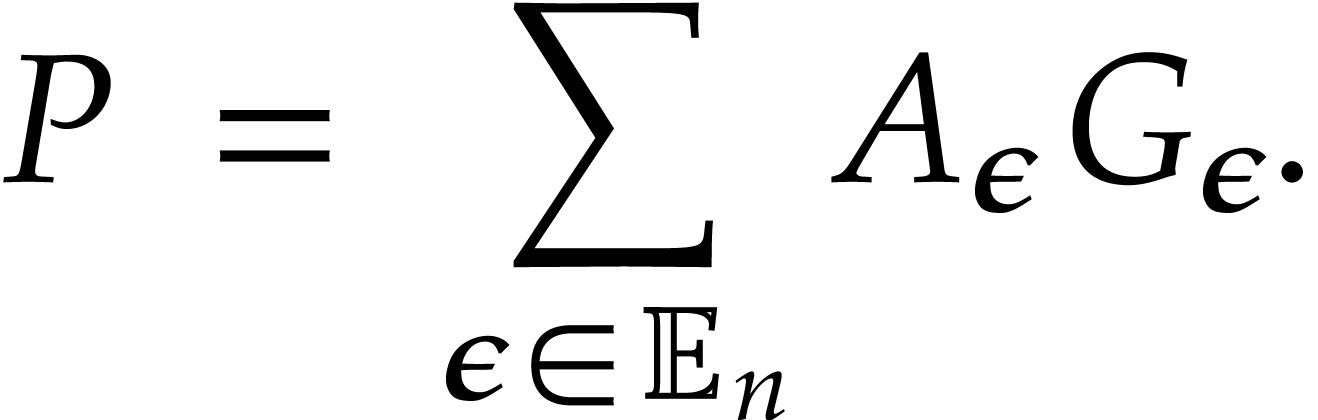

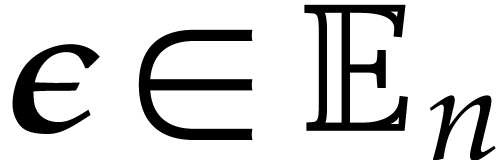

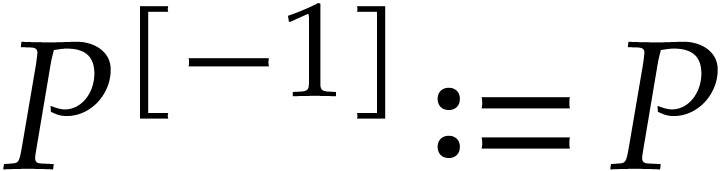

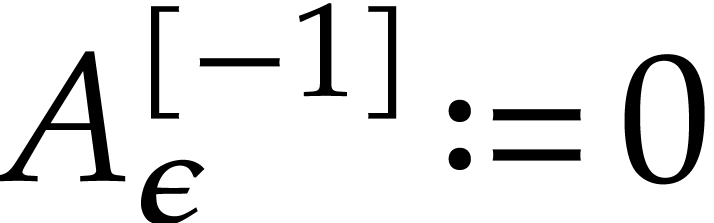

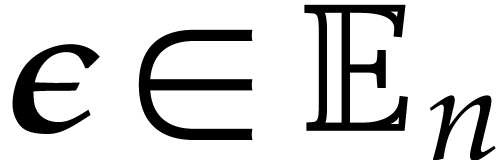

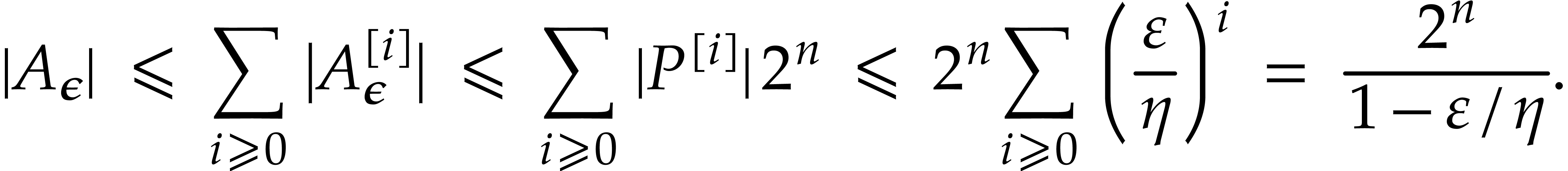

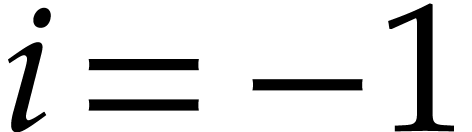

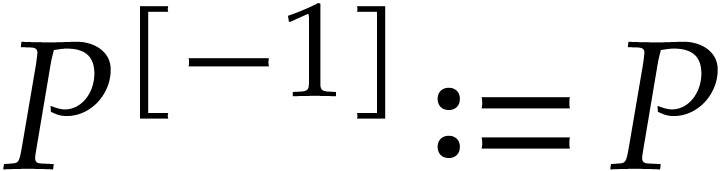

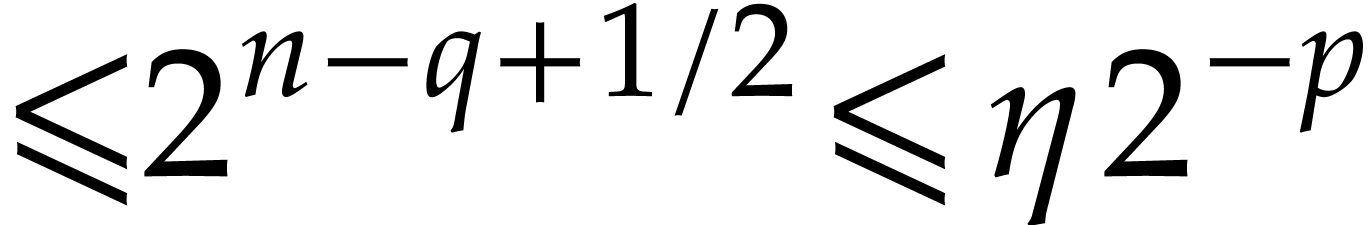

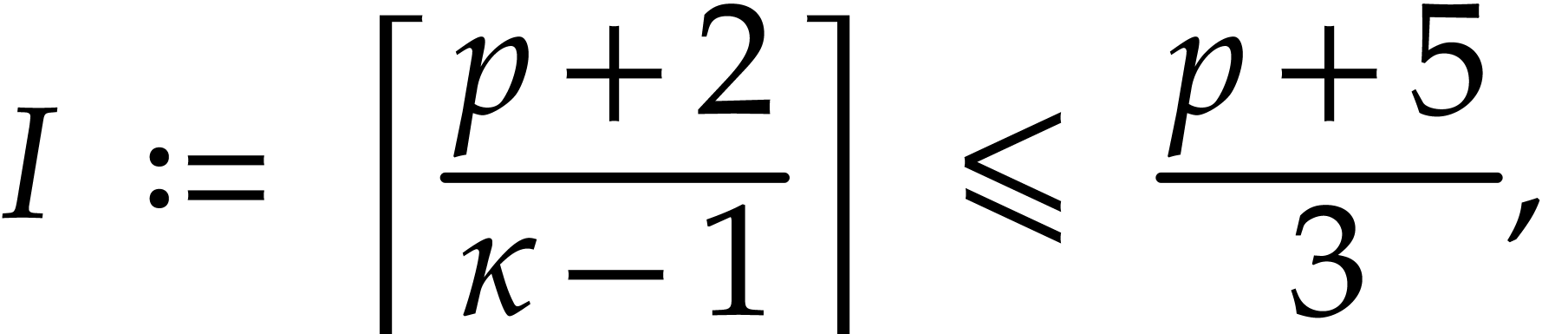

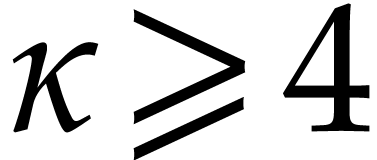

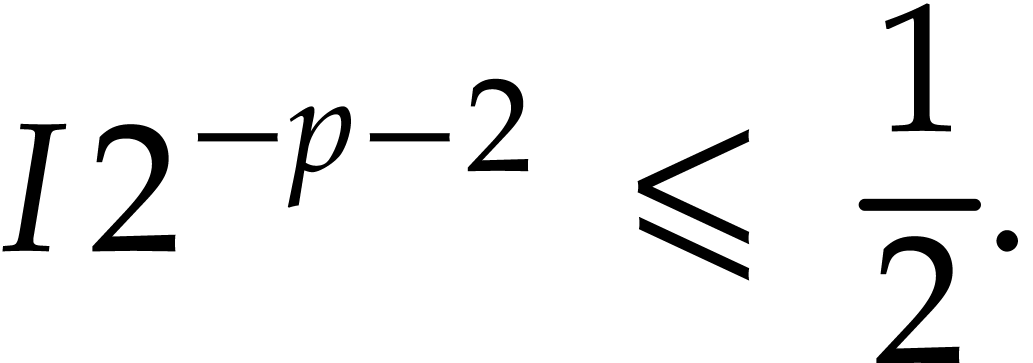

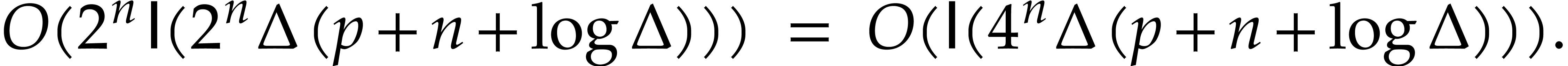

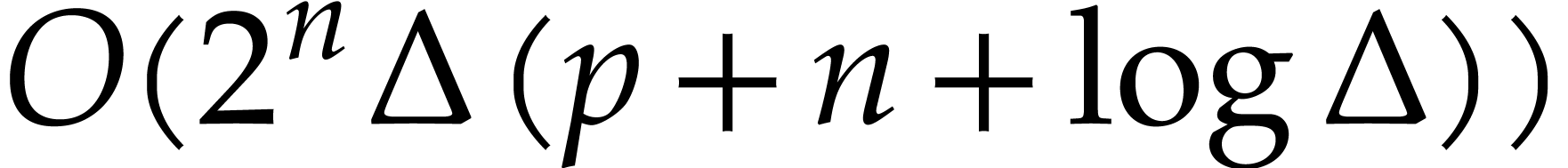

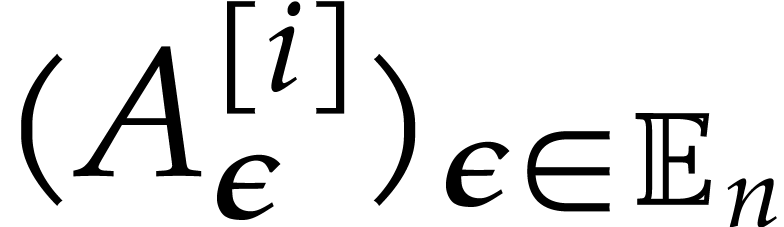

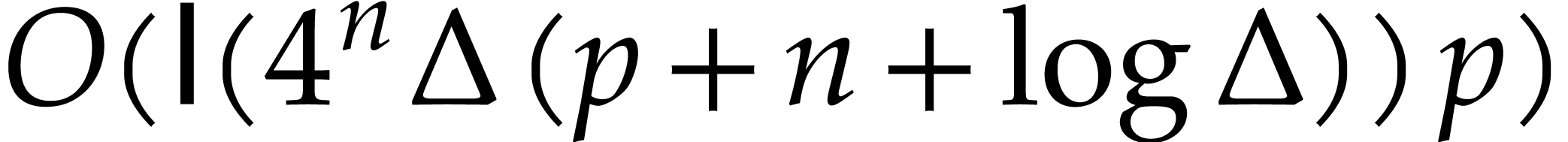

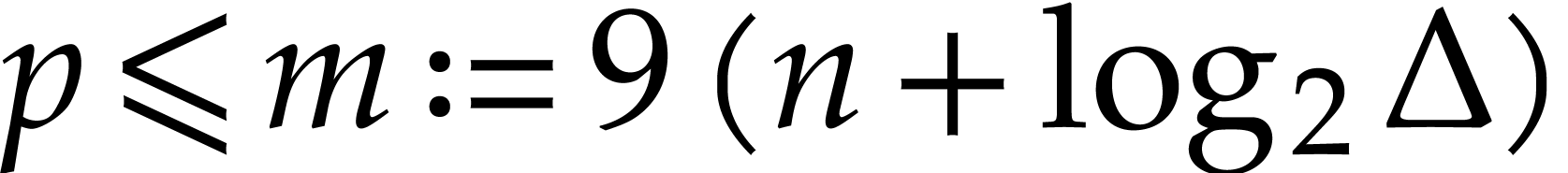

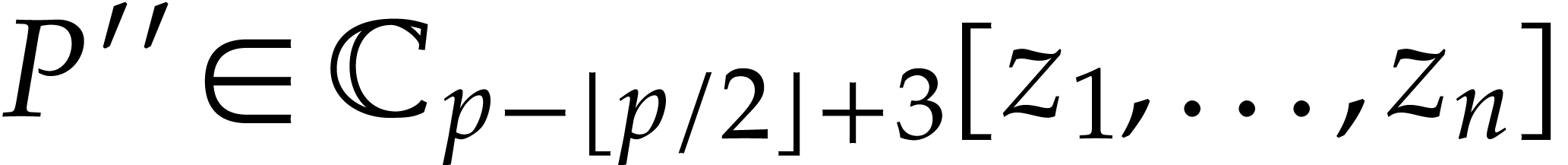

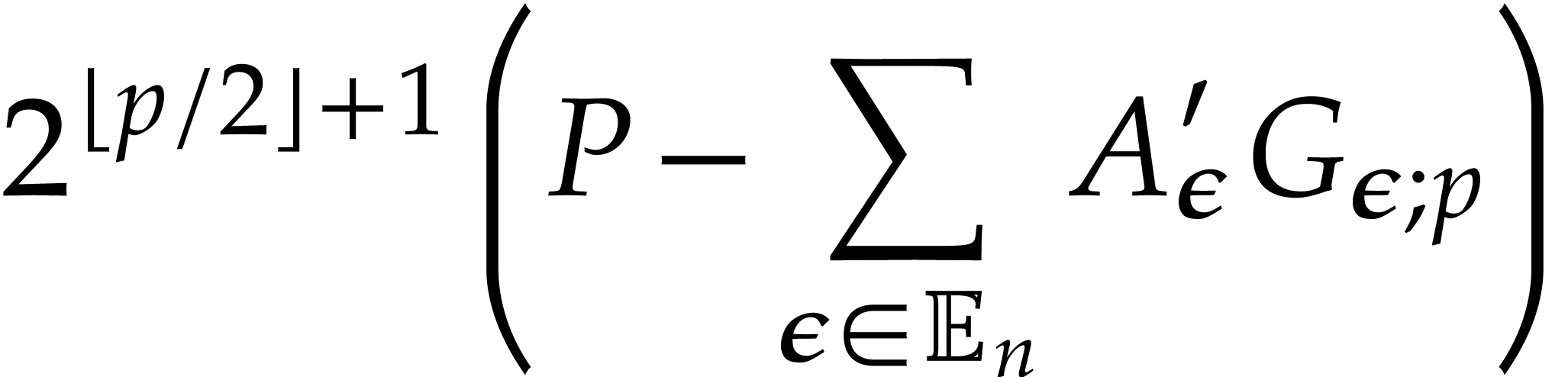

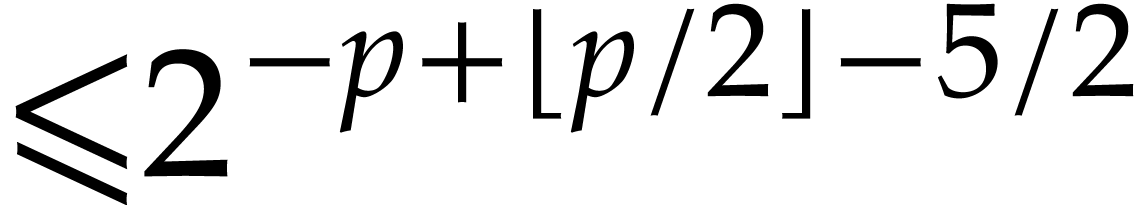

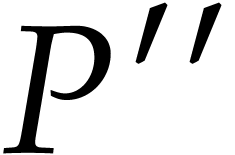

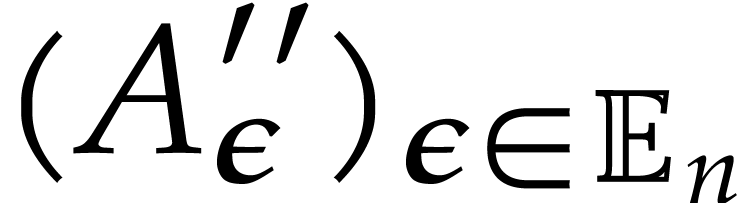

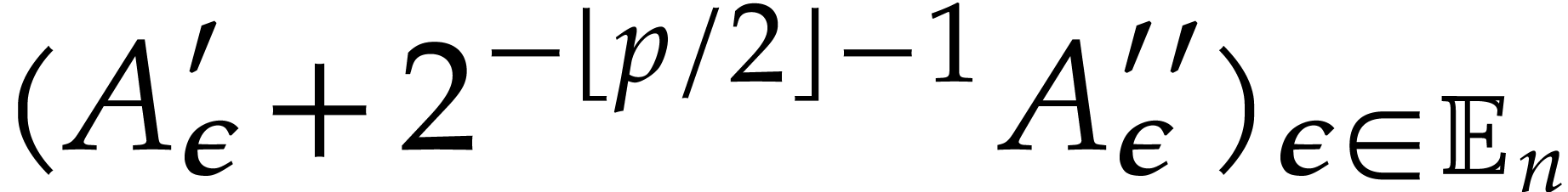

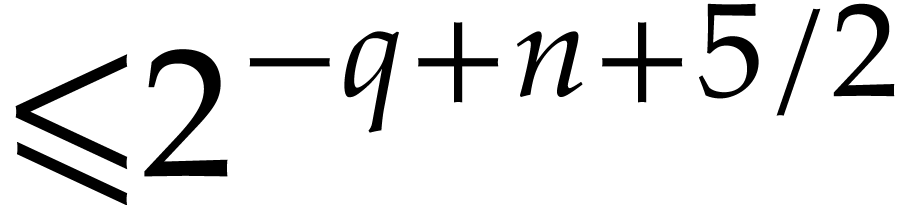

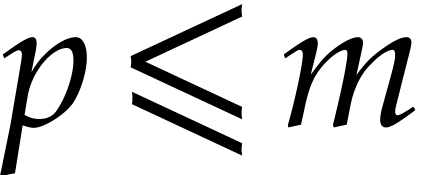

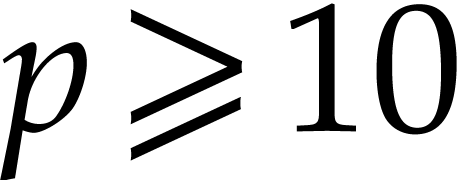

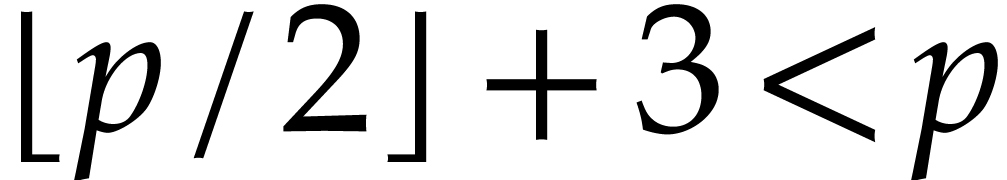

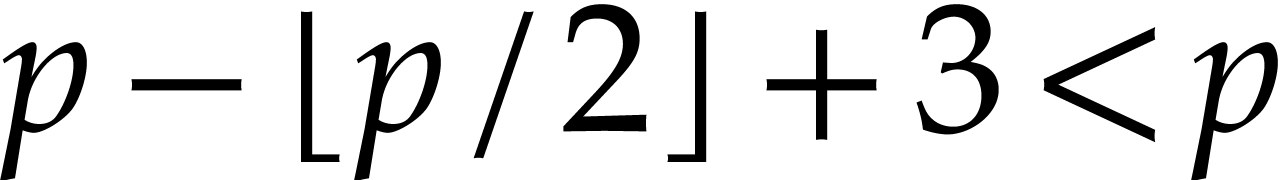

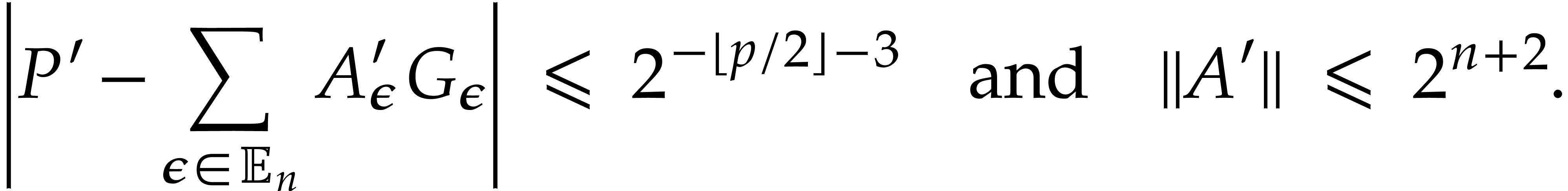

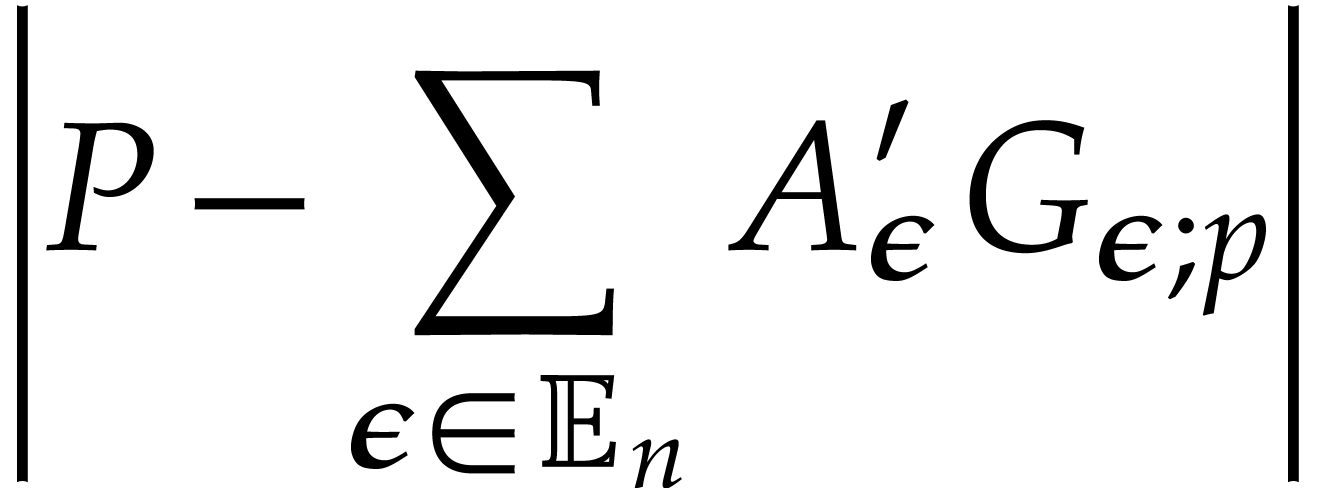

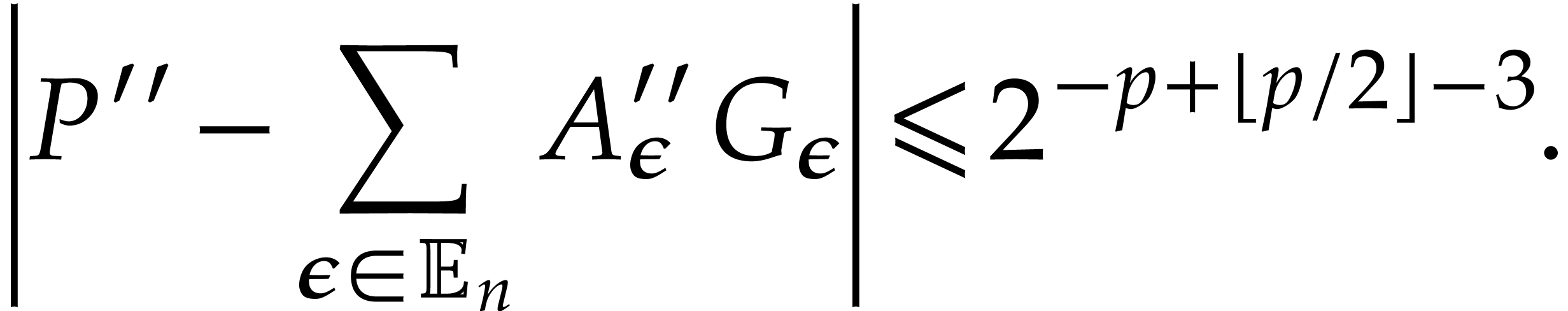

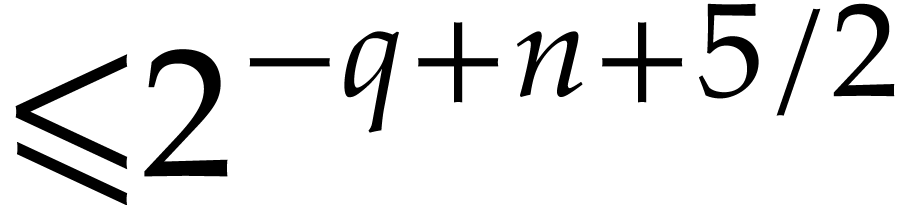

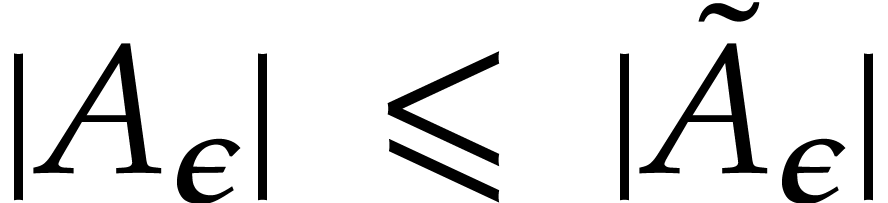

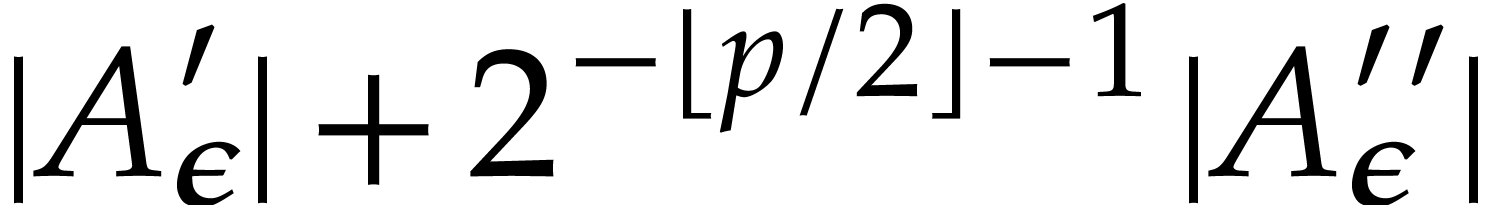

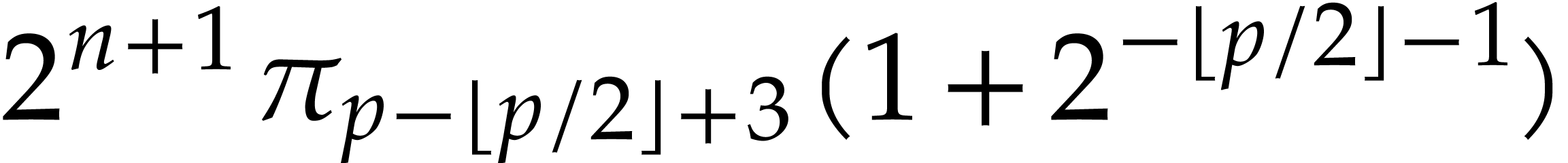

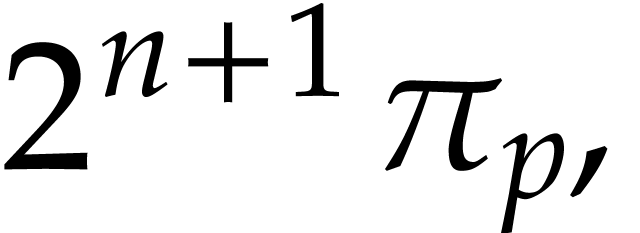

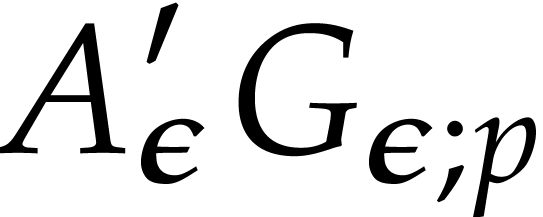

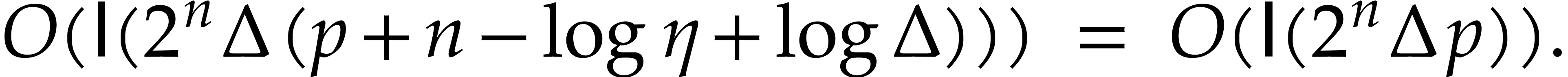

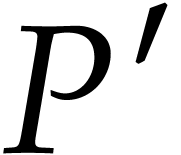

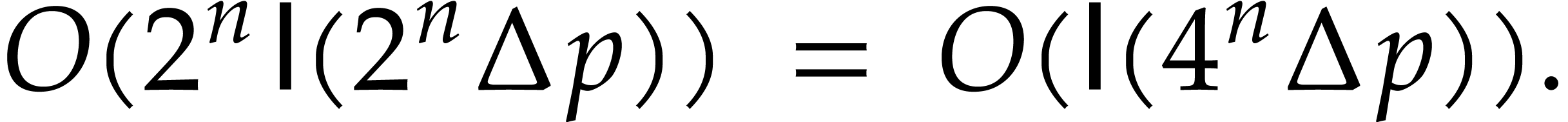

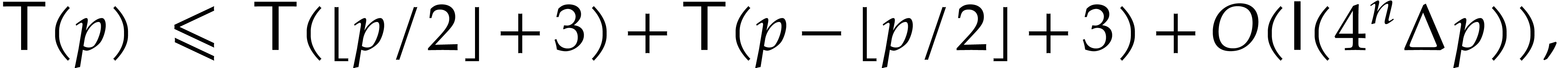

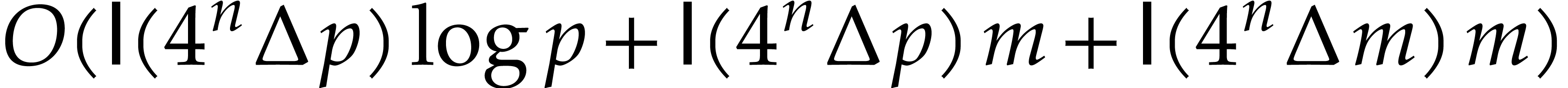

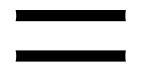

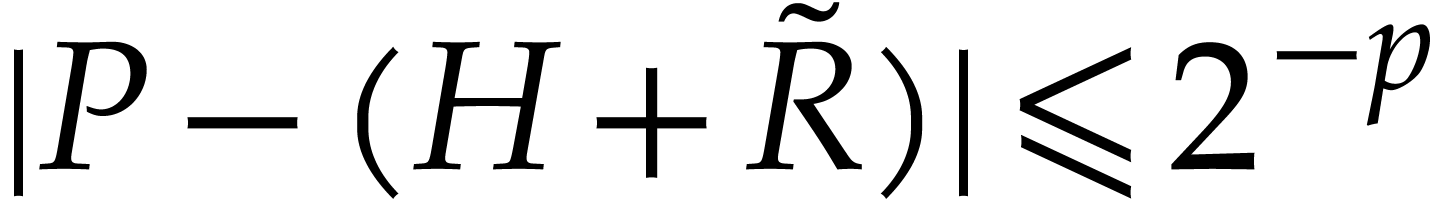

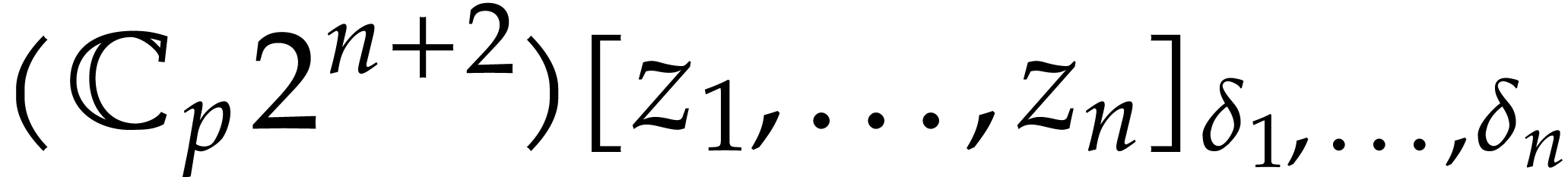

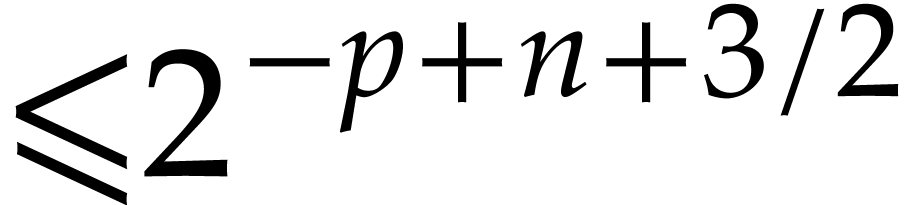

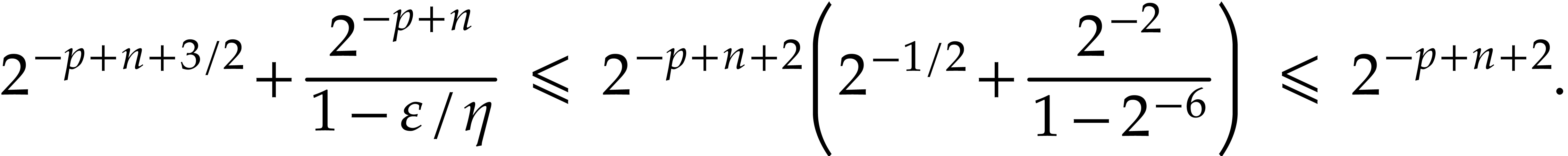

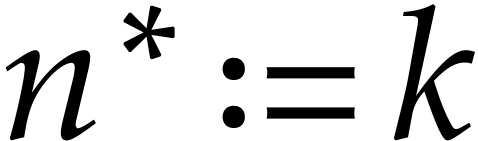

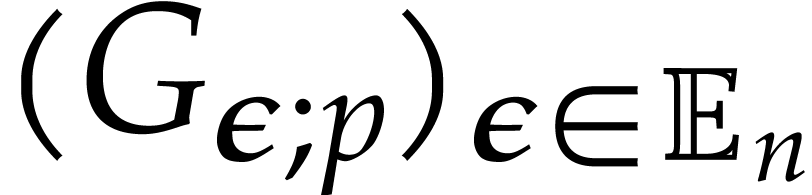

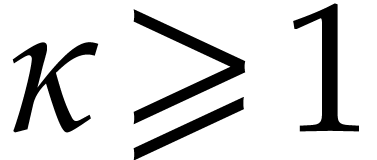

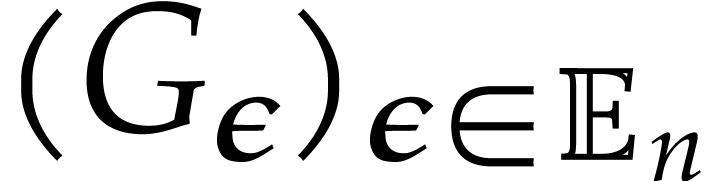

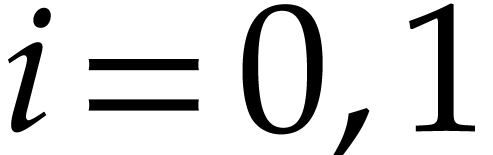

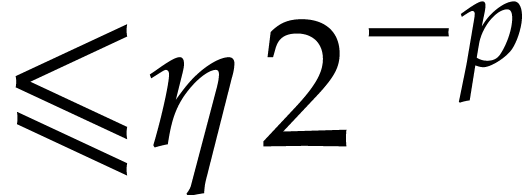

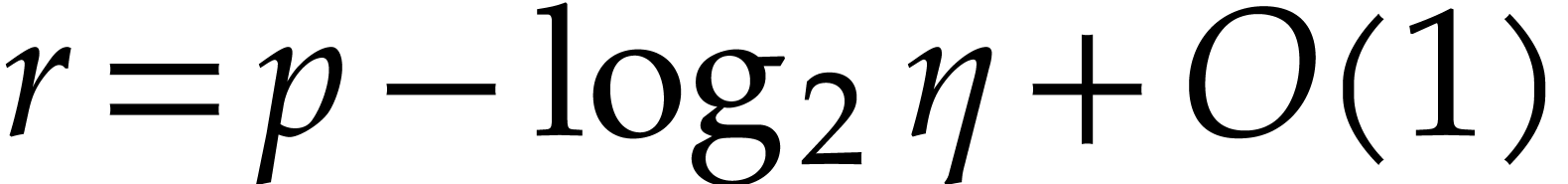

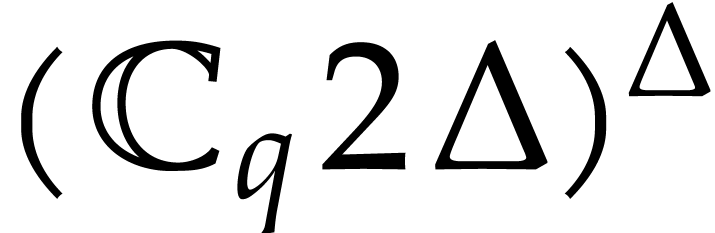

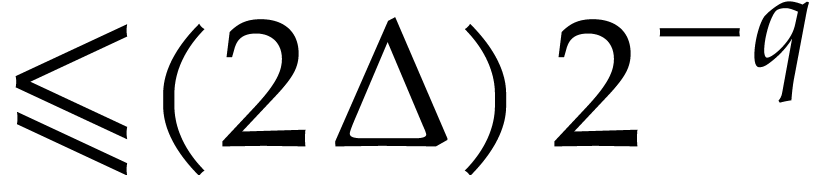

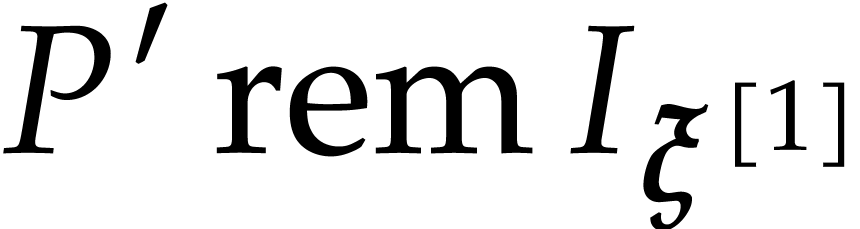

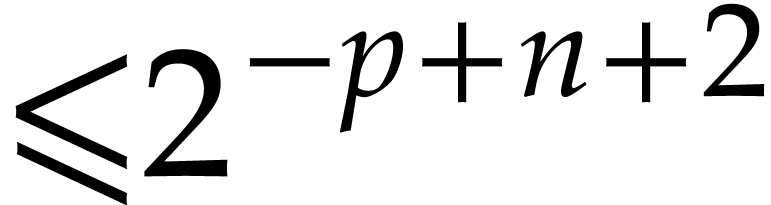

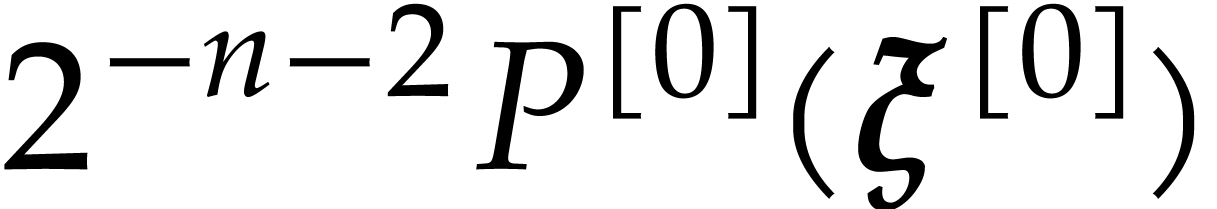

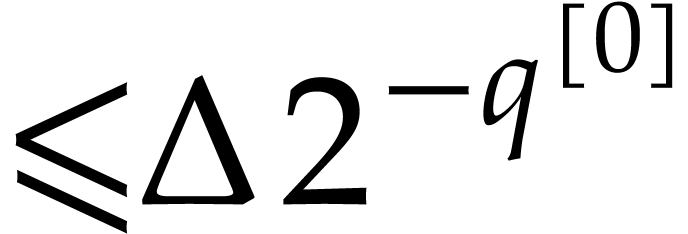

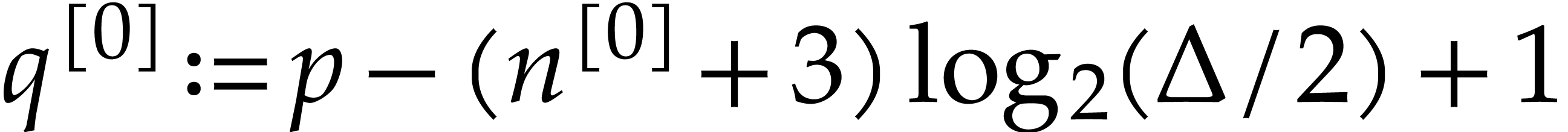

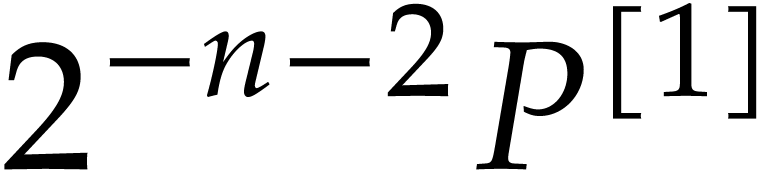

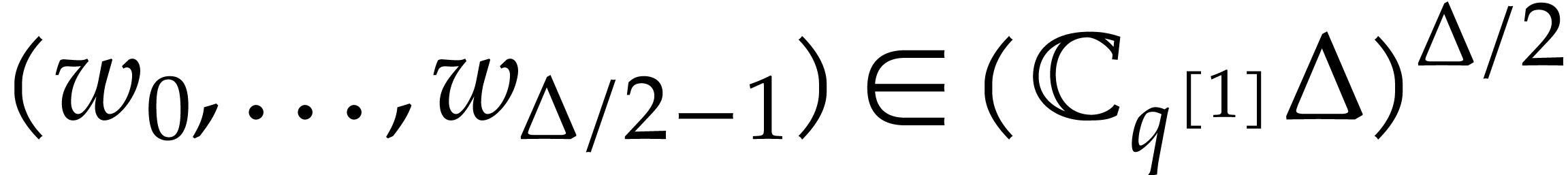

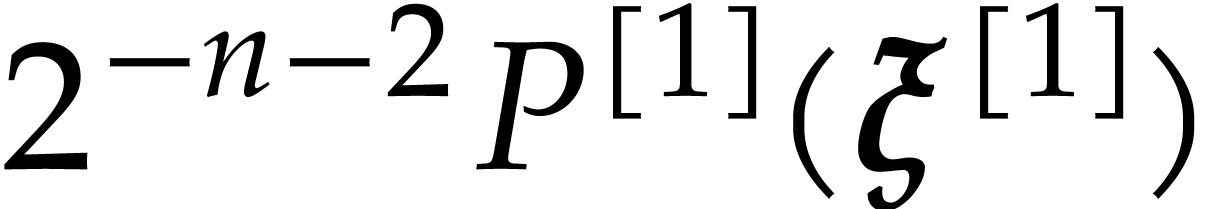

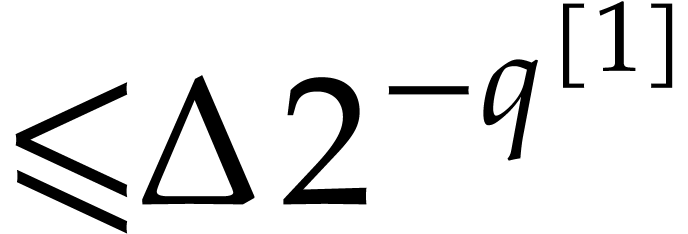

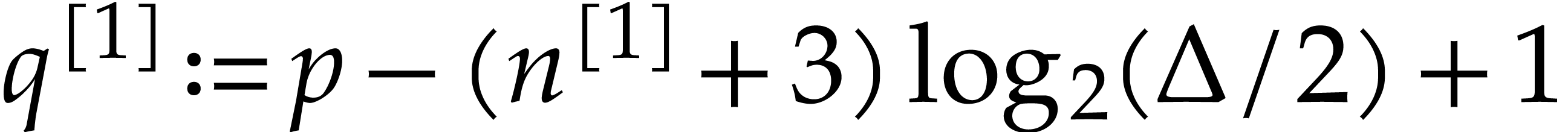

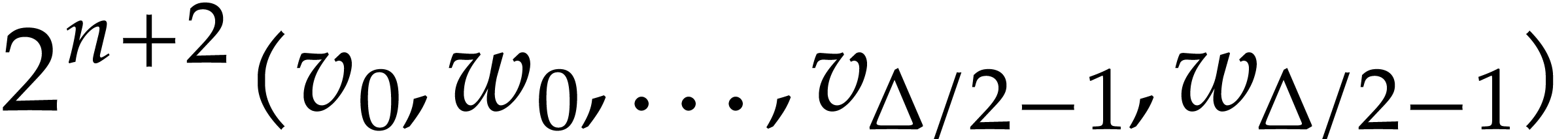

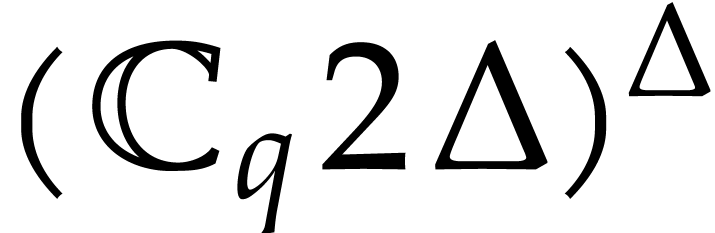

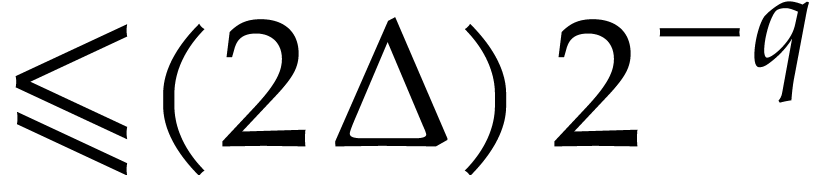

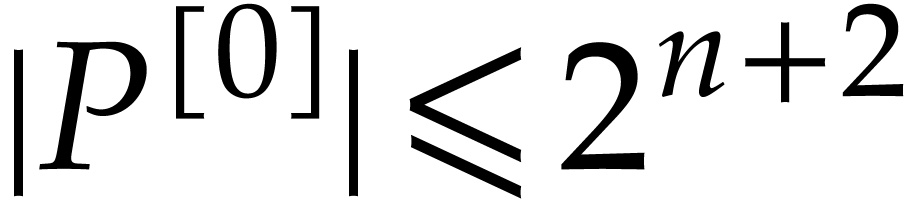

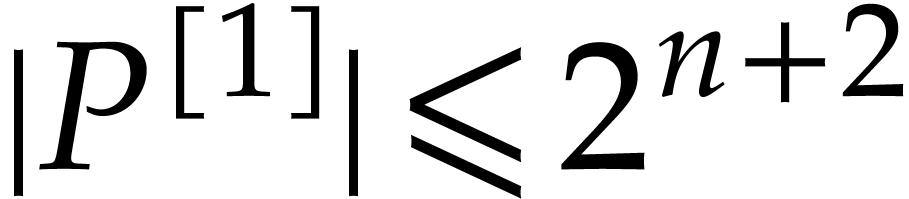

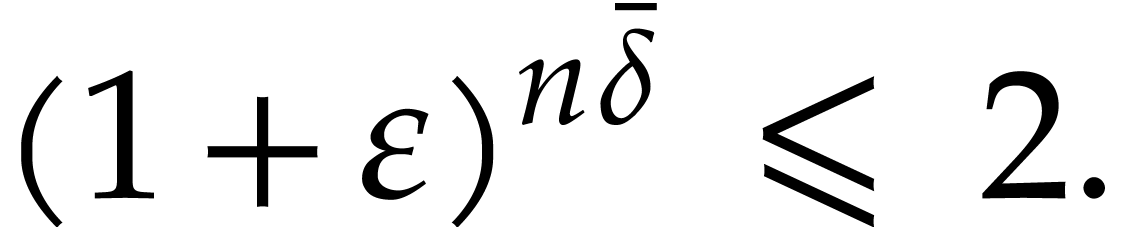

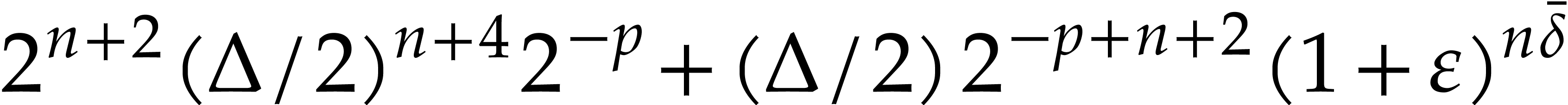

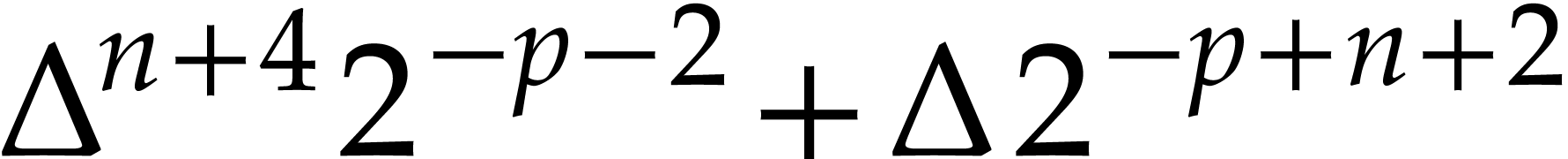

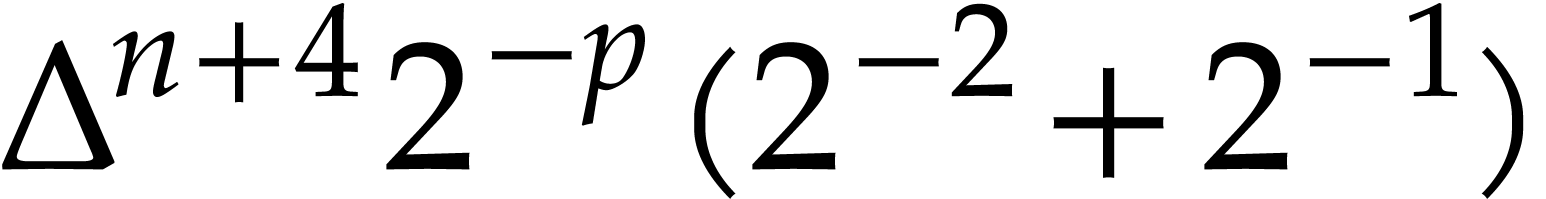

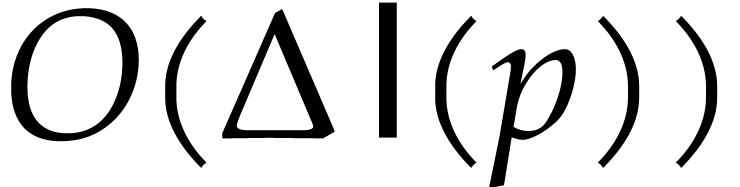

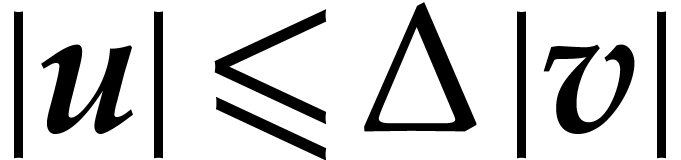

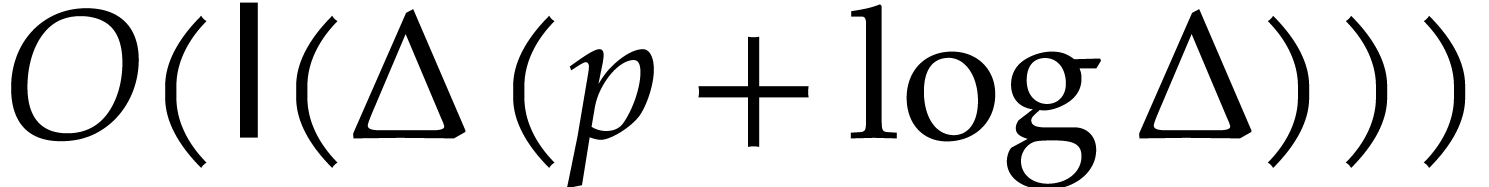

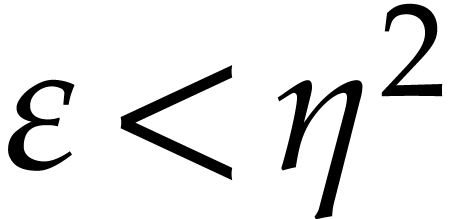

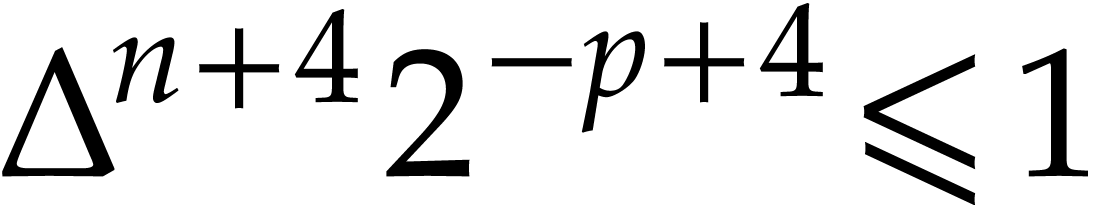

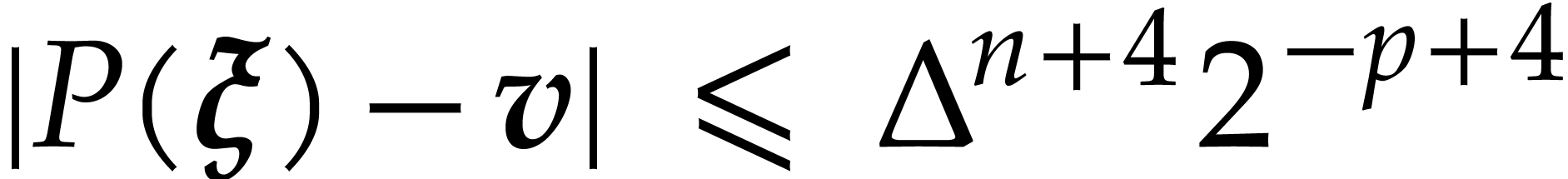

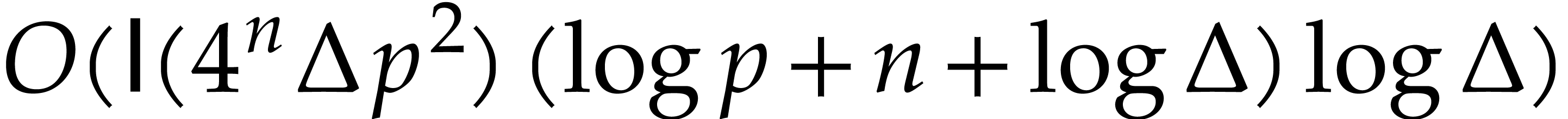

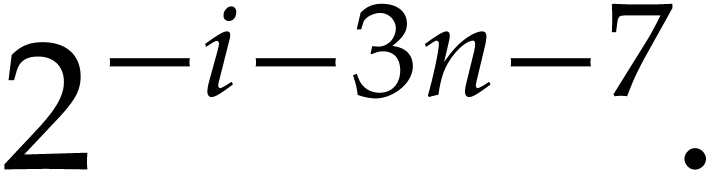

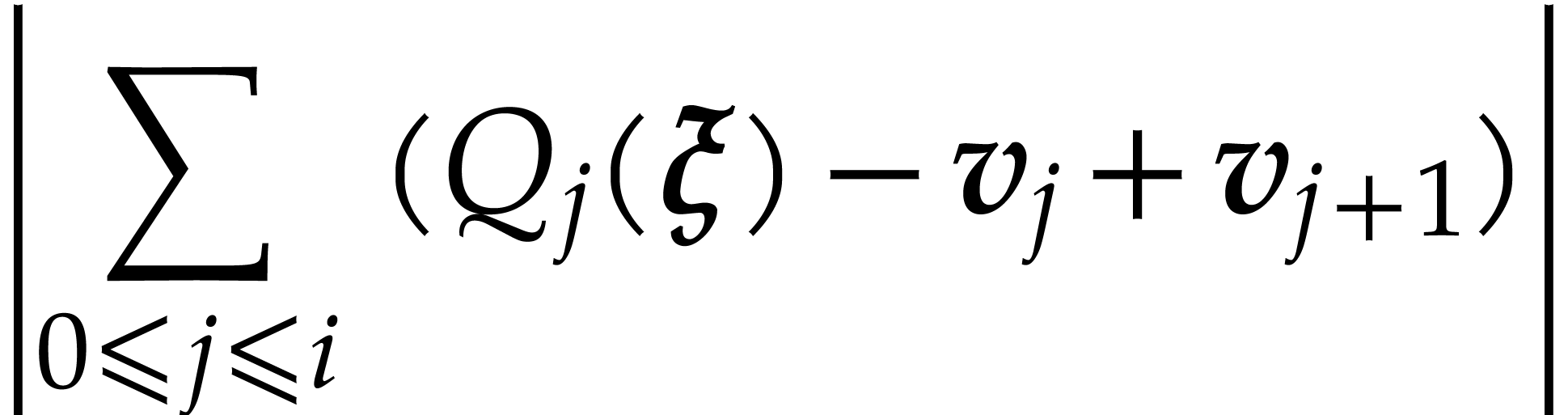

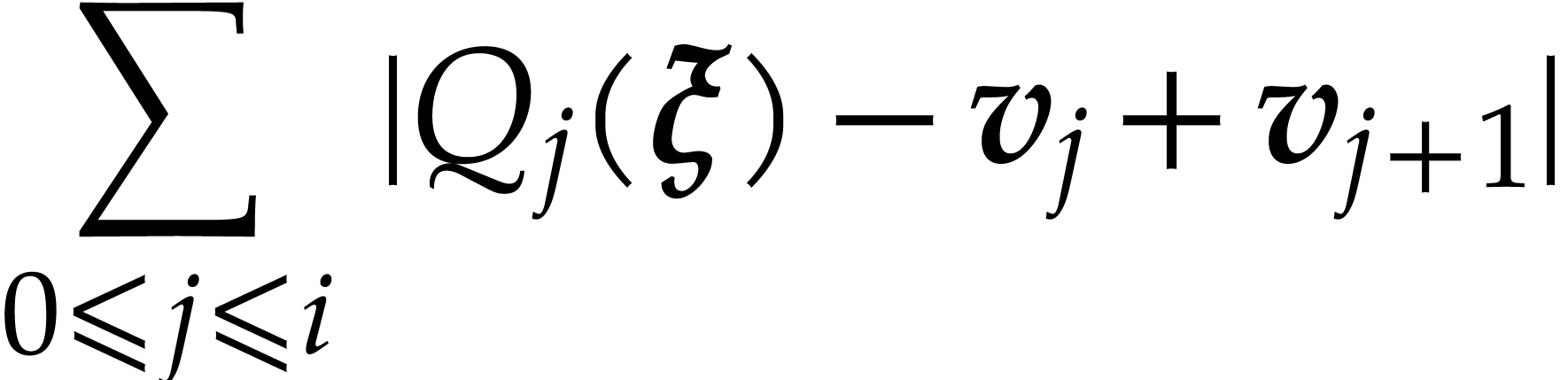

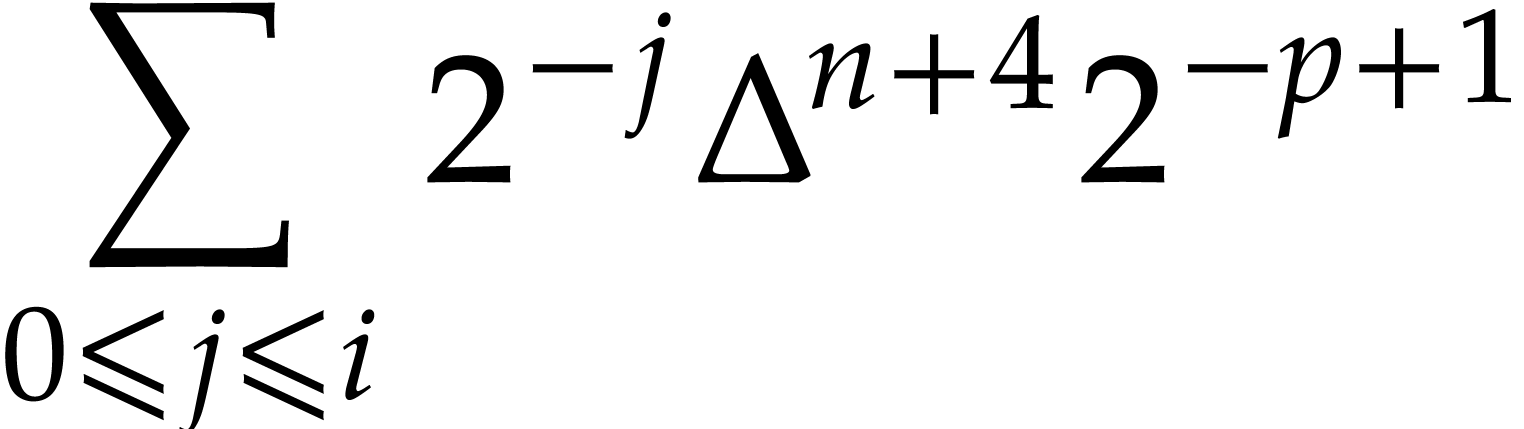

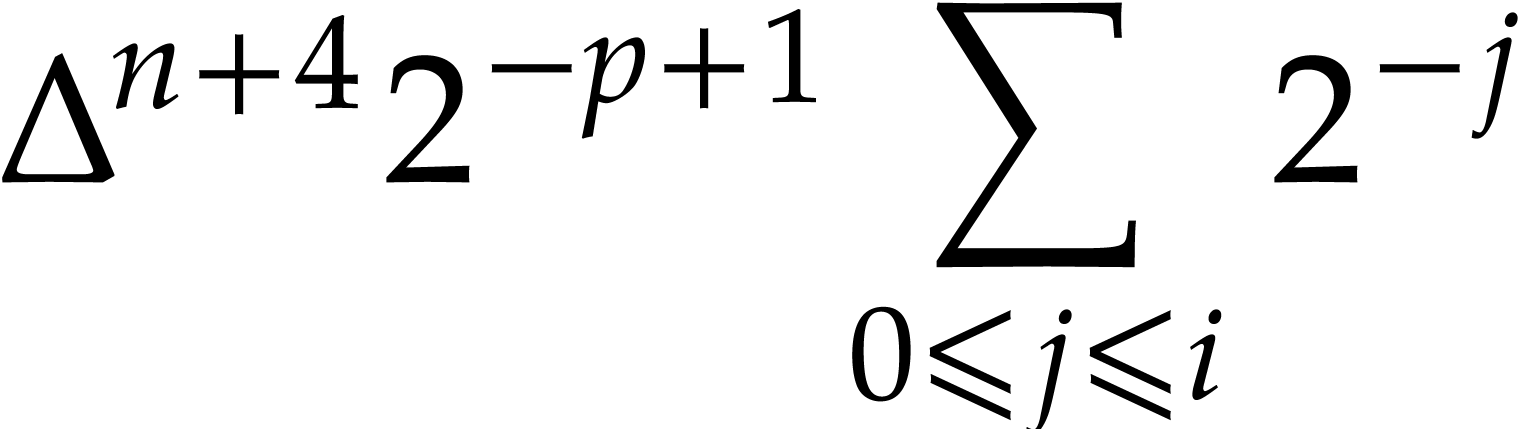

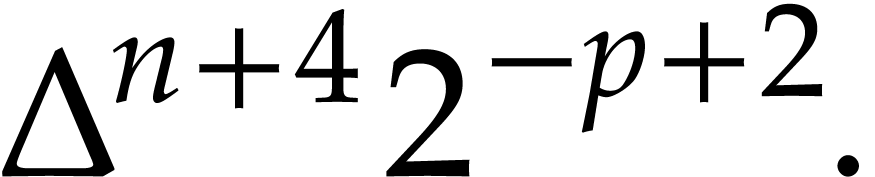

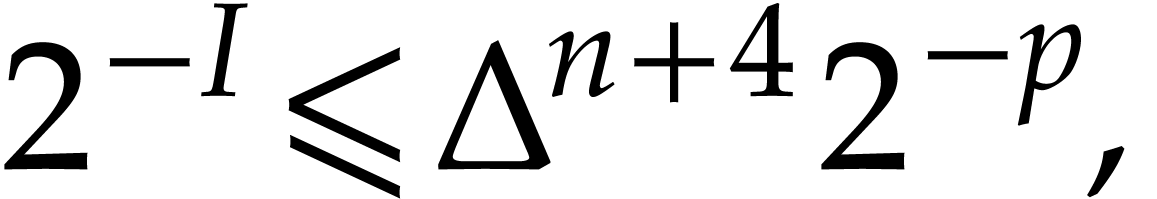

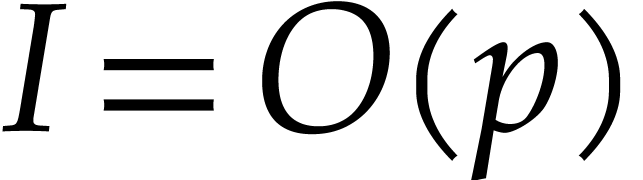

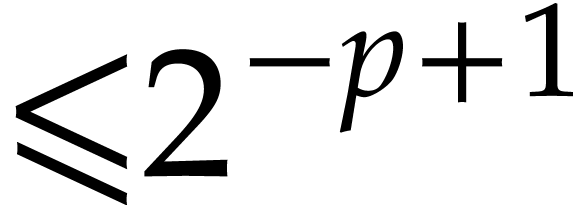

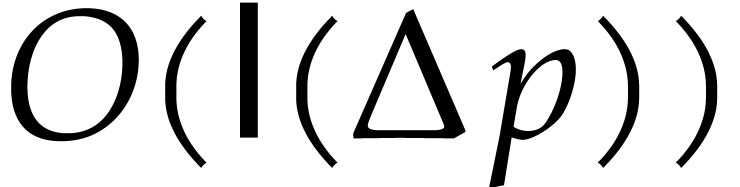

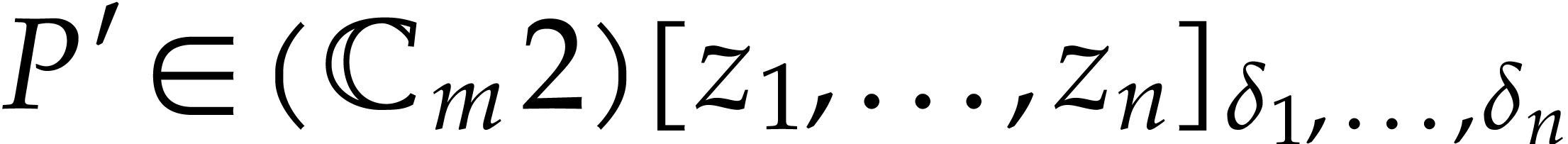

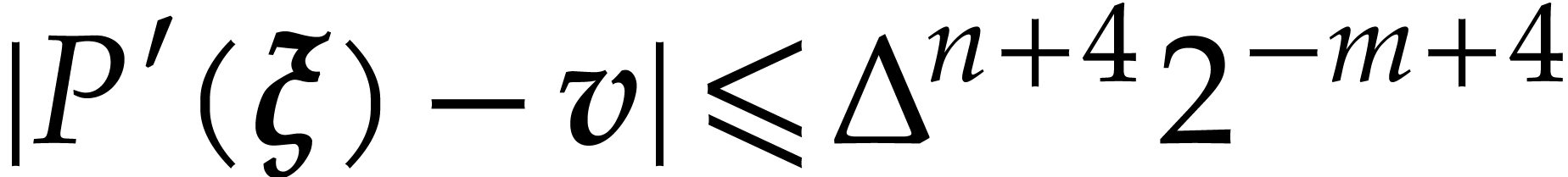

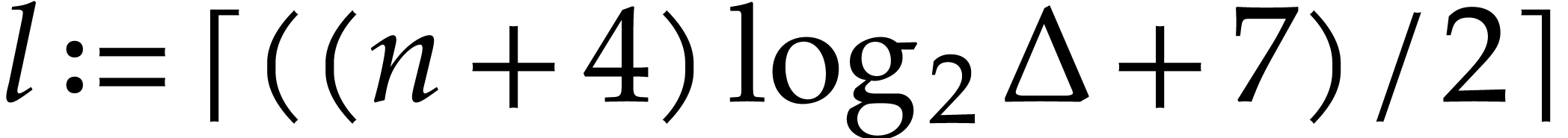

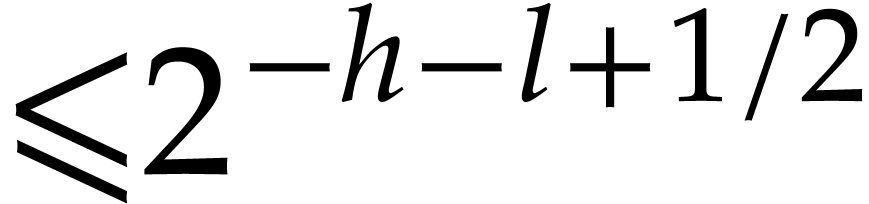

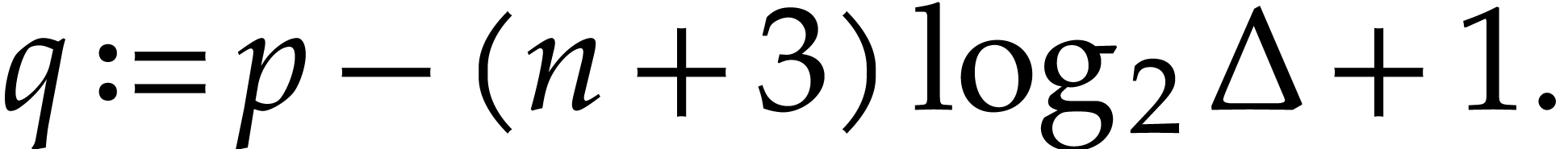

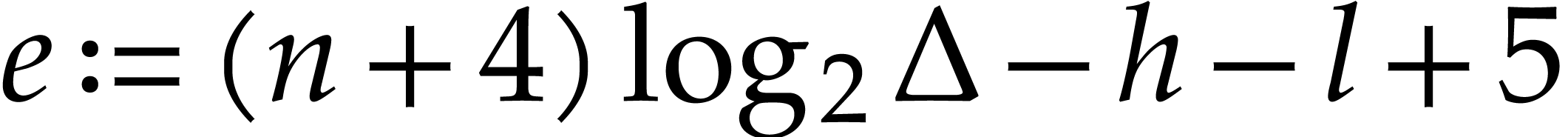

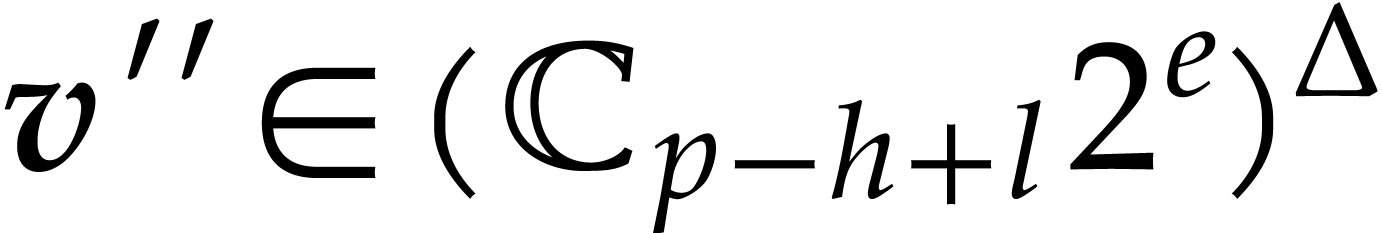

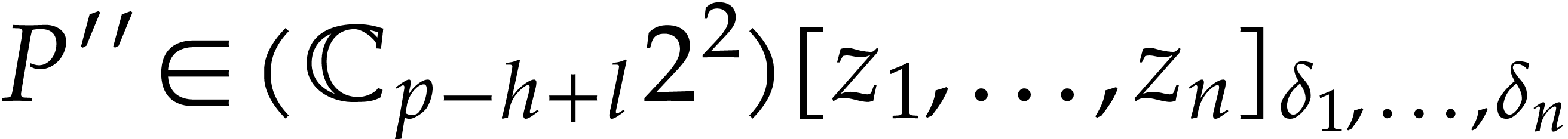

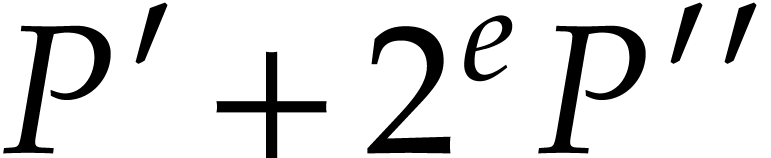

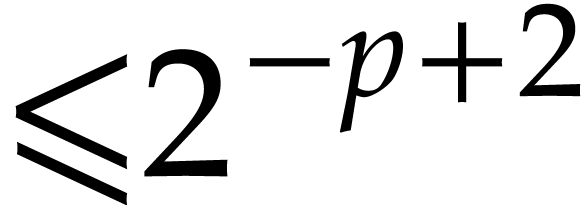

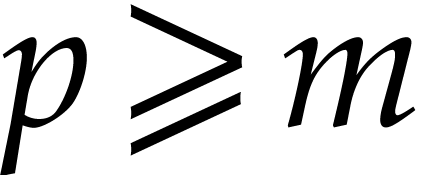

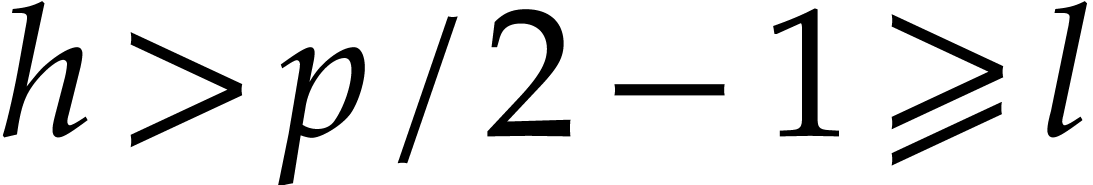

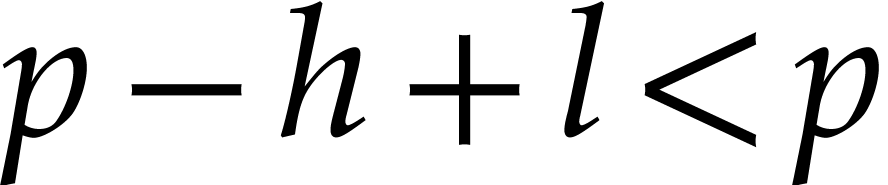

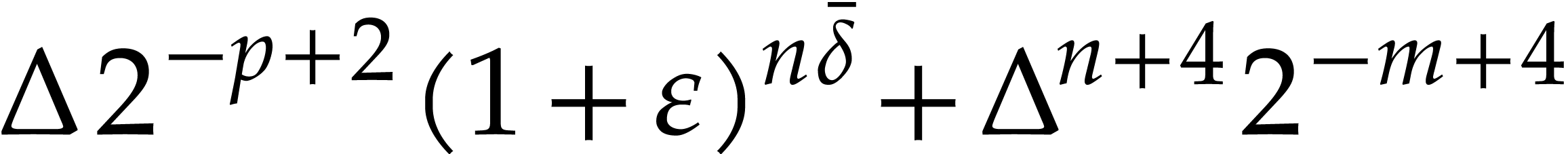

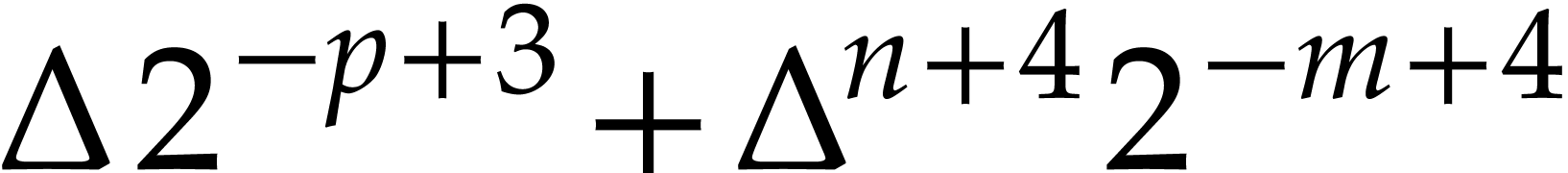

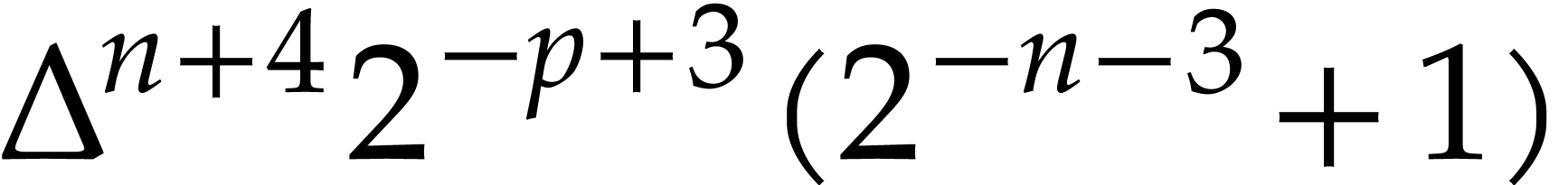

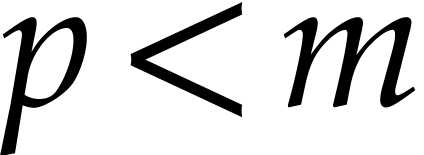

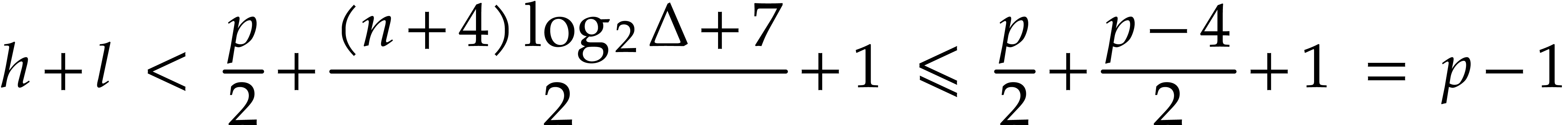

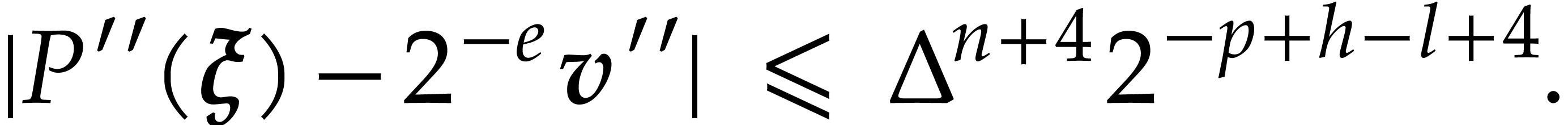

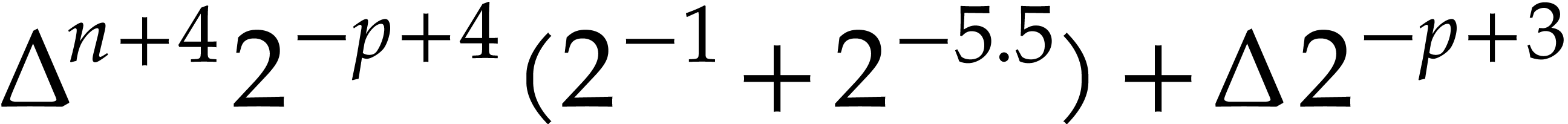

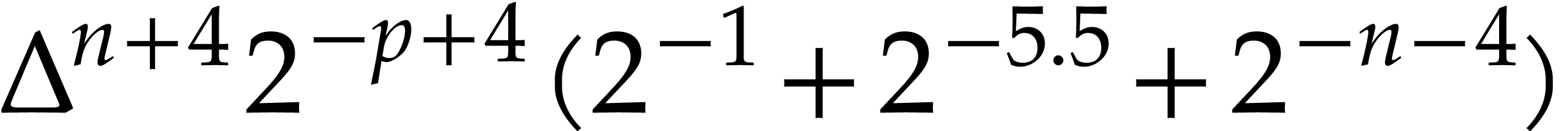

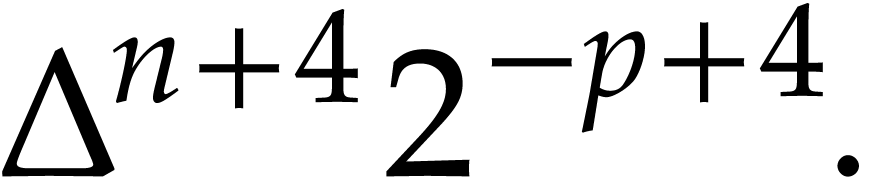

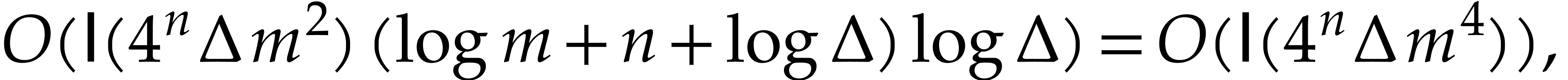

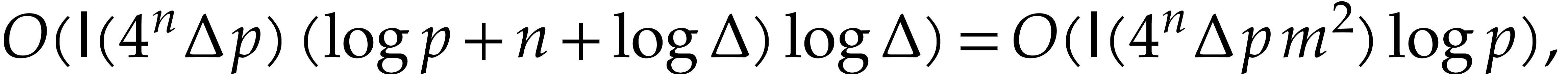

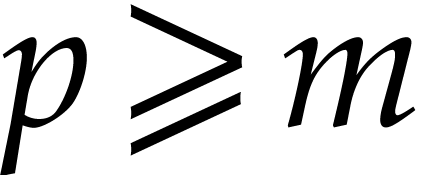

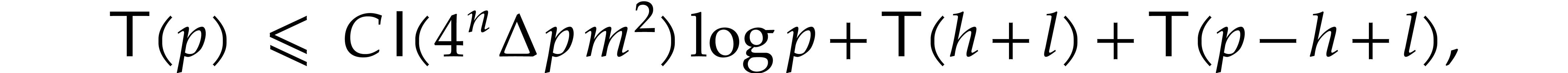

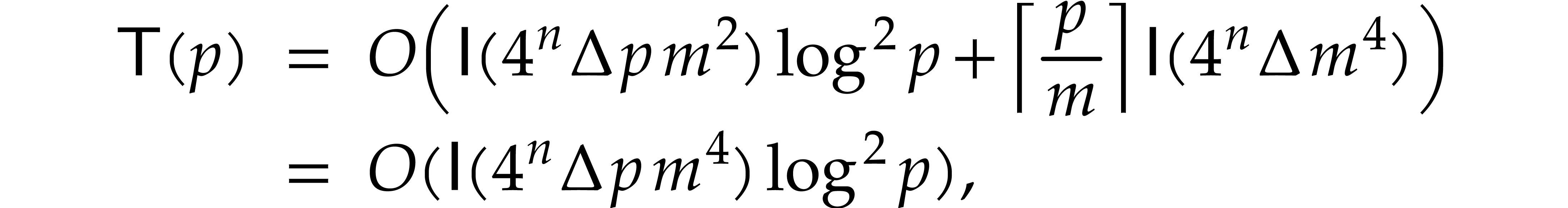

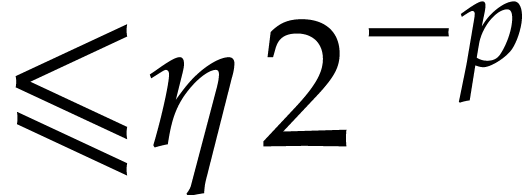

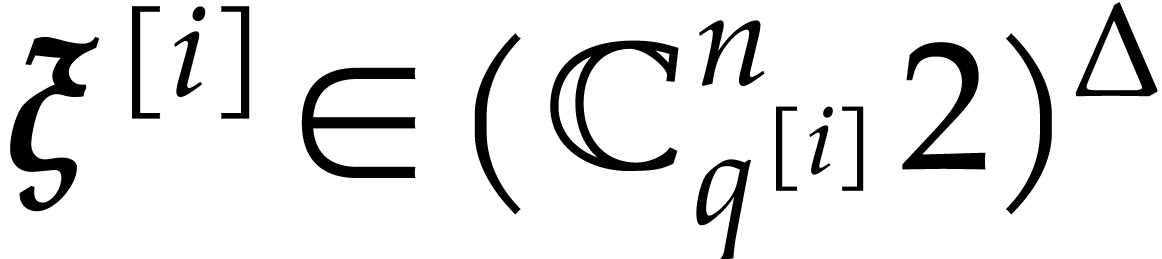

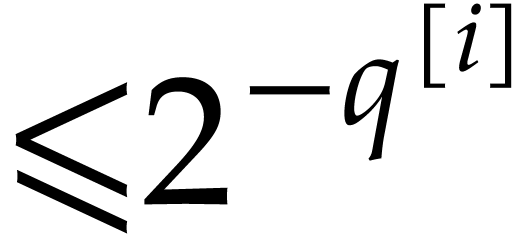

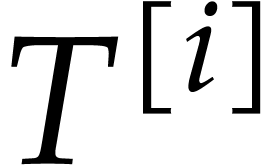

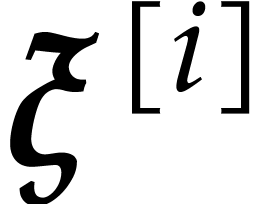

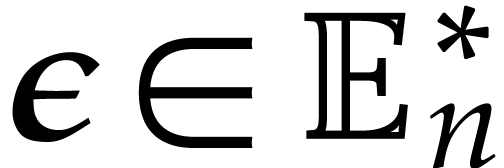

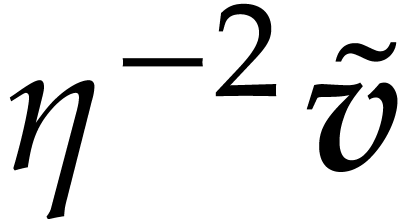

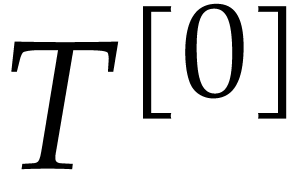

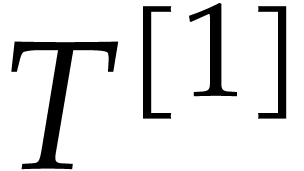

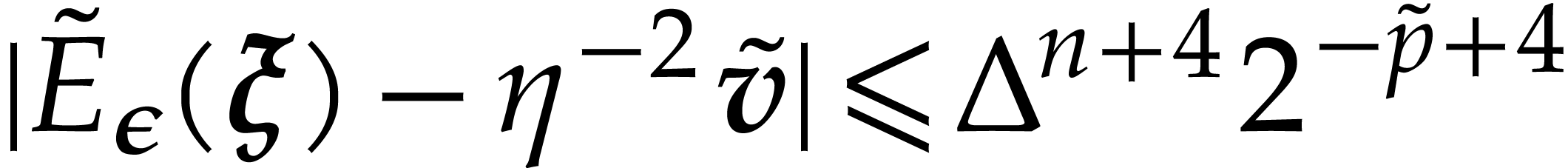

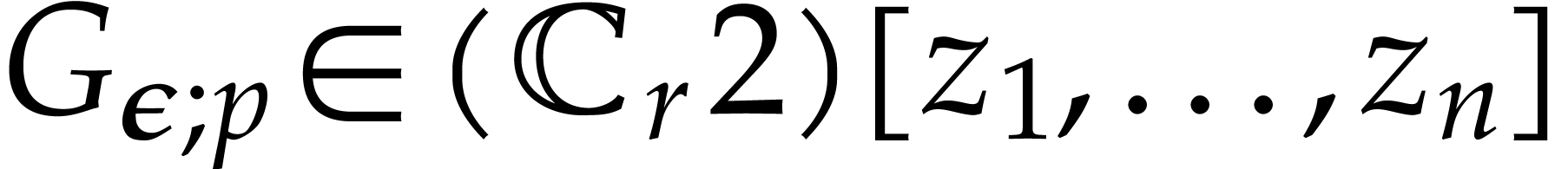

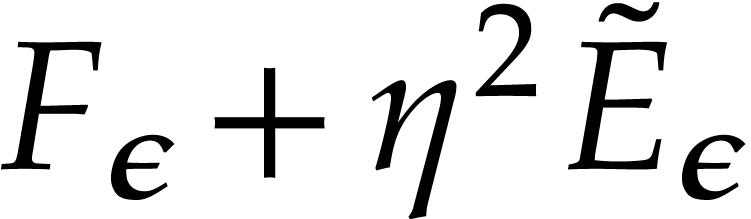

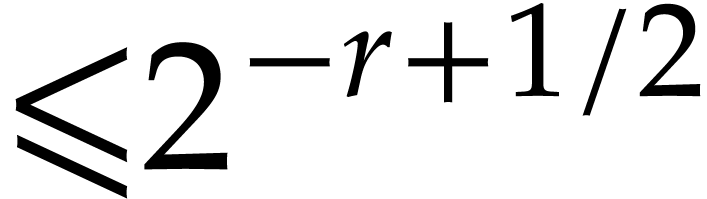

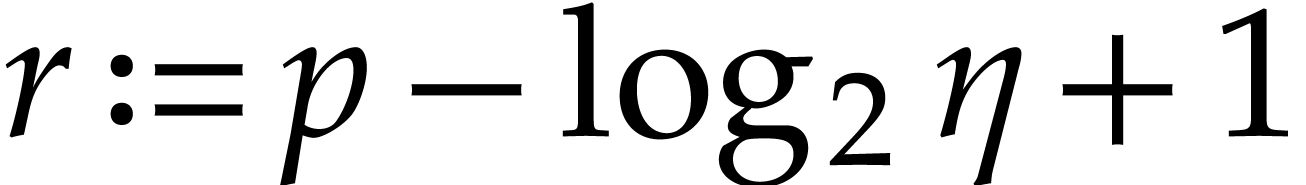

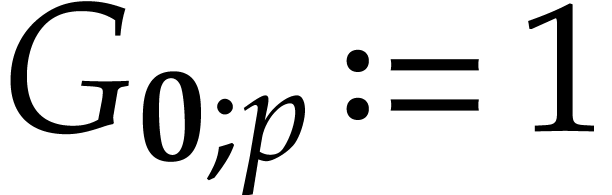

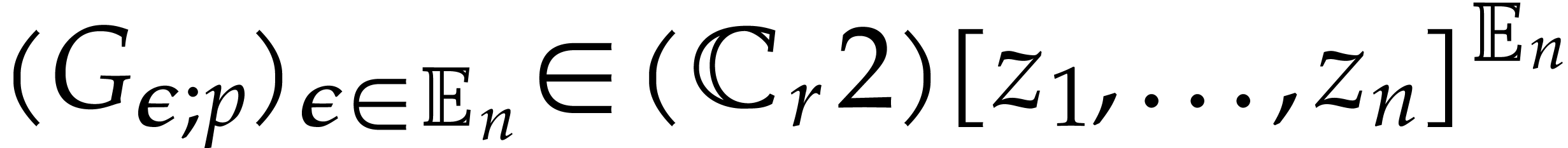

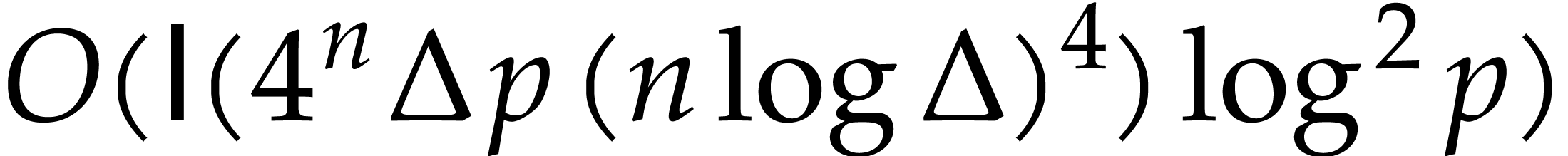

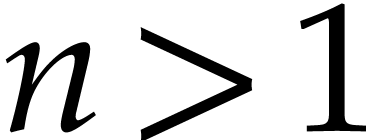

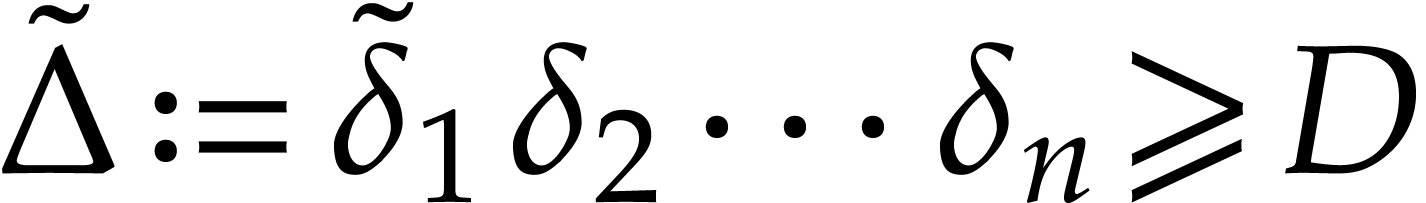

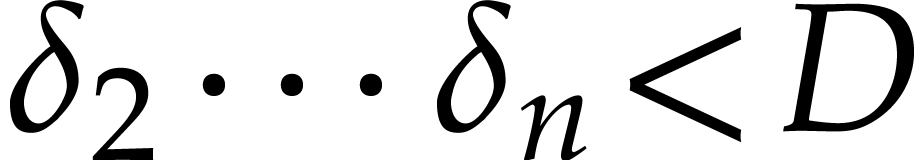

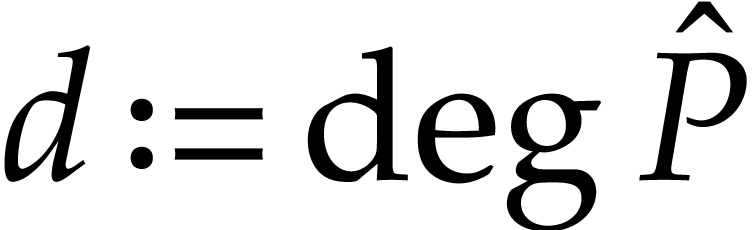

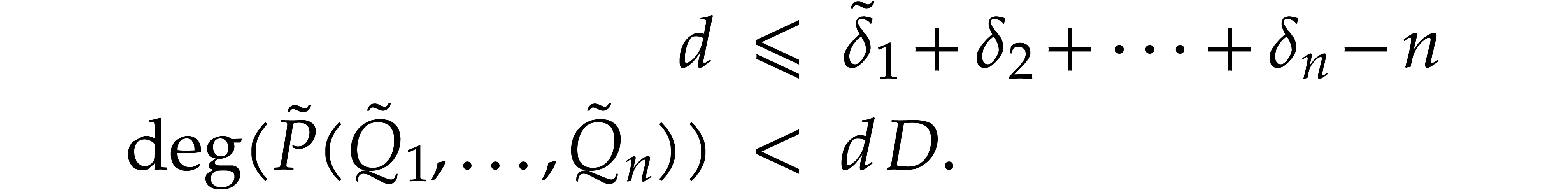

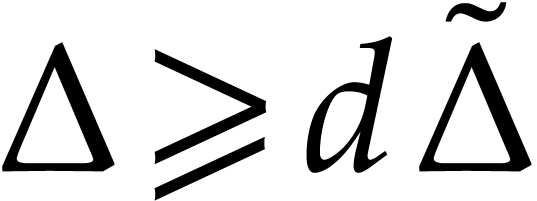

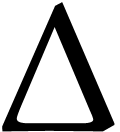

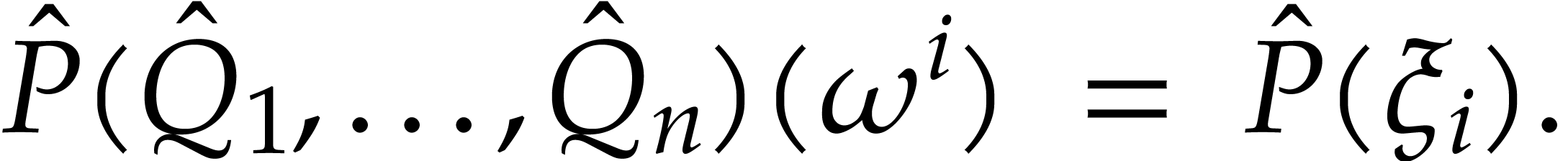

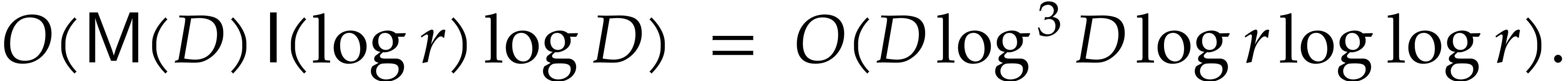

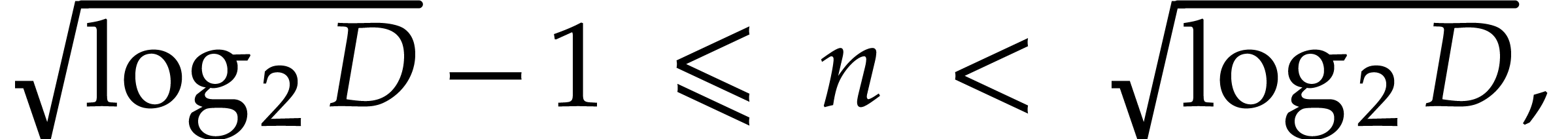

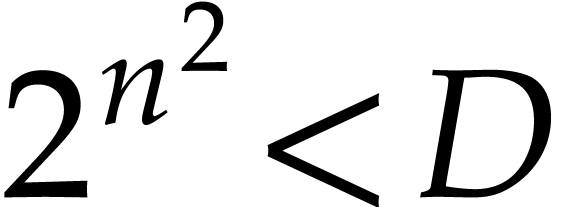

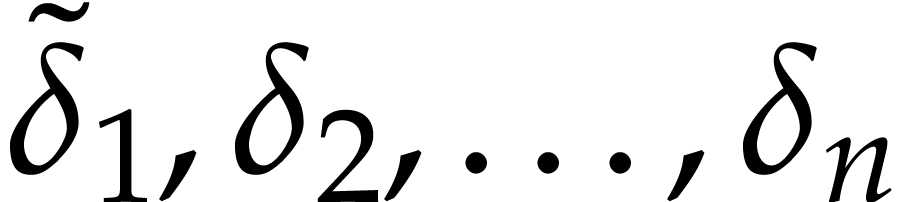

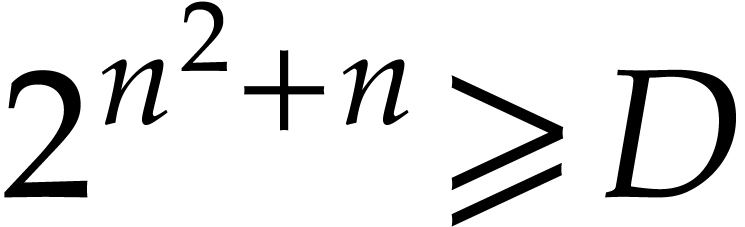

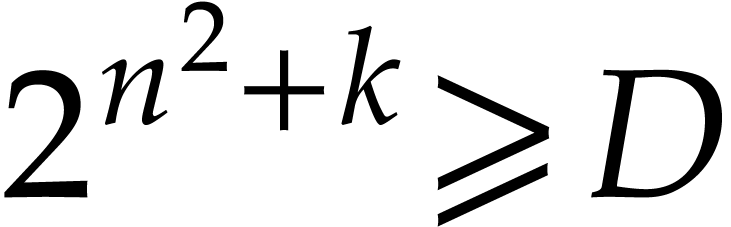

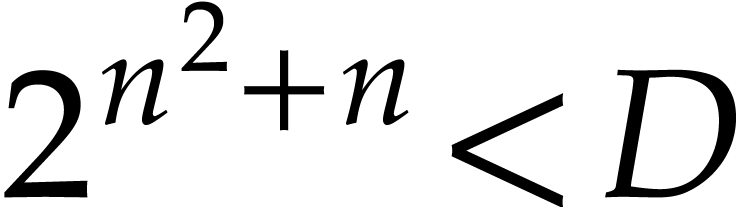

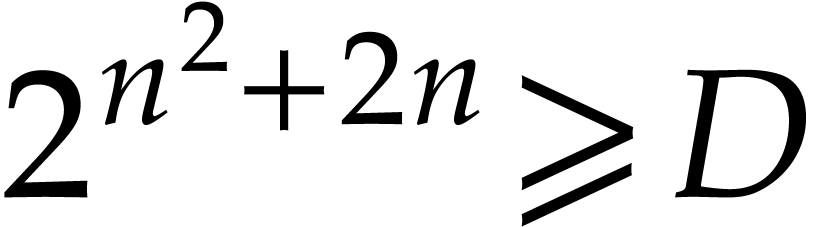

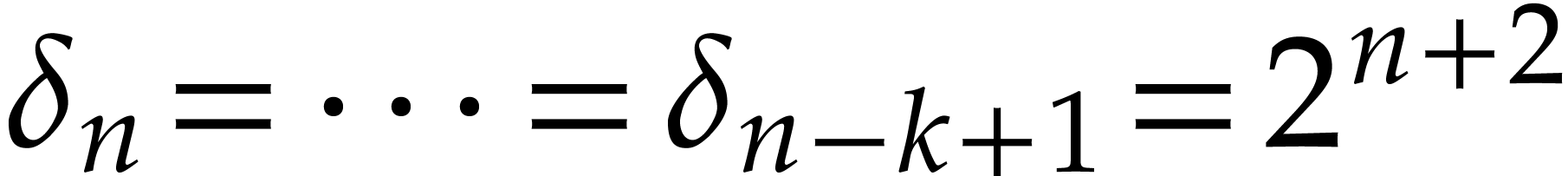

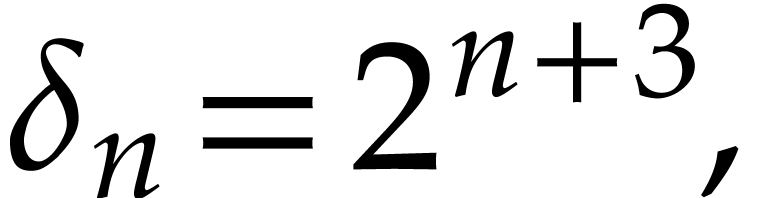

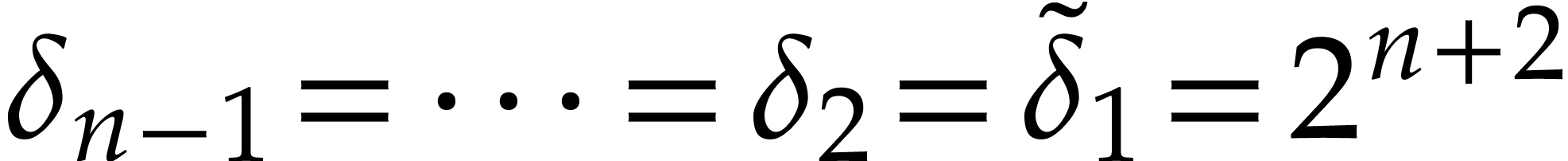

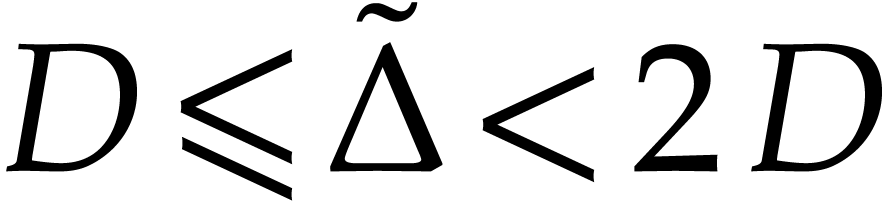

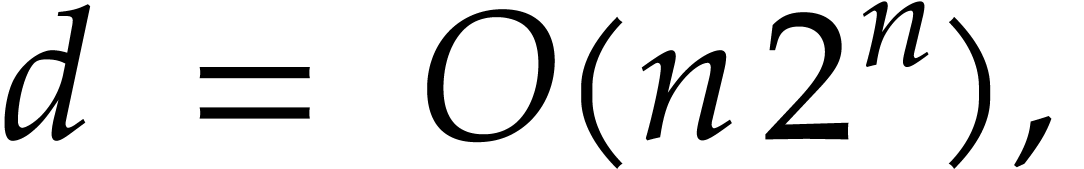

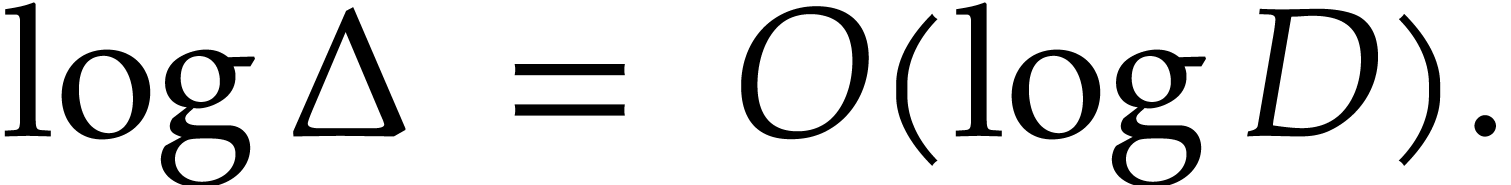

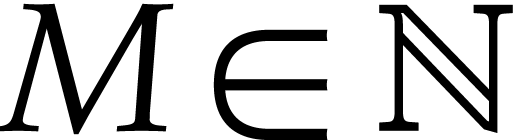

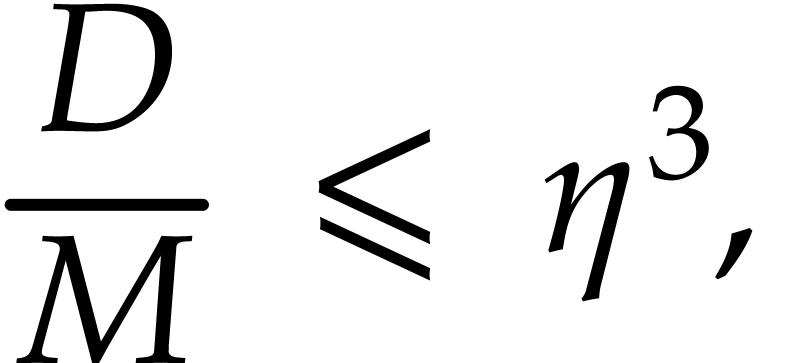

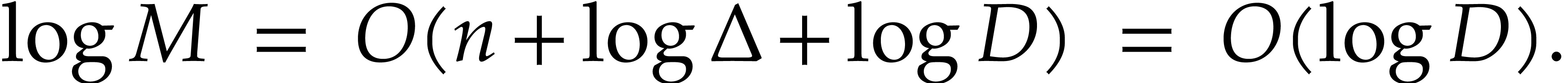

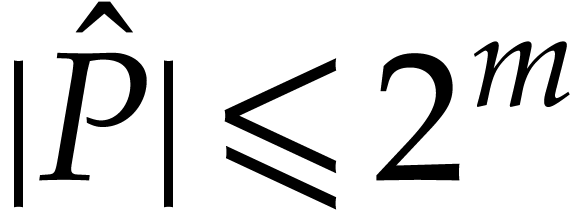

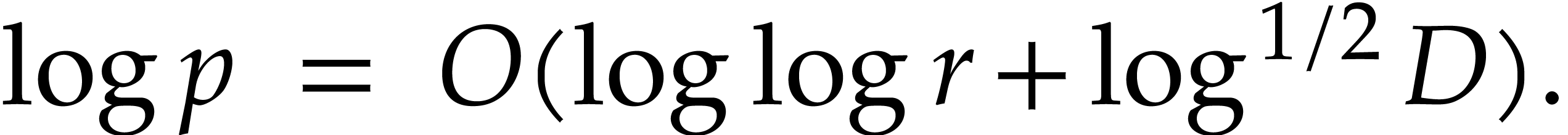

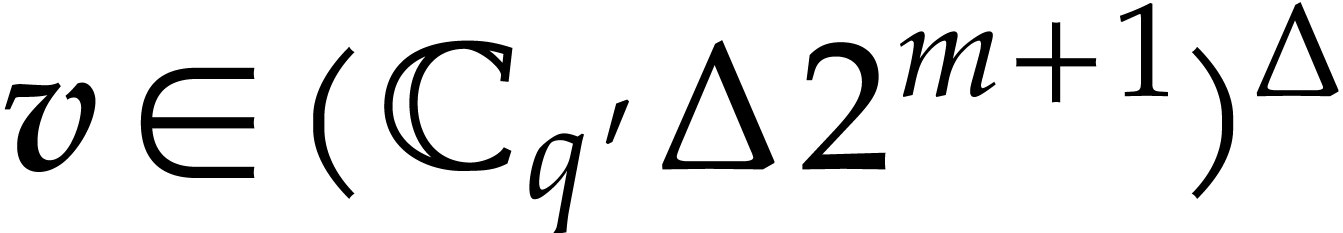

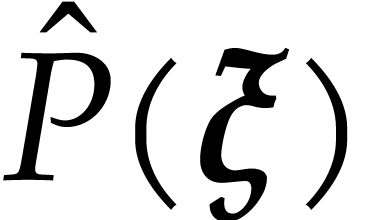

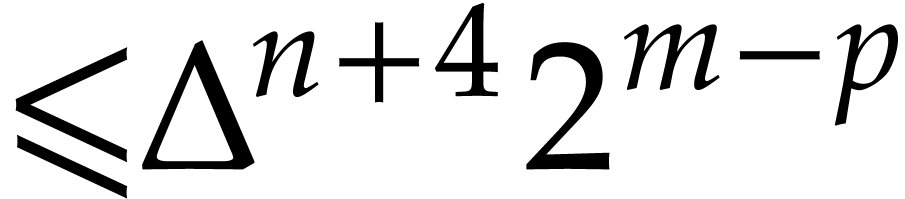

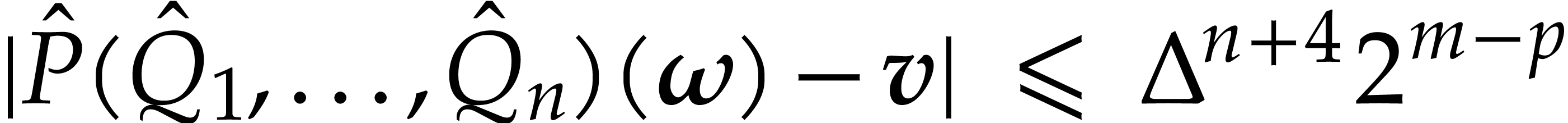

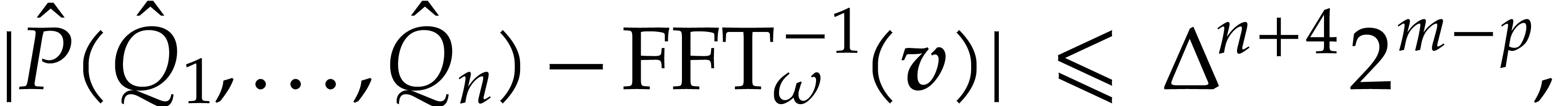

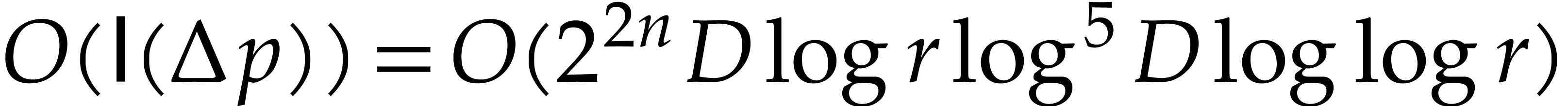

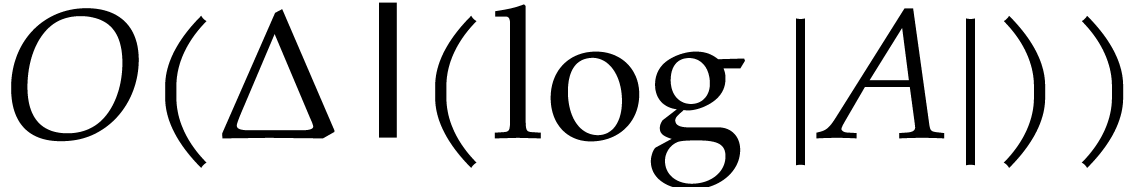

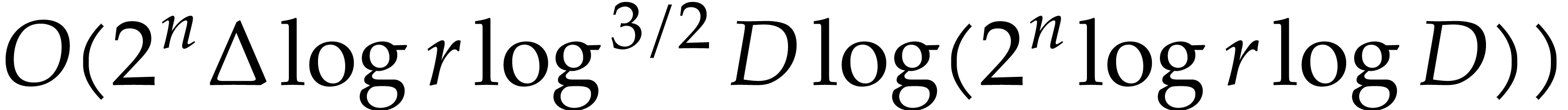

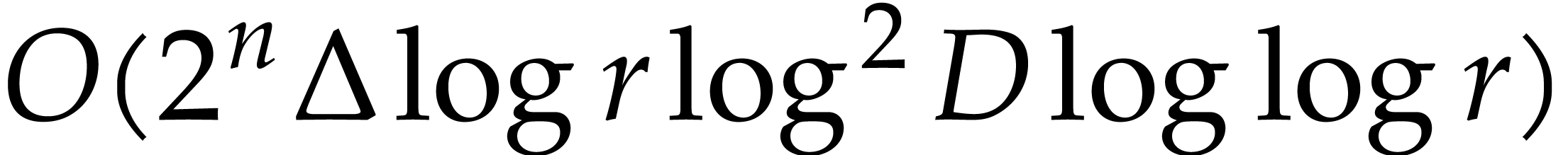

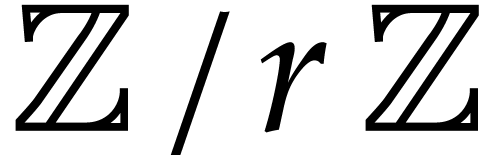

In this paper, we prove the following new complexity bound for when  is a finite ring

is a finite ring  and where

and where

is a common abbreviation for

is a common abbreviation for  .

.

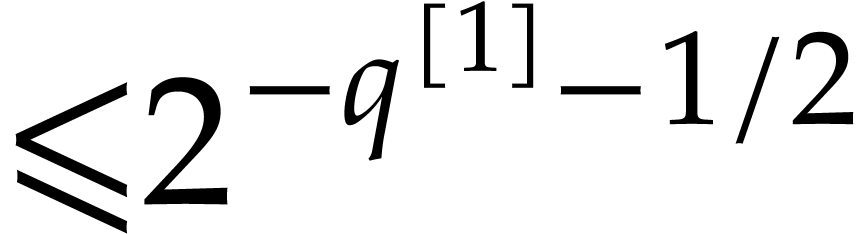

This result improves upon the best previously known bound

given in [11, Theorem 4], which is derived from an algorithm due to Kedlaya and Umans [14]. The novelty of our approach is a reduction of modular composition to the floating point evaluation of a multivariate polynomial at a special set of points, a so-called spiroid. We take advantage of fast Fourier transforms to perform these evaluations. In contrast, previously known methods, in the vein of [14], rely on number theoretic constructions.

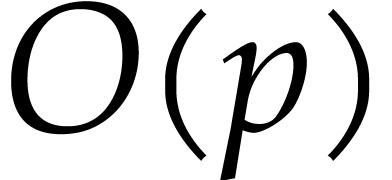

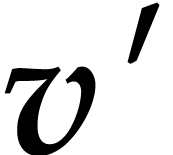

Let  denote a cost function that bounds the

number of operations in

denote a cost function that bounds the

number of operations in  required to multiply two

polynomials of degree

required to multiply two

polynomials of degree  in

in  . Over any ring

. Over any ring  ,

modular composition can be performed with

,

modular composition can be performed with  operations in

operations in  by applying Horner's rule to

evaluate

by applying Horner's rule to

evaluate  in

in  .

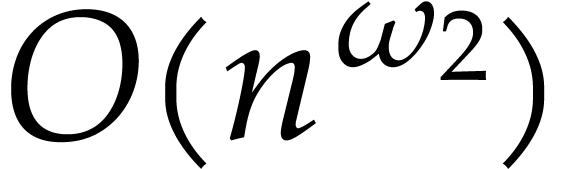

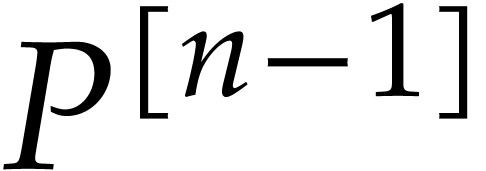

In 1978, Brent and Kung [3] gave a faster algorithm with

cost

.

In 1978, Brent and Kung [3] gave a faster algorithm with

cost  , that uses the

baby-step giant-step technique [17]. Their

algorithm even yielded a sub-quadratic cost

, that uses the

baby-step giant-step technique [17]. Their

algorithm even yielded a sub-quadratic cost  when

combined with fast linear algebra; see [13, p. 185]. Here,

the constant

when

combined with fast linear algebra; see [13, p. 185]. Here,

the constant  is a real value between 3 and 4

such that the product of a

is a real value between 3 and 4

such that the product of a  matrix by a

matrix by a  matrix takes

matrix takes  operations; one may

take

operations; one may

take  according to [19]. At present

time, the fastest known modular composition method over any ground field

according to [19]. At present

time, the fastest known modular composition method over any ground field

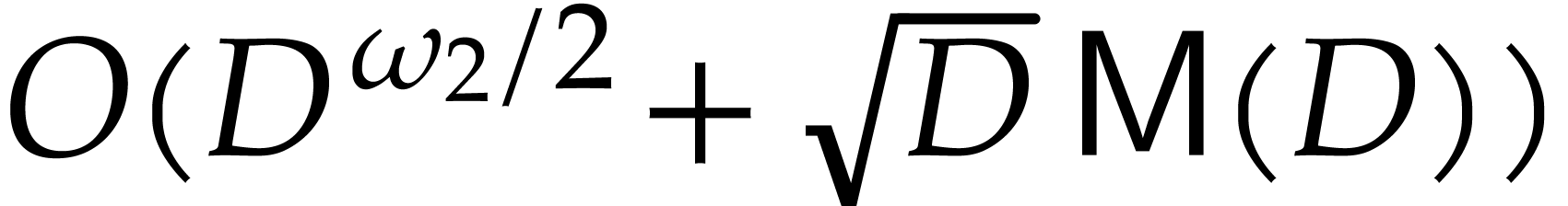

is due to Neiger, Salvy, Schost, and Villard [16]: it is probabilistic of Las Vegas type and takes an

expected number of

is due to Neiger, Salvy, Schost, and Villard [16]: it is probabilistic of Las Vegas type and takes an

expected number of

operations in  ; see [16,

Theorem 1.1]. Here, the constant

; see [16,

Theorem 1.1]. Here, the constant  denotes any

real value between

denotes any

real value between  and

and  such that two

such that two  matrices over a commutative ring

can be multiplied with

matrices over a commutative ring

can be multiplied with  ring operations. The

current best known value is

ring operations. The

current best known value is  [19],

so we may take

[19],

so we may take  .

.

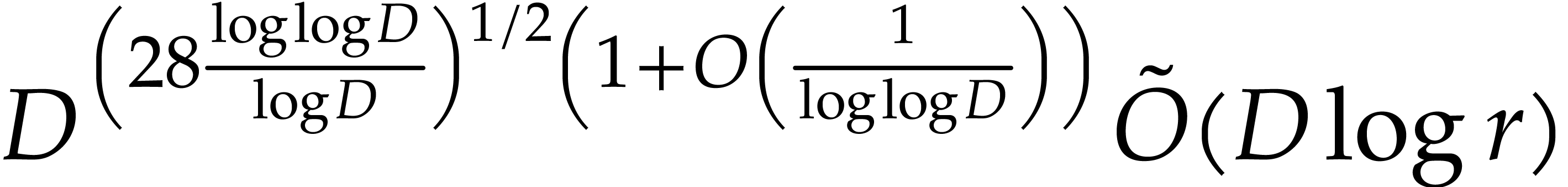

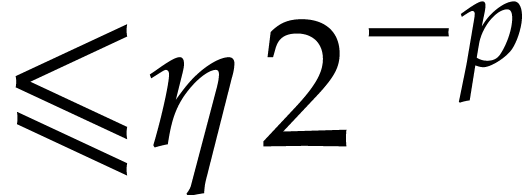

A major breakthrough for the modular composition problem is due to

Kedlaya and Umans [14] in the case where  is a finite field

is a finite field  (and even more generally a

finite ring of the form

(and even more generally a

finite ring of the form  for any integer

for any integer  and

and  monic). For any fixed

real value

monic). For any fixed

real value  , they showed that

, they showed that

can be computed using

can be computed using  bit operations. The dependency in

bit operations. The dependency in  is analyzed in

[11]. Recent improvements of the Kedlaya–Umans

approach can be found in [1, 2], but the

dependency in

is analyzed in

[11]. Recent improvements of the Kedlaya–Umans

approach can be found in [1, 2], but the

dependency in  is not detailed.

is not detailed.

In [9, 10] it was shown how the knowledge of

factorizations of  can be exploited to speed up

modular composition. An important special case concerns the composition

of power series, which corresponds to taking

can be exploited to speed up

modular composition. An important special case concerns the composition

of power series, which corresponds to taking  . Recently, Kinoshita and Li [15]

showed how to accomplish this task using

. Recently, Kinoshita and Li [15]

showed how to accomplish this task using  operations in

operations in  .

.

Our modular composition algorithm will be presented in section 5: Theorem 1 follows from the sharper complexity bound given in Theorem 24. As in [14], the problem will be reduced to the multi-point evaluation of a multivariate polynomial, using Kronecker segmentation. But, instead of relying on finite field arithmetic, we benefit from floating point arithmetic and reduce the multi-point evaluation to a deformation of the fast Fourier transform. The deformed evaluation point set is presented in section 3. Corresponding evaluation and interpolation algorithms are given in section 4. The next section gathers prerequisites.

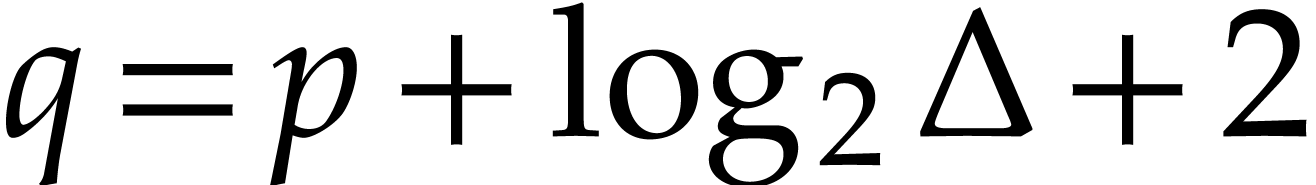

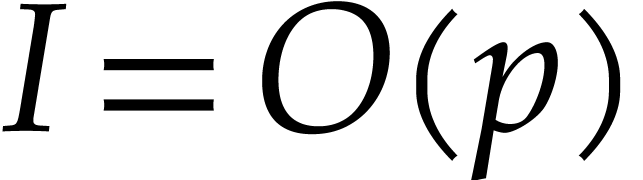

For complexity analyses, we will consider bit complexity models such as

computation trees or RAM machines [4, 5]. The

function  will bound the bit cost for multiplying

two integers of bit size

will bound the bit cost for multiplying

two integers of bit size  . We

will assume that

. We

will assume that  is nondecreasing. At the end,

we will make use of the fast product of [6], that yields

is nondecreasing. At the end,

we will make use of the fast product of [6], that yields

.

.

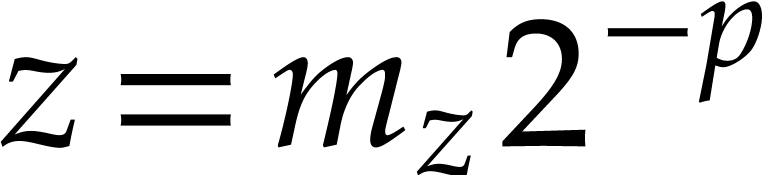

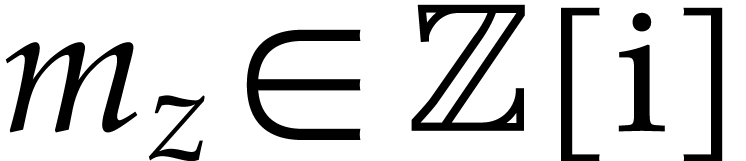

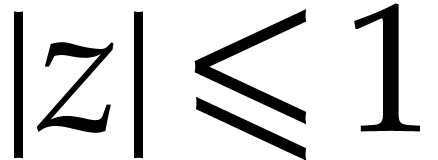

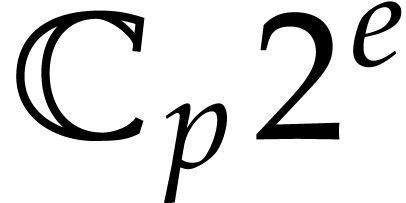

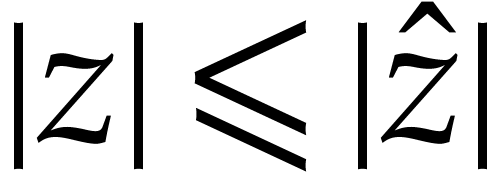

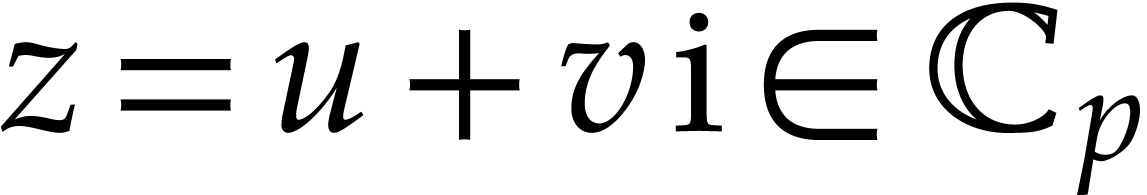

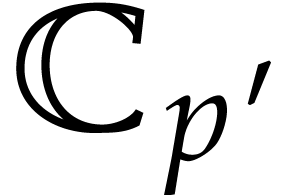

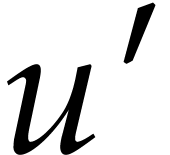

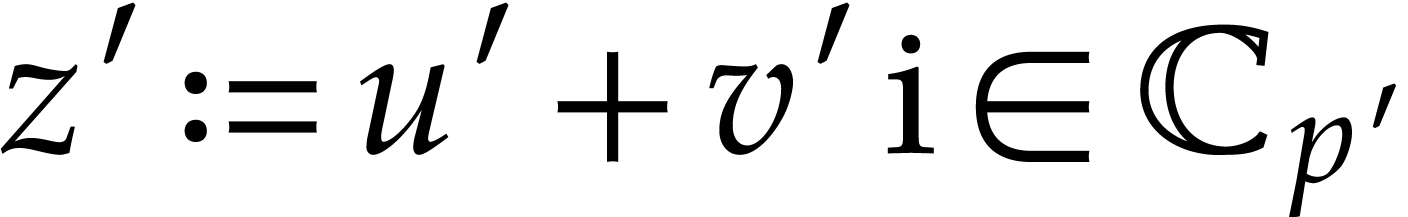

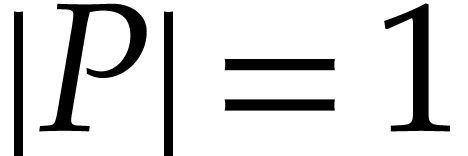

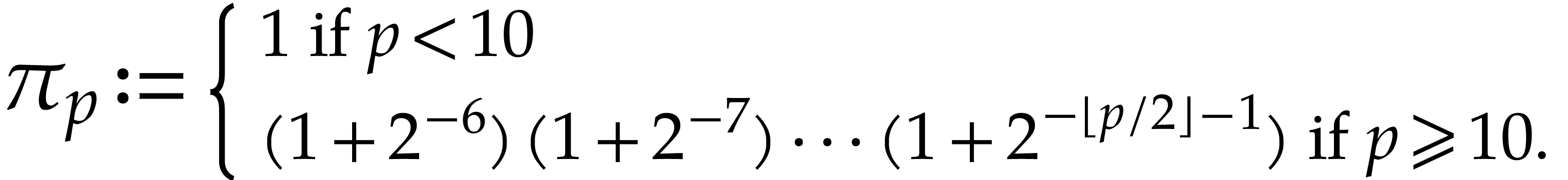

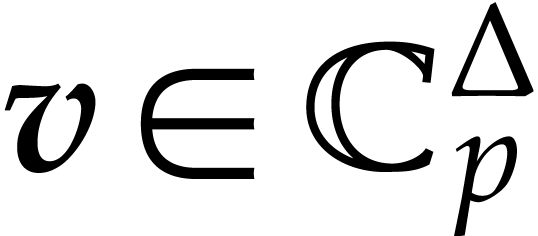

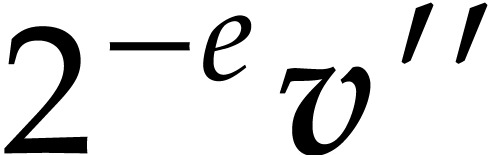

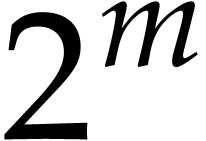

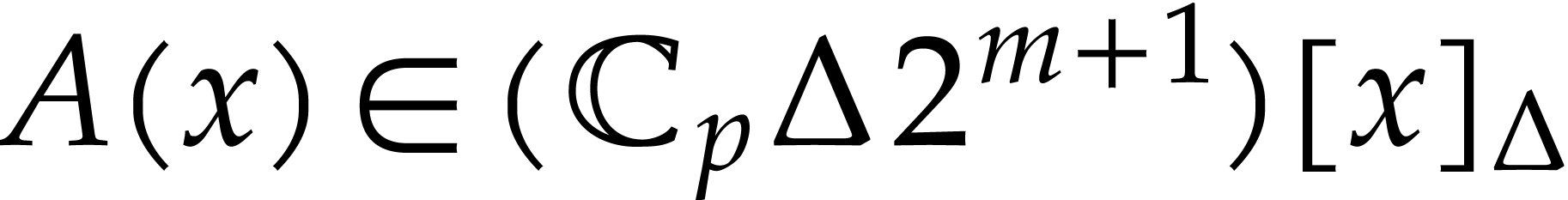

Numbers will be represented in radix  ,

with a finite number of digits. We will represent fixed point numbers by

a signed mantissa and a fixed exponent. More precisely, given a

precision parameter

,

with a finite number of digits. We will represent fixed point numbers by

a signed mantissa and a fixed exponent. More precisely, given a

precision parameter  , we

denote by

, we

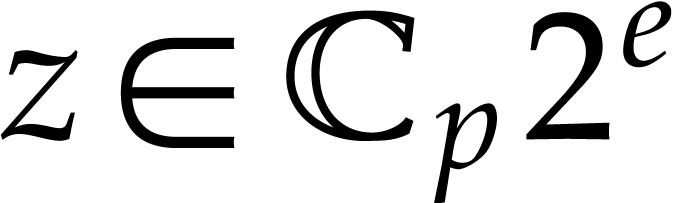

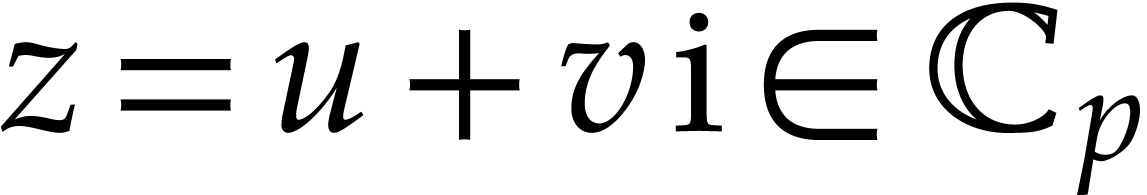

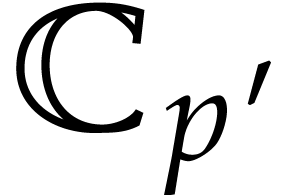

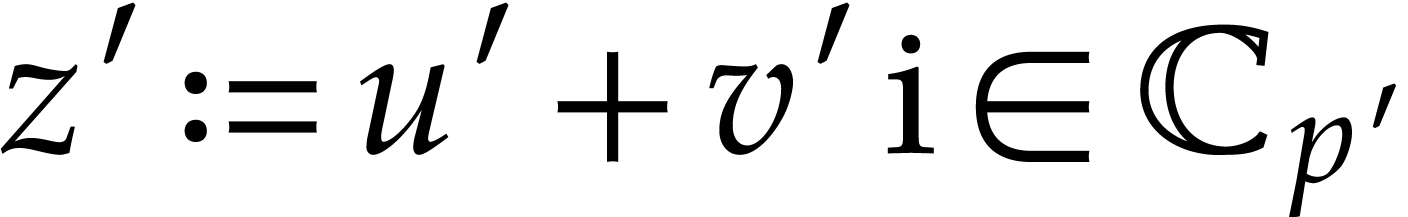

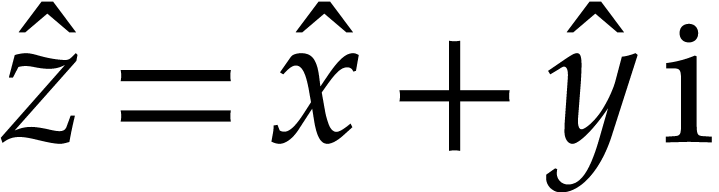

denote by  the set of complex numbers of the form

the set of complex numbers of the form

, where

, where  and

and  . We write

. We write  for the set of complex numbers of the form

for the set of complex numbers of the form  , where

, where  and

and  ; in particular, for

; in particular, for  we always have

we always have  .

At every stage of our algorithms, the exponent

.

At every stage of our algorithms, the exponent  will be specified, so the exponents do not have to be stored or

manipulated explicitly.

will be specified, so the exponents do not have to be stored or

manipulated explicitly.

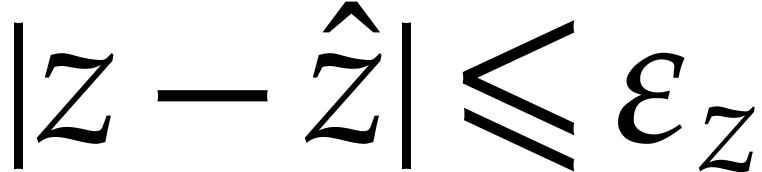

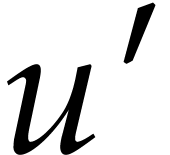

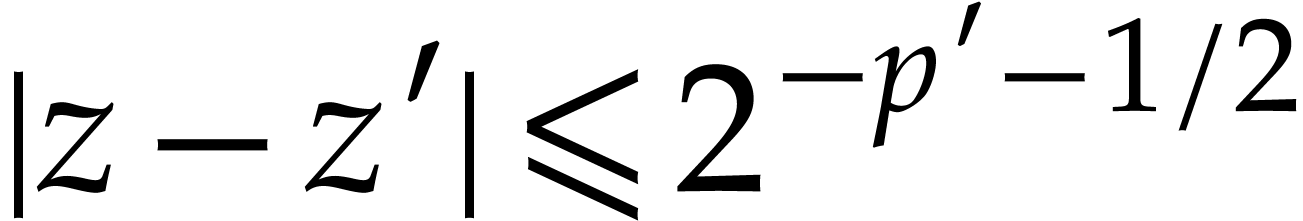

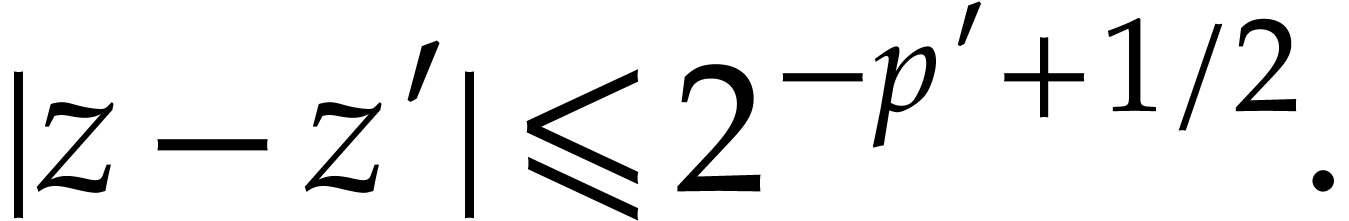

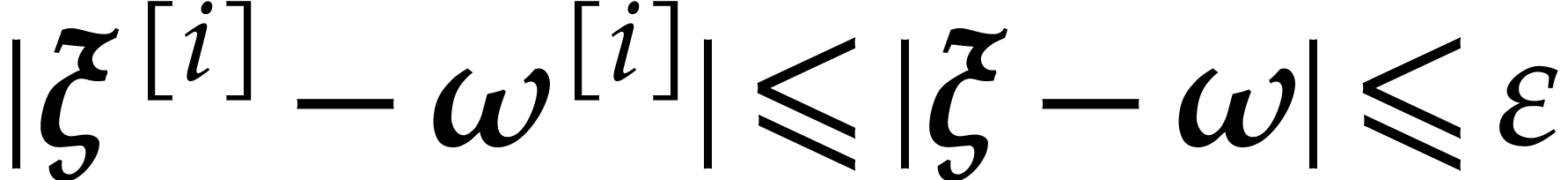

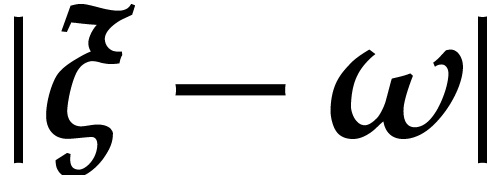

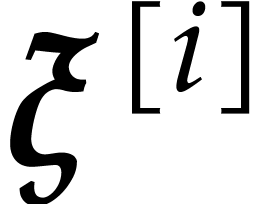

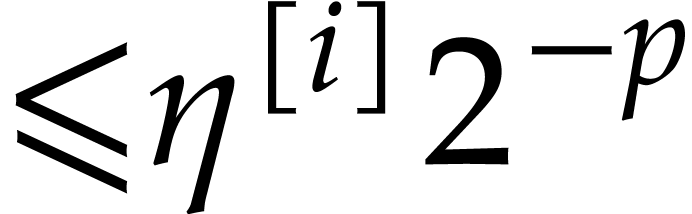

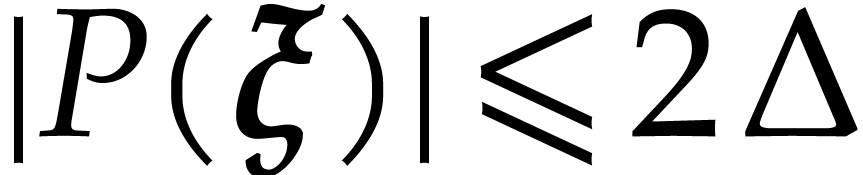

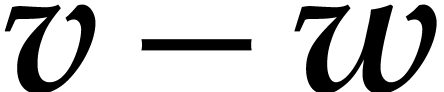

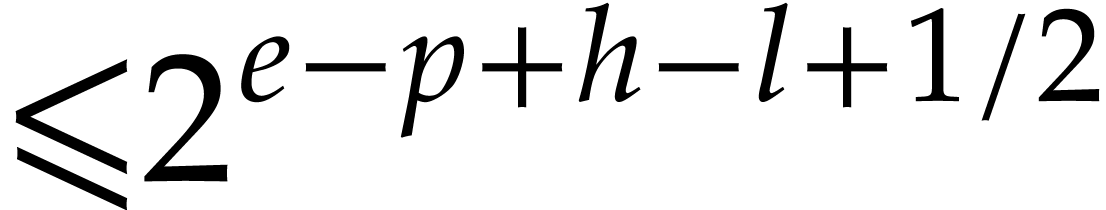

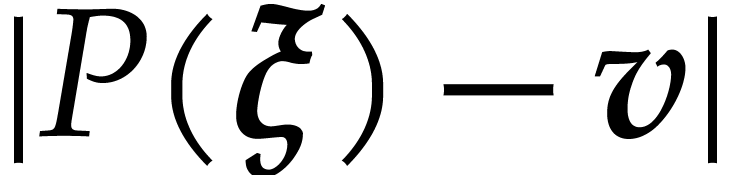

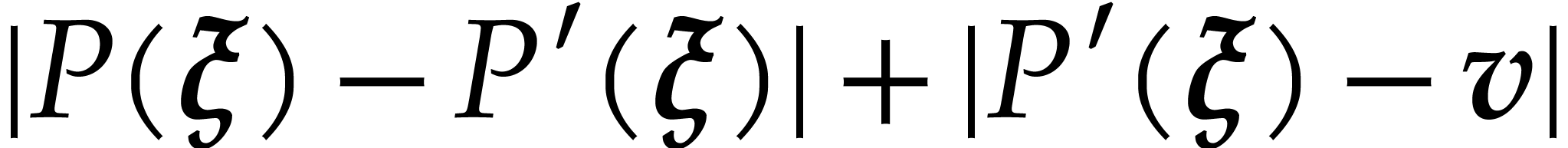

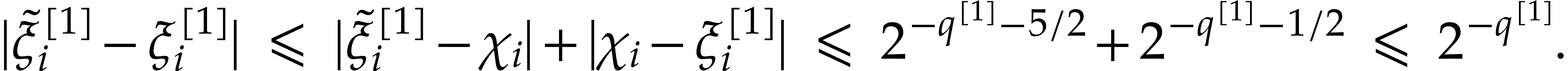

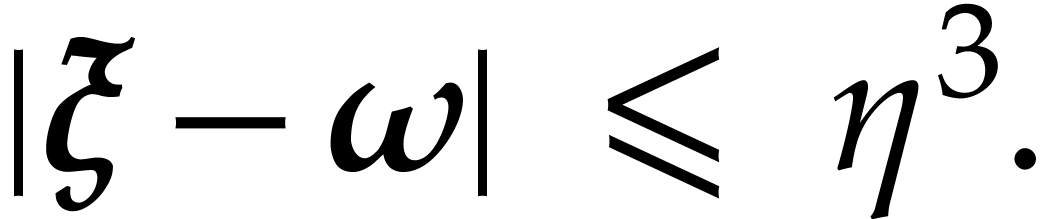

In the error analyses of our numerical algorithms, each  is really the approximation of some genuine complex number

is really the approximation of some genuine complex number  . So each such

. So each such  comes

with an implicit error bound

comes

with an implicit error bound  ;

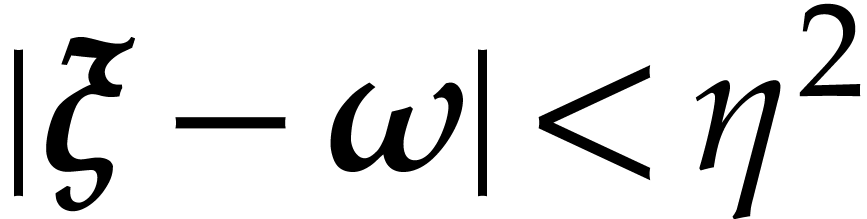

this is a real number for which we can guarantee that

;

this is a real number for which we can guarantee that  . A truncation of

. A truncation of  is an approximation

is an approximation  of

of  that is rounded towards zero in the sense that

that is rounded towards zero in the sense that  . Given

. Given  ,

the sum

,

the sum  can be computed exactly in time

can be computed exactly in time  . The product

. The product  can be computed exactly in time

can be computed exactly in time  .

.

Proof. Rounding  into

into

can be done as follows: let

can be done as follows: let  and

and  be the truncations to the nearest of

be the truncations to the nearest of  and

and  into

into  and let

and let  ; Then we have

; Then we have  .

.

Proof. Rounding  towards

zero into

towards

zero into  can be done as follows: let

can be done as follows: let  and

and  be the truncations of

be the truncations of  and

and  at precision

at precision  and let

and let  ; Then

we have

; Then

we have  and

and

Let  be a power of

be a power of  and

let

and

let  be a vector of complex numbers. We write

be a vector of complex numbers. We write

and

and  .

.

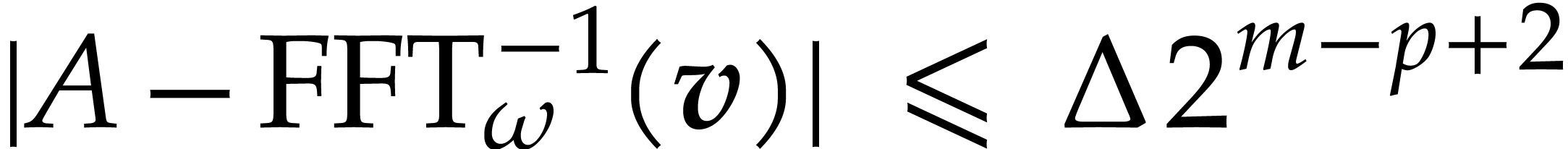

Proof. We use [7, Proposition 4] at

precision  in order to obtain first

approximations of

in order to obtain first

approximations of  in

in  with error

with error  . We next truncate

these results in

. We next truncate

these results in  , which

yields an overall error

, which

yields an overall error  thanks to Lemma 3.

thanks to Lemma 3.

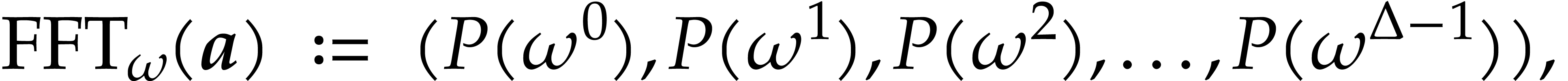

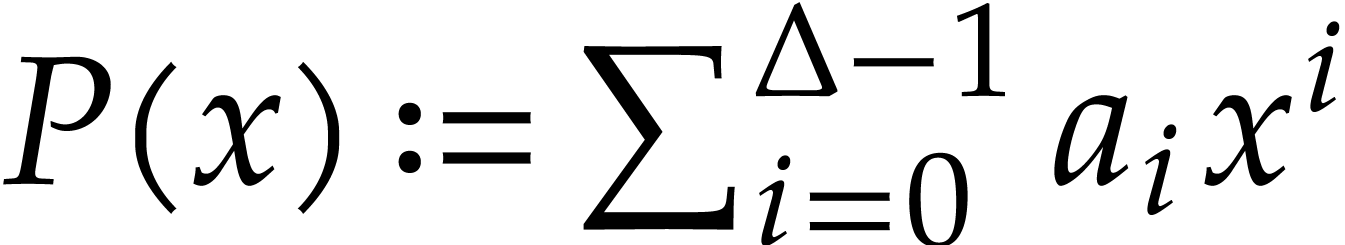

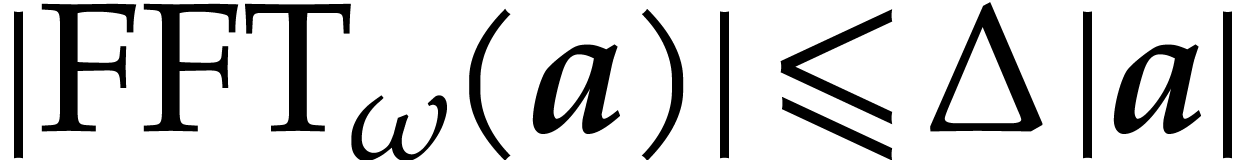

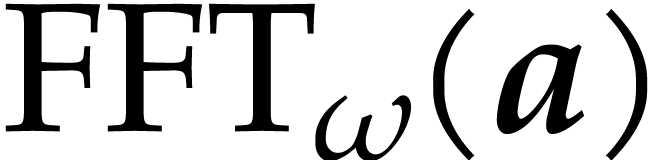

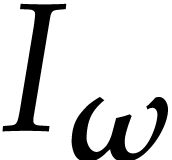

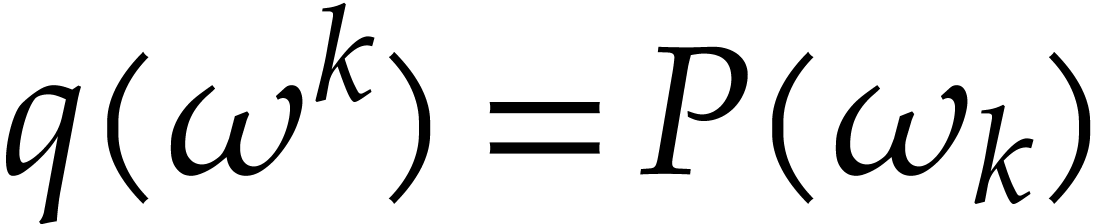

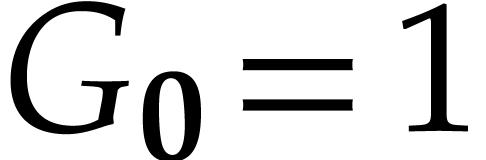

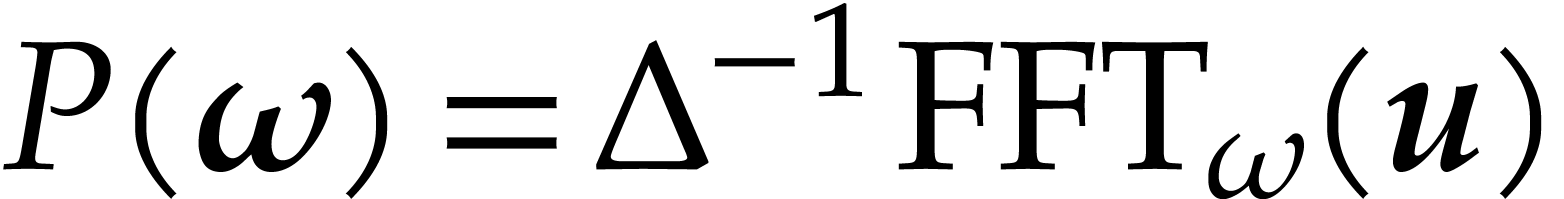

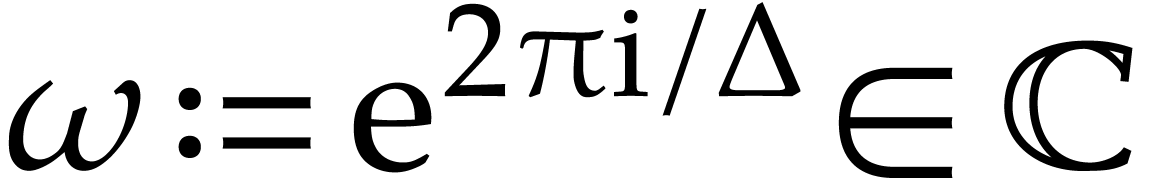

We define the fast Fourier transform of  to be

to be

where  . In particular, we

have

. In particular, we

have  .

.

Proof. Thanks to [18, section 3] an

approximation of  in

in  can

be computed with error

can

be computed with error  in time

in time  . Consider an entry

. Consider an entry  of

of

and let

and let  be the

corresponding approximation. Let

be the

corresponding approximation. Let  ,

where

,

where  and

and  .

Then

.

Then  ,

,  , and

, and  .

We may clearly compute

.

We may clearly compute  in time

in time  . Thanks to Lemma 3, and using

. Thanks to Lemma 3, and using

further operations, we may next compute a

truncation

further operations, we may next compute a

truncation  of

of  with error

with error

.

.

Proof. If  ,

then

,

then  . Otherwise,

. Otherwise,  and we have

and we have

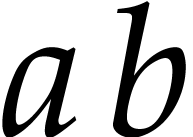

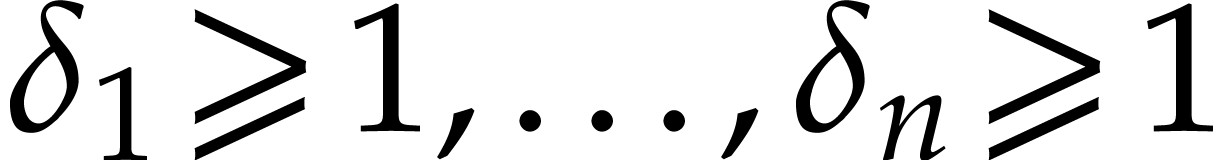

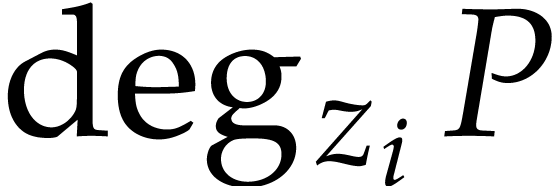

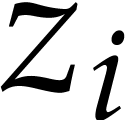

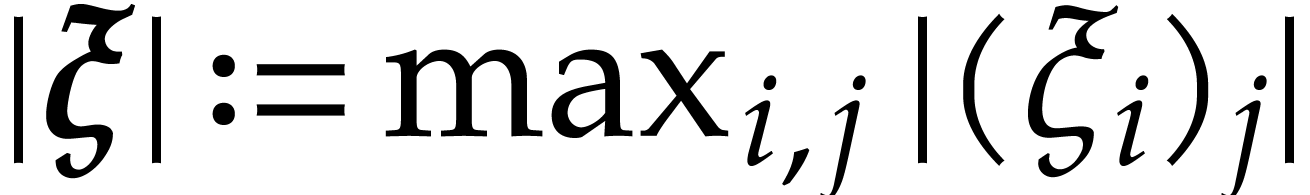

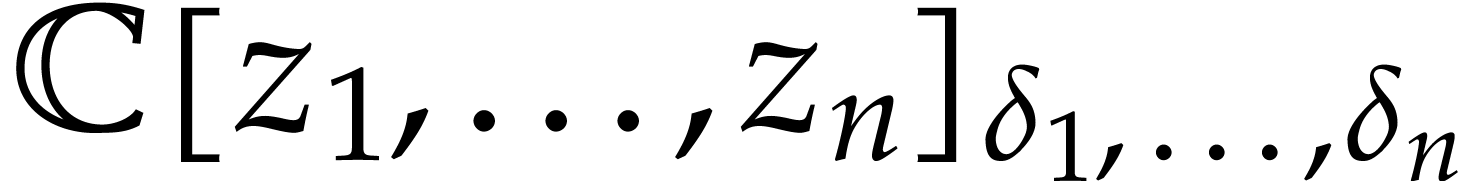

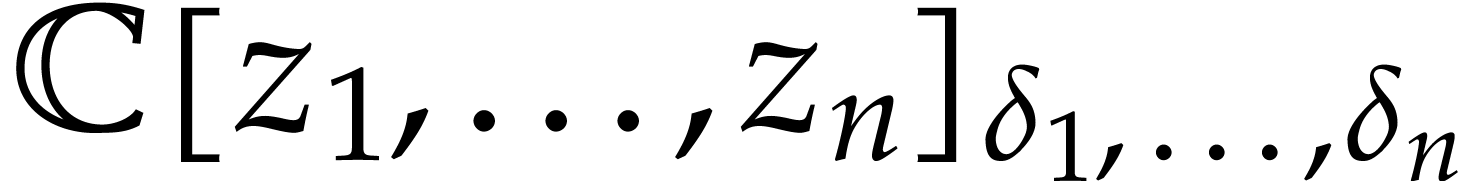

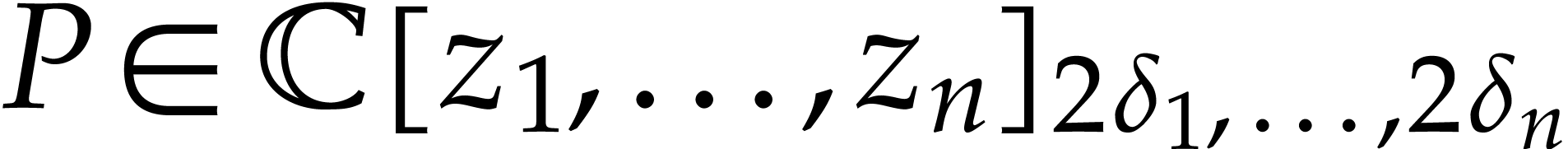

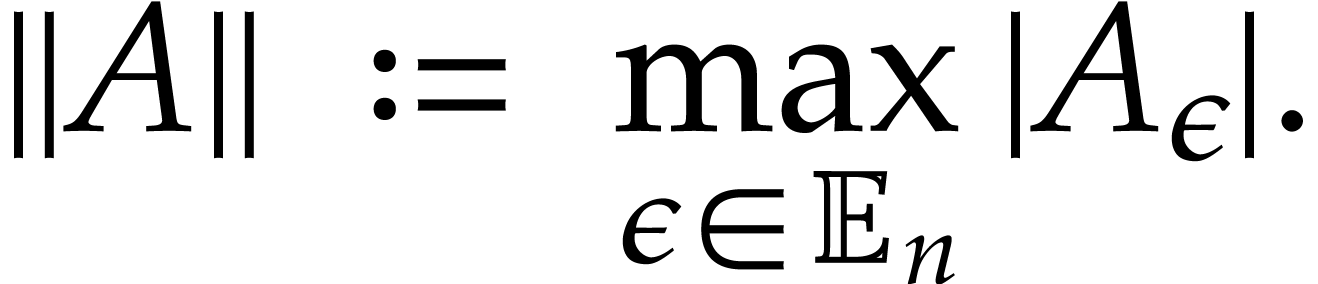

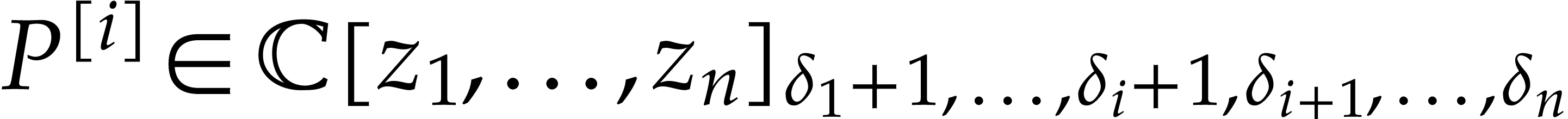

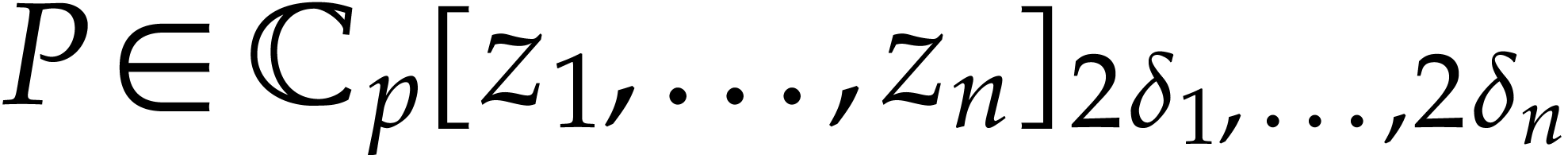

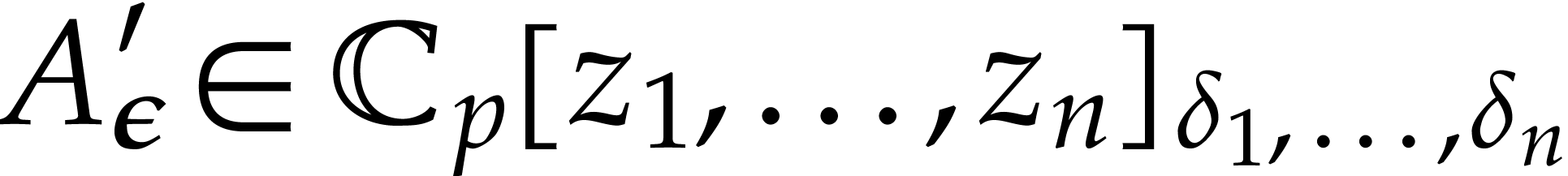

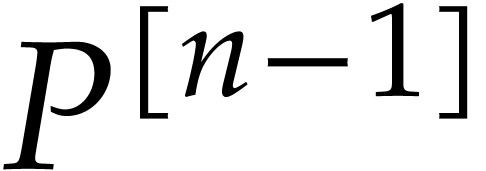

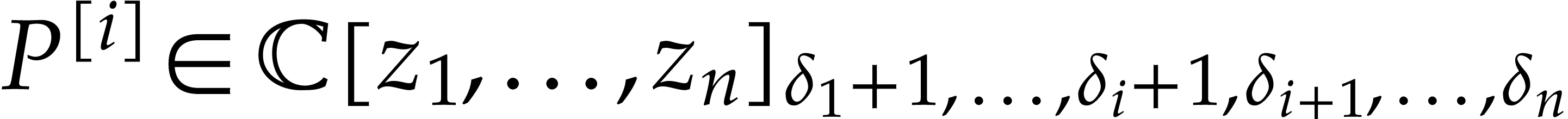

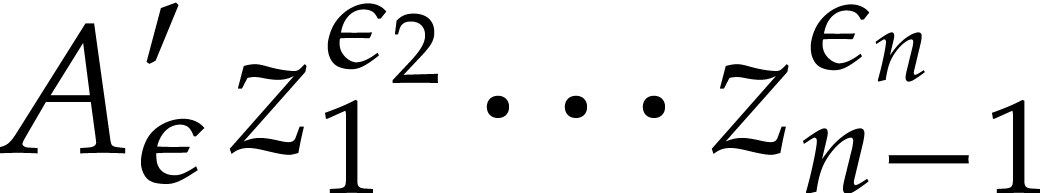

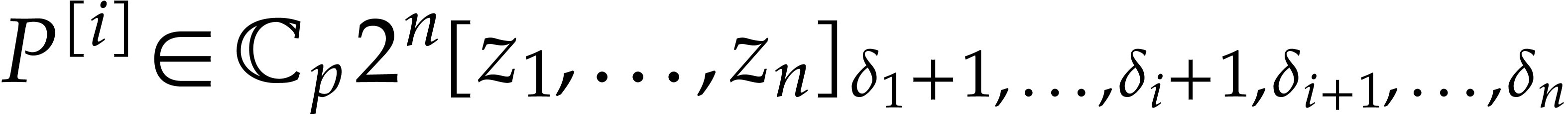

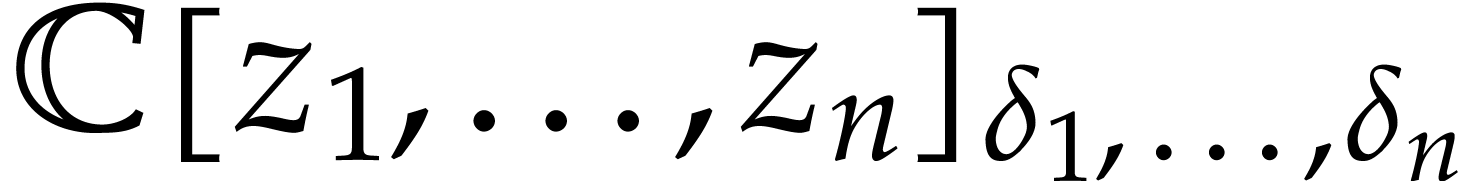

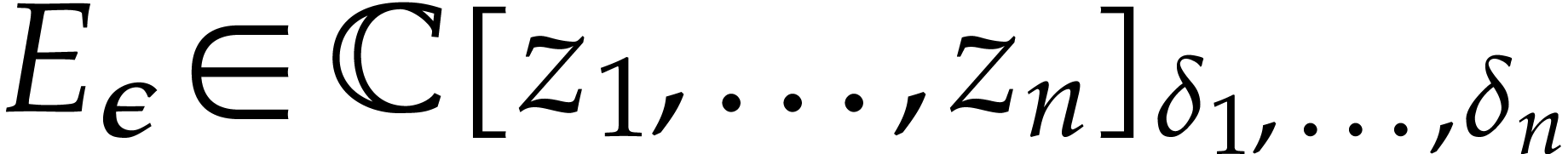

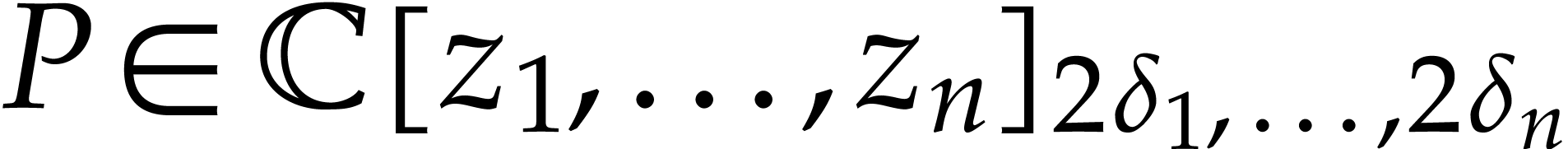

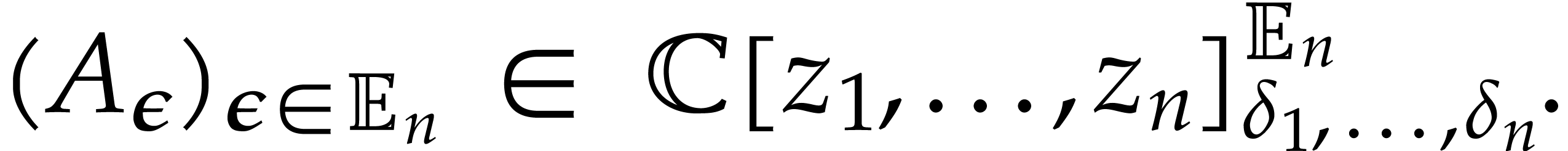

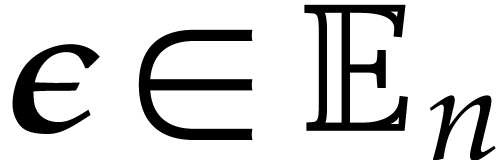

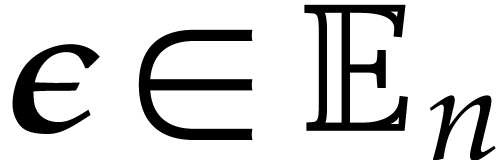

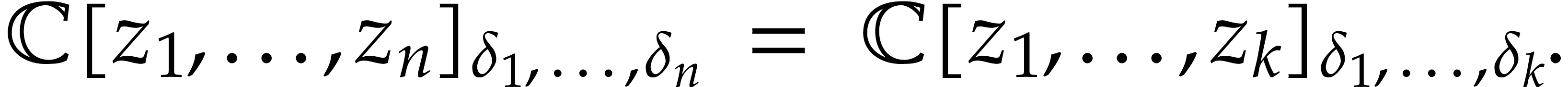

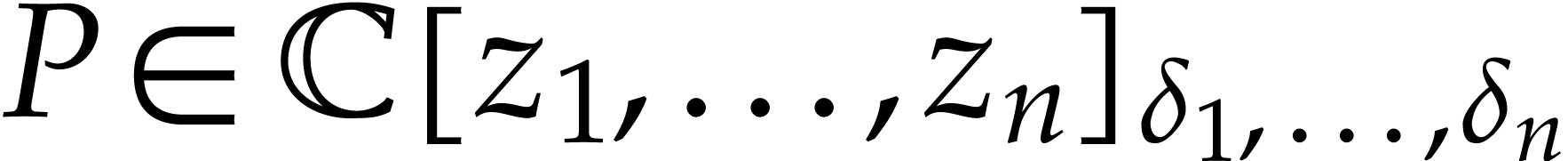

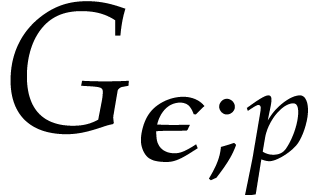

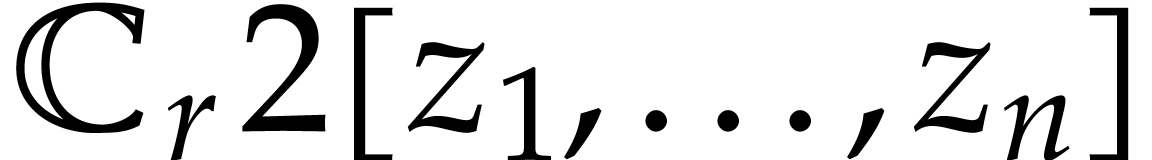

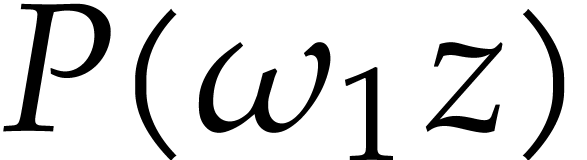

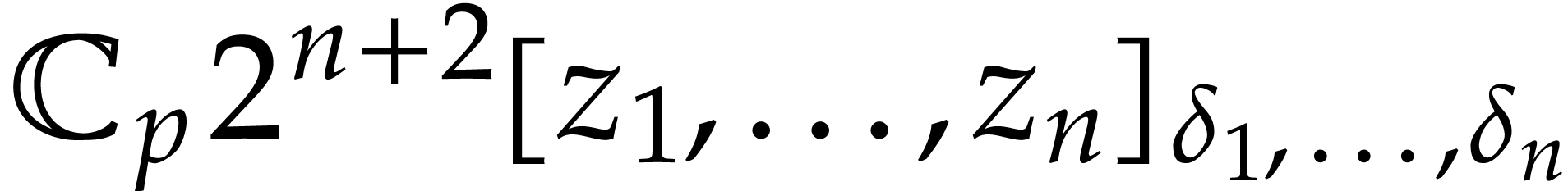

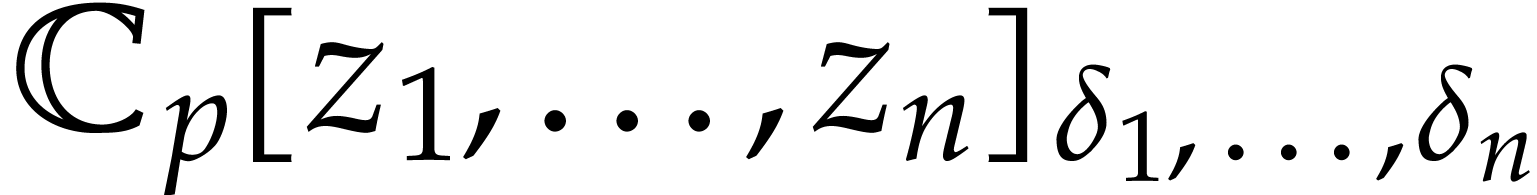

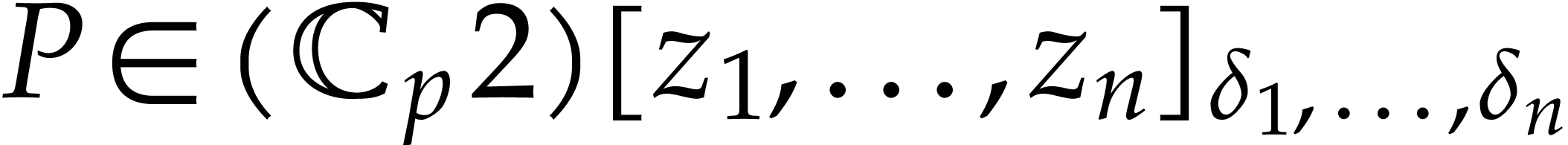

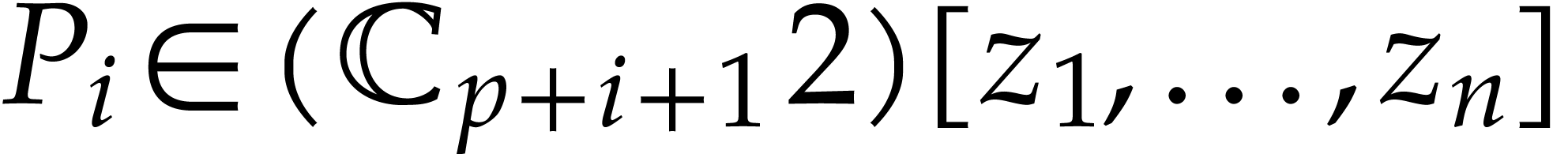

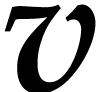

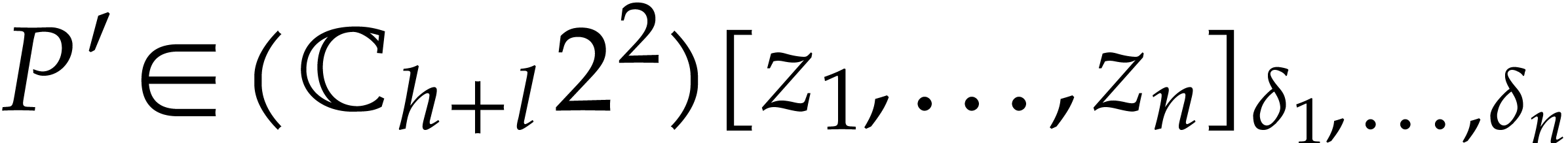

Given integers  , we define

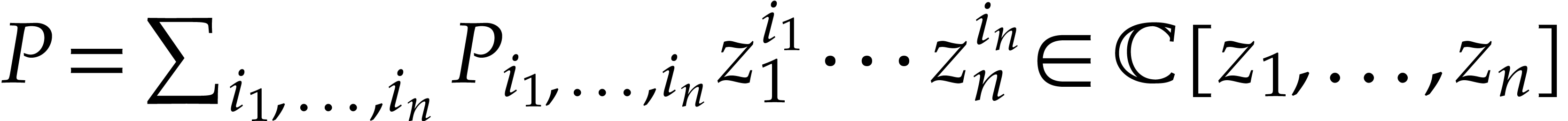

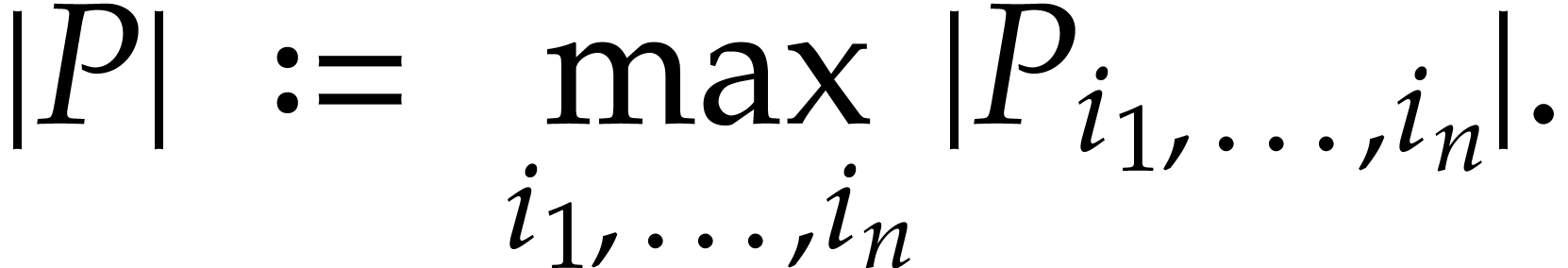

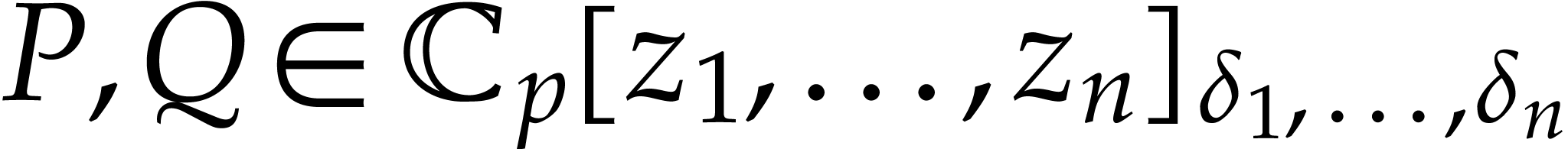

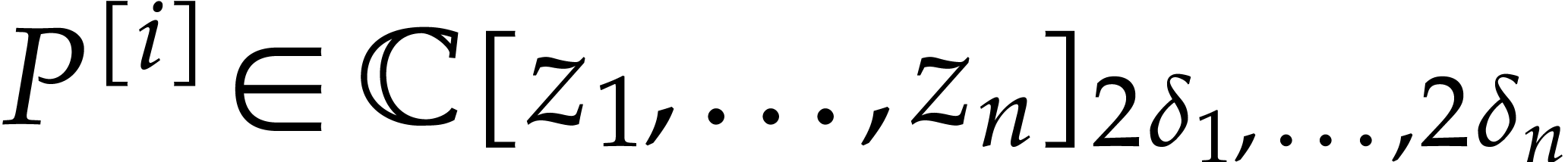

, we define

where  denotes the partial degree of

denotes the partial degree of  in

in  , for

, for  . In this paper, a dense

representation will be used for univariate and multivariate polynomials.

This means that a polynomial

. In this paper, a dense

representation will be used for univariate and multivariate polynomials.

This means that a polynomial  is stored as a

vector of size

is stored as a

vector of size  made of the coefficients of the

terms of

made of the coefficients of the

terms of  of partial degree

of partial degree  in

in  , for

, for  . Precisely, when

. Precisely, when  ,

a polynomial

,

a polynomial  is stored as the vector

is stored as the vector  . When

. When  , a polynomial

, a polynomial  will be

regarded as a univariate polynomial in

will be

regarded as a univariate polynomial in  whose

coefficients are polynomials in

whose

coefficients are polynomials in  .

.

Given a polynomial  , we

define

, we

define

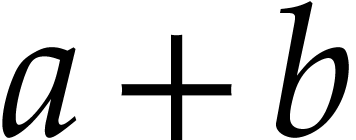

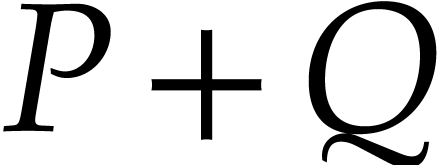

Given polynomials  the sum

the sum  can be computed exactly in time

can be computed exactly in time  .

The product

.

The product  can be computed exactly in time

can be computed exactly in time  using Kronecker substitution; see [5,

Chapter 8]. In addition we have

using Kronecker substitution; see [5,

Chapter 8]. In addition we have  .

.

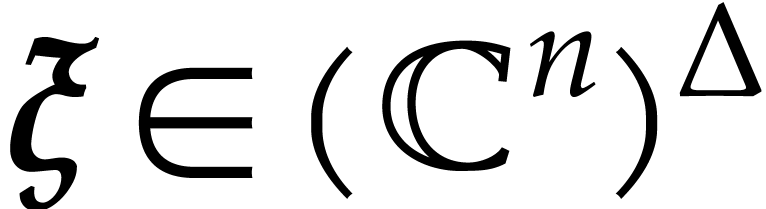

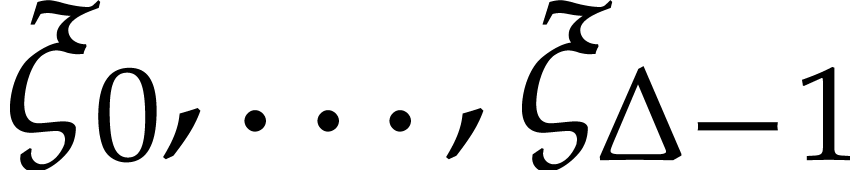

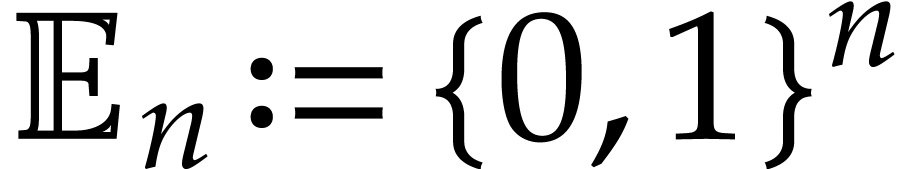

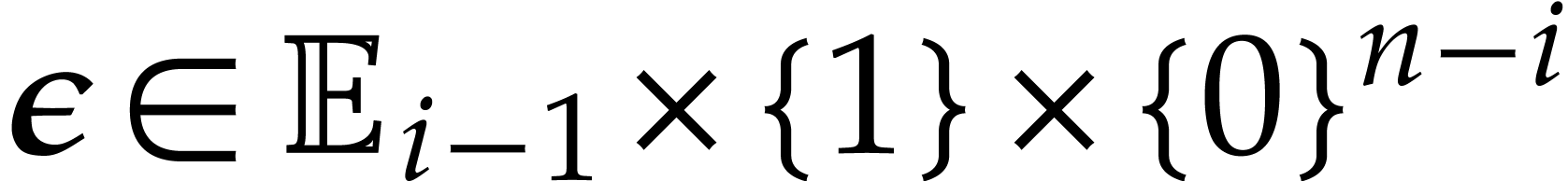

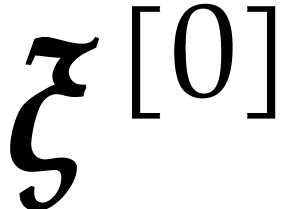

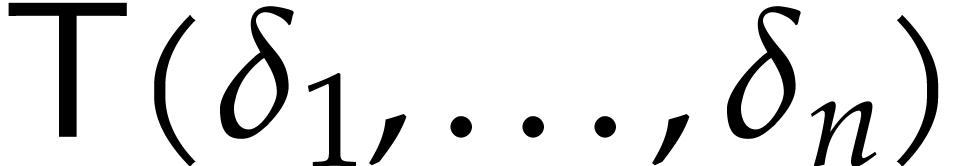

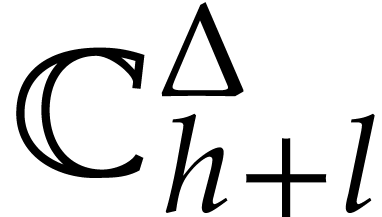

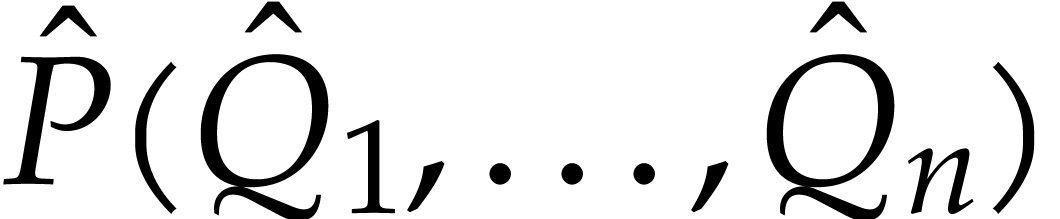

Given integers  , we let

, we let  and consider a tuple of points

and consider a tuple of points

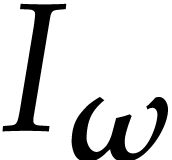

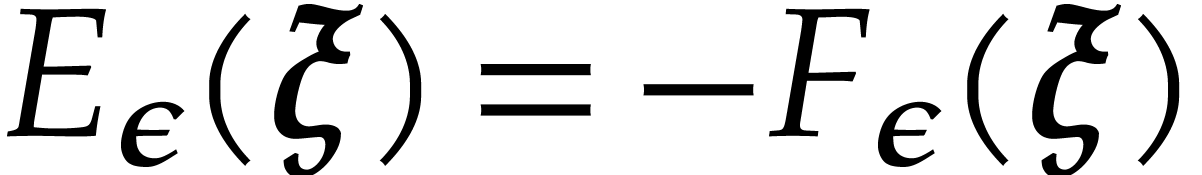

We define  and call

and call

the vanishing ideal of  .

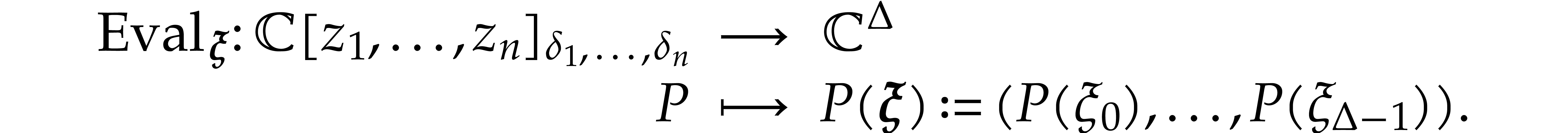

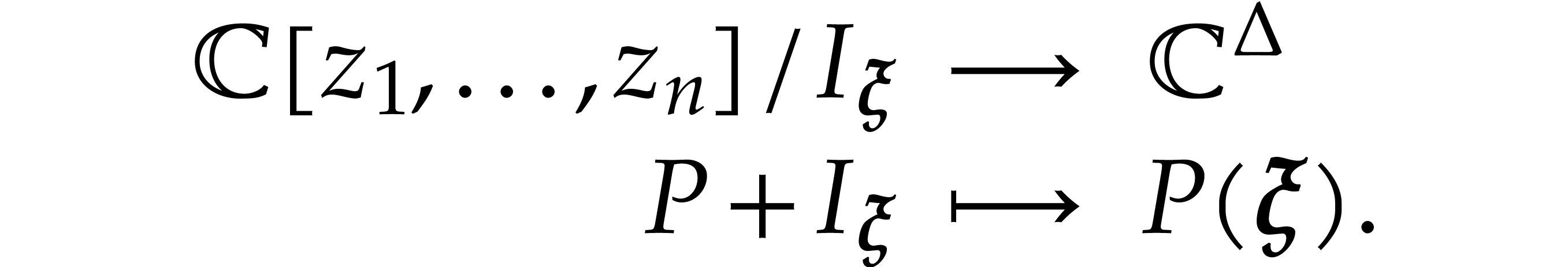

We also define the evaluation map

.

We also define the evaluation map

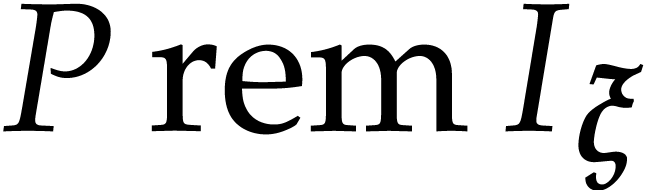

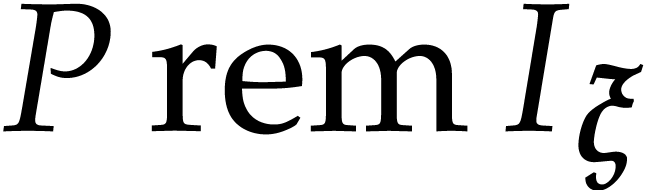

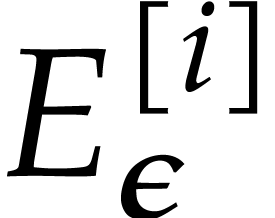

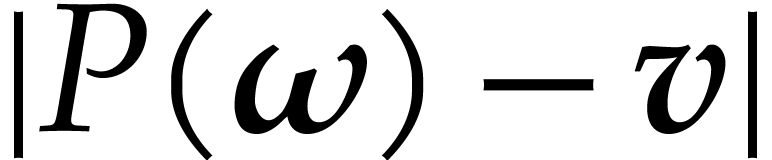

We refer to the computation of  as the problem of

multi-point evaluation. The computation of

as the problem of

multi-point evaluation. The computation of  is called the interpolation problem.

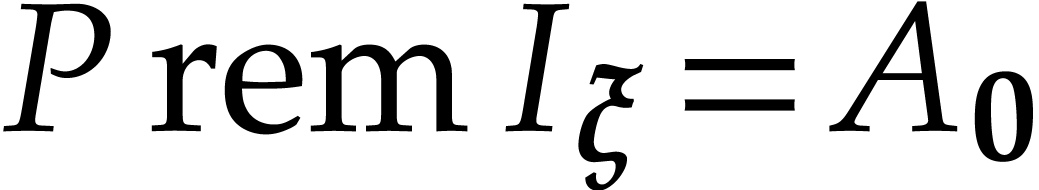

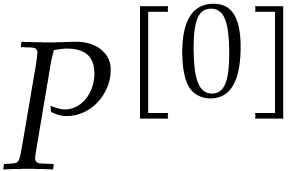

is called the interpolation problem.  is

a bijection for a Zariski dense subset of tuples

is

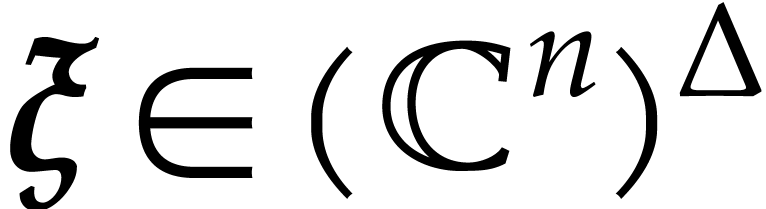

a bijection for a Zariski dense subset of tuples  . Whenever this is the case, the points

. Whenever this is the case, the points  are pairwise distinct, so we have a natural bijection

are pairwise distinct, so we have a natural bijection

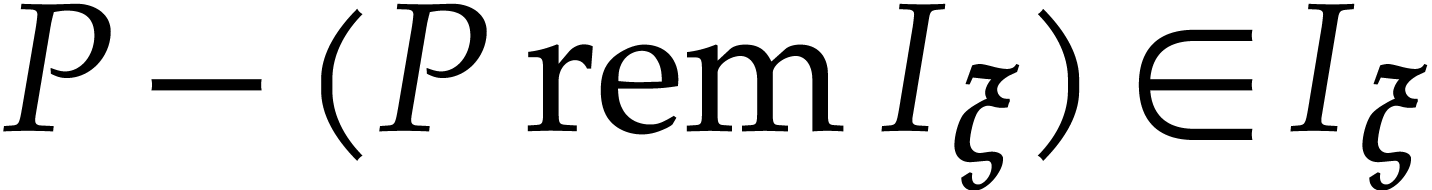

This allows us to use polynomials in  as

canonical representatives of residue classes in

as

canonical representatives of residue classes in  . In particular, given a polynomial

. In particular, given a polynomial  , we define

, we define  to be the

unique polynomial in

to be the

unique polynomial in  with

with  . For special tuples

. For special tuples  ,

called spiroids, we will show in this section that

,

called spiroids, we will show in this section that  can be computed efficiently.

can be computed efficiently.

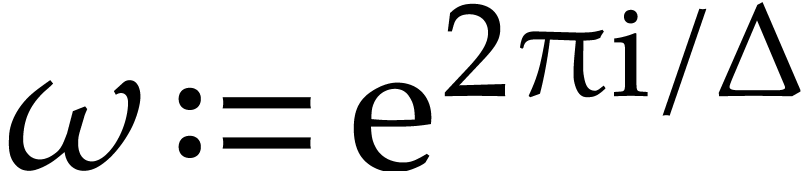

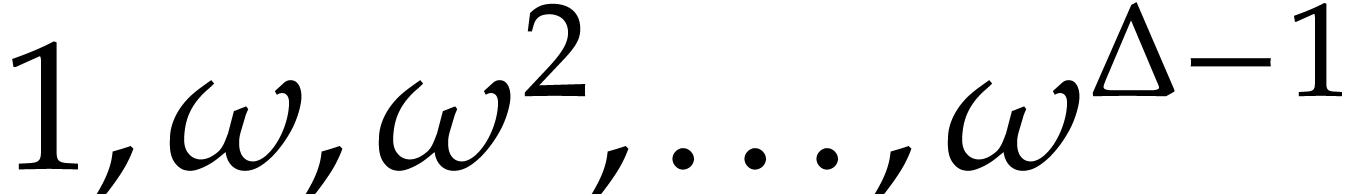

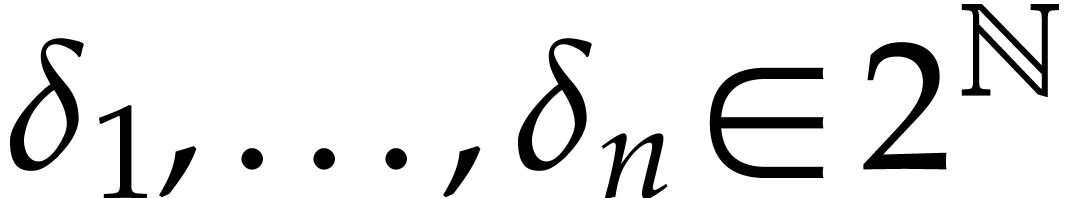

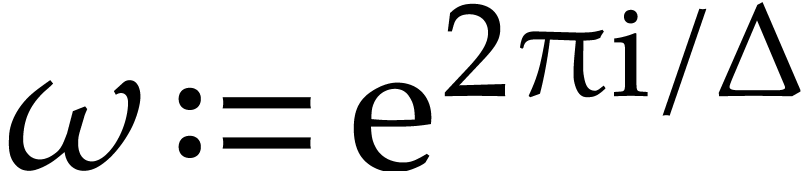

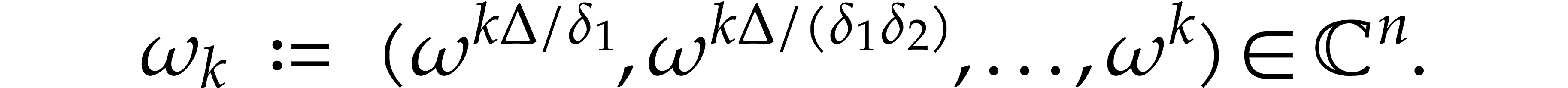

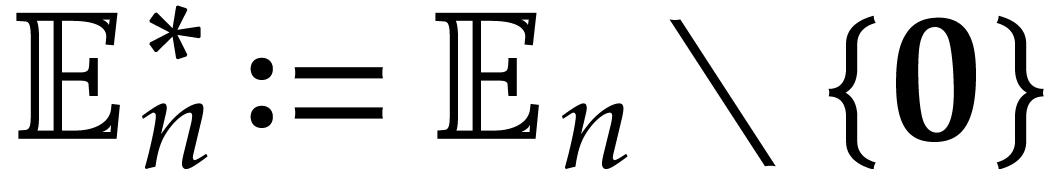

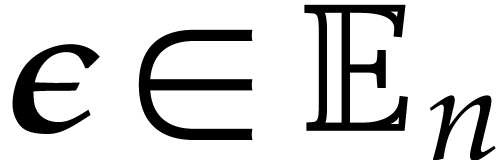

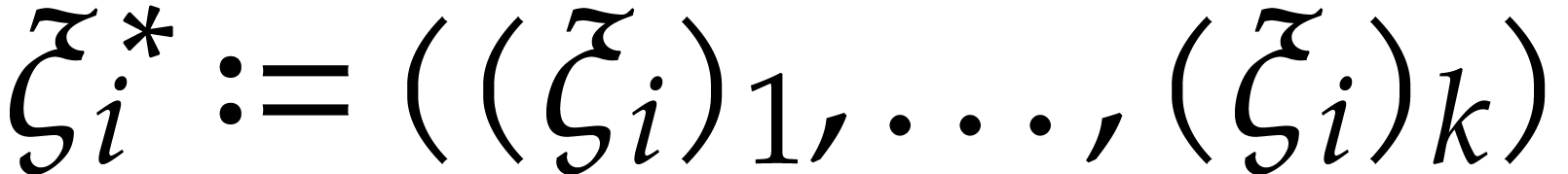

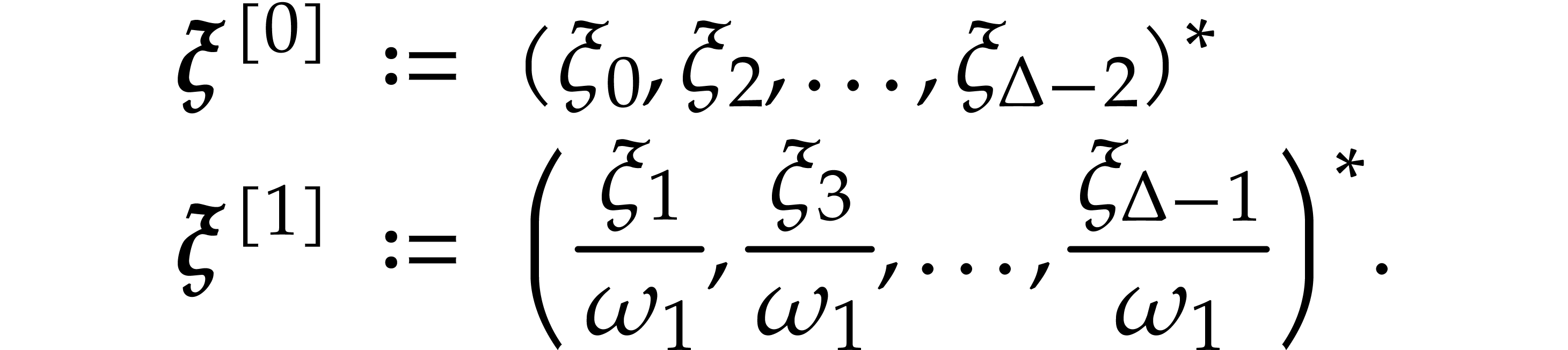

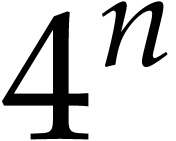

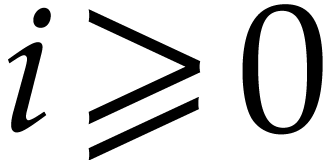

Assume from now that  are powers of two and let

are powers of two and let

be the standard primitive

be the standard primitive  -th root of unity in

-th root of unity in  .

For each

.

For each  , we let

, we let

We call the tuple  a regular spiroid.

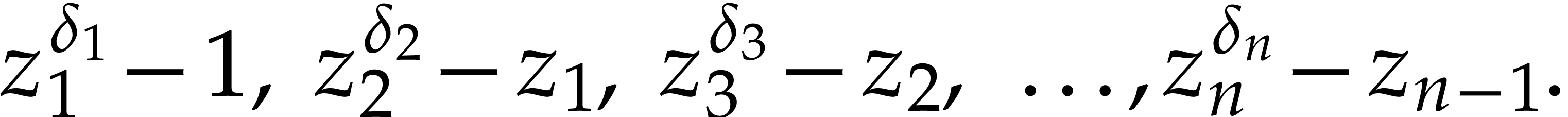

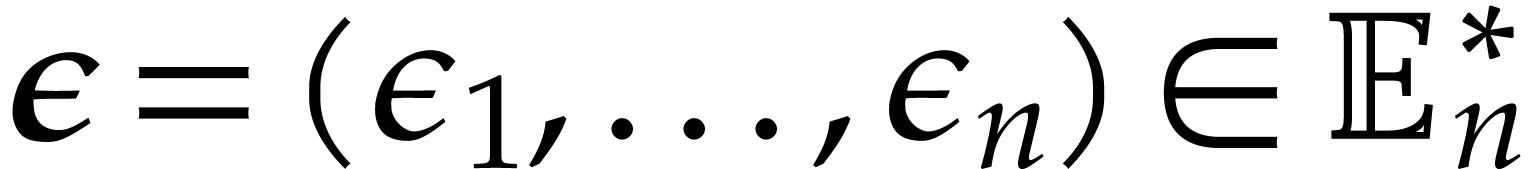

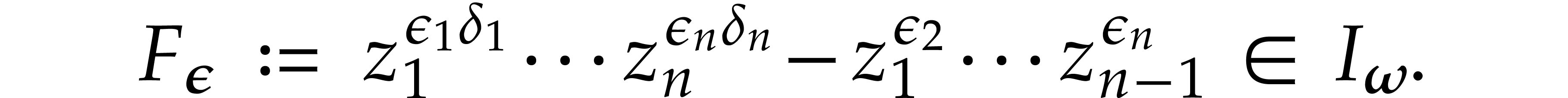

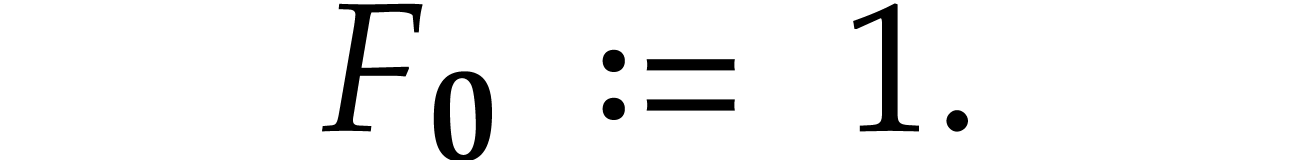

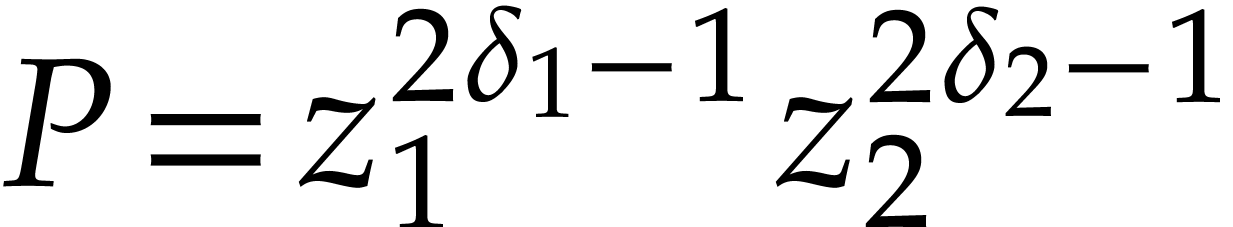

The vanishing ideal

a regular spiroid.

The vanishing ideal  of this tuple of points is

generated by the polynomials

of this tuple of points is

generated by the polynomials

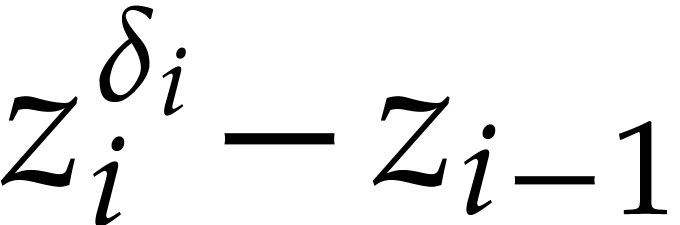

|

(1) |

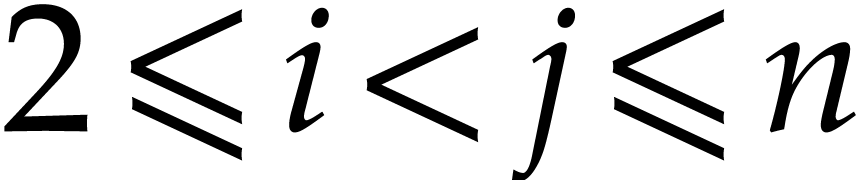

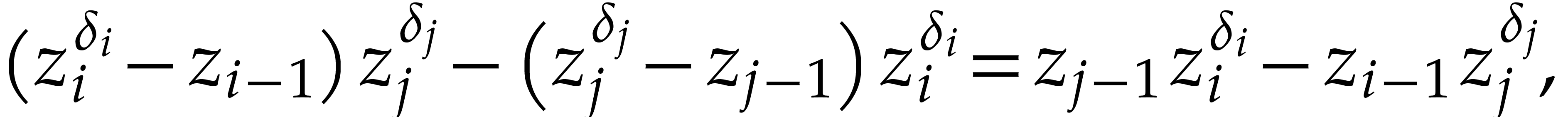

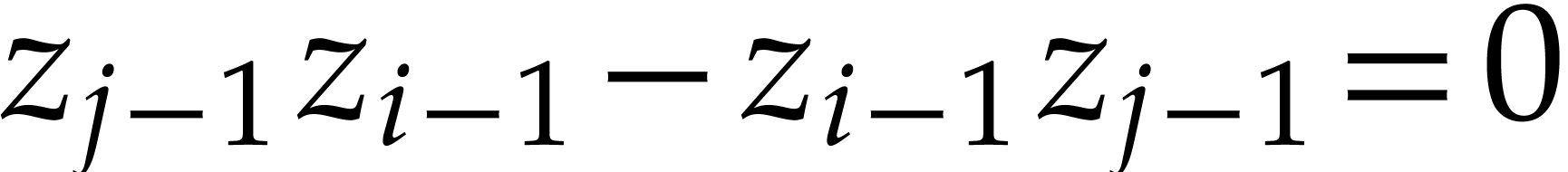

A straightforward computation shows that these generators actually form

a Gröbner basis for the grevlex monomial ordering. For instance,

for  , the

, the  -polynomial of

-polynomial of  and

and  is

is

which reduces to  . In

particular, the monomials in

. In

particular, the monomials in  are reduced.

are reduced.

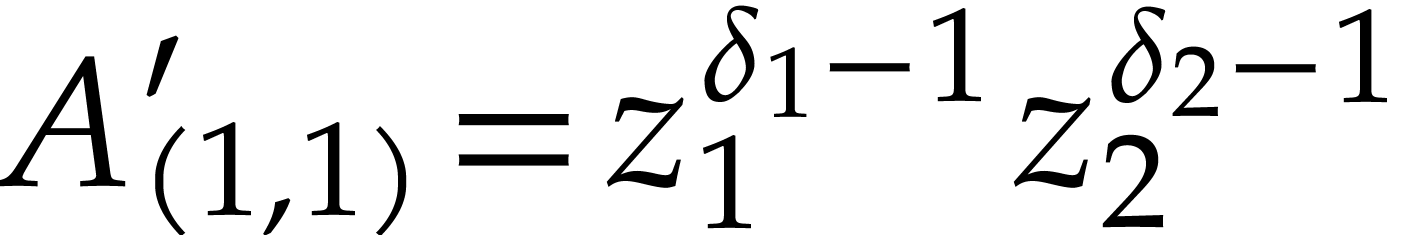

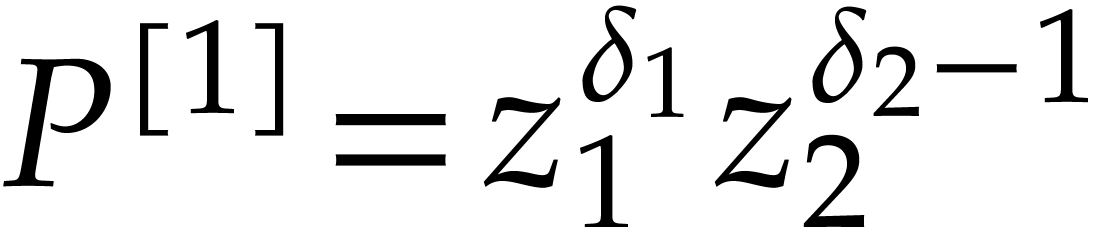

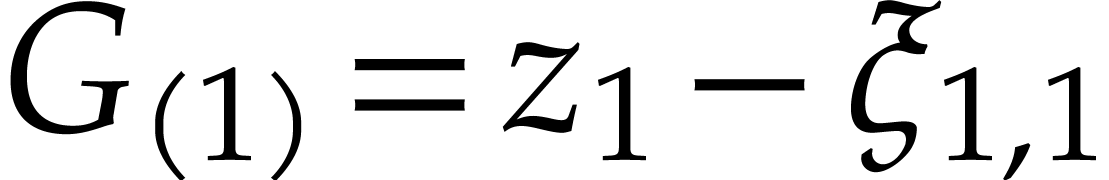

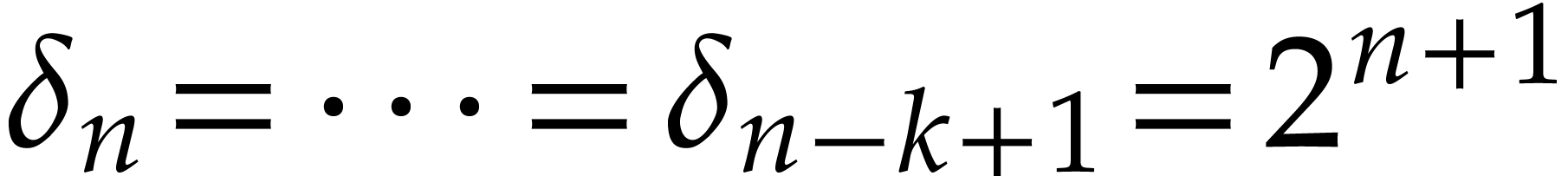

Let  ,

,  , and

, and  .

For

.

For  , we have

, we have

For convenience, we also set

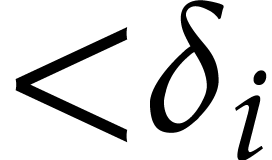

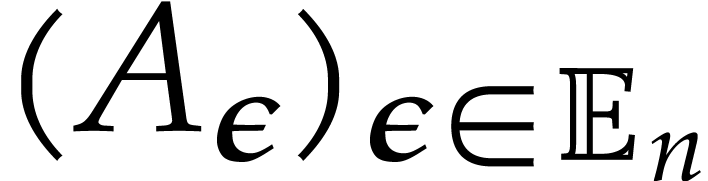

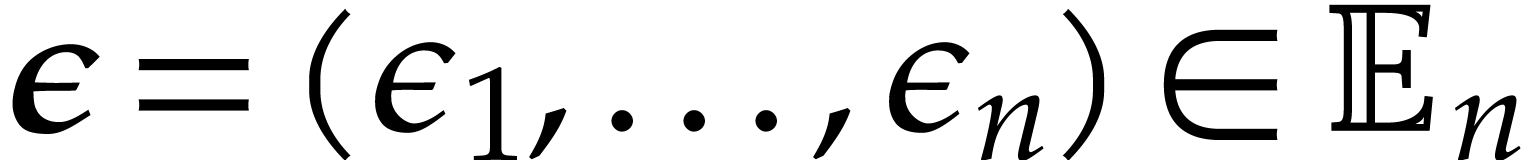

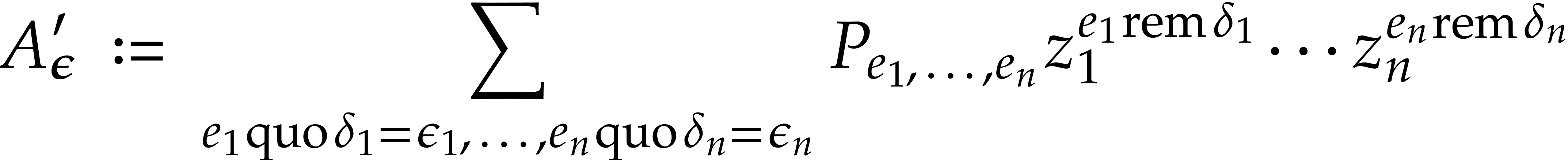

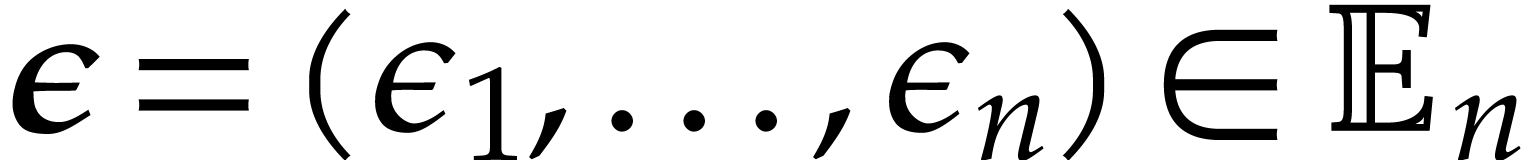

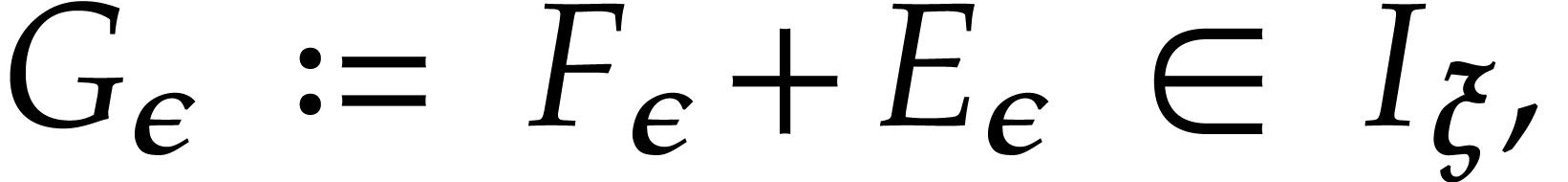

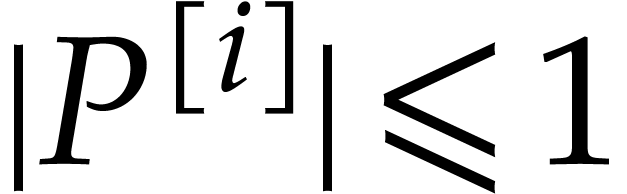

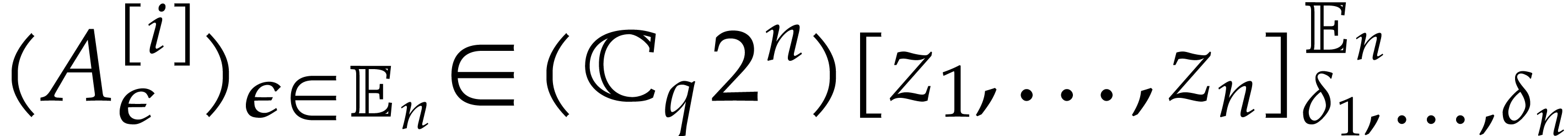

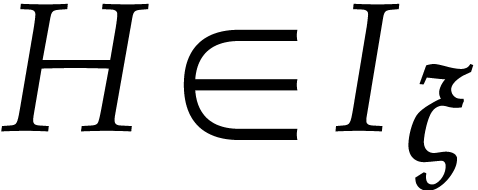

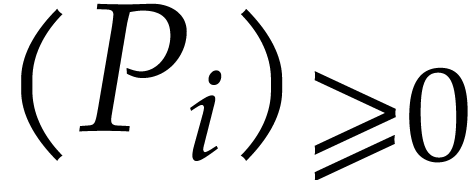

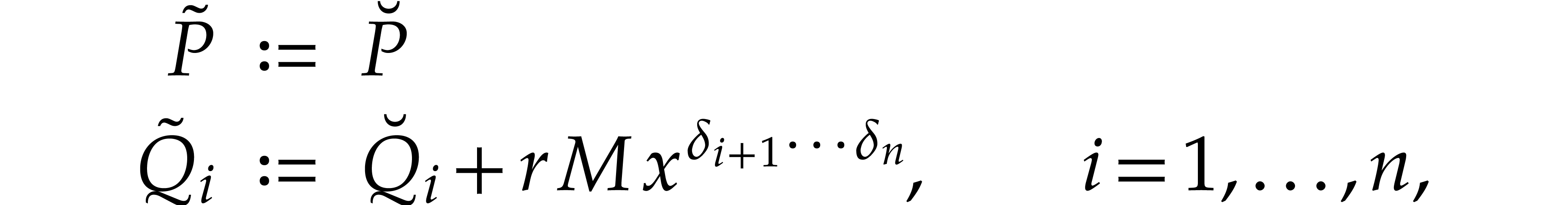

Given  and a family

and a family

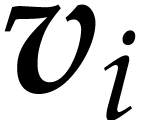

we say that  is an extended reduction of

is an extended reduction of

modulo

modulo  if

if

Since  , we have

, we have  . We further define

. We further define

Given  we aim at computing an extended reduction

of

we aim at computing an extended reduction

of  by

by  .

As a first step we begin with polynomials

.

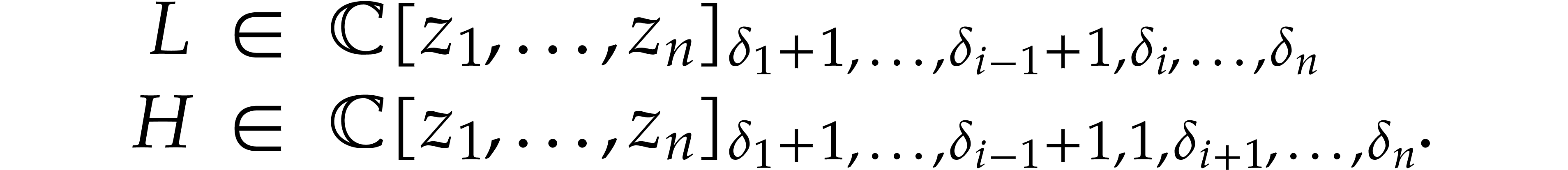

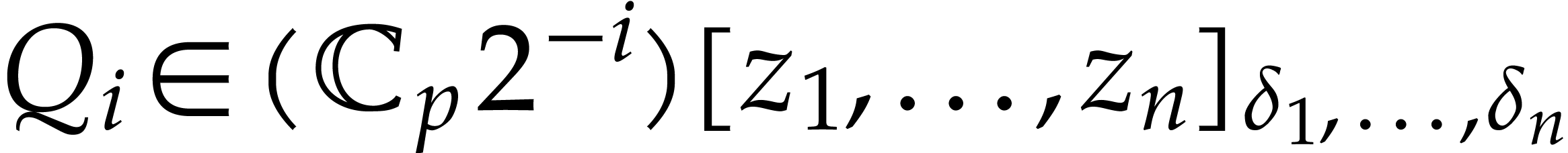

As a first step we begin with polynomials  in

in

.

.

Proof. Since  is

generated by binomial polynomials

is

generated by binomial polynomials  is a monomial.

The defining equations

is a monomial.

The defining equations  further imply that

further imply that  are

invertible in

are

invertible in  .

.

The support  of a polynomial

of a polynomial  is the set of its monomials with a non-zero coefficient.

We say that the monomials of

is the set of its monomials with a non-zero coefficient.

We say that the monomials of  are pairwise

distinct modulo

are pairwise

distinct modulo  when any two distinct monomials

of

when any two distinct monomials

of  have distinct projections in

have distinct projections in  .

.

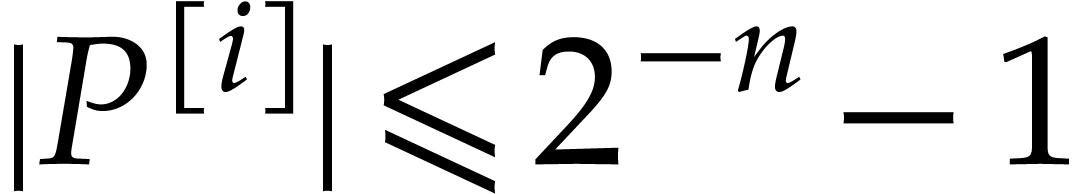

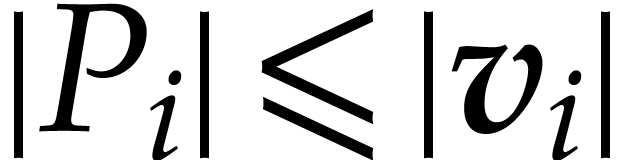

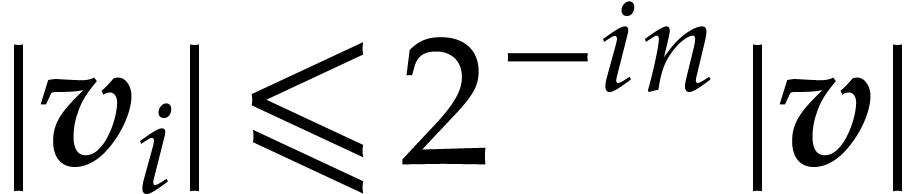

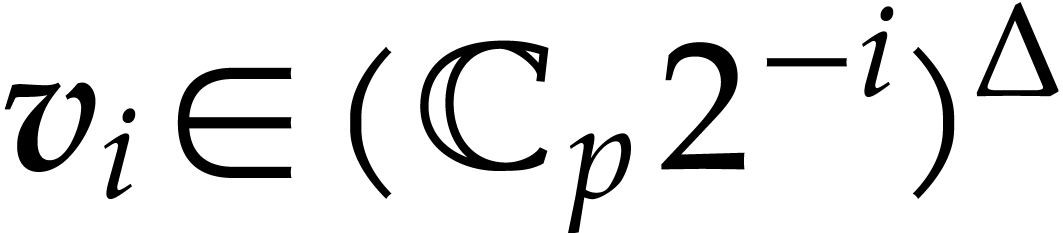

be such that the monomials of its support are

pairwise distinct modulo

be such that the monomials of its support are

pairwise distinct modulo  .

Let

.

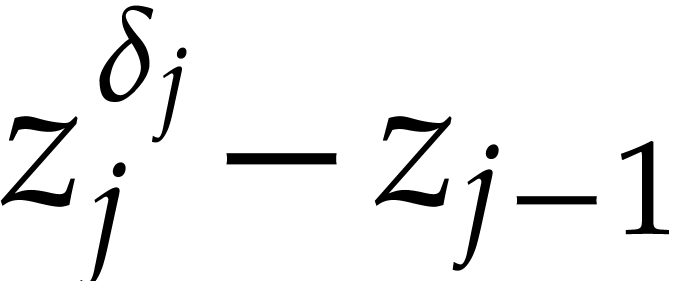

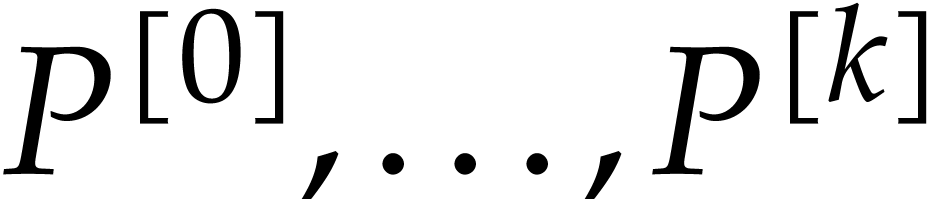

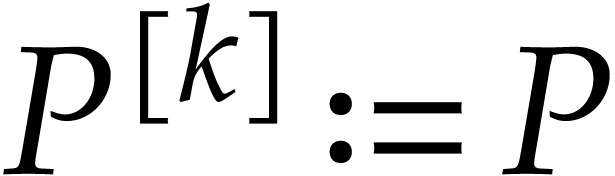

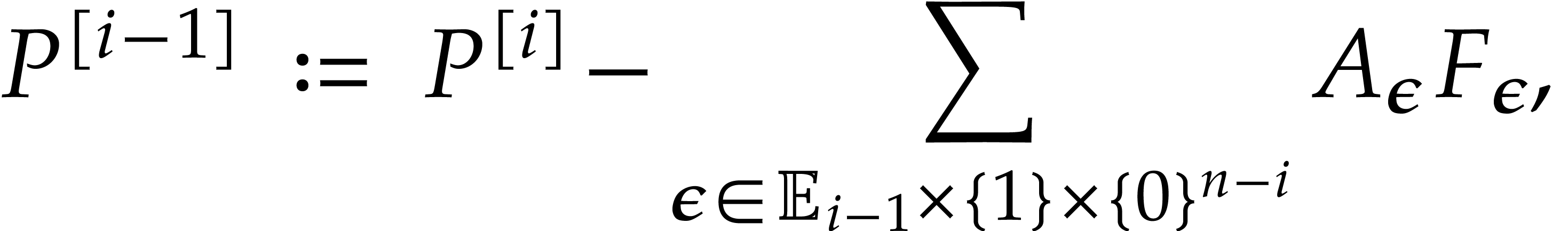

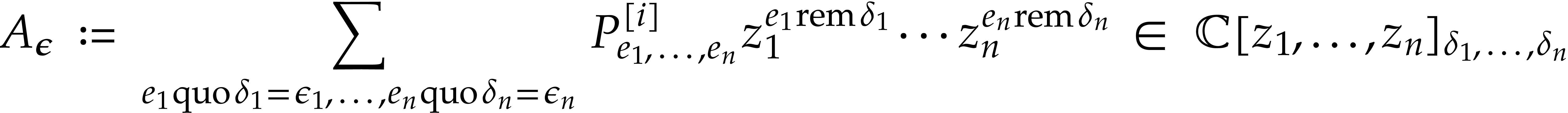

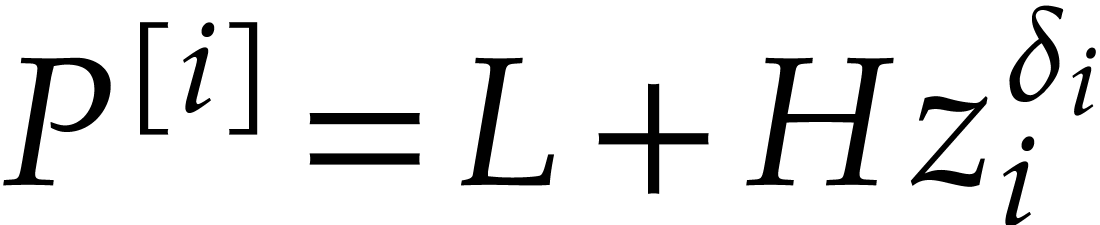

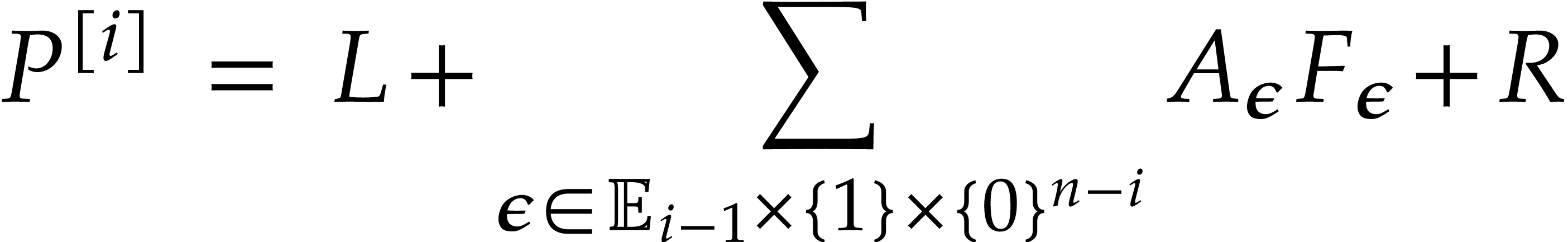

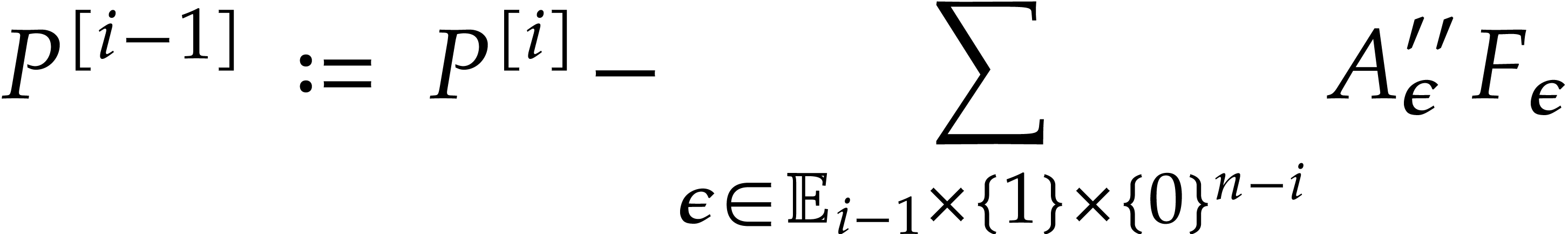

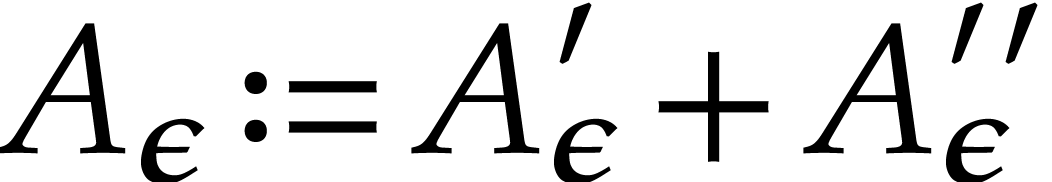

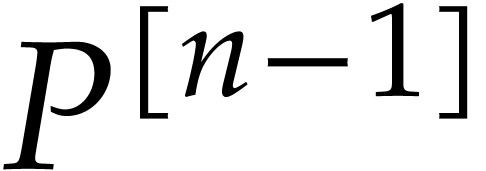

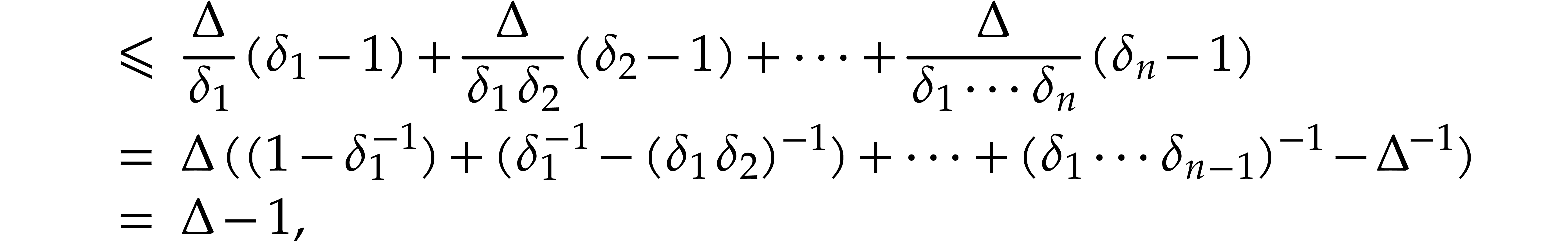

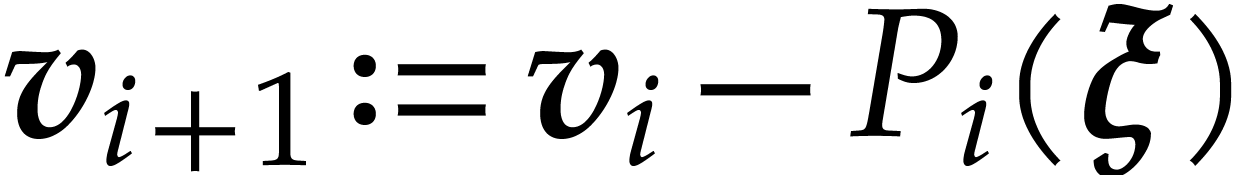

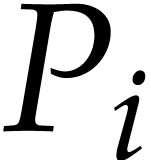

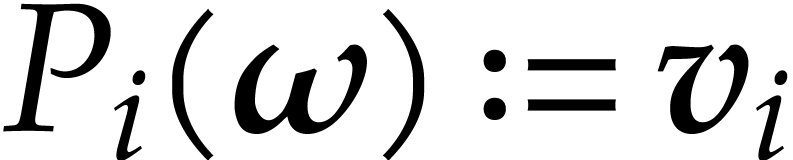

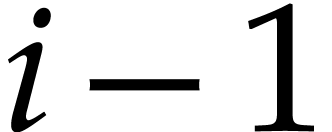

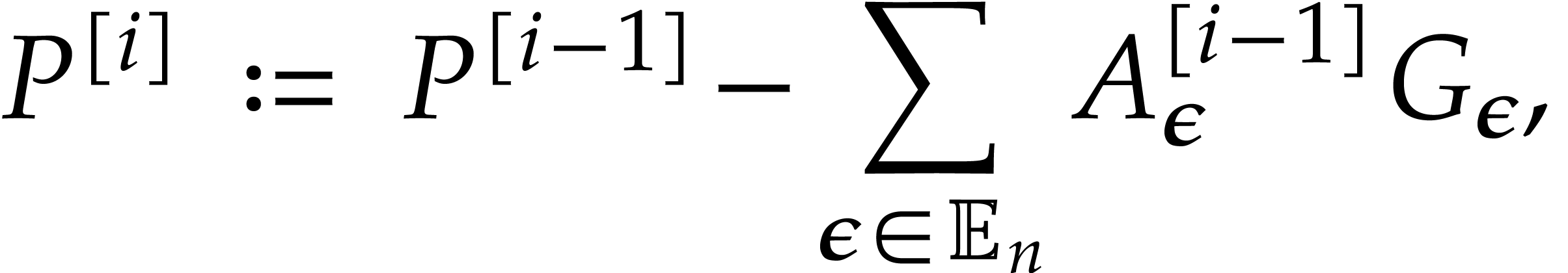

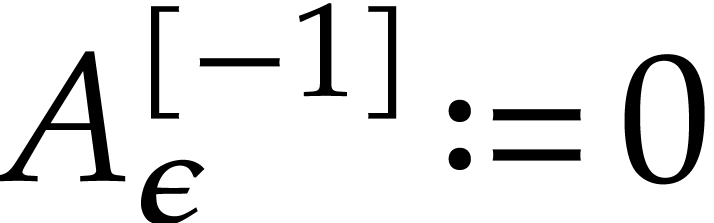

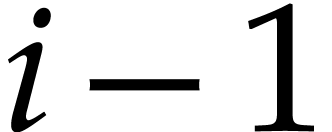

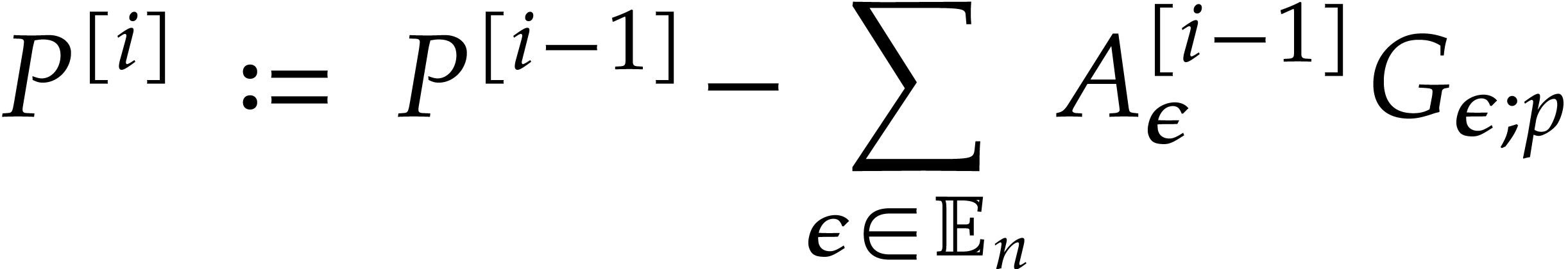

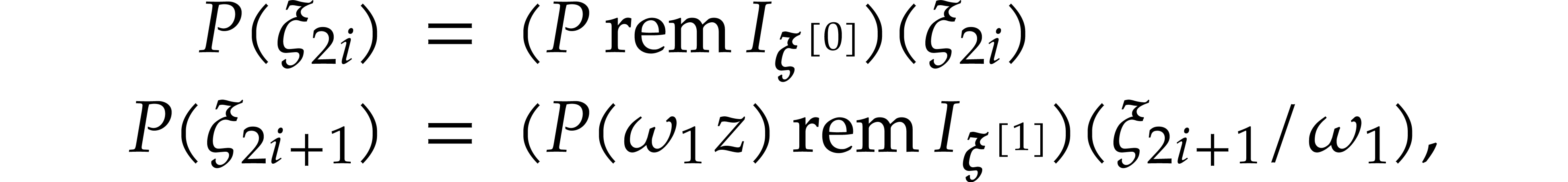

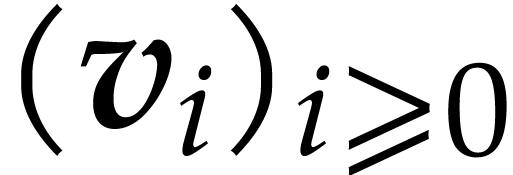

Let  be defined recursively as follows:

be defined recursively as follows:  , and

, and

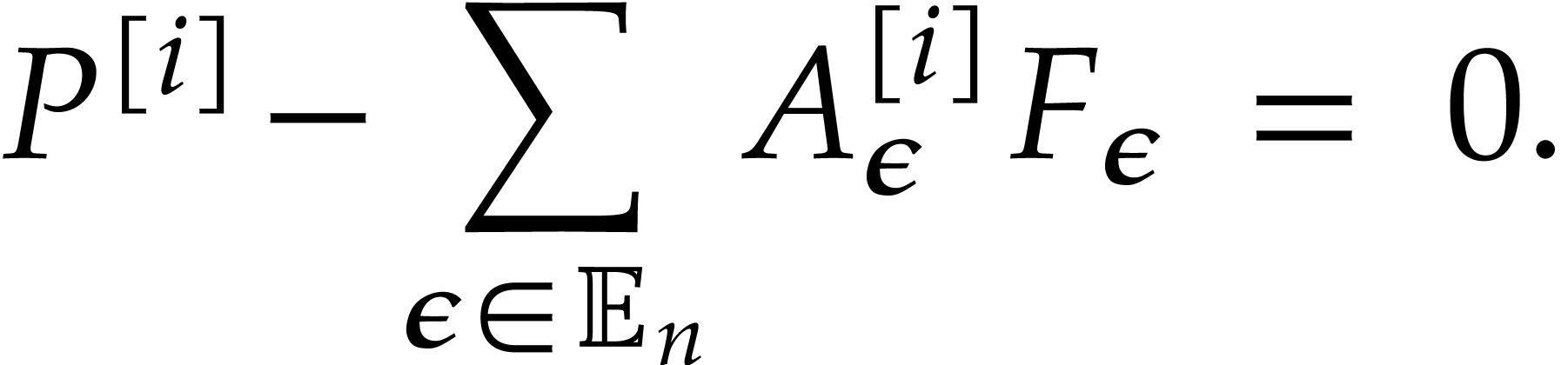

|

(2) |

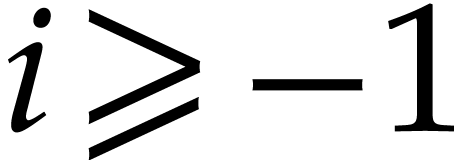

where

for  . For

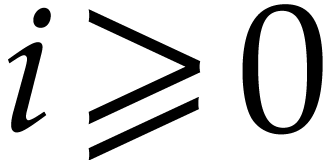

. For  , the following properties hold:

, the following properties hold:

,

,

the monomials of the support of  are

pairwise distinct modulo

are

pairwise distinct modulo  ,

,

the coefficients of  are coefficients of

are coefficients of

.

.

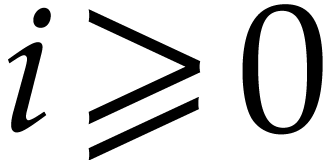

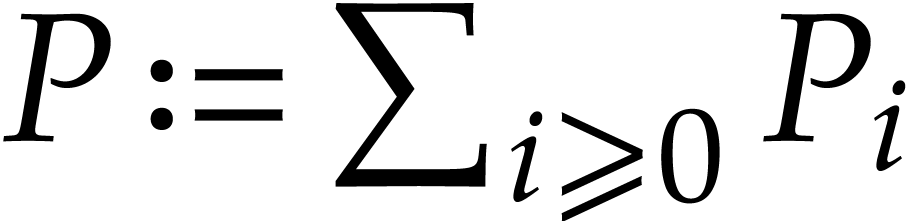

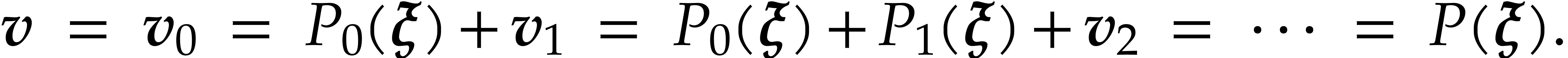

Letting  for

for  and

and

, the family

, the family  is an extended reduction of

is an extended reduction of  .

.

Proof. The proof is done by induction on  . The properties are clear for

. The properties are clear for

. Let us assume that they

hold for

. Let us assume that they

hold for  . We decompose

. We decompose  into

into  with

with

We verify that

where

Since the monomials of the support of  are

pairwise distinct modulo

are

pairwise distinct modulo  ,

the supports of

,

the supports of  and

and  are

disjoint. In particular the monomials of the support of

are

disjoint. In particular the monomials of the support of  are pairwise distinct modulo

are pairwise distinct modulo  ,

and the non-zero coefficients of

,

and the non-zero coefficients of  are

coefficients of

are

coefficients of  .

.

Finally unrolling

which constitutes the extended reduction of  .

.

The reduction of a general  modulo

modulo  can be performed efficiently by the following algorithm.

can be performed efficiently by the following algorithm.

Algorithm

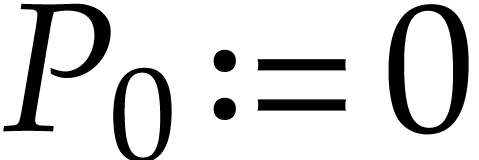

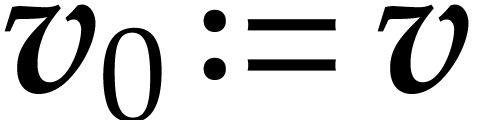

For all  set

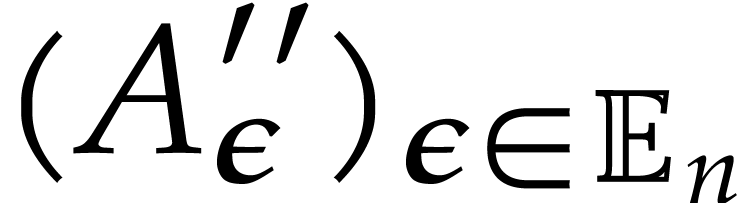

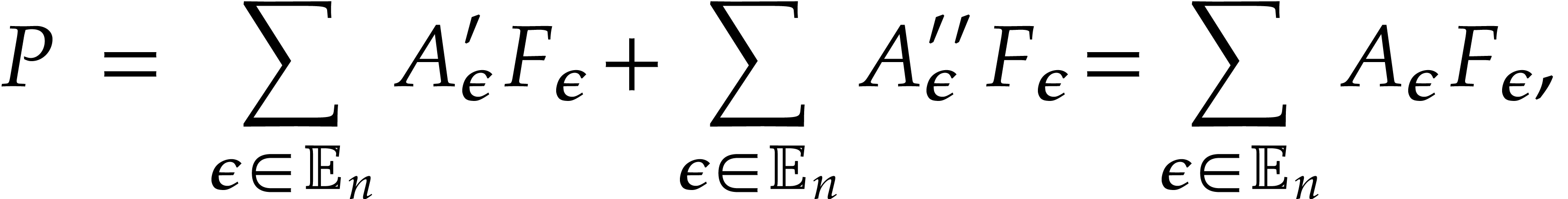

set

and compute

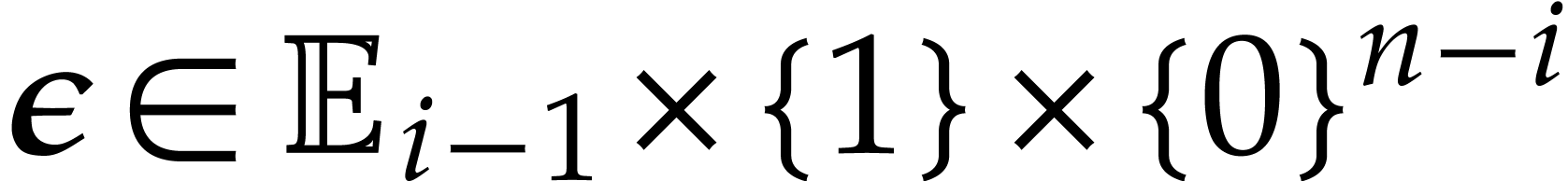

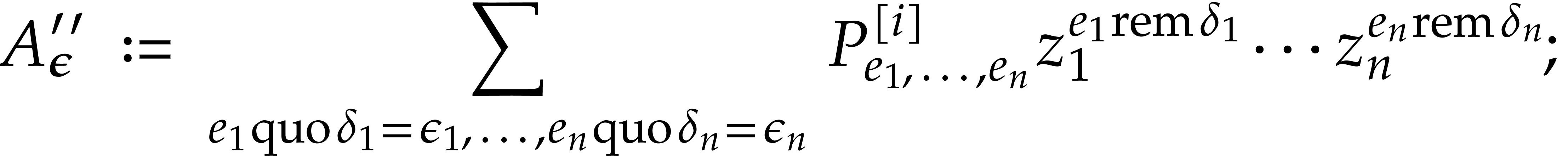

Let  for

for  ,

and for

,

and for  from

from  down to

down to  do:

do:

For all  , set

, set

Compute  .

.

Let  , compute

, compute  for

for  ,

and return

,

and return  .

.

.

.

Proof. For all  ,

we have

,

we have  . Let us examine the

particular case where

. Let us examine the

particular case where  restricts to a single term

restricts to a single term

for some

for some  .

By Lemma 7, the monomials of the support of

.

By Lemma 7, the monomials of the support of  are pairwise distinct modulo

are pairwise distinct modulo  ,

so Lemma 8 implies the following properties, for

,

so Lemma 8 implies the following properties, for  :

:

,

,

the coefficients of  are coefficients of

are coefficients of

, hence of

, hence of  ,

,

is an extended reduction of

is an extended reduction of  .

.

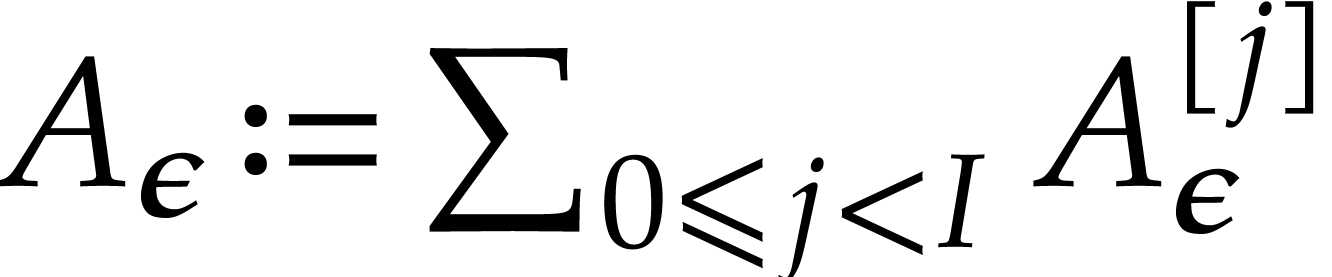

Since the operations in step 2 are linear with respect to the

coefficients of  , the general

case where

, the general

case where  is a sum of

is a sum of  terms of the form

terms of the form  satisfies the following

properties:

satisfies the following

properties:

,

,

,

,

is an extended reduction of

is an extended reduction of  .

.

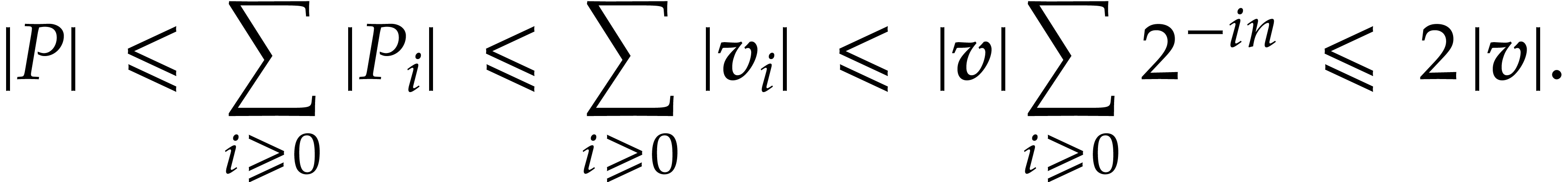

On the other hand step 1 yields

So the correctness proof is completed by noting that

and  . As for the complexity

analysis, step 1 takes time

. As for the complexity

analysis, step 1 takes time  .

Step 2 runs in time

.

Step 2 runs in time

The cost of step 3 does not exceed  .

.

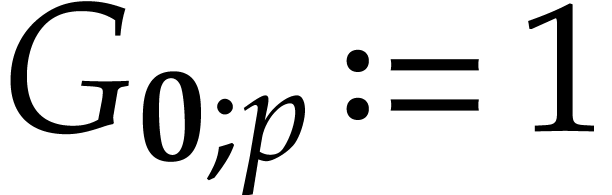

Example. Let  and

and  . With the notation as in Algorithm

1, the only non-zero

. With the notation as in Algorithm

1, the only non-zero  is

is  , and we have

, and we have  . It follows that all the

. It follows that all the  are all

are all  but

but  ,

so we have

,

so we have  . The extended

reduction of

. The extended

reduction of  is

is

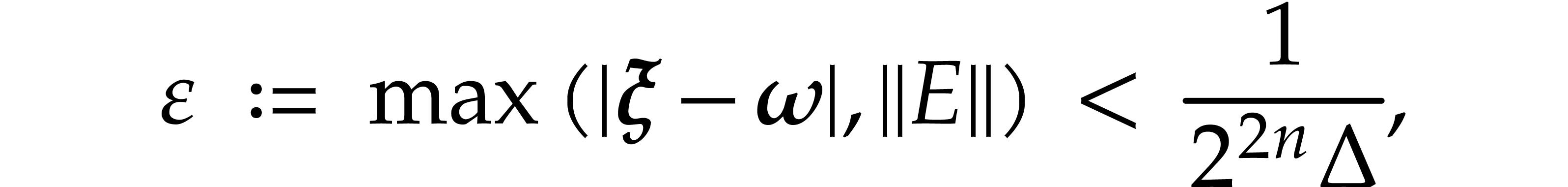

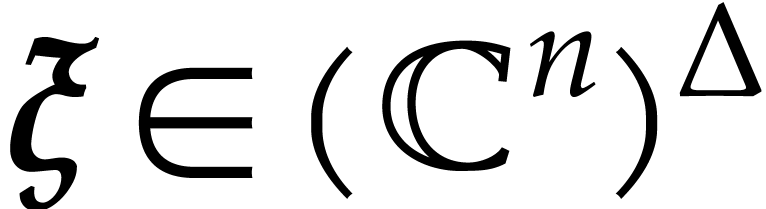

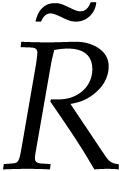

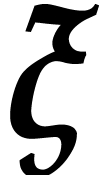

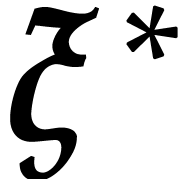

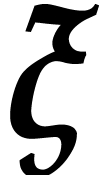

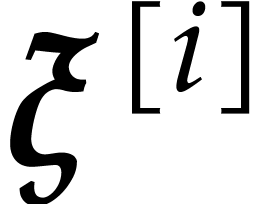

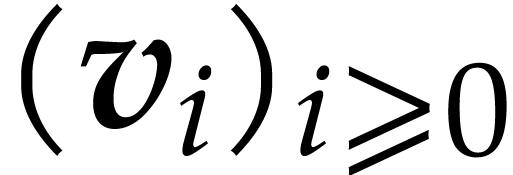

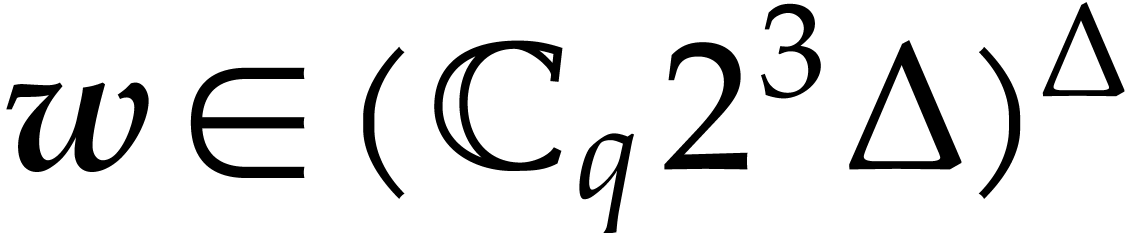

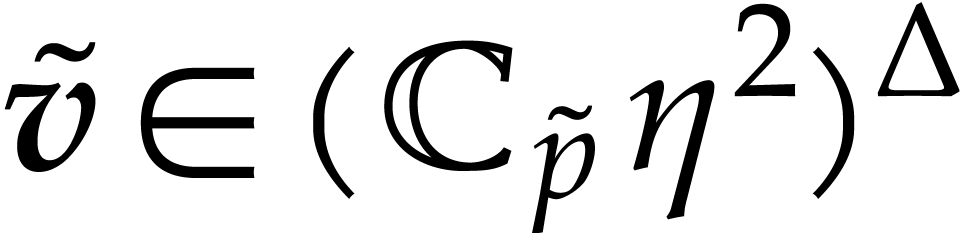

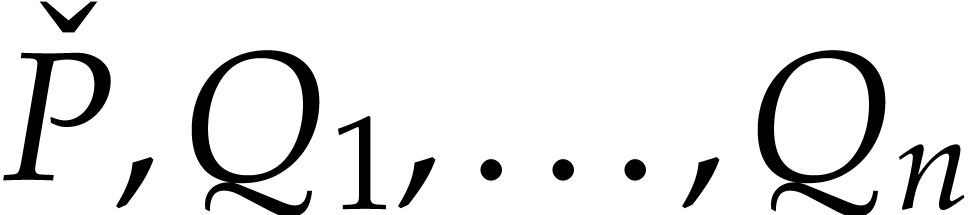

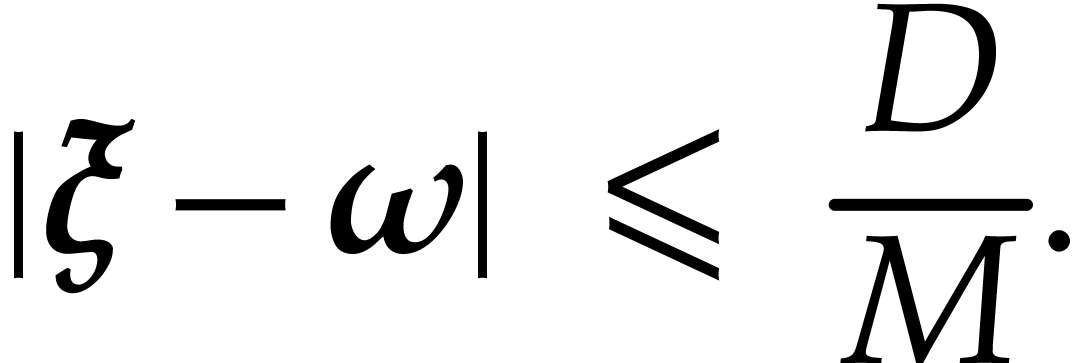

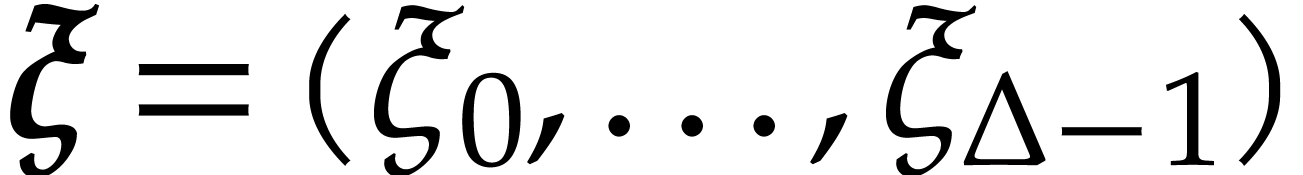

We now turn to the situation where  is a

sufficiently small perturbation of

is a

sufficiently small perturbation of  .

More precisely, we say that

.

More precisely, we say that  is a

spiroid when there exist polynomials

is a

spiroid when there exist polynomials

such that

for all  , and

, and

with the convention that  and

and  . We call

. We call  and

and  the dimension and the degrees of the

spiroid and let

the dimension and the degrees of the

spiroid and let

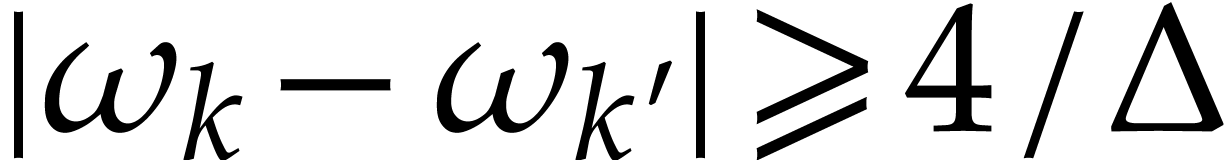

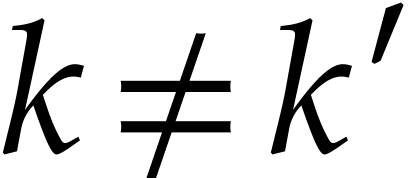

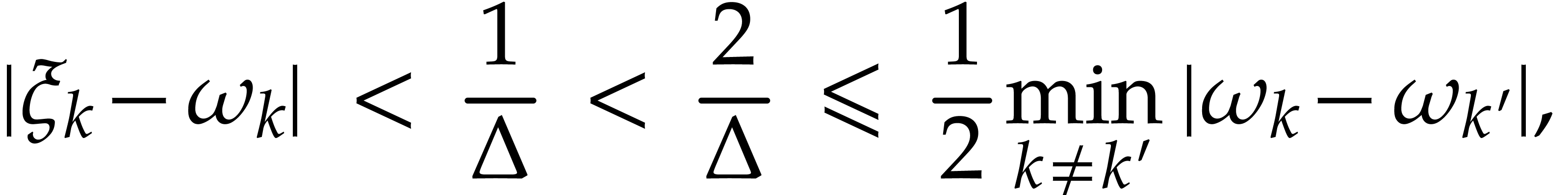

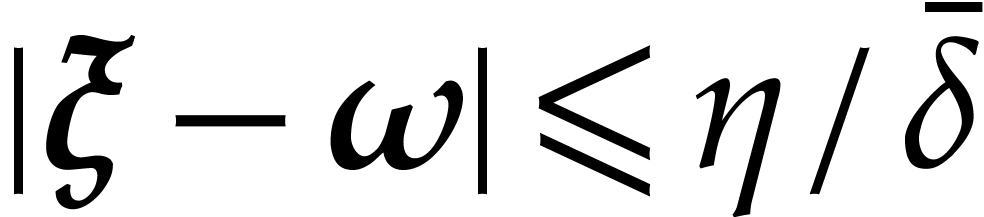

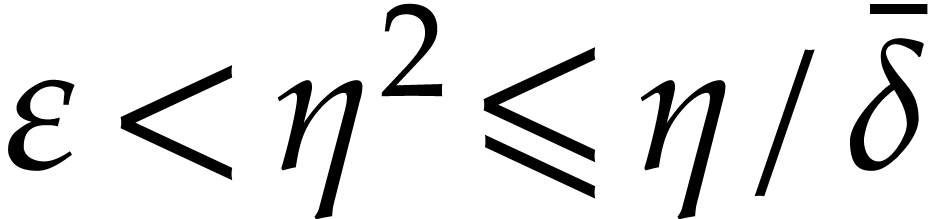

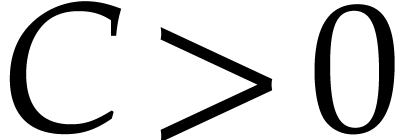

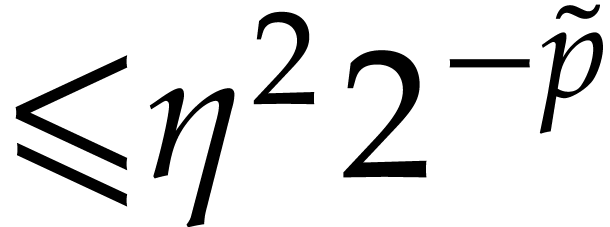

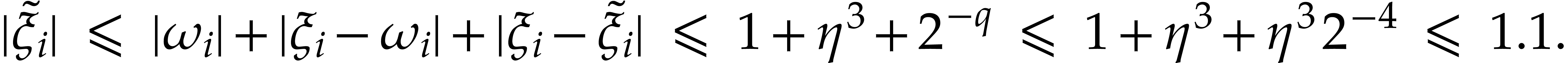

By Lemma 6 we have  for all

for all  . Consequently,

. Consequently,

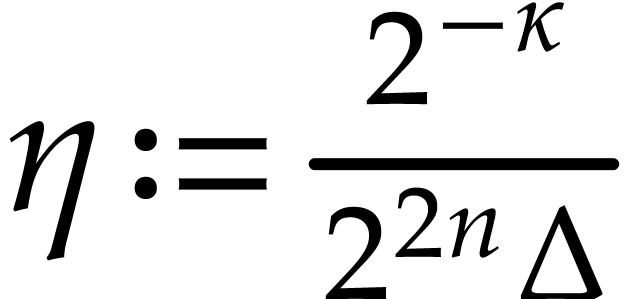

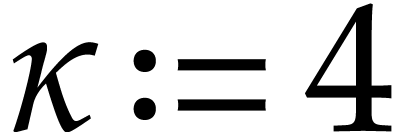

so the points  are pairwise distinct. We let

are pairwise distinct. We let

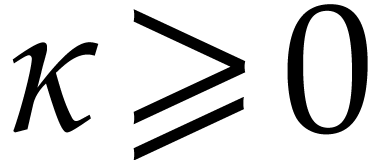

where  is a constant, that will be specified

later. We denote by

is a constant, that will be specified

later. We denote by  an approximation of

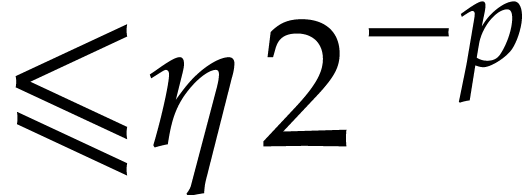

an approximation of  with error

with error  ,

where

,

where  will also be defined later. For

convenience we always take

will also be defined later. For

convenience we always take  .

.

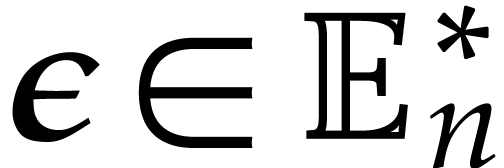

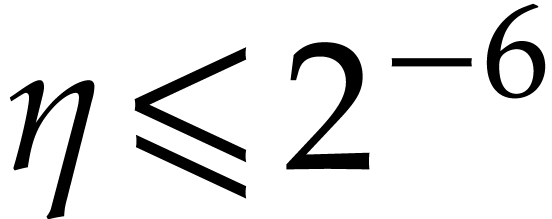

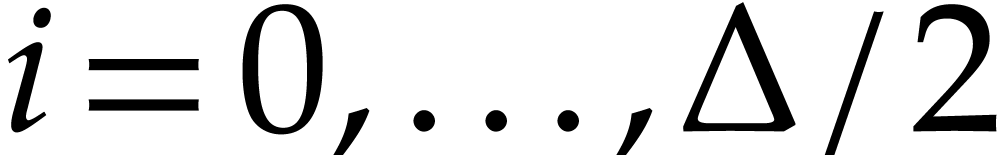

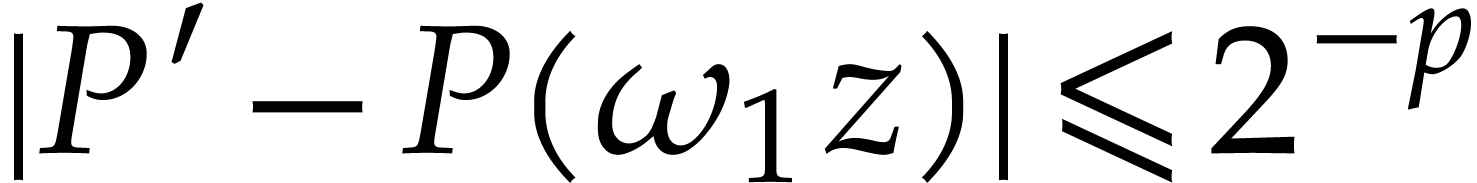

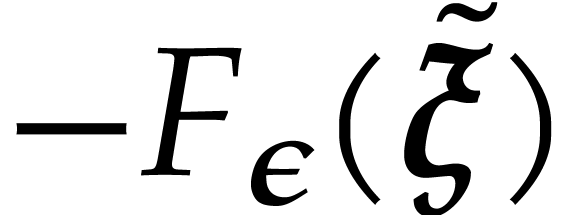

We are to show that  is a spiroid as soon as

is a spiroid as soon as  is sufficiently small.

is sufficiently small.

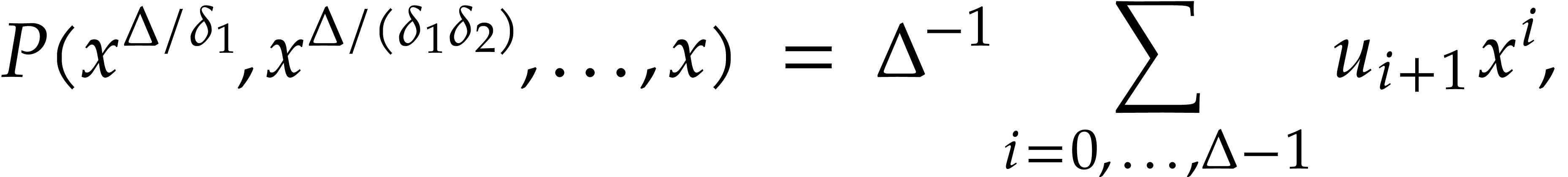

Proof. The polynomial  has degree

has degree

and satisfies  for

for  .

This means that

.

This means that  is the inverse Fourier transform

of

is the inverse Fourier transform

of  , that is

, that is  , following the notation of section 2.2.

We deduce that

, following the notation of section 2.2.

We deduce that  .

.

The two following technical lemmas will be needed several times in the paper.

Proof. We set  for

for  and use the classical inequality

and use the classical inequality

From  , we obtain

, we obtain

Proof. We verify that

,

,  , and let

, and let  be such

that

be such

that  . Given

. Given  , there exists a unique

, there exists a unique  such that

such that  . Moreover,

. Moreover,  .

.

Proof. Let  and define

and define

, where

, where  stands for the unique polynomial in

stands for the unique polynomial in  such that

such that

. From Lemma 10

we know that

. From Lemma 10

we know that  . Using Lemma 11, we deduce

. Using Lemma 11, we deduce

Using Lemma 12 and  ,

we obtain

,

we obtain  , hence

, hence  for

for  .

Consequently,

.

Consequently,  is well defined and we have

is well defined and we have

Finally, we verify that

Proof. From Lemmas 11 and 12, and using

we obtain

Thanks to Lemma 13, there exists  such that

such that  and

and

whence  .

.

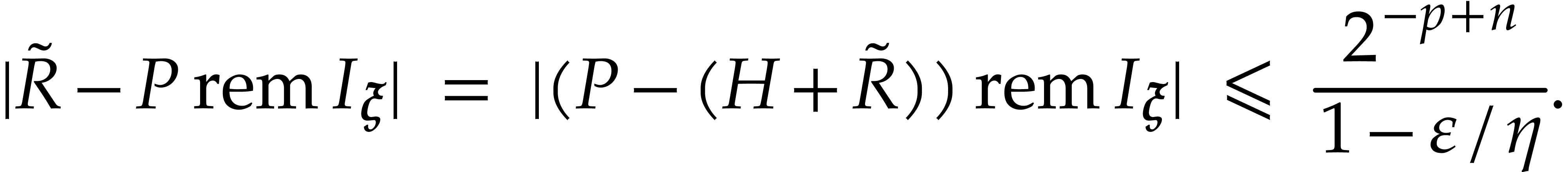

In the rest of this section, we fix  and assume

that

and assume

that  is a spiroid. A family

is a spiroid. A family

is called an extended reduction of  by

the spiroid

by

the spiroid  if

if

Since  , we have

, we have  .

.

Proof. If  then we take

then we take

for all

for all  .

Otherwise, without loss of generality, we may assume that

.

Otherwise, without loss of generality, we may assume that  . For

. For  ,

we construct sequences

,

we construct sequences  ,

,  of polynomials as follows. For

of polynomials as follows. For  , we set

, we set  and

and  for

for  . By

induction, we assume that these sequences are defined up to some index

. By

induction, we assume that these sequences are defined up to some index

for some

for some  .

We let

.

We let

and apply Proposition 9 to  without

any rounding, and let

without

any rounding, and let  be the corresponding

extended reduction with

be the corresponding

extended reduction with  . We

have

. We

have

It follows that

Hence,

In particular  converges to a limit written

converges to a limit written  . For

. For  we

have

we

have

The proof of Proposition 15 can be turned into an algorithm

to compute approximations of extended reductions. For efficiency

reasons,  is required to be sufficiently small.

is required to be sufficiently small.

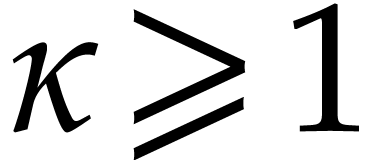

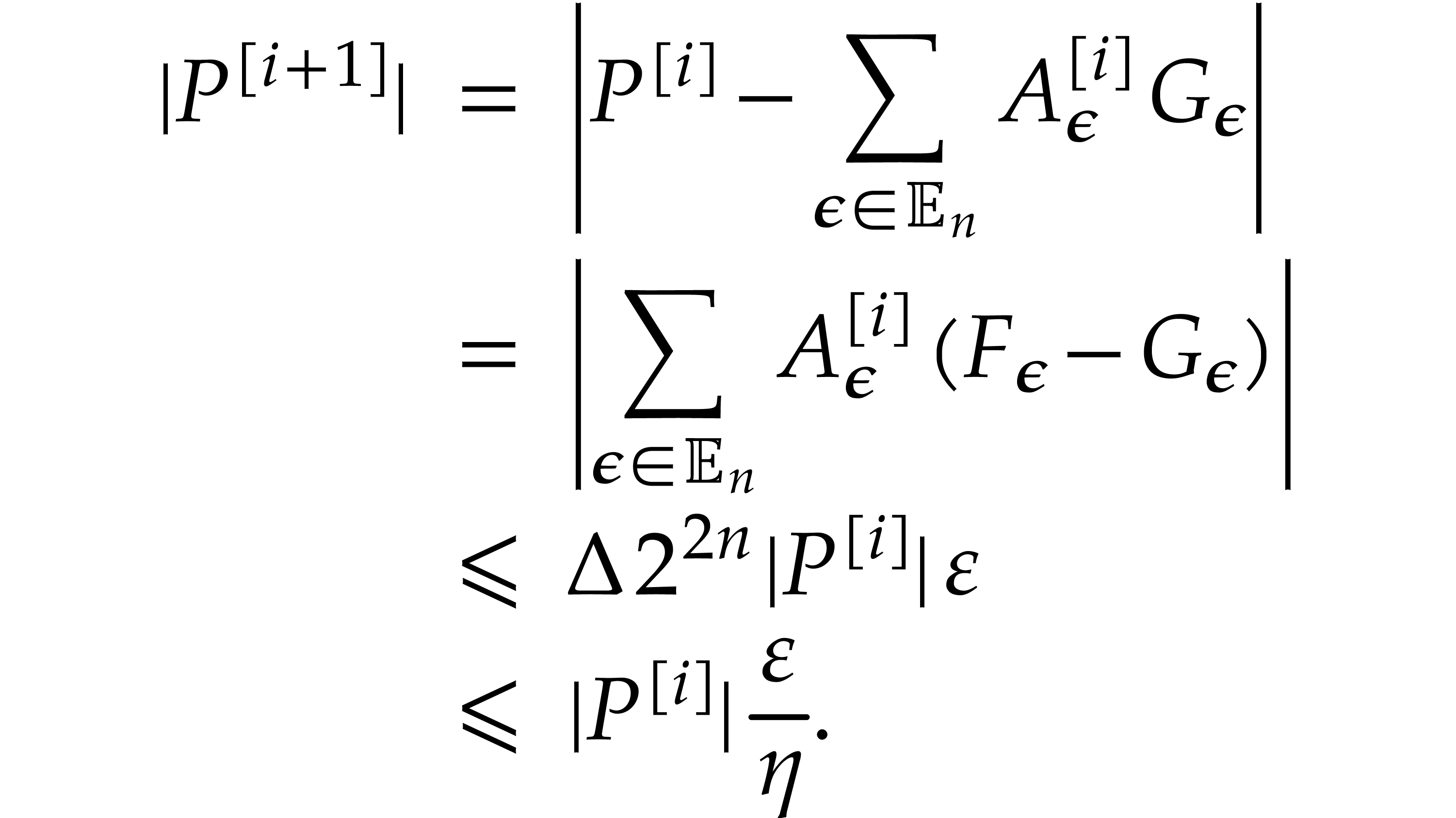

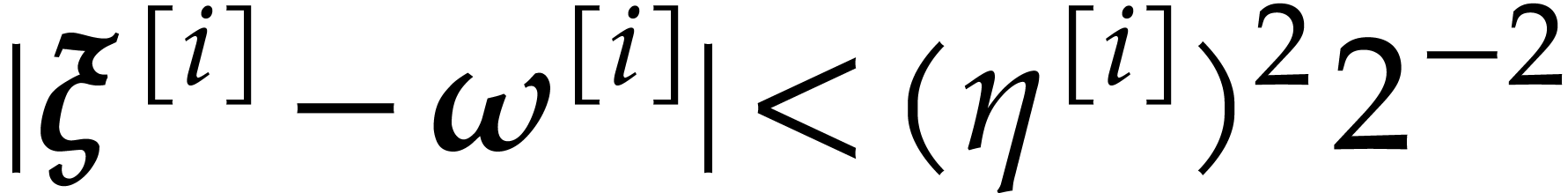

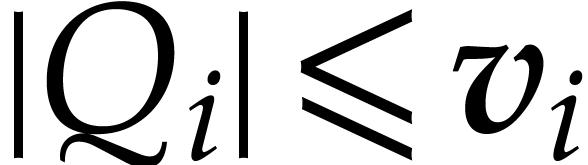

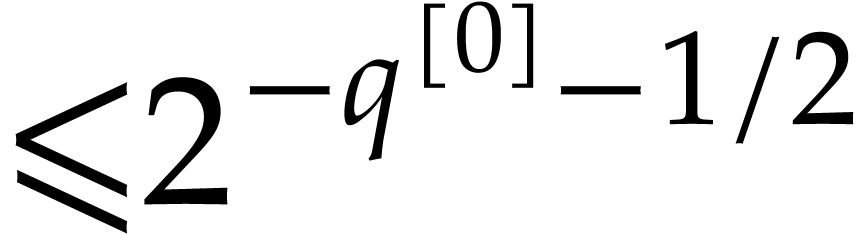

Proof. We adapt the proof of Proposition 15. For  , we

construct sequences

, we

construct sequences  with

with  and

and  as follows.

as follows.

For  , we set

, we set  and

and  for

for  .

By induction, we assume that these sequences have been defined up to

.

By induction, we assume that these sequences have been defined up to

for some

for some  .

We compute

.

We compute

exactly. Note that  . We

further assume by induction that

. We

further assume by induction that  .

Applying Proposition 9 to

.

Applying Proposition 9 to  ,

let

,

let  be the obtained extended reduction. Then

be the obtained extended reduction. Then

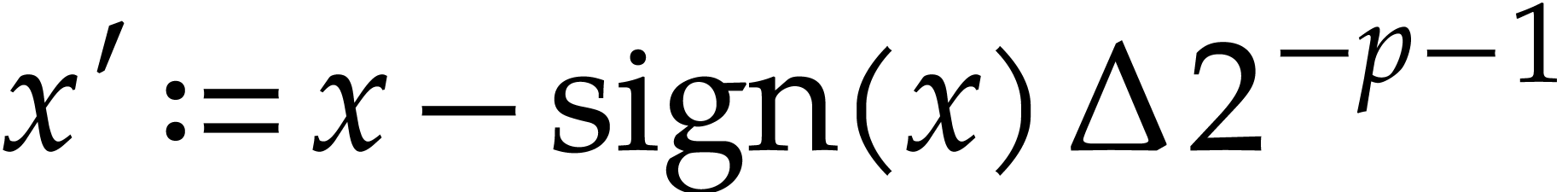

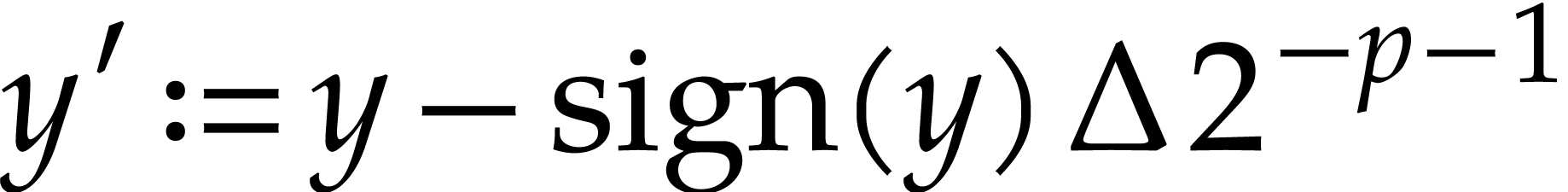

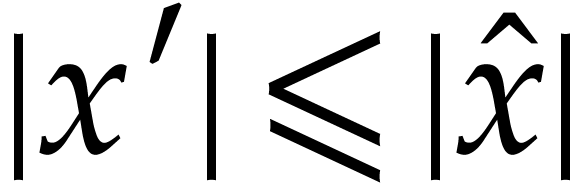

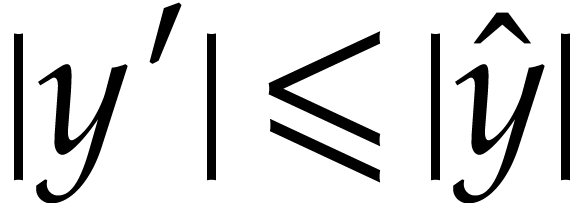

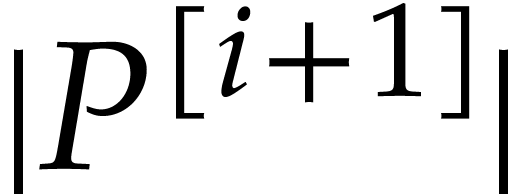

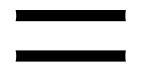

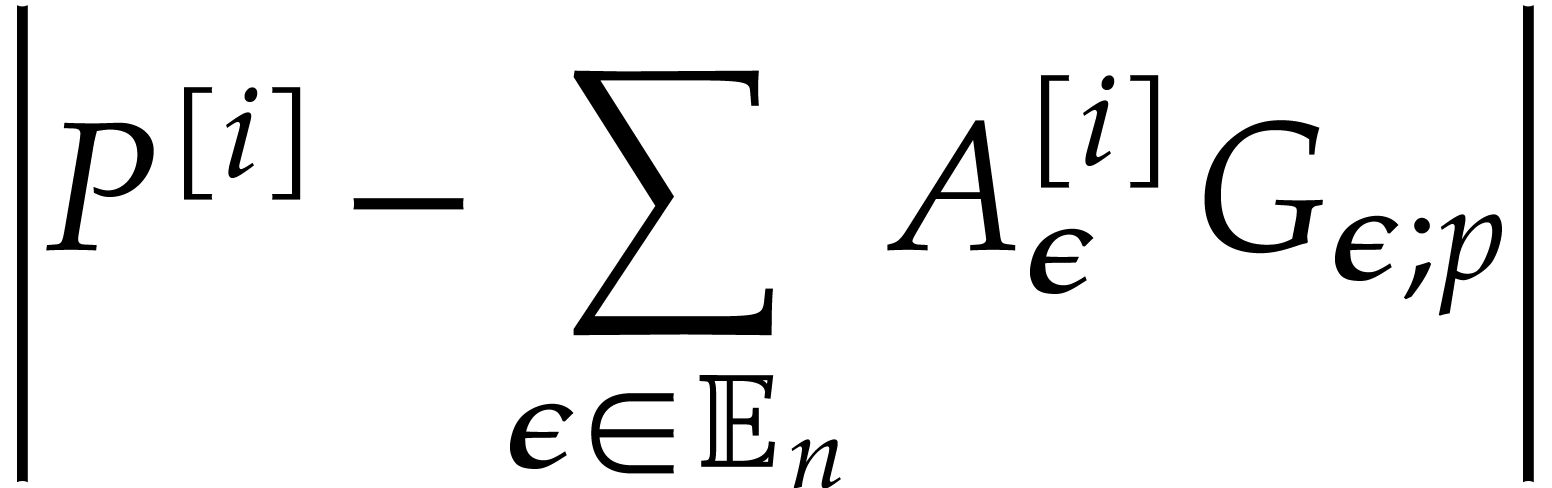

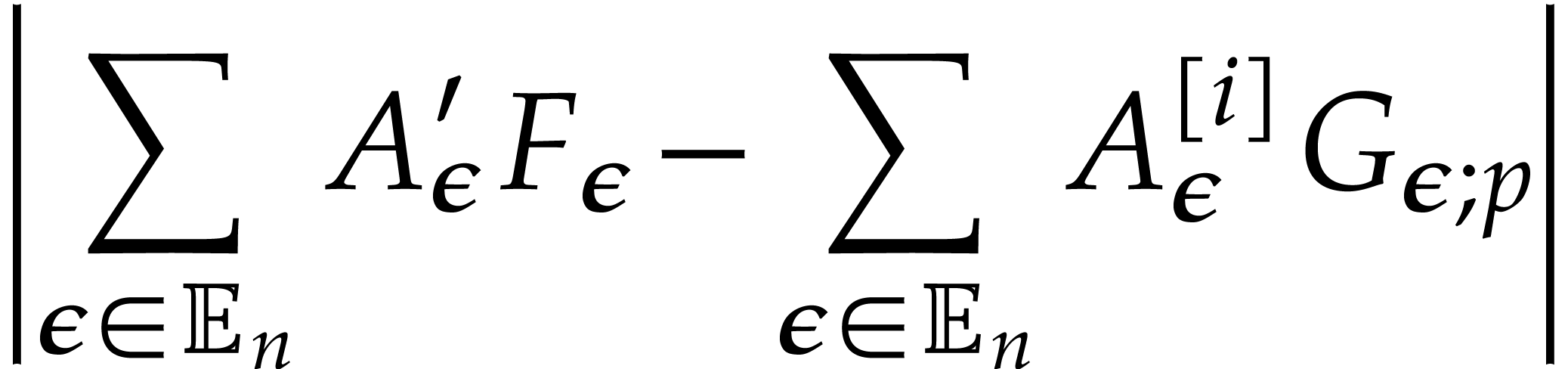

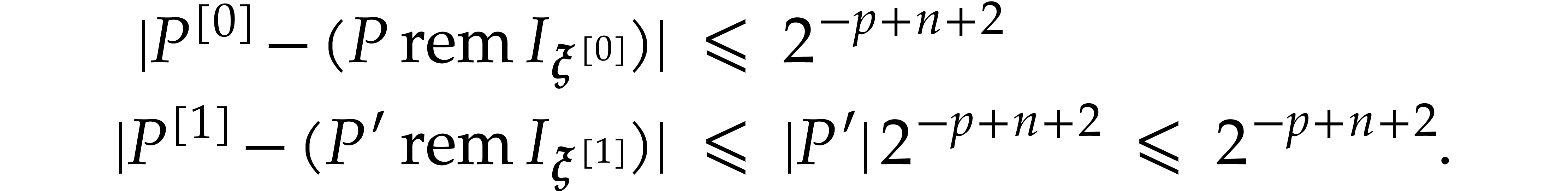

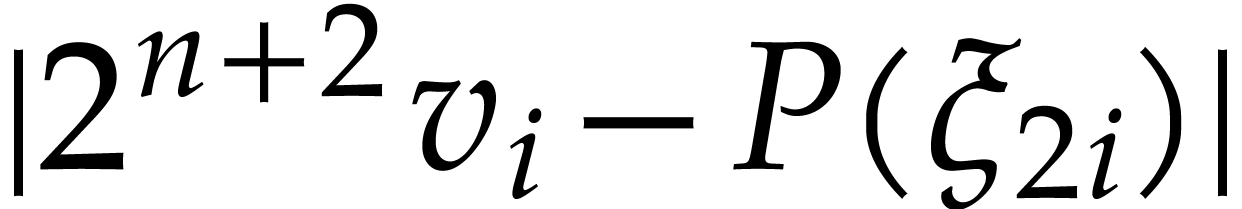

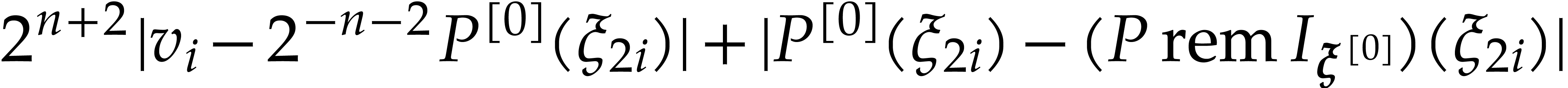

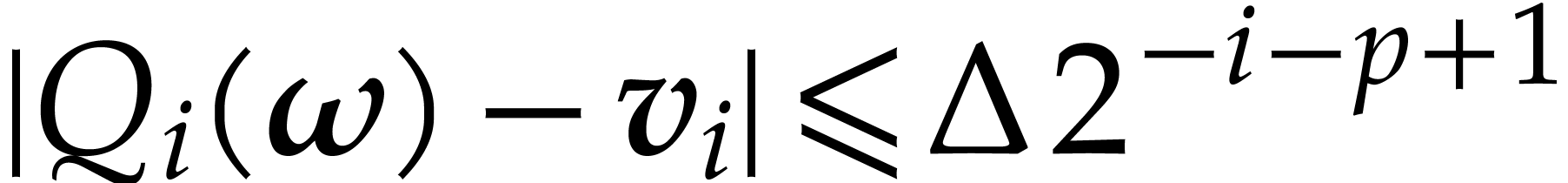

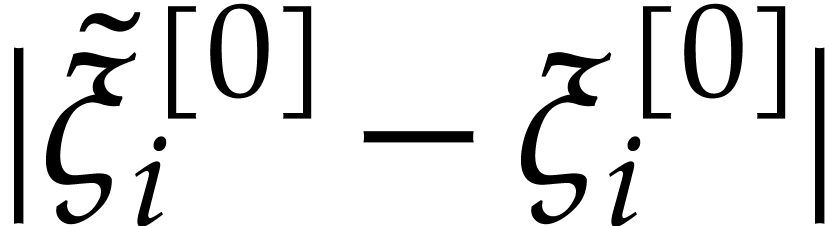

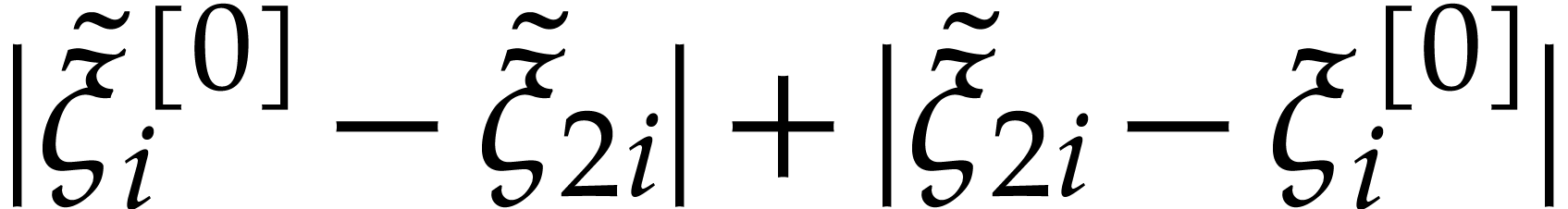

Using Lemma 3, we compute a truncation  of

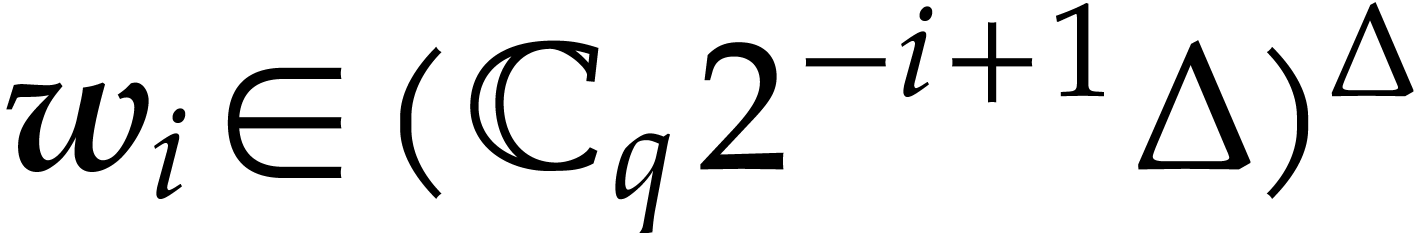

of  in

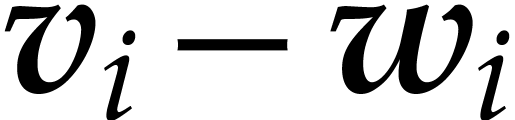

in  with error

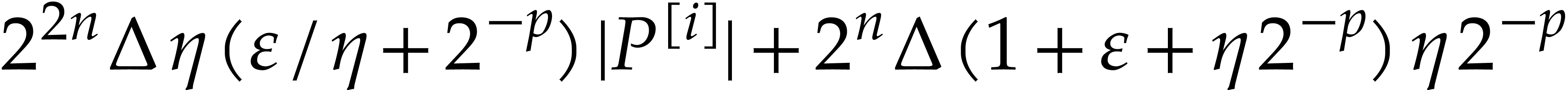

with error  . We obtain

. We obtain

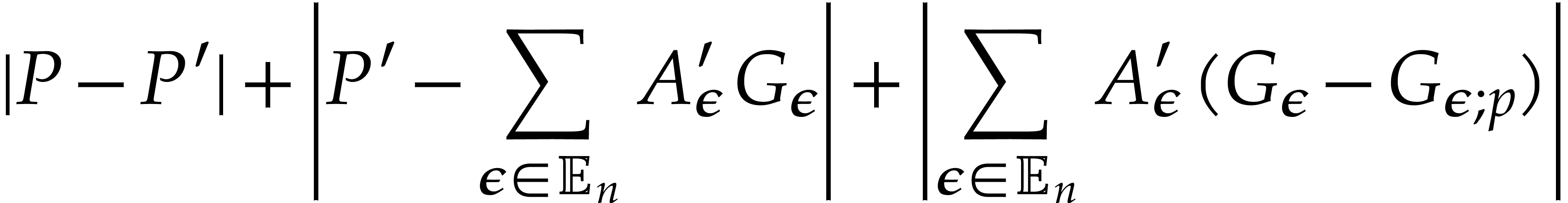

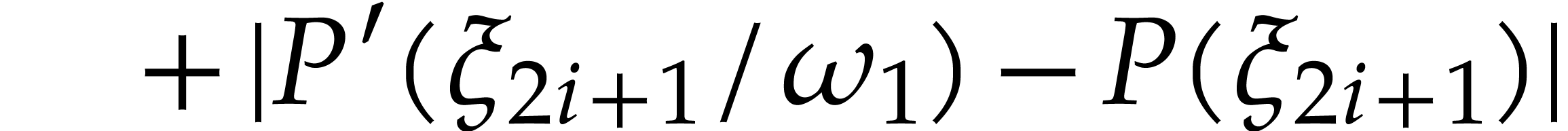

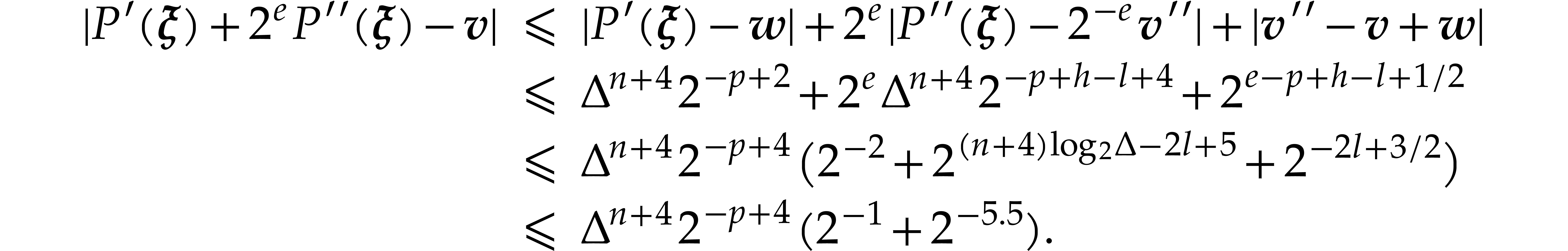

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

(since  ) ) |

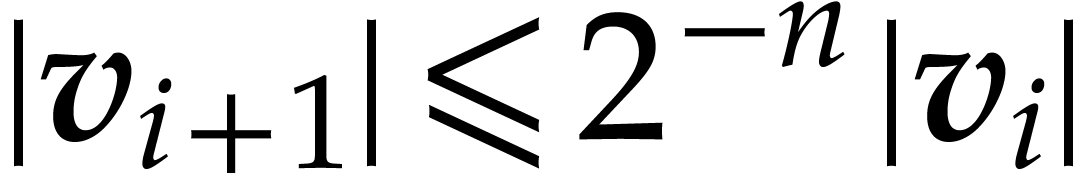

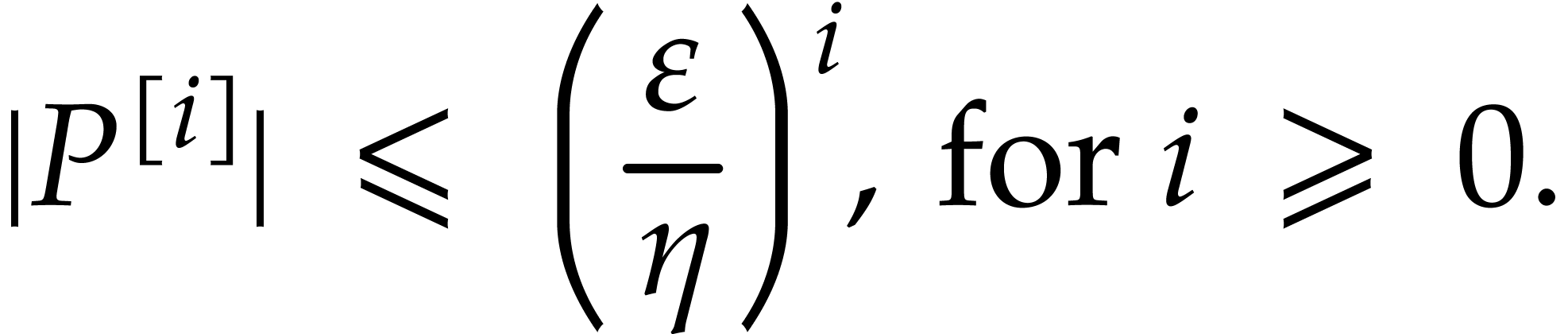

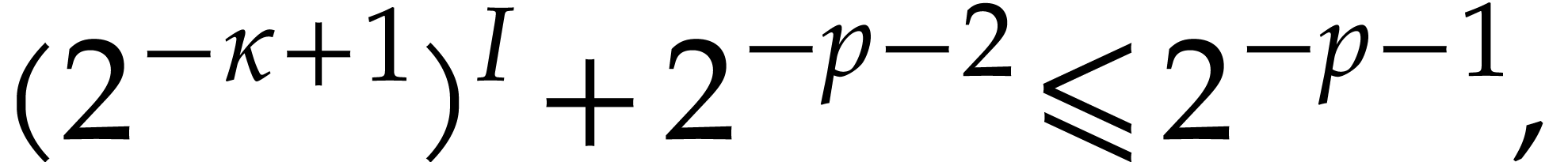

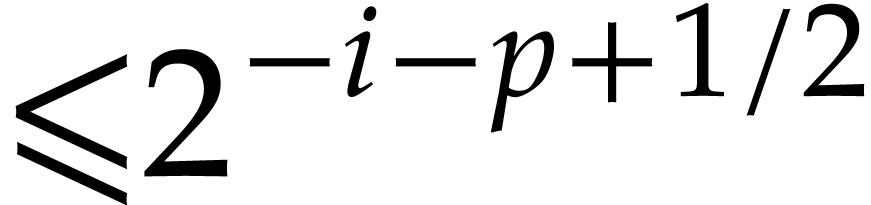

Iterating the latter inequality yields

In particular,  We are done with the construction

of the sequences

We are done with the construction

of the sequences  and

and  . Let

. Let  be the smallest

integer such that

be the smallest

integer such that

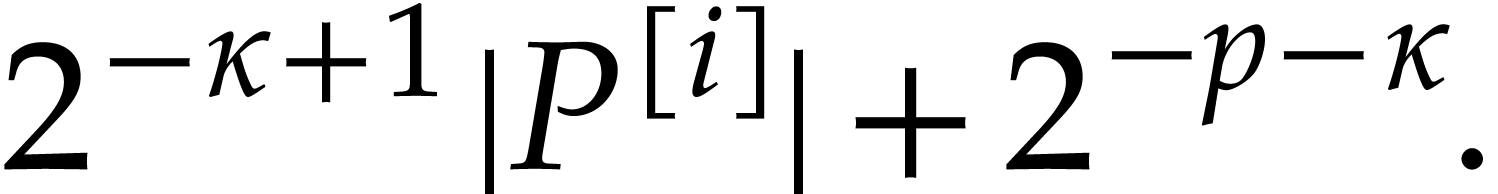

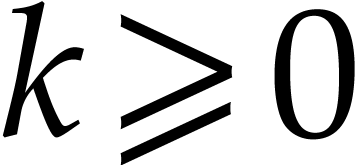

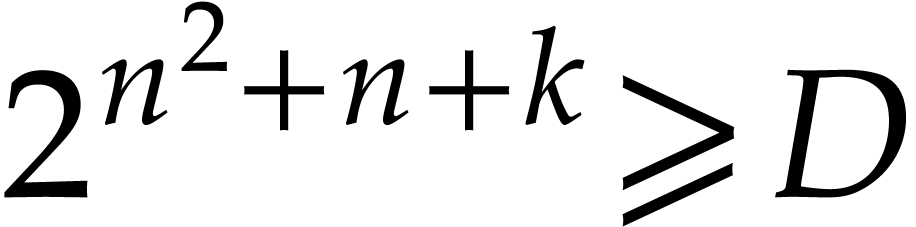

|

(4) |

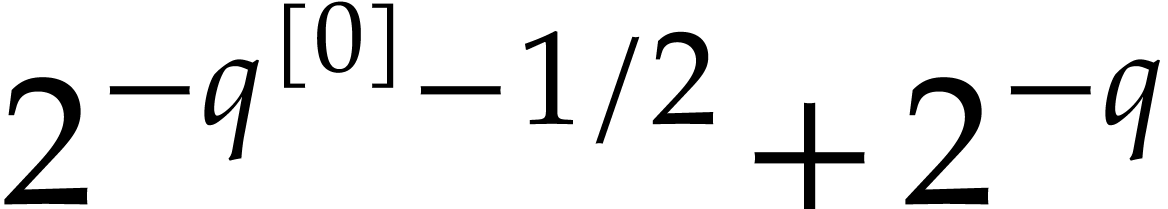

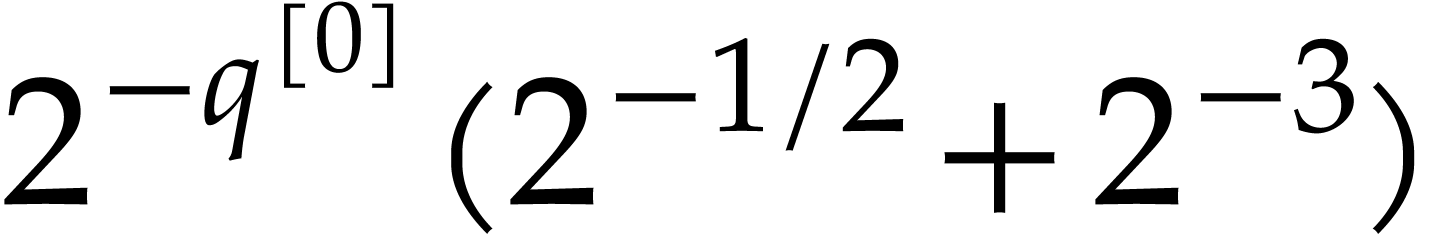

that is

since  . Note that

. Note that

|

(5) |

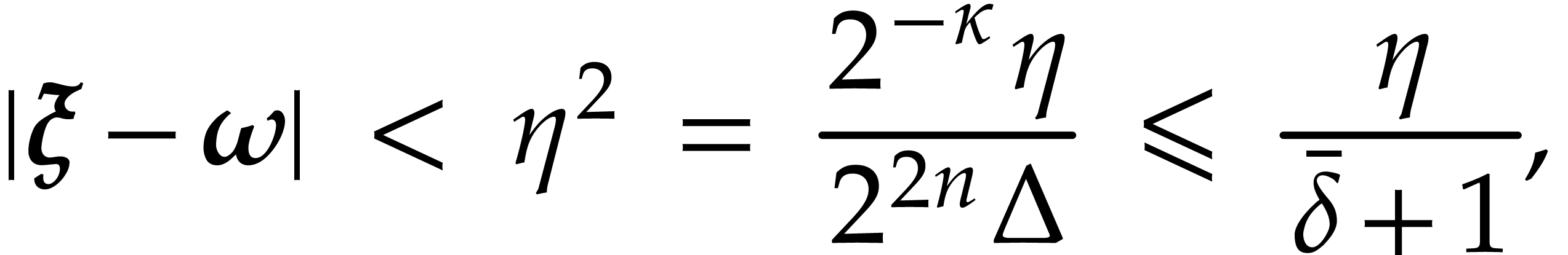

We take  and verify that

and verify that

Finally, we obtain

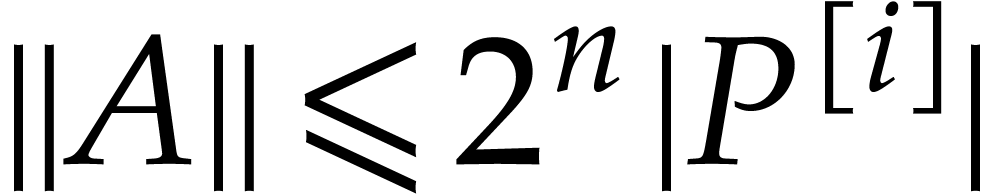

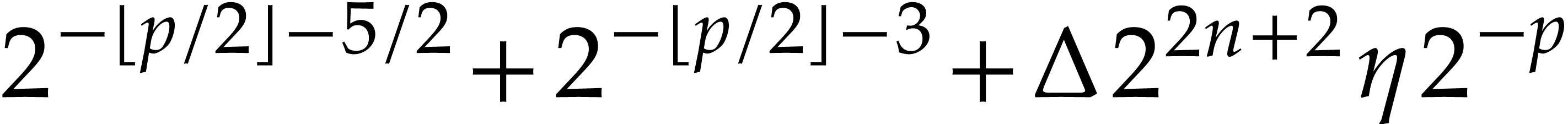

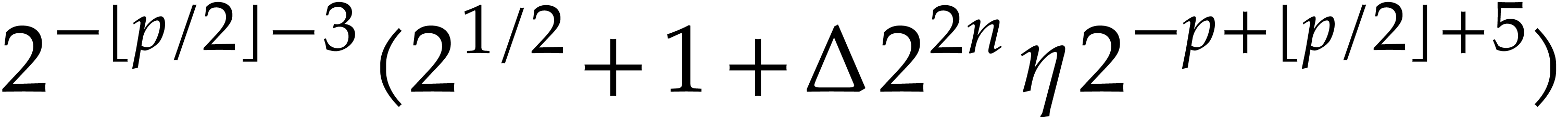

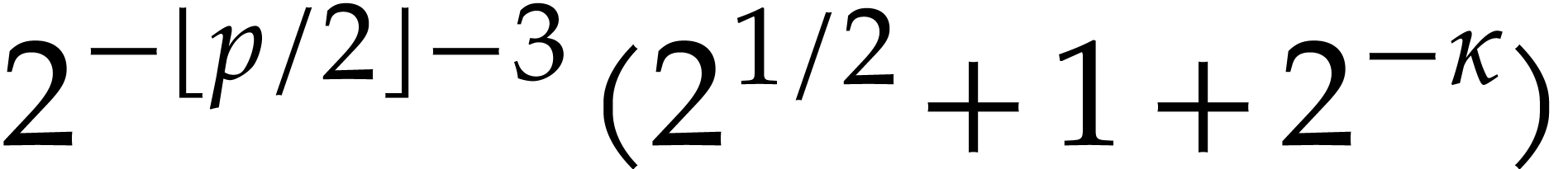

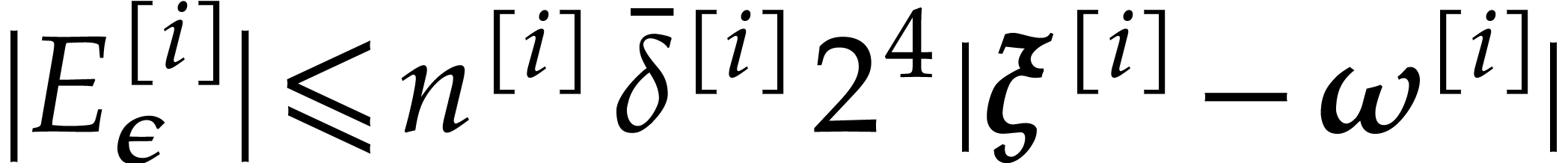

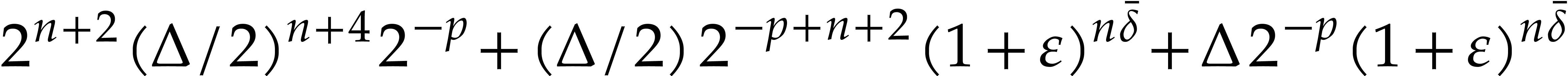

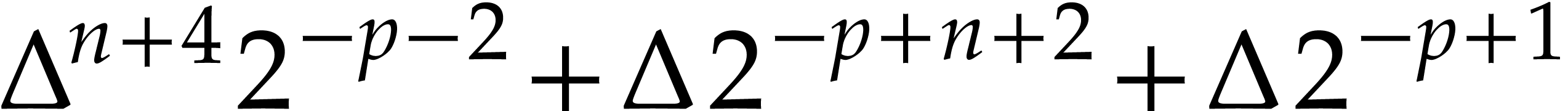

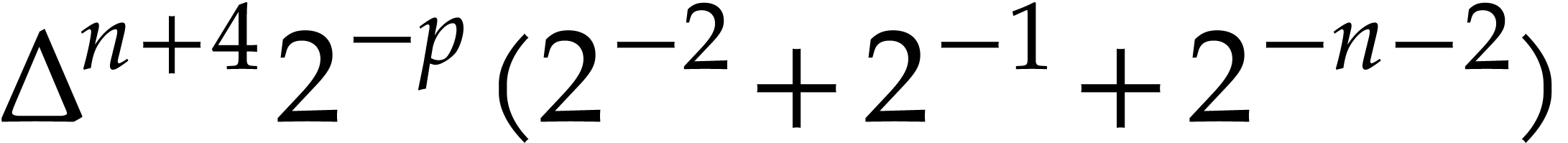

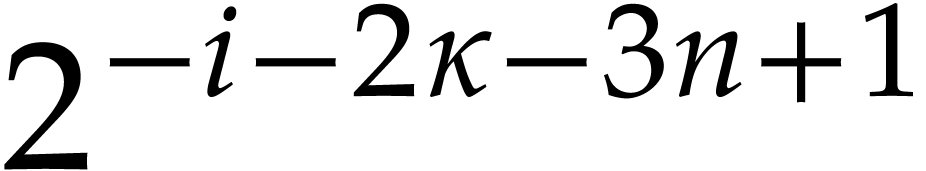

As for the complexity, one product  takes time

takes time

, and

, and  is computed with error

is computed with error  .

Consequently, the computation of

.

Consequently, the computation of  from

from  runs in time

runs in time

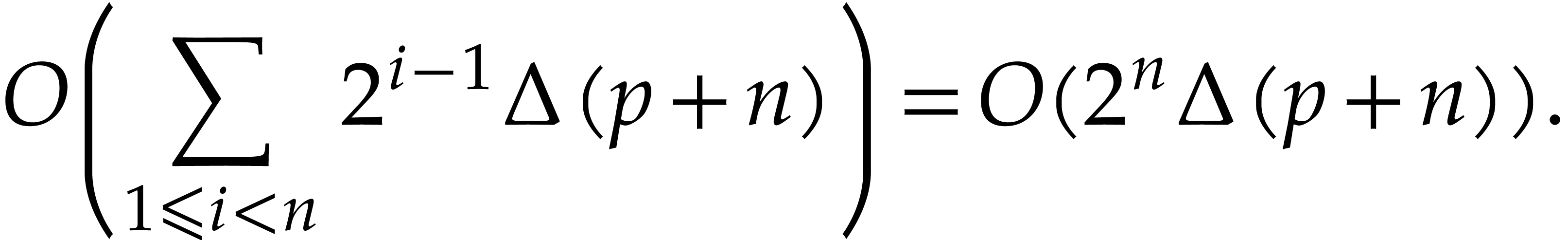

Each use of Proposition 9 contributes  . Since

. Since  ,

the total cost for computing

,

the total cost for computing  and

and  up to index

up to index  is

is  .

.

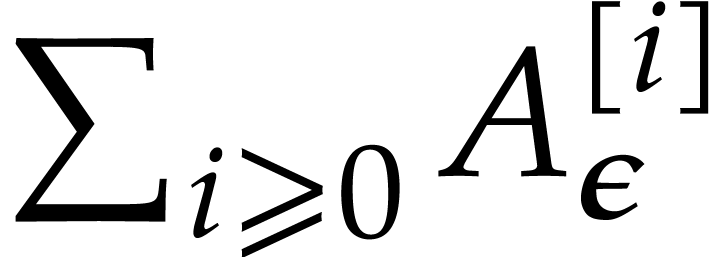

The numerical convergence of the method behind Lemma 16 is linear, which is sufficient for small precisions. For higher precisions, our next faster algorithm benefits from the “divide and conquer” paradigm. In order to upper bound the norms of the extended reductions, we introduce the auxiliary notation

Note that  is nondecreasing in

is nondecreasing in  and that

and that  for all

for all  .

.

Algorithm

If  then return the extended reduction

from Lemma 16.

then return the extended reduction

from Lemma 16.

Compute a truncation  of

of  with error

with error  using Lemma 3.

Apply Algorithm 2 recursively to

using Lemma 3.

Apply Algorithm 2 recursively to  and let

and let  denote the result.

denote the result.

Compute a truncation  of

of

with error  . Apply

Algorithm 2 recursively to

. Apply

Algorithm 2 recursively to  and let

and let  denote the result.

denote the result.

Return a truncation of  with error

with error  , by using Lemma 3.

, by using Lemma 3.

Proof. If  then the

output is correct in step 1 by Lemma 16. Otherwise

then the

output is correct in step 1 by Lemma 16. Otherwise  , so that

, so that  and

and  . Consequently, the

algorithm always terminates. In step 2, by induction, we have

. Consequently, the

algorithm always terminates. In step 2, by induction, we have

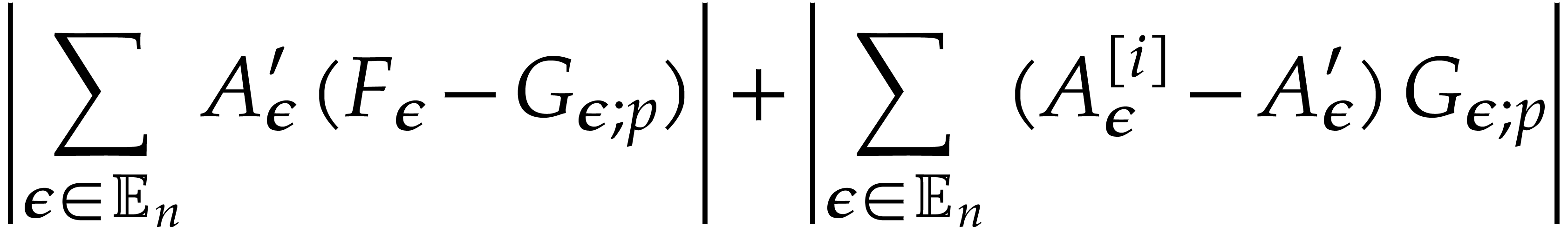

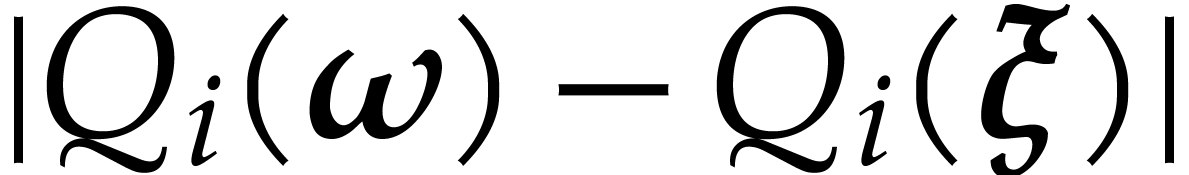

We verify that

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

(since  ) ) |

|

|

|

(since  ) ) |

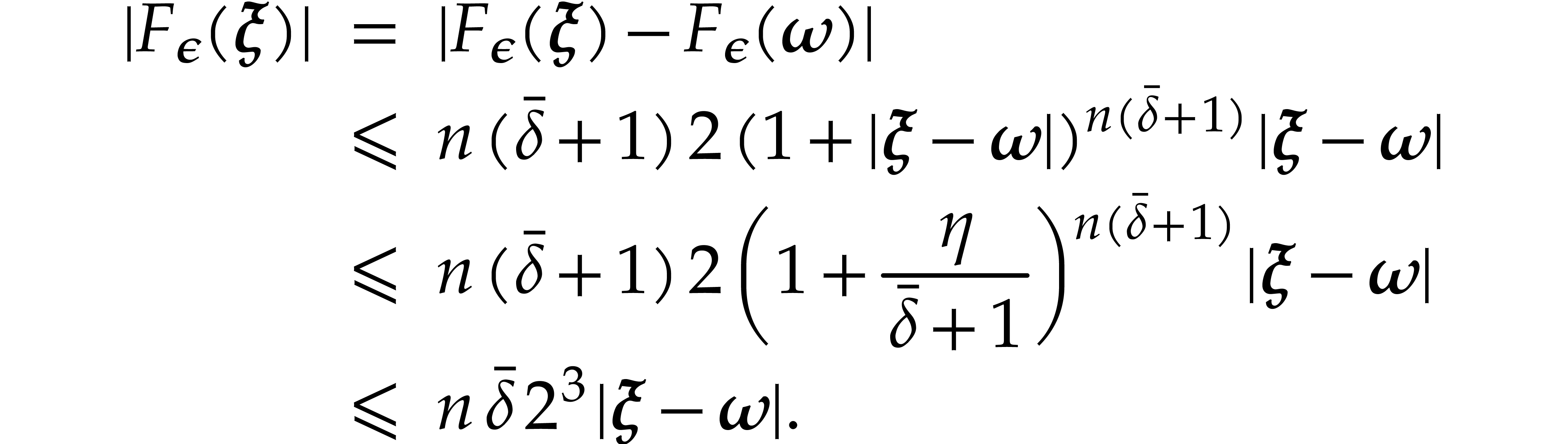

so the polynomial  is well defined in step 3, and

we have

is well defined in step 3, and

we have

Let  be a truncation of

be a truncation of  with error

with error  . On the one hand,

. On the one hand,

On the other hand, we obtain

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

(since  ) ) |

which yields

|

(8) |

Combining

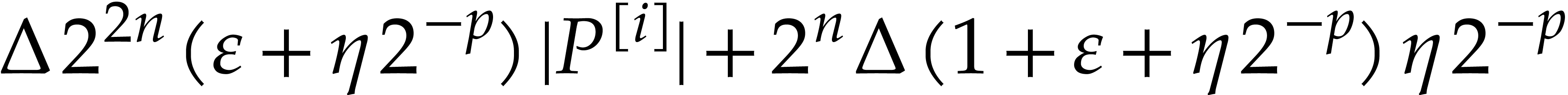

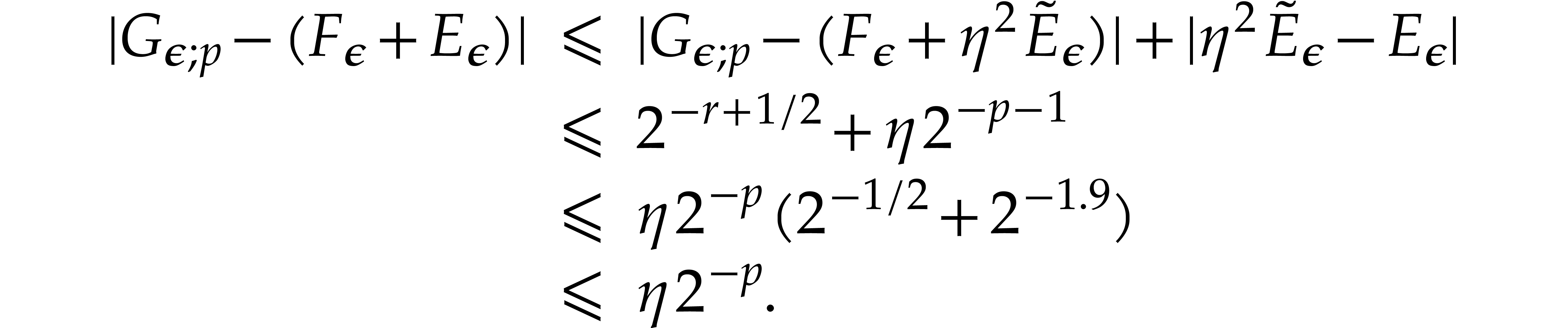

This concludes the proof of the correctness of the algorithm. Let us now analyze the complexity. By Lemma 16, step 1 contributes

Each product  can be computed in time

can be computed in time

The total cost to obtain  is therefore bounded by

is therefore bounded by

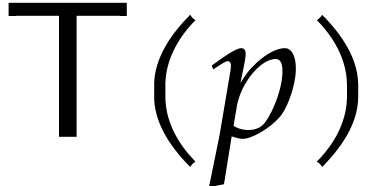

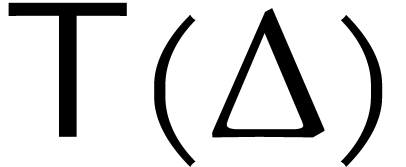

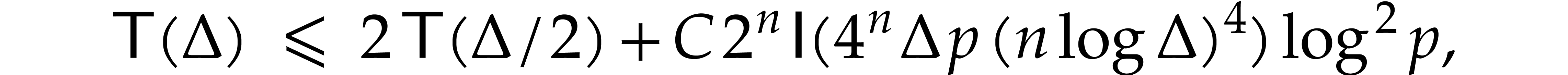

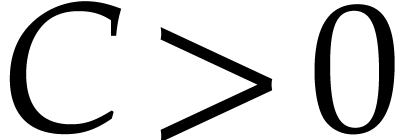

Let  be the computation time as a function of

be the computation time as a function of

. So far, we have shown that

. So far, we have shown that

for  . Unrolling this

inequality leads to

. Unrolling this

inequality leads to

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

The following corollary is the main result of this section.

Proof. Proposition 17 allows us to compute

such that  for some

for some  .

Using Proposition 15, we deduce that

.

Using Proposition 15, we deduce that

Using Lemma 2, we finally compute an approximation of  in

in  with error

with error  and verify that

and verify that

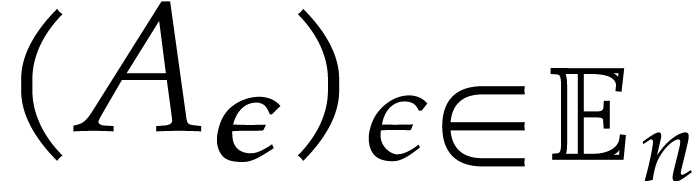

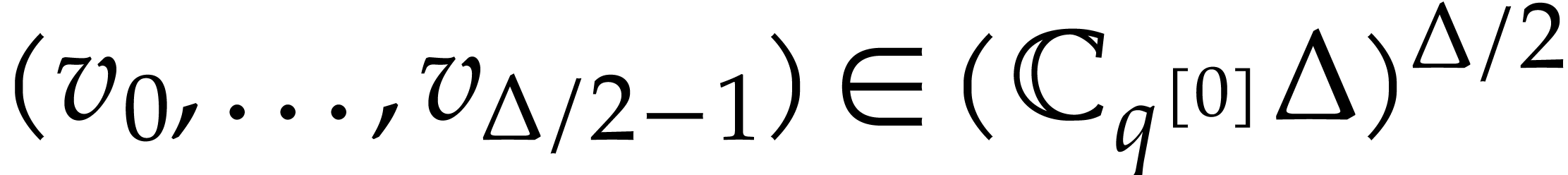

This section is devoted to multi-point evaluation and interpolation at a spiroid. Evaluation will follow the classical “divide and conquer” paradigm with respect to the number of evaluation points. Interpolation will reduce to evaluation.

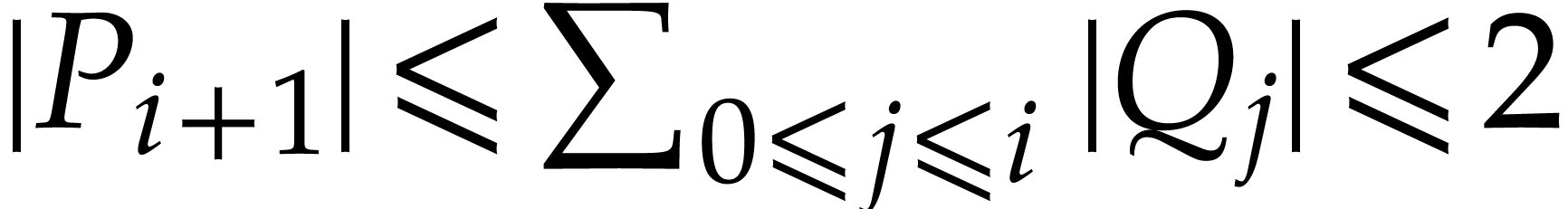

Let  be as in the previous section. If

be as in the previous section. If  for some

for some  , then

, then

Without loss of generality, this allows us to replace  by

by  of dimension

of dimension  with

with

for each

for each  .

In what follows, we will only work with spiroids

.

In what follows, we will only work with spiroids  for which

for which  whenever

whenever  .

.

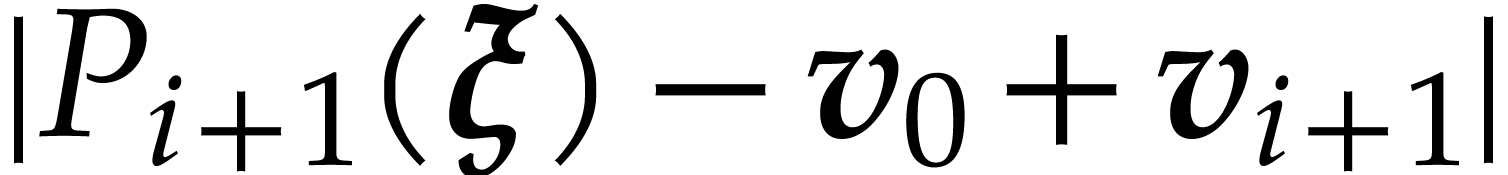

Our algorithm for multi-point evaluation of a polynomial  at

at  is based on a generalization of

the classical remainder tree technique used for the univariate case [5, Chapter 10]. If

is based on a generalization of

the classical remainder tree technique used for the univariate case [5, Chapter 10]. If  ,

then an evaluation tree for

,

then an evaluation tree for  consists of

a single leaf labeled by

consists of

a single leaf labeled by  . If

. If

and

and  ,

then

,

then  induces two sequences of points

induces two sequences of points  which are defined by

which are defined by

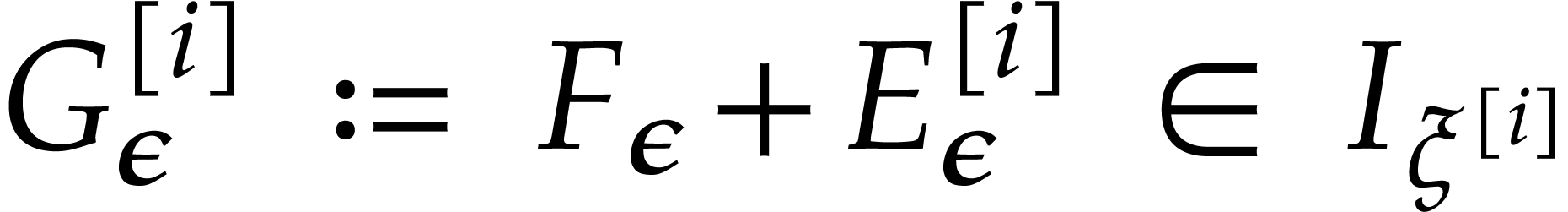

For  , we write

, we write  for the dimension of

for the dimension of  ,

,

for its partial degrees, and

for its partial degrees, and  for its degree. The perturbations of the defining polynomials of

for its degree. The perturbations of the defining polynomials of  are written

are written  ,

so we have

,

so we have

for all  . We further define

. We further define

Note that  ,

,  , and

, and  , for

, for  .

.

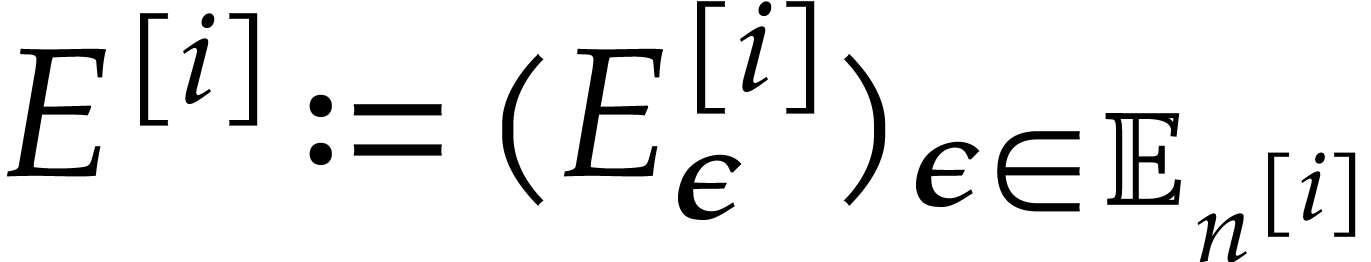

An evaluation tree for the spiroid  consists of a root that is labeled by the family

consists of a root that is labeled by the family  and two children which are recursively the evaluation trees for

and two children which are recursively the evaluation trees for  and

and  .

Since

.

Since  , if

, if  then

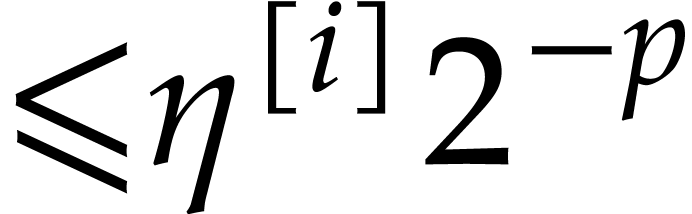

then  . So, Proposition 14 ensures that the

. So, Proposition 14 ensures that the  exists with

exists with  , whenever

, whenever  . This shows that evaluation trees exist whenever

. This shows that evaluation trees exist whenever

is sufficiently small. The construction of these

trees is postponed to the end of this section.

is sufficiently small. The construction of these

trees is postponed to the end of this section.

An evaluation tree for  is said to be known

with error

is said to be known

with error  if

if  is given with error

is given with error  , and if

the evaluation tree for

, and if

the evaluation tree for  is known with error

is known with error  for

for  . We

will see in section 4.3 that for such an evaluation tree

with error

. We

will see in section 4.3 that for such an evaluation tree

with error  , the

, the  will be elements of

will be elements of  with

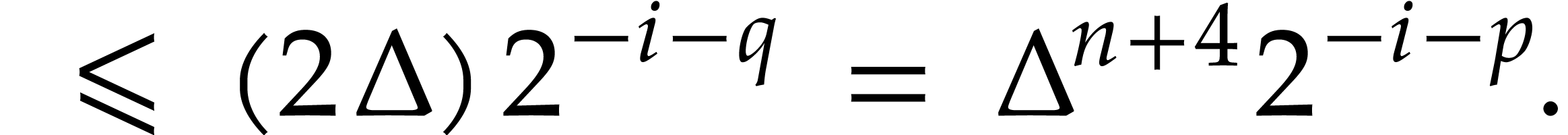

with  . Our next algorithm performs fast

evaluation at

. Our next algorithm performs fast

evaluation at  by taking advantage of evaluation

trees.

by taking advantage of evaluation

trees.

Algorithm

If  then return an approximation of

then return an approximation of  in

in  with error

with error  , by using Lemma 2.

, by using Lemma 2.

Compute a truncation  of

of  with error

with error  .

.

Compute truncations  and

and  of

of  and

and  in

in  with error

with error  via

Corollary 18.

via

Corollary 18.

Apply Algorithm 3 recursively to  and the evaluation sub-trees for

and the evaluation sub-trees for  in

order to obtain approximations

in

order to obtain approximations  of

of  with error

with error  ,

where

,

where  .

.

Apply Algorithm 3 recursively to  and the evaluation sub-trees for

and the evaluation sub-trees for  in

order to obtain an approximation

in

order to obtain an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  ,

where

,

where  .

.

Return an approximation of  in

in  with error

with error  .

.

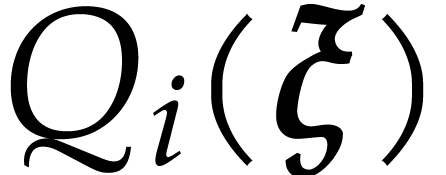

Proof. If  then the

algorithm behaves as expected. Let us now assume that

then the

algorithm behaves as expected. Let us now assume that  . The correctness mostly relies on the

identities

. The correctness mostly relies on the

identities

for  . Let us verify that

computations are done with sufficiently large precisions. By

construction, we have

. Let us verify that

computations are done with sufficiently large precisions. By

construction, we have  and

and  . Corollary 18 yields

. Corollary 18 yields  ,

,  and

and

Since  , Lemma 12

ensures that

, Lemma 12

ensures that

|

(9) |

In particular, it follows that  .

Assuming by induction that the claimed properties hold for the recursive

call in step 4, we obtain

.

Assuming by induction that the claimed properties hold for the recursive

call in step 4, we obtain

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

(since  ) ) |

|

|

|

Similarly, for  we obtain

we obtain

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

(since  ) ) |

|

|

|

We are done with the correctness. As for the complexity analysis, the

computation of  and then of

and then of  , with

, with  bits of

precision in step 2 can be done in time

bits of

precision in step 2 can be done in time  by Lemma

4, under the assumption

by Lemma

4, under the assumption  .

Therefore, step 2 runs in time

.

Therefore, step 2 runs in time  .

In view of Corollary 18, the complexity

.

In view of Corollary 18, the complexity  of Algorithm 3 satisfies

of Algorithm 3 satisfies

for some universal constant  .

Unrolling this inequality, we obtain

.

Unrolling this inequality, we obtain

Unrolling this new inequality, while using the geometric increase of

, we obtain the desired

complexity bound.

, we obtain the desired

complexity bound.

Our interpolation algorithms rely on the evaluation one. We begin with a method dedicated to small precisions.

Proof. Using Lemma 5, we compute

such that

such that

|

(10) |

and  in time

in time  .

For

.

For  we take the unique polynomial of

we take the unique polynomial of  such that

such that

so we have  . Finally

. Finally

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

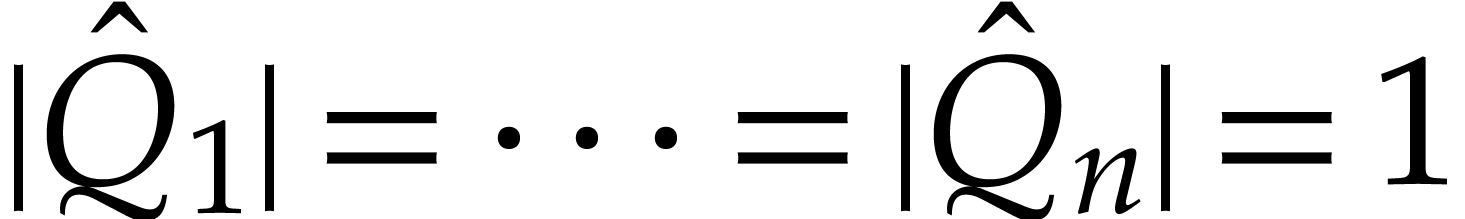

,

,  , and

, and  .

Given an evaluation tree for

.

Given an evaluation tree for  with error

with error  for

for  ,

and

,

and  , we can compute

, we can compute  such that

such that

in time  .

.

Proof. Let  .

By induction, we construct sequences

.

By induction, we construct sequences  and

and  such that

such that  and

and  . We set

. We set  and

and  . For

. For  ,

we first compute

,

we first compute  as the polynomial interpolated

from

as the polynomial interpolated

from  by inverse FFT as in Lemma 20,

so we have

by inverse FFT as in Lemma 20,

so we have  and

and  .

Using Algorithm 3, we then compute an approximation

.

Using Algorithm 3, we then compute an approximation  of

of  with error

with error

Using Lemma 3, we next compute a truncation  of

of  with error

with error  . Then

. Then

Using Lemmas 11 and 12, we obtain

|

|

|

|

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

It follows that

so the sequence  converges to

converges to  . We define

. We define  and verify

that

and verify

that

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

||

|

|

On the other hand, we have  .

We take

.

We take  minimal such that

minimal such that

so we have  . Let

. Let  be a truncation of

be a truncation of  with error

with error

. Then

. Then

Finally, Lemma 20 asserts that each  can be computed in time

can be computed in time  . By

Proposition 19, each

. By

Proposition 19, each  is obtained in

time

is obtained in

time  .

.

The next faster algorithm exploits the usual “divide and

conquer” paradigm for large precisions  .

.

Algorithm

If  then compute

then compute  such that

such that  via Lemma 21.

Return an approximation

via Lemma 21.

Return an approximation  of

of  in

in  with error

with error  , by using Lemma 2.

, by using Lemma 2.

Let  and

and  and let

and let

be a truncation of

be a truncation of  in

in  with error

with error  . Apply Algorithm 4 recursively

to

. Apply Algorithm 4 recursively

to  and let

and let  denote the output.

denote the output.

Compute an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  ,

by applying Algorithm 3 to

,

by applying Algorithm 3 to  , where

, where

Let  and compute a truncation

and compute a truncation  of

of  with error

with error  . Apply Algorithm 4

recursively to

. Apply Algorithm 4

recursively to  and let

and let  denote the output.

denote the output.

Return an approximation of  with error

with error

.

.

Proof. If  ,

then

,

then  , whence

, whence  , which implies the termination of the

algorithm. In step 1 we obtain

, which implies the termination of the

algorithm. In step 1 we obtain

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

(since  and and  ) ) |

|

|

|

so the output is correct when the algorithm exits at step 1. After step 3 we have

In step 4, we note that

|

(16) |

and deduce

Therefore, the recursive call in step 4 is valid and gives

|

(17) |

Combining

Consequently,

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

(since  ) ) |

|

|

|

Step 1 takes time

by Lemma 21. Steps 3 runs in time

by Proposition 19. When  ,

the complexity

,

the complexity  of our algorithm therefore

satisfies

of our algorithm therefore

satisfies

for some universal constant  .

Unrolling this inequality, we obtain

.

Unrolling this inequality, we obtain

which concludes the proof.

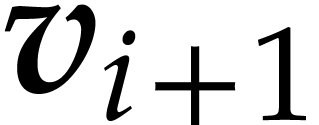

The evaluation tree for  is obtained by

induction: we recursively compute evaluation trees for

is obtained by

induction: we recursively compute evaluation trees for  and

and  , and deduce the one for

, and deduce the one for

as follows.

as follows.

Algorithm

If  then return

then return  and an approximation

and an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  .

.

Let  . For

. For  , let

, let  and compute

and compute  with error

with error  . Recursively compute the evaluation

trees

. Recursively compute the evaluation

trees  for

for  with

error

with

error  .

.

For each  do:

do:

Compute an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  .

.

Apply Algorithm 4 to  ,

,  ,

,

; let

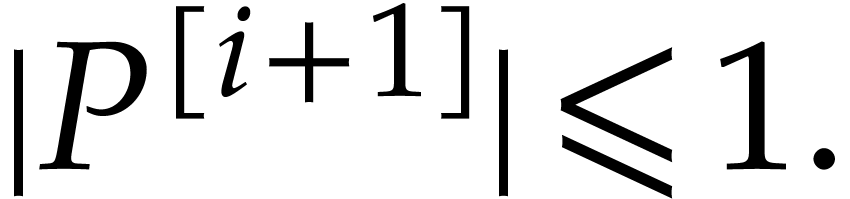

; let  be the returned polynomial, such that

be the returned polynomial, such that  .

.

Compute an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  ,

where

,

where  .

.

Set  and return

and return  , and approximations of

, and approximations of  ,

,  with errors

with errors

and

and  .

.

Proof. If the algorithm exits in step 1, then we

have  , so the output is

correct. Now, let us assume that

, so the output is

correct. Now, let us assume that  and note that

and note that

and

|

(19) |

For  , we compute

, we compute  as the truncation of

as the truncation of  with error

with error

using Lemma 2. Hence,

using Lemma 2. Hence,

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

|

|

|

From Lemma 4, we may compute a truncation  of

of  with error

with error  in time

in time

, provided that

, provided that  . We compute an approximation

. We compute an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  .

It follows that

.

It follows that

Using Lemma 2, we obtain  as the

truncation of

as the

truncation of  with error

with error  . Hence,

. Hence,

For step 3.a, we need to verify that

so the use of Algorithm 4 is valid in step 3.b. Thanks to

Proposition 22 and using that  ,

we obtain

,

we obtain

Lemma 13 yields  .

It follows that

.

It follows that

This concludes the correctness proof. As for the complexity we note that

whenever

whenever  .

In step 3,

.

In step 3,  can be computed in time

can be computed in time  , using binary powering. In step 3.b, the

interpolation of

, using binary powering. In step 3.b, the

interpolation of  takes

takes

operations, by Proposition 22. Overall the complexity  of our algorithm satisfies

of our algorithm satisfies

for some universal constant  .

Unrolling this inequality yields the claimed complexity bound.

.

Unrolling this inequality yields the claimed complexity bound.

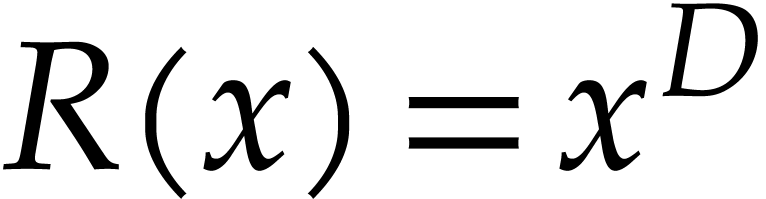

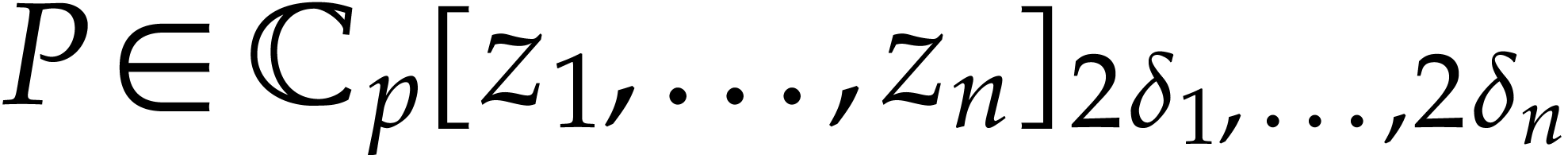

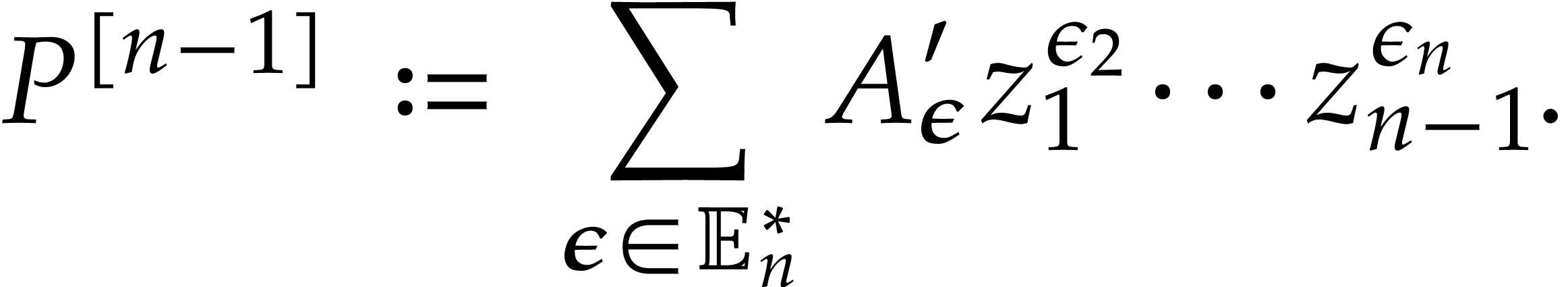

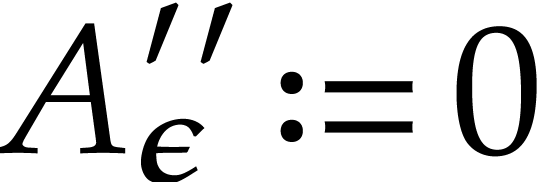

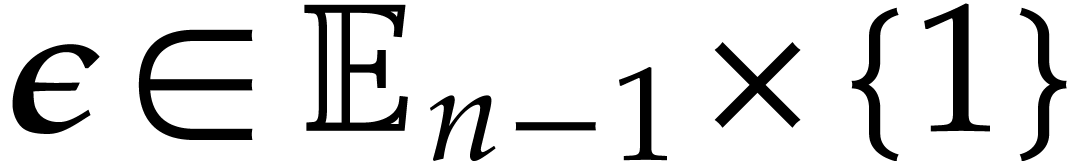

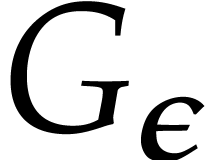

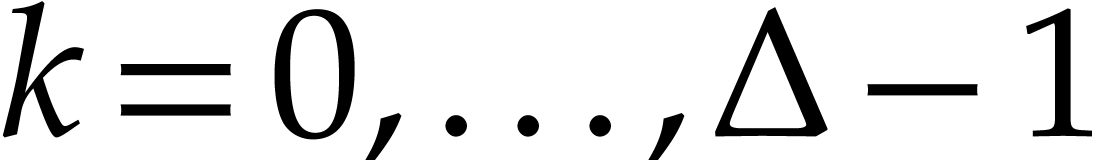

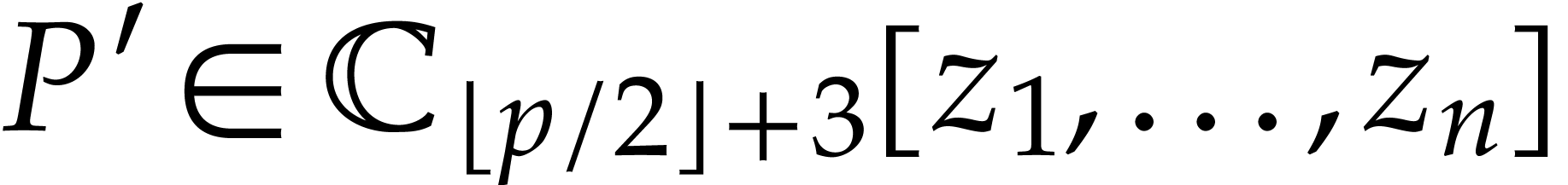

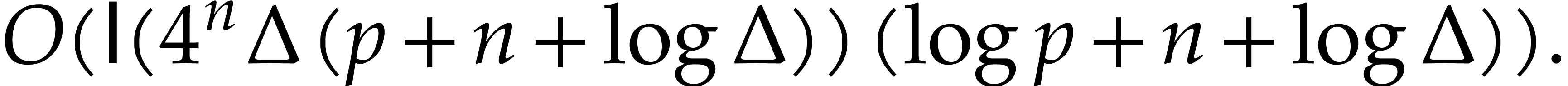

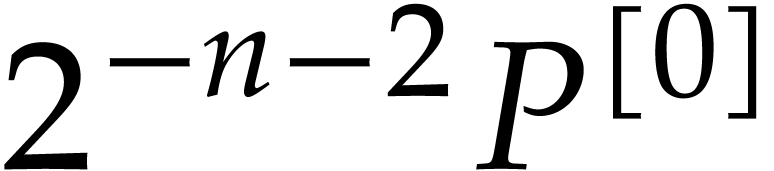

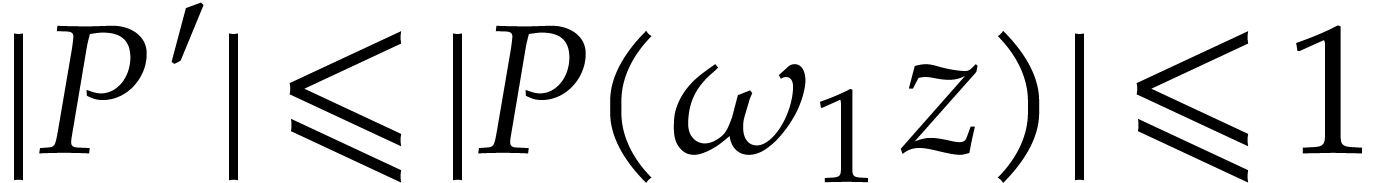

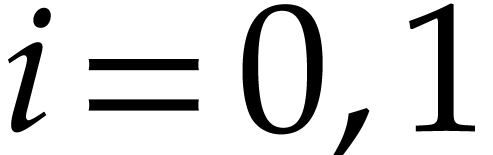

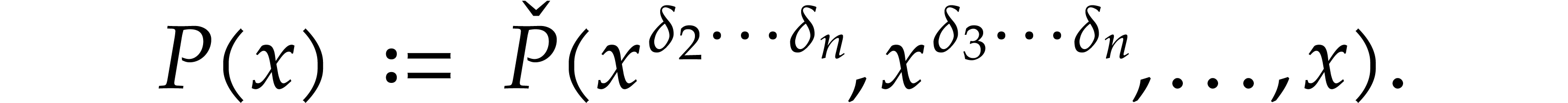

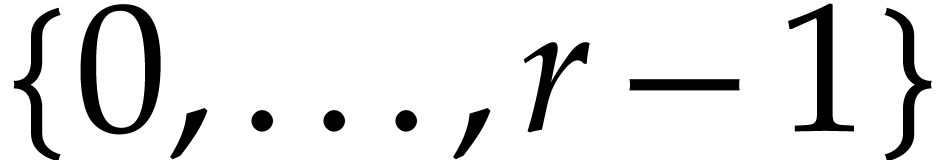

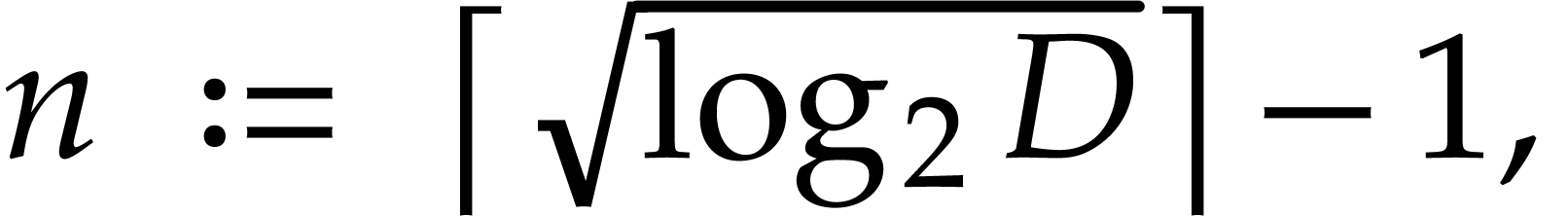

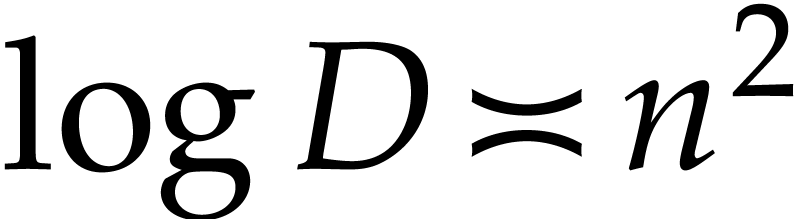

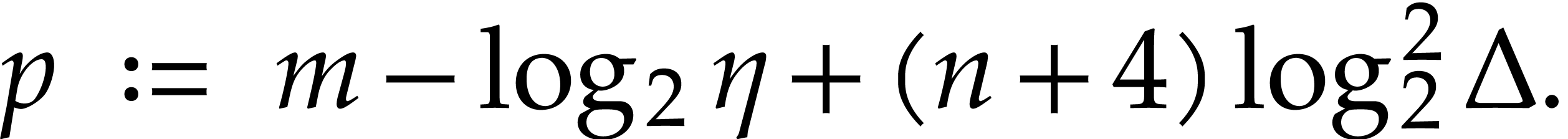

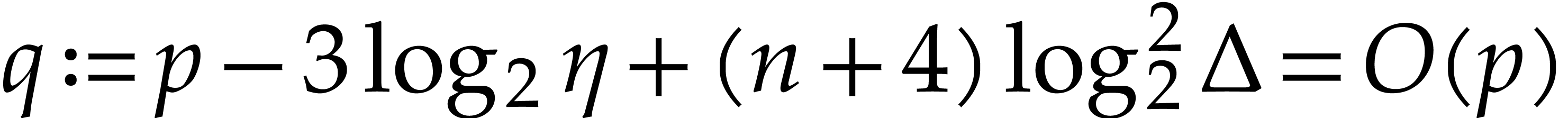

Consider  and

and  ,

where

,

where  is a positive integer. Our goal is to

compute

is a positive integer. Our goal is to

compute  . We first follow

Kedlaya and Umans [14], by transforming the problem into a

multivariate one. For some

. We first follow

Kedlaya and Umans [14], by transforming the problem into a

multivariate one. For some  and powers of two

and powers of two

with

with  and

and  , there exists a unique lift

, there exists a unique lift

such that

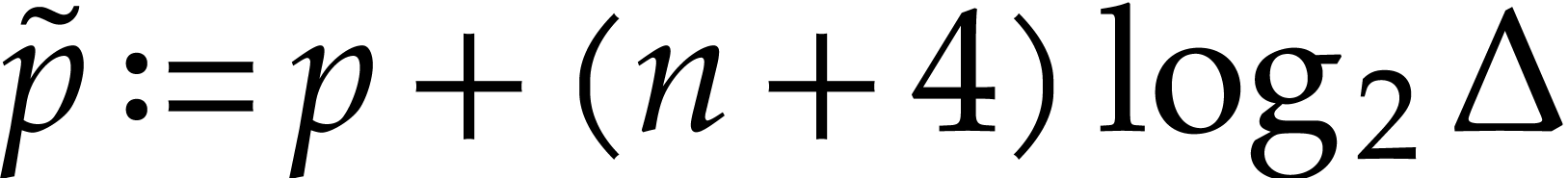

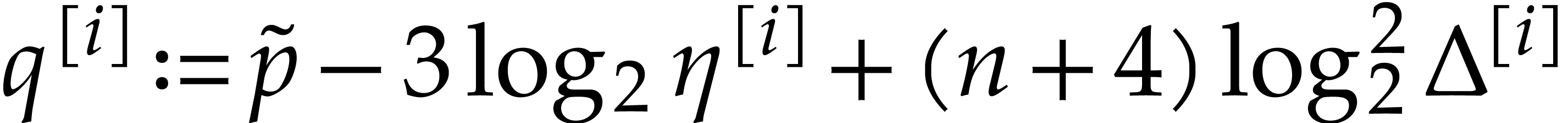

The first degree bound  will be adjusted below to

a larger value

will be adjusted below to

a larger value  that will match the setting of

the previous section. We define

that will match the setting of

the previous section. We define

so we have

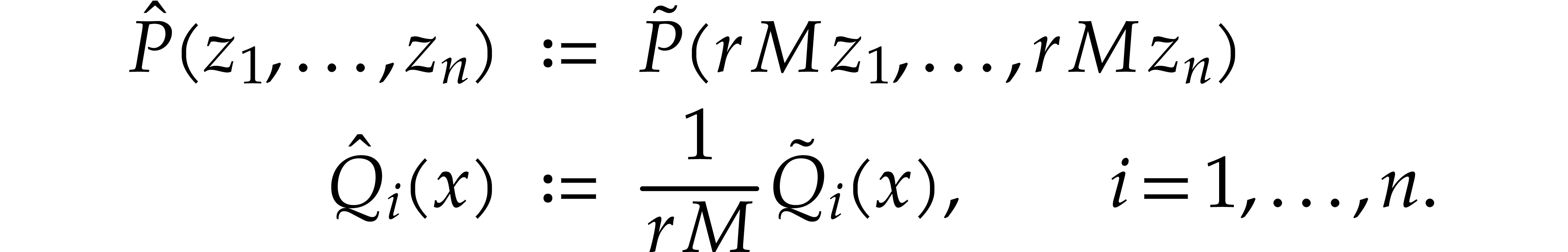

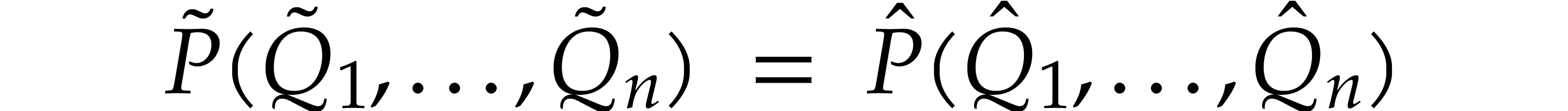

In order to compute the right-hand side of (20), we further

lift the problem into another one with integer coefficients: let  and

and  be the canonical lifts of

be the canonical lifts of

with coefficients in

with coefficients in  and

set

and

set

where  is a positive integer that will be

specified below. Note that

is a positive integer that will be

specified below. Note that  are still lifts of

are still lifts of

, so

, so

We finally rescale the polynomials, so that we can compute  using a spiroid:

using a spiroid:

Note that

and

We will evaluate

numerically using fixed point arithmetic. Setting  , we note that

, we note that

Let  be the smallest power of two satisfying

be the smallest power of two satisfying

, let

, let  , and consider the standard primitive

, and consider the standard primitive  -th root of unity

-th root of unity  .

We wish to determine

.

We wish to determine  from its values at

from its values at  . For

. For  ,

we let

,

we let

so we have

|

(21) |

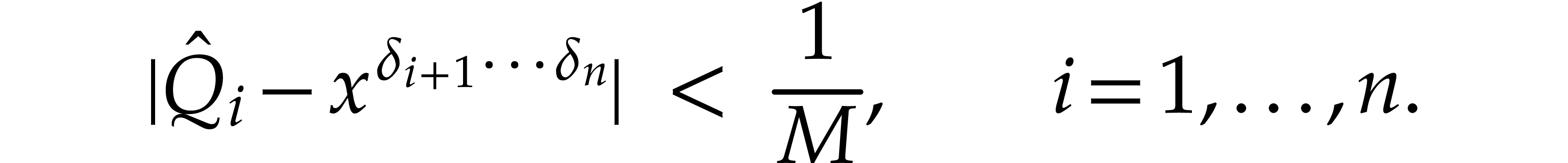

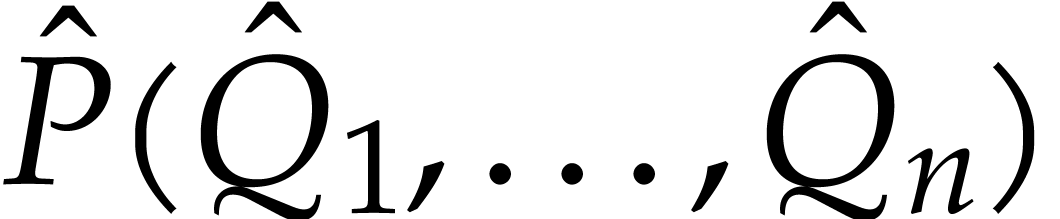

and

Choosing  sufficiently large, we will be able to

apply Algorithm 3 in order to evaluate

sufficiently large, we will be able to

apply Algorithm 3 in order to evaluate  at the spiroid

at the spiroid  . We are now

ready to prove the main theorem of this paper, from which Theorem 1 follows.

. We are now

ready to prove the main theorem of this paper, from which Theorem 1 follows.

Proof. Using binary powering, the computation of

takes time

takes time

Now we take

whence  . More precisely, we

have

. More precisely, we

have

, and

, and  . We distinguish the following cases in order to

construct the sequence

. We distinguish the following cases in order to

construct the sequence  :

:

If  then we take

then we take  minimal such that

minimal such that  , and

then

, and

then  and

and  .

Note that

.

Note that  does exist.

does exist.

Otherwise,  .

.

If  then we take

then we take  minimal such that

minimal such that  ,

and then

,

and then  and

and  .

.

Otherwise we take

.

.

In this way we achieve  and

and

|

(22) |

whence

|

(23) |

and

|

(24) |

Recall that  . Now we take

. Now we take

and

and  minimal such that

minimal such that

so, using

|

(25) |

With this choice for  , the

inequality

, the

inequality

Let  be the smallest power of two that satisfies

be the smallest power of two that satisfies

, so we have

, so we have  . We set

. We set

From

and that

|

(27) |

Since  , using Lemma 5

with

, using Lemma 5

with  , we compute a

truncation

, we compute a

truncation  of

of  with error

with error

in time

in time

Since  , Proposition 23

allows us to compute an evaluation tree for

, Proposition 23

allows us to compute an evaluation tree for  with

error

with

error  in time

in time

Following Proposition 19, this bound dominates the cost for

obtaining an approximation  of

of  with error

with error  , where

, where  , so we have

, so we have

hence

|

(30) |

thanks to Lemma 10. Via Lemma 5, we compute

such that

such that

|

(31) |

in time  , using

, using

so rounding the coefficients of  to the nearest

integers yields

to the nearest

integers yields  . Since

. Since

we compute  in time

in time

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

(using |

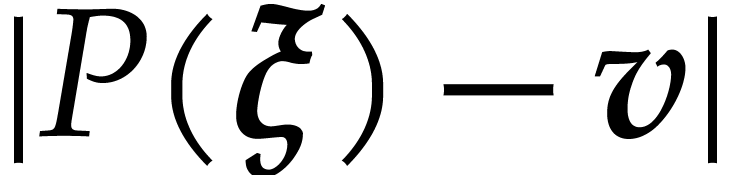

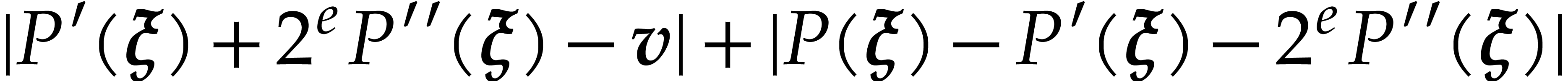

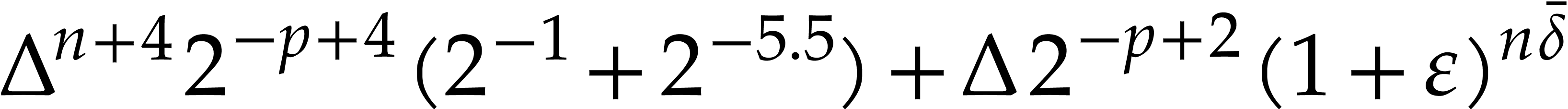

The final division of  by

by  over

over  has cost

has cost

The total cost of the method is dominated by

V. Bhargava, S. Ghosh, Z. Guo, M. Kumar, and C. Umans. Fast multivariate multipoint evaluation over all finite fields. In 2022 IEEE 63rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), pages 221–232. New York, NY, USA, 2022. IEEE.

V. Bhargava, S. Ghosh, M. Kumar, and C. K. Mohapatra. Fast, algebraic multivariate multipoint evaluation in small characteristic and applications. J. ACM, 70(6):1–46, 2023. Article No. 42.

R. P. Brent and H. T. Kung. Fast algorithms for manipulating formal power series. J. ACM, 25(4):581–595, 1978.

P. Bürgisser, M. Clausen, and M. A. Shokrollahi. Algebraic Complexity Theory, volume 315 of Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften. Springer-Verlag, 1997.

J. von zur Gathen and J. Gerhard. Modern computer algebra. Cambridge University Press, New York, 3rd edition, 2013.

D. Harvey and J. van der Hoeven. Integer

multiplication in time  .

Ann. Math., 193(2):563–617, 2021.

.

Ann. Math., 193(2):563–617, 2021.

D. Harvey, J. van der Hoeven, and G. Lecerf. Even faster integer multiplication. J. Complexity, 36:1–30, 2016.

J. van der Hoeven. The Jolly Writer. Your Guide to GNU TeXmacs. Scypress, 2020.

J. van der Hoeven and G. Lecerf. Composition modulo powers of polynomials. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, ISSAC '17, pages 445–452. New York, NY, USA, 2017. ACM.

J. van der Hoeven and G. Lecerf. Modular composition via factorization. J. Complexity, 48:36–68, 2018.

J. van der Hoeven and G. Lecerf. Fast multivariate multi-point evaluation revisited. J. Complexity, 56:101405, 2020.

J. van der Hoeven and G. Lecerf. Univariate polynomial factorization over finite fields with large extension degree. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput., 35:121–149, 2024.

E. Kaltofen and V. Shoup. Fast polynomial factorization over high algebraic extensions of finite fields. In Proceedings of the 1997 International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation, ISSAC '97, pages 184–188. New York, NY, USA, 1997. ACM.

K. S. Kedlaya and C. Umans. Fast polynomial factorization and modular composition. SIAM J. Comput., 40(6):1767–1802, 2011.

Y. Kinoshita and B. Li. Power series composition in near-linear time. In 2024 IEEE 65th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS), pages 2180–2185. IEEE, 2024.

V. Neiger, B. Salvy, É. Schost, and G. Villard. Faster modular composition. J. ACM, 71(2):1–79, 2023. Article No. 11.

M. S. Paterson and L. J. Stockmeyer. On the number of nonscalar multiplications necessary to evaluate polynomials. SIAM J. Comput., 2(1):60–66, 1973.

A. Schönhage. Asymptotically fast algorithms for the numerical muitiplication and division of polynomials with complex coefficients. In J. Calmet, editor, Computer Algebra. EUROCAM '82, European Computer Algebra Conference, Marseilles, France, April 5-7, 1982, volume 144 of Lect. Notes Comput. Sci., pages 3–15. Berlin, Heidelberg, 1982. Springer-Verlag.

V. V. Williams, Y. Xu, Z. Xu, and R. Zhou. New bounds for matrix multiplication: from alpha to omega. In D. P. Woodruff, editor, Proceedings of the 2024 Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA), pages 3792–3835. Philadelphia, PA 19104 USA, 2024. SIAM.